Prevalence of Depressive Episodes With Psychotic Features in the General Population

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study evaluated the prevalence of major depressive episodes with psychotic features in the general population and sought to determine which depressive symptoms are most frequently associated with psychotic features. METHOD: The sample was composed of 18,980 subjects aged 15–100 years who were representative of the general populations of the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. The participants were interviewed by telephone by using the Sleep-EVAL system. The questionnaire included a series of questions about depressive disorders, delusions, and hallucinations. RESULTS: Overall, 16.5% of the sample reported at least one depressive symptom at the time of the interview. Among these subjects, 12.5% had either delusions or hallucinations. More than 10% of the subjects who reported feelings of worthlessness or guilt and suicidal thoughts also had delusions. Feelings of worthlessness or guilt were also associated with high rates of hallucinations (9.7%) and combinations of hallucinations and delusions (4.5%). The current prevalence of major depressive episode with psychotic features was 0.4% (95% CI=0.35%–0.54%), and the prevalence of a current major depressive episode without psychotic features was 2.0% (95% CI=1.9%–2.1%), with higher rates in women than in men. In all, 18.5% of the subjects who fulfilled the criteria for a major depressive episode had psychotic features. Past consultations for treatment of depression were more common in depressed subjects with psychotic features than in depressed subjects with no psychotic features. CONCLUSIONS: Major depressive episodes with psychotic features are relatively frequent in the general population, affecting four of 1,000 individuals. Feelings of worthlessness or guilt can be a good indicator of the presence of psychotic features.

Depression is the most common mental disease and is the second leading cause of disability in Europe and the United States after heart diseases. Estimates of the previous-year prevalence of major depressive disorders in the general population have varied between 2.1% and 7.6%, and estimates of the previous-month prevalence have varied between 1.5% and 6%, depending on the country studied and the classification system used (DSM-III, DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, or ICD-10) (1–8). However, these studies limited their analyses to broad diagnostic categories (major depressive disorder and dysthymia) without describing specifiers of the major depressive disorder. One study found that the lifetime prevalence of psychotic symptoms in subjects who had ever met the criteria for major depression was 14% (0.6% lifetime prevalence of major depressive episode with psychotic features) (9). However, there are generally few data about the prevalence of associated psychotic features in subjects with major depressive disorders in the general population. A number of studies have reported that psychotic depression differs from nonpsychotic depression in several respects (10–13). A clinical study comparing patients with DSM-III-R major depressive disorder with psychotic features to those without psychotic features reported that the delusional patients were younger, more frequently had a past history of delusions, and more frequently had feelings of worthlessness (13). Another study did not find differences between psychotic and nonpsychotic depressed subjects in their clinical features (age at onset, duration of the episode, frequency) (14). In this study we report the prevalence of DSM-IV major depressive episodes with and without psychotic features in the general population of five Western European countries. We evaluated which depressive symptoms were more likely to be associated with psychotic features in the general population and the relative contributions of age, gender, and chronicity to the prevalence of major depressive episode with or without psychotic features.

Method

Sampling

The participants in the five countries were interviewed by telephone between 1994 and 1999 with the broader purpose of investigating sleep habits, sleep-related symptoms, and psychiatric and sleep disorders (15). The United Kingdom, with approximately 46 million inhabitants age 15 years or older, was the first country to be studied in 1994. Germany, with 66 million inhabitants age 15 years or older, was studied next in 1996; then Italy in 1997, with 46 million inhabitants 15 years or older; Portugal in 1998, with 8 million inhabitants 18 years or older; and Spain in 1999, with 38.5 million inhabitants 15 years or older. (The minimum age for Portugal was set at 18 years on the recommendation of the ethics committee for the Portuguese survey.) The study was approved by the ethical and research committee at the Canadian university where the principal investigator (M.M.O.) was located at the time of the research and by ethics committees in each of the countries where the surveys were conducted. The surveys were conducted with the help of the Teleperformance Group, a poll service company with several affiliates in Europe (British Poll Service [United Kingdom study], Teleperformance [German study], Grandi Numeri [Italian and Spanish studies], and the poll company Action [Portugal]). All surveys were conducted under the supervision of the principal investigator (M.M.O.).

