Effect of Memantine on Cue-Induced Alcohol Craving in Recovering Alcohol-Dependent Patients

Abstract

Objective: Ethanol blocks N -methyl- d -aspartic acid (NMDA) glutamate receptors. Increased NMDA receptor function may contribute to motivational disturbances that contribute to alcoholism. The authors assessed whether the NMDA receptor antagonist memantine reduces cue-induced alcohol craving and produces ethanol-like subjective effects. Method: Thirty-eight alcohol-dependent inpatients participated in three daylong testing sessions in a randomized order under double-blind conditions. On each test day, subjects received 20 mg of memantine, 40 mg of memantine, or placebo, and subjective responses to treatment were assessed. The level of alcohol craving was assessed before and after exposure to an alcohol cue. Results: Memantine did not stimulate alcohol craving before exposure to an alcohol cue, and it attenuated alcohol cue-induced craving in a dose-related fashion. It produced dose-related ethanol-like effects without adverse cognitive or behavioral effects. Conclusions: These data support further exploration of whether well-tolerated NMDA receptor antagonists might have a role in the treatment of alcoholism.

Antagonists of N -methyl- d -aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptors may have a role in the pharmacotherapy of alcoholism (1 – 3) . Blockade of NMDA receptors by ethanol contributes to ethanol’s effects in animal and human subjects (1) . Groups at risk of heavy drinking exhibit decreased dysphoric mood responses to NMDA receptor antagonists (1 , 4) . Enhanced NMDA receptor function in alcohol dependence also may contribute to disturbances in circuitry underlying reward-related motivational states (1 , 3 , 5) . We hypothesized that NMDA receptor antagonists might reduce alcohol craving by attenuating disturbances in reward-related motivational processes and by providing an intoxication cue that reduces urges to consume ethanol (1 , 4 , 5) .

Memantine is a well-tolerated NMDA receptor antagonist (2) . In animals, administration of memantine has been shown to significantly reduce increased alcohol consumption following alcohol deprivation (3) . In human subjects, memantine has been reported to reduce the level of alcohol craving preceding alcohol consumption in the laboratory without attenuating the rise in craving that follows consumption (2) . However, there have been no published reports on the effects of memantine in the treatment of alcoholism.

The pharmacologic modulation of alcohol cue-induced alcohol craving may be predictive of the effects medication will have on drinking during treatment of alcohol dependence (6) . In this study, we explore the dose-related subjective effects and modulation of cue-induced alcohol craving produced by single doses of memantine in recovering alcohol-dependent patients.

Method

This study was approved by the internal review board of the St. Petersburg Pavlov State Medical University (St. Petersburg, Russia) and the Human Subjects Subcommittee of the VA Connecticut Health Care System (West Haven, Conn.). Patients gave written informed consent before entering the study.

Participants

Thirty-eight male inpatients (mean age, 39.2 years [SD=9.0]) who met ICD-10 criteria for alcohol dependence on the basis of clinical interview and DSM-IV criteria according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders—Patient Edition (7) were recruited from the St. Petersburg Regional Center of Addictions (St. Petersburg, Russia). Participants had been alcohol dependent for a mean of 11.2 years (SD=6.5). Eleven participants (29%) had a first-degree relative who met family history diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence (8) . Exclusionary criteria included current psychoactive medications and being at risk for untoward side effects from memantine (i.e., liver enzyme levels more than three times higher than normal levels and evidence of active renal, hepatic, or cardiac disease on the basis of history, ECG, or other laboratory findings). Patients had been sober for a mean of 22.1 days (range=5–54 days; SD=13.4) and had not taken any psychoactive medications for at least 1 week before entering the study. Thirty-six participants (95%) smoked cigarettes and met criteria for nicotine dependence; participants had ad libitum access to cigarettes until the initiation of the test. Thirty-one participants (85%) identified vodka as their drink of choice, five (8%) preferred wine, and two (5%) chose beer.

Testing

Each subject participated in three daylong testing sessions separated by at least 3 three days. Each test day began at approximately 8:00 a.m. A number of clinical assessments were performed 60 minutes before the administration of study drug and repeated 180 minutes and 360 minutes afterward. At 240 minutes after drug administration—and 2 minutes after an assessment of level of craving—subjects were exposed to an alcohol cue with their drink of choice. They were instructed to smell and handle their drink, but not to consume it, and then to hold it for 3 minutes. At approximately 255 minutes, level of craving was once again assessed. At 390 minutes after drug administration, a relaxation script was reviewed with patients and a general clinical briefing was conducted.