The target population was all noninstitutionalized residents age 15 years or older (or 18 years or older for Portugal). The same two-stage sampling strategy was used for all five countries. In the first stage, the population was divided by geographical distribution according to the official census data for each country, and then telephone numbers were randomly drawn. In the second stage, within each sampled household a member was selected as a function of age and gender by using the Kish method (16) to maintain the representativeness of the sample and to avoid bias related to noncoverage error.

Participants had to first grant their verbal consent before proceeding with the interview. For subjects younger than 18 years of age, the verbal consent of the parents was also requested. We excluded potential participants who had insufficient fluency in the national language, who had a hearing or speech impairment, or who had an illness that made an interview infeasible.

The participation rate was 79.6% (4,972 of 6,249 eligible individuals) in the United Kingdom; 68.1% (4,115 of 6,047 eligible individuals) in Germany; 89.4% (3,970 of 4,442 eligible individuals) in Italy; 83.1% (1,858 of 2,234 eligible subjects) in Portugal; and 87.5% (4,065 of 4,648 eligible individuals) in Spain. Overall, 18,980 subjects participated in the study. The overall participation rate was 80.4%. This sample was representative of 205,890,882 inhabitants.

Instrument

The Sleep-EVAL expert system (17, 18), software developed by the principal investigator (M.M.O.) to conduct epidemiological studies in the general population and to administer questionnaires, was used to perform the interviews. The questions and possible answers were displayed on a computer screen to lay interviewers, who read them to the subjects and entered the subjects’ answers into the system.

The knowledge base of the Sleep-EVAL system comprised a standard questionnaire and diagnostic pathways covering the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (19) and DSM-IV. The questionnaire consisted of questions about sociodemographic characteristics and sleep/wake schedule, physical health queries, and questions related to sleep and mental disease symptoms and diagnoses. Questions related to mental disorders represented about two-thirds of the questionnaire instrument. Interviews typically began with general questions about demographic characteristics, followed by questions about sleeping habits. The interviews progressed to more sensitive questions regarding mental health. Questions regarding psychotic symptoms were asked near the end of the interview.

The system used the answers to select a series of plausible diagnostic hypotheses (causal reasoning process). Further questioning and deductions of the consequences of each answer allowed the system to confirm or reject these hypotheses (nonmonotonic, level-2 feature). The differential diagnosis process was based on a series of key rules allowing or prohibiting the co-occurrence of two diagnoses in accordance with the International Classification of Sleep Disorders and DSM-IV criteria. The interview ended once all diagnostic possibilities were exhausted.

The system has been tested in various contexts; in clinical psychiatry, overall agreement between the diagnoses of four psychiatrists and those of the system ranged from 0.44 (kappa) with one psychiatrist to 0.78 (kappa) with two psychiatrists (N=114 cases) (20). In another study that involved 91 forensic patients, most of the patients (60%) met the criteria for a diagnosis in the psychosis spectrum. The agreement between diagnoses obtained by the system and those given by psychiatrists was 0.44 (kappa) for specific psychotic disorders (mainly schizophrenia). Validation studies performed in sleep disorders clinics (Stanford University, University of Regensburg, and Toronto Hospital) that tested the diagnoses of the system against those of sleep specialists who used polysomnographic data gave kappas between 0.71 and 0.93 for different sleep disorders (21, 22).

The duration of the interviews ranged from 10 to 333 minutes, with an average of 40 minutes (SD=20 minutes). The longest interviews involved subjects with multiple sleep and mental disorders. Interviews were completed over two or more sessions if the duration exceeded 60 minutes.

Variables

The exploration of depression began with questions assessing whether the subject 1) was feeling sad, downcast, or depressed; 2) was feeling hopeless; and 3) had lost interest or lacked pleasure in activities formerly considered pleasant. The subjects were asked to rate these symptoms on an intensity scale (extremely, a lot, moderately, slightly, not at all, does not know) and asked whether each symptom was present most of the day and nearly every day. Subjects who answered positively to one of these symptoms were asked another series of questions that assessed 1) changes in appetite or weight; 2) insomnia or hypersomnia symptoms; 3) psychomotor agitation or retardation; 4) fatigue or loss of energy; 5) feelings of worthlessness or guilt; 6) difficulties in concentration or thinking and difficulties making decisions; and 7) suicidal ideation. These symptoms were rated by the subjects on the same intensity scale that was used for the initial symptoms, and the subjects were asked whether the symptom was present most of the day and nearly every day. The subjects also reported how long they had experienced depressive mood.

The subjects were also asked about current and past use of antidepressant medication and whether they were currently consulting a health professional for treatment of depressive mood or had ever done so.

The subjects also answered a series of questions about delusions and hallucinations (23). Each question was answered on a frequency scale (never, less than once a month, one to three times a month, one time a week, two to five times a week, six to seven times a week). To exclude subjects who may have had transient symptoms, only those subjects whose symptoms occurred at least six to seven times a week were considered to have delusions and/or hallucinations associated with depressive mood.

To conclude that a DSM-IV major depressive episode was present, all five criteria needed to be met. Therefore, subjects who met the description of a mixed episode (i.e., who had both a major depressive episode and a manic episode), those who developed depressive symptoms in relationship to the use or withdrawal of a drug or a medication, or those who developed depressive symptoms in relationship to the loss of a loved one were not considered to have a DSM-IV major depressive episode. For example, someone who said that he or she was drinking and whose depressive symptoms appeared after the beginning of the alcohol use (i.e., the subject had been drinking before the onset of depressive mood) and who said that his/her mood has changed since the use of the alcohol was not considered to have a DSM-IV major depressive episode. Similarly, a subject who reported having lost a loved one more than 2 months ago and who met all the criteria of a DSM-IV major depressive episode was classified as having a major depressive episode.

Analyses

A weighting procedure was applied to correct for disparities between the geographical, age, and gender distribution of the sample and that of the general population in each country. This procedure compensated for any potential bias from such factors as an uneven response rate across demographic groups. Results are based on weighted N values. Percentages for target variables are given with 95% confidence intervals (CI) or standard errors. Bivariate analyses were performed by using the chi-square test. The Bonferroni correction was applied to correct for multiple comparisons. Logistic regression was used to compute the odd ratios associated with a major depressive episode with or without psychotic features. Logistic regression analyses were performed by using the SUDAAN software (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, N.C.), which allows an appropriate estimate of the standard errors from stratified samples by means of a Taylor series linearization method. Reported differences were significant at the 0.05 level or less.

Results

The sample included 18,980 subjects between 15 and 100 years old. Subjects from the United Kingdom represented 26.2% of the sample; German subjects, 21.7%; Spanish subjects, 21.4%; Italian subjects, 20.9%; and Portuguese subjects, 9.8%.

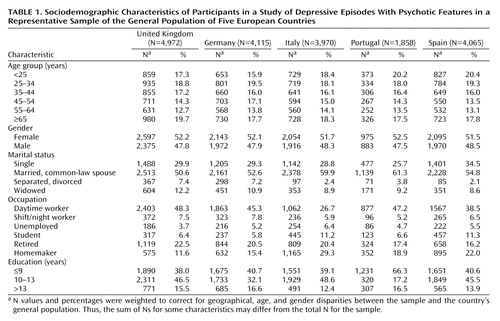

Table 1 presents the demographic distribution of the sample by country. There were no significant differences in the gender and age distribution between the countries. Italy, Portugal, and Spain had lower rates of separated or divorced participants than the United Kingdom and Germany.

Some disparities in occupation between the countries were found. The percentage of participants who were working was lower in Italy and Spain than in the United Kingdom, Germany, and Portugal because there were more homemakers and students in Italy and Spain than in the other three European countries.

The level of education was translated into years of schooling to facilitate comparisons between the countries. In the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, and Spain, basic education ends when the individual is 16 years old, while in Portugal an individual finishes basic education at age 15. Consequently, there were more participants with 9 years or less of schooling in Portugal than in the other countries.