On each test day, a single dose of 20 or 40 mg of memantine or placebo (Merz Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Frankfurt, Germany) was administered in a randomized order, under double-blind conditions. No order effects were observed in this study.

Dependent Measures

The Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale (9) includes seven items that assess stimulant effects and seven that assess sedative effects. Visual analogue scales (0–100 mm) were used to assess similarity to ethanol, euphoria, and alcohol craving (10) . Intensity of alcohol effects was assessed with the “number of drinks scale”—the estimated number of standard ethanol drinks (10 g ethanol) needed to produce a given subjective state. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) was administered to evaluate a broad range of clinical responses (11 , 12) ; in this report we highlight two BPRS subscales, one measuring positive symptoms (psychosis) and the other measuring negative symptoms associated with schizophrenia (11) . Two cognitive tests were used: a verbal fluency test (13) and the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (14) . All instruments were administered 1 hour before and 3 and 6 hours after drug administration, except the cognitive tests; the verbal fluency test was administered 1 hour before and 3 hours after drug administration, and the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test was administered only at 3 hours.

At the end of each test day, subjects were debriefed about any craving that emerged over the course of the testing.

Data Analysis

Each outcome was tested for normality using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test statistics and normal probability plots. The verbal fluency test and the immediate and delayed recall subtests of the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test were approximately normal; however, most other outcomes were positively skewed. Non-normal outcomes were analyzed using the ANOVA-type statistic (ATS) nonparametric approach for repeated-measures data by Brunner (15) , and linear mixed models were used for normal outcomes. In these models, each outcome represented the dependent variable, and drug group (20 mg memantine, 40 mg memantine, and placebo) and time were included as within-subject explanatory factors. Subject was used as the clustering factor—that is, observations on the dependent variables were assumed to be correlated within subjects, and these correlations were accounted for in the repeated-measures analyses. Covariates considered in the models included age, family history of alcoholism, number of years dependent on alcohol, drinking pattern (binge or continuous), and history of concussion. The covariates were not significant and were dropped for parsimony, except family history, which contributed significantly to the model for craving visual analogue scale. All results were considered statistically significant at p<0.05 after Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons within but not across hypotheses. Data analyses were conducted with SAS, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, N.C.).

Results

Ethanol-Like Effects

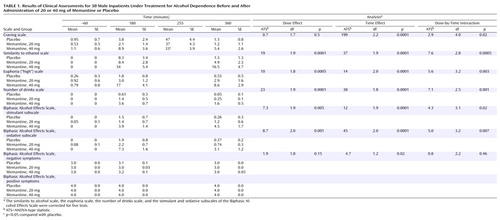

Memantine produced modest but significant dose-related ethanol-like effects, as indicated by the visual analogue scale measuring similarity to ethanol, the number of drinks scale, the visual analogue scale measuring euphoria, and the stimulant and sedative subscales of the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale ( Table 1 ).

Alcohol Craving

Memantine influenced the extent to which exposure to alcohol cues stimulated craving for alcohol, as measured by the visual analogue scale for craving ( Table 1 ). The presence of a family history of alcohol dependence was associated with higher levels of craving (family history main effect: ATS=4.0, df=1.0, p=0.05), but this history did not moderate the effects of memantine (memantine-by-family history interaction: ATS=0.47, df=1.7, n.s.). Memantine did not stimulate craving for alcohol significantly, and it reduced the cue-induced craving for alcohol. In a direct comparison of the levels of craving before and after cue exposure, the 40 mg memantine dose significantly reduced craving compared with the other two conditions (40 mg memantine versus placebo: t=3.2, df=36, p=0.008; 40 mg memantine versus 20 mg memantine: t=2.9, df=36, p=0.02).

Cognitive, Behavioral, and Other Outcomes

No significant group differences were observed in the verbal fluency test or the immediate and delayed recall subtests of the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test, and memantine did not otherwise impair cognition or affect behavior. No clinically significant adverse events occurred in association with this study.