Point Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms

At the time of the interview, 16.5% (95% CI=16.0% – 17.1%) of the subjects answered positively to one of the three basic series of questions about depressive symptoms. The most frequent depressive symptom was loss of interest and lack of pleasure in activities formerly considered pleasant (11.2%; 95% CI=10.8%–11.7%). The feeling of being down or depressed was second, with a prevalence of 7.1% (95% CI=6.8%–7.5%). Feelings of hopelessness had a prevalence of 2.4% (95% CI=2.2%–2.6%).

Depressive Symptoms and Psychotic Features

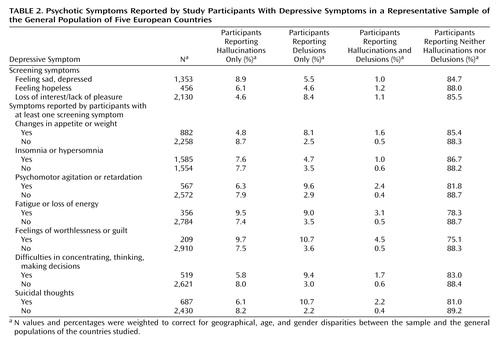

About 12.5% of the subjects with one of the three key depressive symptoms had either delusions or hallucinations. Hallucinations were reported by 7.6% of those subjects, and delusions by 4.1%. A combination of hallucinations and delusions was reported by 0.8% of subjects with a depressive mood (Table 2). Most of the reported hallucinations were auditory (96.7%).

Subjects reporting at least one of the three key symptoms were asked about other depressive symptoms. As Table 2 shows, subjects reporting feelings of worthlessness or guilt and suicidal thoughts had the highest likelihood of reporting delusions (more than 10%). Subjects who reported fatigue or loss of energy and feelings of worthlessness or guilt had the highest likelihood of reporting hallucinations and a combination of hallucinations and delusions (Table 2).

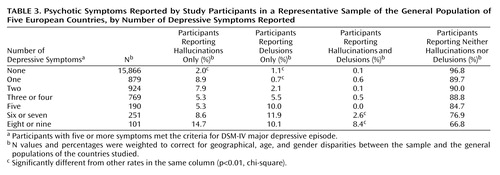

The proportion of subjects reporting hallucinations and/or delusions increased with the number of depressive symptoms, reaching 33.2% in those with eight or nine depressive symptoms (Table 3). The proportion of subjects having hallucinations was considerably higher among those who reported at least one depressive symptom; 2.0% of subjects without depressive symptoms reported hallucinations, compared with 5.3%–14.7% of subjects with at least one depressive symptom. The proportion of subjects with delusions was considerably higher among those who reported two or more depressive symptoms (2.1%–11.9%) than among those without depressive symptoms (1.1%). The rate of co-occurrence of hallucinations and delusions dramatically increased when six depressive symptoms or more were present; the rate jumped from 0.1% in nondepressive subjects to between 2.6% and 8.4% in subjects with at least six symptoms (Table 3).

DSM-IV Major Depressive Episode and Psychotic Features

Overall, 454 subjects met all the criteria of a DSM-IV major depressive episode. Eighty-eight subjects with at least five of the nine depressive symptoms were eliminated in the differential diagnosis process. Overall, 10.6% of subjects with a major depressive episode had only delusions, 6.8% had only hallucinations, and 1.2% had both delusions and hallucinations. Therefore, subjects with a major depressive episode were nine times more likely to have delusions than subjects without a major depressive episode (odds ratio=8.9, 95% CI=6.4–12.3). The likelihood of having hallucinations was nearly three times higher in subjects with a major depressive episode than in those without (odds ratio=2.8, 95% CI=1.9–4.1). Finally, the likelihood of having both hallucinations and delusions was nine times higher in subjects with a major depressive episode than in those without (odds ratio=8.7, 95% CI=3.4–22.1).

The point prevalence of a DSM-IV major depressive episode with or without psychotic features was 2.4% (95% CI=2.2%–2.6%). A major depressive episode with psychotic features had a prevalence of 0.4% (95% CI=0.35%–0.54%), and a major depressive episode without psychotic features had a prevalence of 2.0% (95% CI=1.9%–2.1%).

There was no significant difference between the countries for the point prevalence of a DSM-IV major depressive episode with psychotic features. The point prevalences were 0.5% (95% CI=0.3%–0.7%) in the United Kingdom, 0.4% (95% CI=0.2%–0.6%) in Germany, 0.2% (95% CI=0.1%–0.3%) in Italy, 0.5% (95% CI=0.2%–0.8%) in Portugal, and 0.2% (95% CI=0.1%–0.3%) in Spain.

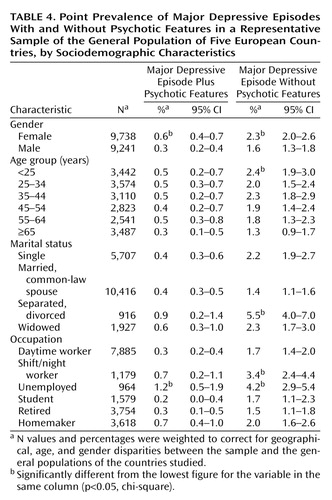

Major depressive episodes with or without psychotic features both were more prevalent in women than in men. A major depressive episode without psychotic features was less prevalent in subjects age 65 years or older (Table 4). Divorced or separated individuals were more likely to have a major depressive episode without psychotic features than were married subjects (Table 4). Shift or night workers and unemployed subjects were more likely to have a major depressive episode with or without psychotic features than were daytime workers, students, or retired individuals (Table 4). More specifically, unemployed men were six times more likely to have a major depressive episode with psychotic features (odds ratio=5.8, p<0.0001) and two times more likely to have a major depressive episode without psychotic features (odds ratio=2.2, p<0.05) than daytime workers. Male shift or night workers were more likely to have a major depressive episode without psychotic features (odds ratio=2.0, p<0.01) than were male daytime workers.

Among women, unemployed participants were three times more likely (odds ratio=2.9, p<0.01) to have a major depressive episode with psychotic features and two times more likely (odds ratio=2.5, p<0.001) to have a major depressive episode without psychotic features than those who were employed. Shift or night workers were also three times more likely (odds ratio=2.7, p<0.05) to have a major depressive episode with psychotic features and two times more likely (odds ratio=2.1, p<0.01) to have a major depressive episode without psychotic features than were daytime workers.

It is interesting to note that the frequency of some depressive symptoms changed with the occupation status. For example, more than 40% of depressed male shift or night workers reported changes in appetite or weight; this proportion was at least two times higher than in other occupation categories. This was not the case with depressed women. Suicidal thoughts were at least two times more frequent in unemployed depressed men (25%), followed by depressed male shift or night workers (21%), compared with other occupation categories. This pattern was also observed in unemployed women.

Finally, subjects with a major depressive episode with psychotic features were twice as likely to have consulted a health professional for treatment of depression in the past than were subjects with a major depressive episode without psychotic features (28.0% versus 18.3%) (χ2=4.03, df=1, p<0.05). The duration of the current episode was also longer in subjects with a major depressive episode with psychotic features than in those without psychotic features, but the difference was not significant (mean duration in months=20.0 versus 15.6) (F=2.35, df=1, 331, p=0.13).

Discussion

This study investigated the associations between depressive symptoms and psychotic features in a sample of 18,980 subjects in five European countries. The current prevalence of DSM-IV major depressive episode was set at 2.4% in this sample. About 19% of the subjects with a major depressive episode had psychotic features, yielding a prevalence of major depressive episode with psychotic features of 0.4% in this sample. Thus, psychotic major depression is a relatively common disorder, affecting four of 1,000 individuals.

In this study, the prevalence of DSM-IV major depressive episodes in individuals age 15 years and older (2.4%) is comparable to the 1-month prevalence reported in the ECA study (2.2%). It is, however, lower than the 1-month prevalence of 4.9% reported for subjects age 15–54 years in the National Comorbidity Survey (2). The National Comorbidity Survey obtained a 2.1% prevalence of a pure episode of major depression (i.e., without anxiety disorder, substance abuse or dependence, manic episode, or nonaffective psychosis). Our 2.4% prevalence of major depressive episode already excluded subjects with substance abuse or dependence, bipolar disorder, and nonaffective psychosis; if we removed subjects with anxiety disorder, we would obtain a prevalence of 1.9% of pure major depressive episode in the 15–54-year-old subjects.