Discussion

We found that memantine, an NMDA receptor antagonist, reduced alcohol cue-induced craving without stimulating craving for alcohol despite producing ethanol-like subjective effects. This anticraving effect is consistent with previous preclinical (3) and clinical (2) studies. The reduction in alcohol craving observed in this study was modest. Additional research will be needed to determine whether memantine is effective as a pharmacotherapy for treatment of alcohol dependence and whether chronic administration produces tolerance to its ethanol-like or therapeutic effects.

Our study design imposed some limitations on the interpretation of the findings. Our subjects were predominantly male smokers, and we did not assess levels of current or past smoking, so we were unable to explore effects of gender, smoking, or nicotine withdrawal. Assessing the impact of smoking in this study might have been interesting because memantine blocks α 7 subunit-containing nicotinic receptors in addition to NMDA receptors (16) .

The absence of memantine-stimulated alcohol craving in the presence of ethanol-like effects is consistent with the hypothesis that NMDA receptor antagonist effects produce negative feedback on drinking (4) . Alternatively, NMDA antagonists may modulate the function of circuitry underlying reward or motivation to produce the therapeutic effects on craving observed in this study (1) . The absence of negative effects on cognitive test performance and BPRS score is encouraging with respect to the safety of further exploring the efficacy of memantine in preventing or attenuating relapse to alcohol use in recovering alcohol-dependent patients.

1. Krystal JH, Petrakis IL, Mason G, D’Souza DC: NMDA glutamate receptors and alcoholism: reward, dependence, treatment, and vulnerability. Pharmacol Ther 2003; 99:79–94Google Scholar

2. Bisaga A, Evans SM: Acute effects of memantine in combination with alcohol in moderate drinkers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004; 172:16–24Google Scholar

3. Holter SM, Danysz W, Spanagel R: Evidence for alcohol anti-craving properties of memantine. Eur J Pharmacol 1996; 314:R1–R2Google Scholar

4. Krystal JH, Petrakis IL, Trevisan L, D’Souza DC: NMDA receptor antagonism and the ethanol intoxication signal: from alcoholism risk to pharmacotherapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003; 1003:176–184Google Scholar

5. Krystal JH, D’Souza DC, Gallinat J, Jacobsen L, Driesen N, Petrakis IL, Heinz A, Pearlson G: Neurobiological hypotheses for the etiology and maintenance of alcohol and substance abuse by individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia. Neurotox Res 2006 (in press)Google Scholar

6. Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Hutchison KE, Swift RM, Mueller TI, Colby SM, Brown RA, Gulliver SB, Gordon A, Abrams DB: Naltrexone’s effect on cue-elicited craving among alcoholics in treatment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1999; 23:1386–1394Google Scholar

7. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P), version 2. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1996Google Scholar

8. Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Winokur G: The family history method using diagnostic criteria: reliability and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1977; 34:1229–1235Google Scholar

9. Martin CS, Earleywine M, Musty RE, Perrine MW, Swift RM: Development and validation of the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1993; 17:140–146Google Scholar

10. Krystal JH, Petrakis IL, Webb E, Cooney NL, Karper LP, Namanworth S, Stetson P, Trevisan LA, Charney DS: Dose-related ethanol-like effects of the NMDA antagonist, ketamine, in recently detoxified alcoholics. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:354–360Google Scholar

11. Krystal JH, Petrakis IL, Limoncelli D, Webb E, Gueorguieva R, D’Souza DC, Boutros NN, Trevisan L, Charney DS: Altered NMDA glutamate receptor antagonist response in recovering ethanol-dependent patients. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003; 28:2020–2028Google Scholar

12. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep 1962; 10:799–812Google Scholar

13. Borkowski JG, Benton AL, Spreen O: Word fluency and brain damage. Neuropsychologia 1967; 5:135–140Google Scholar

14. Brandt J: The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test: development of a new memory test with six equivalent forms. Clin Neuropsychol 1991; 5:125–142Google Scholar

15. Brunner E, Domhof S, Langer F: Nonparametric Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Factorial Experiments. New York, Wiley, 2002Google Scholar

16. Aracava Y, Pereira EFR, Maelicke A, Albuquerque EX: Memantine blocks alpha-7* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors more potently than N -methyl- d -aspartate receptors in rat hippocampal neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2005; 312:1195–1205 Google Scholar