There are few epidemiological data to compare with our study findings. A study by Johnson et al. (9), published more than 10 years ago, is to our knowledge the only study that can be compared to ours. Johnson et al. found that 14% of subjects with a lifetime diagnosis of major depression had psychotic features. We found that 19% of subjects with a major depressive episode also had psychotic features. Johnson et al. found a lifetime prevalence of major depression with psychotic features of 0.6%; we found a 0.4% point prevalence. They reported an increased risk of relapse in those subjects. In our study, we found an increased probability of past consultations for treatment of depression in that group of subjects.

We were surprised to find that although the severity of depression affects the likelihood of psychotic features, psychotic features were reported by a considerable number of subjects with a mild or moderate major depressive episode and by subjects who did not have enough depressive symptoms to fulfill the criteria for a major depressive disorder. As many as 10% of subjects with two depressive symptoms (with or without a diagnosis of major depressive episode) had psychotic features. This association cannot be fully explained by the presence of a bipolar disorder or another psychotic disorder, although these two disorders accounted for 34% of the association. Several other mental and neurological disorders were associated with psychotic features in subjects who had depressive symptoms but did not meet all the criteria for a major depressive episode. The other disorders included obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and panic disorder. Abuse of alcohol was also frequent. In nondepressed subjects who had psychotic features, an identifiable mental or neurological disorder was found for at least 60% of subjects.

When examining individual depressive symptoms, we found that subjects who reported feelings of worthlessness or guilt were the most likely to have psychotic features, confirming the results in a recent clinical study (13). However, the severity of this symptom was not related to the presence of psychotic features. Reports of feelings of guilt may be a useful cue to delve more deeply into the presence of psychotic features. We also found that subjects with a major depressive episode with psychotic features were more likely to have consulted professionals in the past for treatment of depression, suggesting a possible recurrence of the disorder. They had also a longer duration of the major depressive episode than the subjects without psychotic features. This finding supports those of clinical studies in which patients with a major depressive episode with psychotic features were more likely to have recurrent depressive episodes and to have episodes of longer duration (10–13). These data suggest that the duration of episode may increase the risk of developing delusions, perhaps through a biologically based process. However, we did not find that psychotic features were associated with younger age, as suggested by another study (13).

Our study is not without shortcomings. First, it was based on interviews with a noninstitutionalized general population. It is likely that depressive individuals with significant disabilities were not part of the study because they were hospitalized or too ill to complete the interview or because they simply refused to participate. Therefore, the major depressive episode prevalences presented in this paper were conservative estimates. Furthermore, the subjects could have underreported hallucinations and delusions because they were reluctant to speak about symptoms that might be considered shameful or might indicate they were mentally disturbed, although respondents in telephone interviews have felt less embarrassed about being truthful than respondents in face-to-face interviews (24). It is likely also that many individuals with hallucinations or delusions were unaware of their problem and failed to report them.

In conclusion, our study highlights the extent of depression with psychotic features. The findings have implications for diagnosis and treatment. Contrary to a common belief, depression with psychotic features is not associated with severity, raising the possibility that many such patients may be seen by general practitioners and may be inadequately treated.

|

|

|

|

Received Aug. 21, 2001; revision received May 30, 2002; accepted June 25, 2002. From the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, School of Medicine, Stanford University. Address reprint requests to Dr. Ohayon, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, School of Medicine, Stanford University, Stanford Sleep Epidemiology Research Center, 401 Quarry Rd., Suite 3301, Stanford, CA 94305; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by the Fond de la Recherche en Santé du Quebec (grant 971067) and by an unrestricted educational grant from the Sanofi-Synthelabo Group (Dr. Ohayon) and in part by NIMH grant MH-50604 (Dr. Schatzberg).

1. Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke JD Jr, Rae DS, Myers JK, Kramer M, Robins LN, George LK, Karno M, Locke BZ: One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States: based on five Epidemiologic Catchment Area sites. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:977-986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Blazer DG, Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz MS: The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:979-986Link, Google Scholar

3. Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, Faravelli C, Greenwald S, Hwu HG, Joyce PR, Karam EG, Lee CK, Lellouch J, Lepine JP, Newman SC, Rubio-Stipec M, Wells JE, Wickramaratne PJ, Wittchen H, Yeh EK: Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. JAMA 1996; 276:293-299Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Bebbington PE, Hurry J, Tennant C: The Camberwell Community Survey: a summary of results. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1991; 26:195-201Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Meltzer H, Gill B, Petticrew M, Hinds K: The Prevalence of Psychiatric Morbidity Among Adults Living in Private Households: OPCS Surveys of Psychiatric Morbidity in Great Britain Report 1. London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1995Google Scholar

6. Ohayon MM, Priest RG, Guilleminault C, Caulet M: The prevalence of depressive disorders in the United Kingdom. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 45:300-307Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Narrow WE, Rae DS, Moscicki EK, Locke BZ, Regier DA: Depression among Cuban Americans: the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1990; 25:260-268Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Newman SC, Bland RC: Life events and the 1-year prevalence of major depressive episode, generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder in a community sample. Compr Psychiatry 1994; 35:76-82Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Johnson J, Horwath E, Weissman MM: The validity of major depression with psychotic features based on a community study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:1075-1081Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Schatzberg AF, Rothschild AJ: Psychotic (delusional) major depression: should it be included as a distinct syndrome in DSM-IV? Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:733-745Link, Google Scholar

11. Schatzberg AF, Rothschild AJ: Serotonin activity in psychotic (delusional) major depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1992; 53(Oct suppl):52-55Google Scholar

12. Coryell W, Leon A, Winokur G, Endicott J, Keller M, Akiskal H, Solomon D: Importance of psychotic features to long-term course in major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:483-489Link, Google Scholar

13. Thakur M, Hays J, Ranga K, Krishnan R: Clinical, demographic and social characteristics of psychotic depression. Psychiatry Res 1999; 86:99-106Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Serretti A, Lattuada E, Cusin C, Gasperini M, Smeraldi E: Clinical and demographic features of psychotic and nonpsychotic depression. Compr Psychiatry 1999; 40:358-362Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Ohayon MM, Guilleminault C, Paiva T, Priest RG, Rapoport DM, Sagales T, Smirne S, Zulley J: An international study on sleep disorders in the general population: methodological aspects of the Sleep-EVAL system. Sleep 1997; 20:1086-1092Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Kish L: Survey Sampling. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1965Google Scholar

17. Ohayon M: Knowledge-Based System Sleep-EVAL: Decisional Trees and Questionnaires. Ottawa, National Library of Canada, 1995Google Scholar

18. Ohayon M: Improving decision-making processes with the fuzzy logic approach in the epidemiology of sleep disorders. J Psychosom Res 1999; 47:297-311Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. ICSD Diagnostic Classification Steering Committee: International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual (ICSD). Rochester, Minn, American Sleep Disorders Association, 1990Google Scholar

20. Ohayon M: Validation of expert systems: examples and considerations. Medinfo 1995; 8:1071-1075Medline, Google Scholar

21. Ohayon MM, Guilleminault C, Zulley J, Palombini L, Raab H: Validation of the Sleep-EVAL system against clinical assessments of sleep disorders and polysomnographic data. Sleep 1999; 22:925-930Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Hosn R, Shapiro CM, Ohayon MM: Diagnostic concordance between sleep specialists and the Sleep-EVAL system in routine clinical evaluations (abstract). J Sleep Res 2000; 9:86Google Scholar

23. Ohayon MM: Prevalence of hallucinations and their pathological associations in the general population. Psychiatry Res 2000; 97:153-164Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Aneshensel CS, Frerichs RR, Clark VA, Yokopenic PA: Measuring depression in a community, a comparison of telephone and personal interviews. Public Opinion Q 1982; 46:110-121Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar