What Happens to “Bad” Girls? A Review of the Adult Outcomes of Antisocial Adolescent Girls

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this article is to review critically the data on the adult outcomes of adolescent girls with antisocial behavior. METHOD: Five literature databases were searched for studies on the adult outcomes of girls with either conduct disorder or delinquency. RESULTS: Twenty studies met the inclusion criteria. As adults, antisocial girls manifested increased mortality rates, a 10- to 40-fold increase in the rate of criminality, substantial rates of psychiatric morbidity, dysfunctional and often violent relationships, and high rates of multiple service utilization. Possible explanations for these findings include a pervasive biological or psychological deficit or baseline heterogeneity in the population of antisocial girls. CONCLUSIONS: This review establishes that female adolescent antisocial behavior has important long-term individual and societal consequences. At present, there are insufficient data to enable us to prevent these outcomes or treat them if they occur. Future research should include cross-sectional studies detailing the phenomenology of female antisocial behavior and longitudinal investigations that not only track development into adulthood but also explore the role of potential modifiying variables such as prefrontal lobe dysfunction and psychiatric comorbidity. (Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:862–870)

Jennifer is a 16-year-old girl who was brought to the emergency room for suicidal ideation. During an argument with her mother about telephone privileges, Jennifer grabbed a knife and threatened to kill her mother and herself. In the emergency room, she reported depressed mood “when I'm grounded and stuck in the house.” She denied true suicidality, stating, “I just figured that would get her to let me use the phone.” Jennifer also denied any homicidal intent, although on occasion she has hit her mother hard enough to leave bruises. She received an outpatient psychiatric evaluation a year ago but refused to return for treatment. Other problems include a history of truancy since age 13, running away, and several arrests for shoplifting and fighting. She is currently on house arrest for assaulting another girl.

What happens to girls like Jennifer as they mature into women? Do they continue their antisocial activities? Do they develop significant psychiatric morbidity? How do they behave as partners, parents, and workers? These questions have been extensively studied with respect to males (1–5) but not females. This curious omission is due to long-standing beliefs that female adolescent antisocial behavior is rare, primarily sexual in nature, and associated with a benign course in adulthood (6–11). For example, in 1968, J. Cowie (a leading researcher in the field of delinquency) wrote, “In the first place, the delinquent girl is much less frequent than her male counterpart, and.she is less interesting. Her offenses take predominantly the form of sexual misbehavior, of a kind to call for care and protection rather than punishmentDelinquency in the male at an equivalent age is very much more varied, dangerous and dramatic” (12).

In the last decade, however, reports in both the scientific literature and the lay press have challenged these notions (13–18). In the first portion of this article, I briefly present evidence that antisocial behavior among adolescent girls is neither rare or restricted to premarital sexual activity. I then review all the studies that provide data on the adult outcomes of these girls. In the last section of the article, I offer interpretations of these data, concluding with suggestions for the focus of future research.

ISSUES IN THE STUDY OF FEMALE ANTISOCIAL BEHAVIOR

Conduct Disorder and Delinquency: Similarities and Differences

We find data on antisocial girls in the psychiatric literature on conduct disorder and the juvenile justice literature on delinquent girls. The diagnosis of conduct disorder, which was not formalized until 1978, specifies a clustering of antisocial behaviors that persists for at least 6 months (DSM-IV). Before 1978, adolescents with antisocial behavior were categorized as having a runaway reaction, group delinquency reaction, or unsocialized aggressive reaction (DSM-II).

A girl adjudicated as delinquent has committed either a status or a criminal offense, all of which are behaviors included in the conduct disorder criteria, although girls with conduct disorder are often not classified as delinquent because they have not been caught. Many delinquent girls are arrested for both types of offenses, but the behaviors result in different consequences. Status offenses (e.g., running away) are unique to juveniles and are regarded as indications for legal supervision. Criminal offenses (e.g., assault) are behaviors that are considered illegal in any age group, but the penalties for juveniles are less severe. A girl can be adjudicated as delinquent for just one act, but most incarcerated girls meet the criteria for conduct disorder (19). In the juvenile justice research literature, girls may also be classified as delinquent on the basis of their scores on delinquency self-report inventories.

Is Antisocial Behavior Among Girls Rare?

Neither conduct disorder nor delinquency is rare among girls. One review (20) reported that conduct disorder is the second most common diagnosis given to adolescent girls, and another investigation (21) revealed that 8% of 17-year-old girls met the criteria for the disorder. A large epidemiologic study of 15-year-olds (22) reported that 7.5%–9.5% of the girls met the criteria for conduct disorder, compared to 8.6%–12.2% of the boys.

Estimating the prevalence of female delinquency is more complicated. The validity of arrest data, which led to the conclusion that female delinquency was uncommon, has been questioned on the basis of gender bias in the justice system (23–26). This bias resulted in reluctance to arrest girls, coupled with a tendency toward psychiatric referrals (27). Paradoxically, this bias also resulted in harsher sentencing, with longer institutionalizations for girls who were actually convicted, in comparison with boys arrested for similar offenses (28–31). The self-report literature supports bias in the judicial system; girls report higher rates of antisocial behavior in this context than the official records indicate (32–38).

It is commonly believed that females in our society are less violent than males. However, if violent crimes against family members or same-sex peers are analyzed separately, the gender gap narrows considerably (39), and the rate of violent crimes among girls and women appears to be increasing (13–15, 40). There is also an interaction between race and gender, with black girls arrested for more aggressive acts than white girls (38, 41–44).

Is Antisocial Behavior Among Girls Predominantly Sexual?

Two lines of evidence suggest that this belief is also the result of bias in the judicial process. First, self-reports of delinquency indicate that girls report the same patterns of antisocial behavior as boys, with the exception of sexual assault (32–38). Second, although delinquency statistics demonstrate that girls are convicted of sexual crimes (e.g., prostitution) more frequently than boys, it is important to point out that until the 1970s, arrested girls were frequently subjected to gynecologic examinations (boys did not undergo analogous examinations). Evidence of sexual activity often led to a charge of sexual delinquency, regardless of the initial offense (26). This practice was based on the notion that delinquent girls were the primary vectors for venereal disease (11, 26).

Does Antisocial Behavior of Adolescent Girls Have a Benign Course?

Historically, the belief was that the adult course for these girls was relatively benign (6–11). The most common pathological adult outcome for antisocial boys was adult criminality (1–5); since the prevalence of criminality in women was so low, it was assumed that most antisocial girls “outgrew” their deviance. Furthermore, marriage and childbearing, long considered indications of healthy adult adjustment for any female, were outcomes frequently found among antisocial girls, lending further support to the perception that these girls did relatively well.

The robust relationship between delinquent behavior among boys and criminal behavior among men is an excellent example of what developmental psychopathologists call “homotypic continuity,” i.e., a strong correlation between a disorder at one point in time and the same symptoms at a further point in time. In contrast, “heterotypic continuity” describes the relationship between a disorder at one point in the life cycle and continued dysfunction at another point in time, but with different signs and symptoms (45–47).

For males, the homotypic continuity between adolescent and adult antisocial behavior is stronger when one “looks backward” from adulthood to adolescence than it is in the data from prospective studies. This finding has been interpreted as evidence of desistance from pathological behavior. However, it may actually be an indication of undetected heterotypic continuity, since research has focused so heavily on studying the rate of criminality. Similarly, it is possible that the apparently benign adult course of antisocial girls may, in truth, be a reflection of heterotypic continuity, or continued dysfunction, but with different manifestations in adulthood. The purpose of this review is to summarize what is known about adult outcomes of antisocial adolescent girls, searching for evidence of homotypic continuity, heterotypic continuity, or both.

METHOD

I searched five literature databases for studies on the adult outcomes of antisocial girls: 1) Dissertation Abstracts, 1984–1996 (used to minimize the effect of publication bias); 2) Sociological Abstracts, 1973–1996; 3) Social Work Abstracts, 1977–1996; 4) MEDLINE, 1966–1996; and 5) PsycLit, 1974–1996. The search terms were “girl” and “female” combined individually with “conduct disorder,” “delinquency,” “antisocial,” and “crime.” The references from the search articles were then used to locate other studies.

Studies were used if they met the following criteria: 1) they were written in English; 2) they presented data on girls with conduct disorder or delinquency, ages 13–18, or presented such data on boys and girls in a format suitable for separate analyses of the girls; 3) they reported adult follow-up data on the same subjects, as defined by age ≥19 years (I would have included sequential cohort studies, but none were found); or 4) they presented cross-sectional data on adolescent antisocial behavior for any group of adult women.

RESULTS

General Features of the Studies

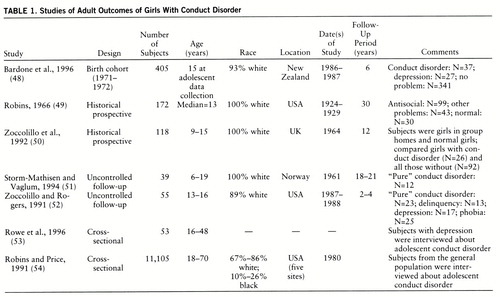

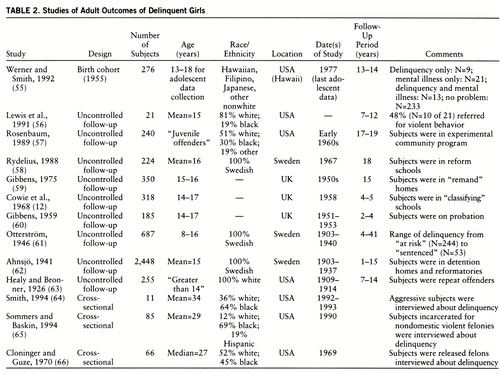

Twenty studies met the inclusion criteria. (Several studies presented relevant data but did not meet the inclusion criteria. A list of these articles is available on request.) The data on mortality, criminality, psychiatric morbidity, marriage, parenting, education, occupation, and service utilization are presented below. Table 1 and table 2 summarize the general features of the studies of girls with conduct disorder and delinquent girls, respectively. The investigations span most of this century. Since conduct disorder is a relatively recent diagnostic category, as discussed above, the earlier studies focused on delinquent girls. The most commonly used design was the uncontrolled follow-up study, and follow-up periods ranged from 1 to 41 years, with a median of 15 years. I found five cross-sectional investigations that presented data on the adolescent antisocial behavior of women who were depressed, incarcerated, or from the general population in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. There is a striking paucity of black subjects across the studies of adolescents, although four of the five cross-sectional investigations included black women.

Mortality

Adult mortality rates were reported in 10 studies. Five of the 10 studies reported mortality rates of 6%–11% (49, 51, 52, 56, 58), and rates of 0%–2% were found in the other five (12, 55, 61–63). Investigations conducted after 1960 reported higher death rates, except for the Kauai Longitudinal Study (55), which reported a rate of 0%.

The highest mortality rates were found for girls with conduct disorder and delinquent girls who either were in reform schools or had comorbid neuropsychiatric impair~ment. The proportions were similar, in spite of follow-up intervals ranging from 2–4 years to 30 years, suggesting that most of the deaths occurred in early adulthood.

Three studies provided comparison data from the normal population. In one study (49), 7% of a conduct disorder sample had died 30 years later (all of the deaths were natural), compared to 5% of the nonantisocial patients and 10% of the control subjects. The population-based death rate for women at the time was 7%. The 18-year mortality rate in a study of the population of all Swedish girls committed to “state-run probationary schools” (58) was 10% (77% of the deaths were violent), compared to an expected rate of 1.1%–2.6% in the general population. In a 2- to 4-year uncontrolled follow-up of girls with conduct disorder from an inpatient unit (52), it was reported that 6% of the girls had died violently. The age-matched normal population rate for violent deaths was 0.034%.

Criminality

Sixteen studies reported data on adult crime. All used arrest data, except the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study (48), which used a self-report inventory of illegal activities. Four prospective studies of girls with conduct disorder reported adult crime rates ranging from 33% to 50% (48, 49, 51, 52). The crime rate in adulthood for delinquent girls ranged from 10% to 96%, although the rates clustered around 25%–46% in the majority of the studies (12, 55–57, 59–63). Adult crime rates were higher in all groups of antisocial girls than in any group of either normal control subjects or girls with other psychiatric problems.

The highest rates of adult criminality (71% and 96%) were found in two follow-up studies of delinquent girls (56, 57). These women were also unusual in that they committed crimes such as burglary and assault, rather than the usual “female” crimes of shoplifting, drug use, and prostitution. The lowest prevalence of adult criminality (10%–25%) was found in samples of girls on probation or institutionalized in less confining settings (12, 60–62). These girls probably were less severely antisocial at baseline. Girls with psychiatric comorbidity had the highest rates of adult criminality in two of three studies (55, 56), but the rates were similar in a third that compared criminal activity among conduct-disordered girls with and without depression (48).

In cross-sectional investigations of incarcerated women, one study (66) reported that 35% of them had been arrested as juveniles. Another study (64) found that 73% of a sample of convicted felons had histories of delinquency and that most had been charged with criminal offenses (in contrast to status offenses). However, this group was very aggressive, and all the women had histories of severe abuse. Violent female offenders in another study (65) reported that 56% of them had engaged in fights, 38% had carried weapons, and 74% had been truant.

Psychiatric Morbidity

Psychiatric morbidity, as defined by outcomes varying from commitment to an institution to formally diagnosed disorders, was investigated in 12 studies; three studies (48–50) compared girls with conduct disorder and normal girls. Fourteen percent to 60% of the girls with conduct disorder had adult psychiatric problems, compared to 0%–40% of the normal girls, depending on whether disorders or hospitalizations were counted. Another study (55) reported that 13% of a group of delinquent girls with comorbid psychiatric disorders had adult symptoms, but that none of the girls who were only delinquent developed psychiatric problems.

Six uncontrolled follow-up studies (12, 51, 52, 56, 59, 62) reported that 23%–38% of girls with conduct disorder and 3%–90% of delinquent girls demonstrated psychopathology as adults. Four studies provided data on the continuity between adolescent antisocial behavior and antisocial personality disorder. Robins's study (49) demonstrated that antisocial girls as women had higher rates of antisocial personality disorder than either normal control subjects or other types of former patients. This relationship was confirmed in a birth cohort study (48), where mean scores on an antisocial personality disorder symptom scale were significantly higher for young women with baseline conduct disorder than for women who were normal or depressed as adolescents. In another study (50), 35% of the girls with conduct disorder met the criteria for antisocial personality disorder as adults, compared to 0% of the girls without conduct disorder. An uncontrolled follow-up (51) identified antisocial personality disorder in 23% of women with histories of conduct disorder. Examination of the ECA data (54) revealed strong continuity between conduct disorder and externalizing disorders.

Investigators have also studied the rates of adult hysteria, substance abuse, and depression in antisocial girls. Robins (49) reported that 21% of the referred antisocial girls became women with hysteria. Others (50) reported that 42% of girls with conduct disorder developed a “dramatic” personality disorder as young women; 55% of these also met the criteria for antisocial personality disorder. A cross-sectional study of female criminals (66) revealed that 65% of them met criteria for sociopathy and 40% met criteria for hysteria.

Four studies (49, 51, 52, 56) demonstrated that 40%–70% of girls with conduct disorder or delinquency develop substance abuse problems as women. Suicidal behavior was the most commonly used measure of depression, and rates were as high as 90% (52, 56). When depression was formally measured (48), rates were much lower. In light of these data, the suicidal behavior may have resulted from either antisocial personality disorder or substance abuse, rather than an affective disorder. In support of this interpretation, Rowe et al. (53) reported that 62% of depressed women had no history of conduct disorder, 25% had one or two symptoms, and only 13% had three or more symptoms. A history of conduct disorder had no effect on the course of depression or response to treatment.

Parenting Behavior

Three studies presented data on parenting skills. In Robins's study (49), 36% of the offspring of mothers with histories of conduct disorder were placed outside the home, a rate higher than that for either normal women or other former patients. These mothers had sons with higher arrest rates than the sons of other women or the sons of men who had been antisocial adolescents.

Mothers in the Kauai Longitudinal Study (55) who had been delinquent had a higher rate of family court involvement than other women. Thirty-three percent of the women with delinquency plus psychiatric problems had a family court record, compared to 8% of the delinquency-only group and 4% of the control subjects. Similarly, in a sample of neuropsychiatrically impaired delinquent girls (56), 15 of 21 became pregnant, and 80% of them could not provide safe, stable environments for their children.

Marriage

The proportions of antisocial girls who married ranged from 19% to 100%, depending on the length of follow-up and the age of the subjects (12, 48–50, 55, 56, 66). There was a trend toward early marriage. In one sample (49), 21% of the antisocial girls married before the age of 17, compared to 9% of the normal control subjects and 8% of the nonantisocial former patients. Thirty-three percent of female criminals with past histories of delinquency reported that they had married before they were 18 years old (66). In another study (48), even those who were not married had a higher rate of early cohabitation.

Four studies presented data on the quality of these relationships. In one investigation (49), antisocial girls developed into women with higher rates of divorce and extramarital sexual activity than either normal control subjects or other types of patients. Sixty-five percent of the antisocial group had marital problems, including many women who were married to abusive or alcoholic men. This finding was replicated in a sample of neuropsychiatrically ill delinquent girls (56); 10% of these subjects were divorced by their early 20s, and 62% of those living with a partner were in violent relationships. Girls with conduct disorder at 21 years of age were 3.9 times more likely to have been involved in a mutually violent relationship than either normal or depressed control girls (48). None of the delinquent girls in the Kauai Longitudinal Study (55) were happy in their marriages; one-third of them ranked their marriage as their biggest concern, compared to 14% of the normal control subjects.

Education and Occupation

Academic achievement and occupational success were assessed by six studies each. In the Kauai Longitudinal Study (55), 40% of the delinquent subjects did not go beyond high school, compared to 9% of the group without problems. Similarly, in the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study (48), girls with conduct disorder were 3.8 times more likely to have no school certificate (similar to a high school diploma) than the healthy control subjects, although depressed girls were 5.8 times more likely to demonstrate this outcome. In two uncontrolled follow-ups of clinical samples (52, 56), only 10%–29% of the subjects had completed high school.

The data on occupational outcomes are conflicting. One study (49) reported that 15% of the women with antisocial histories were unemployed, compared to 7% of the other former patients and 0% of the normal control subjects. Eleven percent of the antisocial group reported 10 or more jobs in the previous 10 years, compared to 1% of the other former patients and 0% of the normal control subjects. In another follow-up of more impaired delinquent girls (56), only 29% had any job training, with histories of moving from one low-paying job to another. However, an uncontrolled follow-up of delinquent girls on probation (60) found that 48% of them had “good or very fair records” of work. Zoccolillo et al. (50) reported that only 7% of women with conduct disorder had a history of occupational problems, similar to the rate of 9% for women without conduct disorder. There were no differences in employment outcomes between women in the conduct disorder, depressed, and normal groups of the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study (48).

Service Utilization

Service utilization outcomes included welfare, involvement with social services agencies (e.g., child protection agencies), and medical care. Social services were required by 55% of women with antisocial histories, compared to 35% of nonantisocial patients and 10% of normal control subjects (49). The antisocial group also had the highest rate of physician utilization: 23% versus 0% for the nonantisocial group and 10% for the normal control subjects. Women with conduct disorder histories in the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study (48) were 3.7 times more likely to use multiple sources of welfare than healthy control subjects or depressed girls, a finding similar to results from two other studies (56, 61).

Global Adult Functioning

With a simple summary measure of adult functioning, Robins (49) found that nearly one-half of antisocial adolescent girls developed into adults with poor adjustment in multiple domains. Similarly, the girls with conduct disorder in the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study (48) averaged nearly three adult adjustment problems, compared to one for the normal control subjects and two for the depressed girls. The delinquent girls in the Kauai Longitudinal Study (55) had more problems coping with adult life. Women with histories of delinquency plus mental health problems had the worst outcome, 42% of them having two or more coping problems, compared to 12% of the normal women, 25% of the delinquency-only group, and 26% of the girls with only psychiatric problems.

Zoccolillo et al. (50) found that a past history of conduct disorder was not strongly associated with any one specific adverse outcome, but that 62% of the girls with conduct disorder had difficulties in two or more domains of adult functioning, compared to 9% of the girls without conduct disorder. Two uncontrolled follow-ups of girls with conduct disorder (51, 52) reported that nearly 20% of each sample adjusted poorly to adulthood.

DISCUSSION

These data indicate that the adult course for many adolescent girls with antisocial behavior is not benign. Compared to their nonantisocial peers, these women have higher mortality rates, a 10- to 40-fold increase in criminal behavior, a variety of psychiatric problems, dysfunctional and sometimes violent relationships, poor educational achievement, less stable work histories, and higher rates of service utilization.

Continuity Between Adolescent and Adult Pathology

The data clearly support a model of homotypic continuity. At least 25%–50% of antisocial girls engage in adult criminal behavior, and recent delinquency follow-up studies suggest that the rates may be even higher in contemporary cohorts. The cross-sectional studies report that 60%–80% of women with criminal records have histories of antisocial behavior as teenagers. Taken together, these findings imply that antisocial behavior in adolescence is the initial step in the predominant pathway to female adult crime.

Do these girls have an antisocial lifestyle that simply persists into adulthood? Do they start with minor infractions, progressing to more severe criminal behavior? Is there a pattern of misconduct followed by a quiescent period, then emergence of a different type of crime in adulthood? Anecdotal and retrospective data suggest that there are at least two paths between antisocial deviance in girls and such behavior in women (14, 64, 65, 67, 68). The first is a pattern of persistent, aggressive antisocial behavior beginning during latency and continuing throughout adolescence into adulthood, with a steady increase in the severity and aggressiveness of offenses. The second path is characterized by norm violations starting in the teen years, escalating to more severe adult criminal activity in the context of substance abuse or continued association with deviant peers. These paths are similar to some of those described in boys (4, 5, 69–71), although the findings need to be replicated in controlled prospective studies of girls.

Antisocial behavior among adolescent girls was not associated just with adult crime. Regardless of the outcome measure used, the studies reported that substantial percentages of antisocial girls did poorly in adulthood. This multiplicity of adverse outcomes may be a reflection of 1) latent heterogeneity in the population, with subgroups of girls who at baseline may have different prognoses (susceptibility bias) or 2) a large proportion of antisocial girls who display problems in multiple domains of adult life (heterotypic continuity). The data indicate that both conditions may be in operation.

It is quite probable that the population of antisocial girls contains subgroups defined by baseline characteristics that may have prognostic significance, for example, aggression, psychiatric comorbidity, history of abuse, or family dynamics. If a correction for this heterogeneity is not made in the sampling process or in the data analysis, adverse outcomes may show up in every domain. However, this would be a reflection of susceptibility bias, with each of the subgroups developing the outcomes unique to them, rather than a reflection of the majority of the girls having widespread pathology.

In support of this explanation, several studies examined the effects of baseline aggression or psychiatric comorbidity and reported that groups of girls with these characteristics each had sets of outcomes different from those of the girls without them (12, 48, 52, 55, 56, 62). Future cross-sectional studies of antisocial girls and women should be designed to identify subgroups with potentially different outcomes. Similarly, longitudinal stud~ies should include measurements of the prognostic effects of aggression and baseline psychiatric comorbidity as well as explore the effects of variables such as history of abuse, family psychiatric history, and family functioning.

Although susceptibility bias could explain the variety of untoward outcomes, six studies (48–52, 55) reported that one-half of the girls had serious problems in multiple domains of their adult lives, data that clearly support a model of heterotypic continuity. There are two possible mechanisms for heterotypic continuity: 1) there may be a core biological or psychological deficit underlying symptoms in both stages of life, or 2) adolescent antisocial behavior may derail the normal developmental process so significantly in these girls that it seriously compromises their ability to cope with adulthood.

A core biological or psychological deficit would generate a picture of heterotypic continuity by producing maladaptive behavior across all adult domains. Several biological or psychological abnormalities have been associated with antisocial behavior (primarily in males) and could potentially be the mechanism(s) for heterotypic continuity, but I will discuss only the two most likely deficits—prefrontal lobe dysfunction and poor attachment.

Prefrontal lobe dysfunction has been suggested as a potential biological deficit in antisocial behavior (72, 73). Abnormalities in one or all of the three prefrontal lobe circuits responsible for executive functions, mood regulation, and motivation would result in women characterized by impulsivity, short attention span, difficulty planning or delaying gratification, inability to learn from experience, mood instability, and poor motivation, all of which would impair normal adult functioning. Research into the relationship between prefrontal lobe function and antisocial behavior has predominantly focused on executive functions in deviant males (73). Two studies that included antisocial girls (74, 75), however, reported that girls with inattention, distractibility, and impulsivity had higher rates of psychosocial impairment. We have no data on any other aspects of prefrontal lobe function and no research using more sophisticated diagnostic techniques such as imaging. Further research should be done on the role of prefrontal lobe dysfunction in antisocial females.

A core psychological deficit in attachment has long been postulated as an etiologic factor in antisocial behavior (76) but could also be the mechanism for the heterotypic continuity reported here. Poor attachment has been associated with the inability to form and maintain stable adult relationships with partners, children, peers, and co-workers. This could certainly explain the pervasive dysfunction in women with histories of adolescent antisocial behavior. Most of the studies on the effects of attachment are cross-sectional, use self-report delinquency measures, and have been done on males, but several (77–79) have studied female adolescents and reported that attachment difficulties are associated with antisocial behavior. We clearly need to investigate the developmental effect of poor attachment as a factor in adverse adult outcomes.

The second possible mechanism explaining heterotypic continuity is interference with normal adolescent development. This derailment may occur because antisocial behavior prevents girls from learning the social and psychological skills needed for adulthood, or because antisocial conduct may expose girls to situations in which each behavioral choice leads to further deviance. There are no data with which to test this hypothesis, but prospective studies of development in girls with other types of problems, such as early puberty, histories of institutionalization, or depression (80–83), indicate that such experiences can derail normal development and lead to multiple poor outcomes in adulthood. We need to collect detailed longitudinal data from antisocial females about the impact of their behaviors on their daily lives. To determine whether antisocial deviance has a uniquely deleterious effect on development, comparison data should also be collected from normal girls and girls with other psychiatric disorders.

Limitations of the Studies

Although the results of this review are provocative, it is important to point out limitations of the studies. The most significant is the absence of data on the nonwhite female population. This is particularly troubling given the higher arrest rate for black females. Few of the studies used control groups, many samples were small, and larger samples were often heterogeneous with regard to type of antisocial behavior. A variety of data collection methods were used, ranging from public registries to clinical interviewing. There was an assortment of outcome measures, and cohort effects were of particular concern in the definition of conduct disorder, changes in the definition of sexual deviance, and changes in institutionalization practices over the past century.

Directions for Future Research

In spite of these limitations, this review establishes that female antisocial behavior has important individual and societal consequences. The studies reviewed here suggest that if we do a 10-year follow-up on Jennifer, described at the beginning of this article, we are likely to find that she has not graduated from high school, has had multiple, unstable relationships, is using drugs and alcohol, uses aggression to solve conflicts, has received psychiatric and social services, has been in jail, and has had difficulties caring for her children. Our understanding of the developmental trajectories of antisocial girls and women is so limited, however, that as policy makers or clinicians, we do not know how to prevent or treat such outcomes.

Several lines of research should be developed to resolve these issues. In all types of studies, particular emphasis should be placed on including antisocial females from nonwhite populations, and comparison data should be collected not only from normal females but from psychiatric groups as well. The first type of further research needed is phenomenological studies of antisocial girls and women. This would allow us to assess the validity of our current diagnostic criteria for conduct disorder in girls (20) as well as identify variables in adolescence that may have long-term prognostic value, such as aggression, psychiatric comorbidity, and type of delinquent behavior. Second, we need cross-sectional studies of the rates of prefrontal lobe dysfunction and poor attachment in antisocial females to determine whether these are important factors in the trajectories to adult pathology. Third, the next generation of longitudinal studies on antisocial adolescent girls should be designed with multiple data collection points, should track subgroups of antisocial girls with potentially different prognoses, and should assess brain and psychological changes over time. Data from these three types of studies will give us the knowledge necessary to develop treatment and secondary prevention strategies for girls like Jennifer.

|

|

Received June 9, 1997; revision received Nov. 18, 1997; accepted Dec. 4, 1997. From the Department of Psychiatry, Allegheny University of the Health Sciences. Address reprint requests to Dr. Pajer, Allegheny University of the Health Sciences, Allegheny Campus, Four Allegheny Center, Suite 806, Pittsburgh, PA 15212; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grant MH-01285. The author thanks George Vaillant, M.D., Magda Stouthamer-Loeber, Ph.D., and Rolf Loeber, Ph.D., for discussions that provided the impetus for this review and William Gardner, Ph.D., for detailed comments on an earlier draft of the paper.

1 Glueck S, Glueck E: Juvenile Delinquents Grown Up. New York, Commonwealth Fund, 1940Google Scholar

2 McCord W, McCord J: Psychopathy and Delinquency. New York, Grune & Stratton, 1956Google Scholar

3 West DJ, Farrington DP: The Delinquent Way of Life. London, Heinemann, 1977Google Scholar

4 Loeber R: The natural histories of juvenile conduct problems, substance use and delinquency: evidence for development progressions. Advances in Clin Psychol 1988; 2:73–124Google Scholar

5 Moffitt TE: Adolescent-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev 1993; 100:674–701Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Thomas WI: The Unadjusted Girl. Boston, Little, Brown, 1937Google Scholar

7 Cohen A: Delinquent Boys. Glencoe, Ill, Free Press, 1955Google Scholar

8 Cloward R, Ohlin LE: Delinquency and Opportunity. New York, Free Press, 1960Google Scholar

9 Morris RR: Female delinquency and relational problems. Social Forces 1964; 43:82–89Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Smith LS: Sexist assumptions and female delinquency, in Women, Sexuality and Social Control. Edited by Smart C, Smart B. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978, pp 72–88Google Scholar

11 Kunzel RG: Fallen Women, Problem Girls: Unmarried Mothers and the Professionalization of Social Work, 1890–1945. New Haven, Conn, Yale University Press, 1993Google Scholar

12 Cowie J, Cowie V, Slater E: Delinquency in Girls. London, Heine~mann, 1968Google Scholar

13 Loper AB, Cornell DG: Homicide by juvenile girls. J Child and Family Studies 1996; 5:323–336Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Mann CR: When Women Kill. Albany, State University of New York Press, 1996Google Scholar

15 Molidor CE: Female gang members: a profile of aggression and victimization. Soc Work 1996; 41:251–257Medline, Google Scholar

16 Smith L: In suburbs, concern grows over girls' criminal activity. Washington Post, Oct 20, 1995, p A1Google Scholar

17 Mehren E: The throwaways. Los Angeles Times, April 12, 1996, p E1Google Scholar

18 Mehren E: As bad as they wanna be. Los Angeles Times, May 17, 1996, p E1Google Scholar

19 Myers WC, Burket RC, Lyles WB, Stone L, Kemph JP: DSM-III diagnoses and offenses in committed female juvenile delinquents. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law 1990; 18:47–54Medline, Google Scholar

20 Zoccolillo M: Gender and the development of conduct disorder. Developmental Psychopathology 1993; 5:65–78Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Kashani JH, Orvaschel H, Rosenberg TK, Reid JC: Psychopathology in a community sample of children and adolescents: a developmental perspective. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1989; 28:701–706Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT: Prevalence and comorbidity of DSM-III-R diagnoses in a birth cohort of 15-year-olds. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1993; 32:1127–1134Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 May D: Delinquent girls before the courts. Med Sci Law 1977; 17:203–212Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Offord DR, Abrams N, Allen N, Poushinsky M: Broken homes, parental psychiatric illness, and female delinquency. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1979; 49:252–264Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Chesney-Lind M: Girls and status offenses: is juvenile justice still sexist? Criminal Justice Abstracts 1988; 20:144–165Google Scholar

26 Odem ME: Delinquent Daughters: Protecting and Policing Adolescent Female Sexuality in the United States, 1885–1920. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1995Google Scholar

27 Westendorp F, Brink KL, Roberson MK, Ortiz IE: Variables which differentiate placement of adolescents into juvenile justice or mental health systems. Adolescence 1986; 21:23–37Medline, Google Scholar

28 Chesney-Lind M: Judicial enforcement of the female sex role: the family court and the female delinquent. Issues in Criminology 1973; 8:51–69Google Scholar

29 Datesman SK, Scarpitti FR: Female delinquency and broken homes: a reassessment. Criminology 1975; 13:33–55Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Sarri R: Unequal protection under the law: women and the criminal justice system, in The Trapped Woman: Catch-22 in Deviance and Control. Edited by Figueira-McDonough J, Sarri R. Beverly Hills, Calif, Sage Publications, 1987, pp 394–426Google Scholar

31 Schwartz IM, Steketee MW, Schneider VW: Federal juvenile justice policy and the incarceration of girls. Crime and Delinquency 1990; 36:503–520Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Vaz EW: Middle-Class Juvenile Delinquency. New York, Harper & Row, 1967Google Scholar

33 Williams JR, Gold M: From delinquent behavior to official delinquency. Social Problems 1972; 19:209–228Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Hindelang MJ: Age, sex, and the versatility of delinquent involvements. Social Problems 1971; 18:522–534Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Cernkovich SA, Giordano PC: A comparative analysis of male and female delinquency. Sociological Quarterly 1979; 20:131–145Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Figueira-McDonough J, Barton WH, Sarri RC: Normal deviance: gender similarities in adolescent subcultures, in Comparing Female and Male Offenders. Edited by Warren MQ. Beverly Hills, Calif, Sage Publications, 1981, pp 17–45Google Scholar

37 Loy P, Norland S: Gender convergence and delinquency. Sociological Quarterly 1981; 22:275–283Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Wolfgang M: Delinquency in two birth cohorts. Am Behavioral Scientist 1983; 27:75–80Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Balthazar ML, Cook RJ: An analysis of the factors related to the rate of violent crimes committed by incarcerated female delinquents. J Offender Counseling, Services, and Rehabilitation 1984; 19:103–118Google Scholar

40 Durant RH, Getts AG, Cadenhead C, Woods ER: The association between weapon carrying and the use of violence among adolescents living in and around public housing. J Adolesc Health 1995; 17:376–380Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41 Lewis DK: Black women offenders and criminal justice, in Comparing Female and Male Offenders. Edited by Warren MQ. Beverly Hills, Calif, Sage Publications, 1981, pp 89–105Google Scholar

42 Lewis DO, Shanok SS, Pincus JH: A comparison of the neuropsychiatric status of female and male incarcerated delinquents: some evidence of sex and race bias. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry 1982; 21:190–196Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43 Farnworth M, McDermott J, Zimmerman SE: Aggregation effects on male-to-female arrest rate ratios in New York State, 1972–1984. J Quantitative Criminology 1988; 4:121–135Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Sommers I, Baskin D: Sex, race, age, and violent offending. Violence Vict 1992; 7:191–201Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45 Rutter M: Pathways from childhood to adult life. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1989; 30:23–51Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46 Rutter M: Adolescence as a transition period: continuities and discontinuities in conduct disorder. J Adolesc Health 1992; 13:451–460Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47 Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ: Perspectives on developmental psychopathology, in Developmental Psychopathology, vol 1: Theory and Methods. Edited by Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1995, pp 3–20Google Scholar

48 Bardone AM, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Dickson N, Silva PA: Adult mental health and social outcomes of adolescent girls with depression and conduct disorder. Developmental Psychopathology 1996; 8:811–829Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Robins LN: Deviant Children Grown Up: A Sociological and Psychiatric Study of Sociopathic Personality. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1966Google Scholar

50 Zoccolillo M, Pickles A, Quinton D, Rutter M: The outcome of childhood conduct disorder: implications for defining adult personality disorder and conduct disorder. Psychol Med 1992; 22:971–986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51 Storm-Mathisen A, Vaglum P: Conduct disorder patients 20 years later: a personal follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 89:416–420Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52 Zoccolillo M, Rogers K: Characteristics and outcome of hospitalized adolescent girls with conduct disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1991; 30:973–981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53 Rowe JB, Sullivan PF, Mulder RT, Joyce PR: The effect of a history of conduct disorder in adult major depression. J Affect Disord 1996; 37:51–63Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54 Robins LN, Price RK: Adult disorders predicted by childhood conduct problems: results from the NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area Project. Psychiatry 1991; 54:116–132Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55 Werner EE, Smith RS: Overcoming the Odds: High Risk Children From Birth to Adulthood. Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press, 1992Google Scholar

56 Lewis DO, Yeager CA, Cobham-Portorreal CS, Klein N, Showalter C, Anthony A: A follow-up of female delinquents: maternal contributions to the perpetuation of deviance. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1991; 30:197–201Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57 Rosenbaum JL: Family dysfunction and female delinquency. Crime and Delinquency 1989; 35:31–44Crossref, Google Scholar

58 Rydelius PA: The development of antisocial behavior and sudden death. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1988; 77:398–403Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59 Gibbens TCN: Female offenders. Br J Psychiatry 1975; 9:326–333Google Scholar

60 Gibbens TCN: Supervision and probation of adolescent girls. Br J Delinquency 1959; 10:84–103Google Scholar

61 Otterström E: Delinquency and children from bad homes: a study of their prognosis from a social point of view. Acta Paediatr 1946; 33(suppl 5):1–326Google Scholar

62 Ahnsjö S: Delinquency in girls and its prognosis. Acta Paediatr 1941; 28(suppl 3):1–327Google Scholar

63 Healy W, Bronner AF: Delinquents and Criminals: Their Making and Unmaking. New York, Macmillan, 1926Google Scholar

64 Smith V: The Experiences of Women Who Are Aggressive: An Analysis of Incarcerated Women From a Gestalt Therapy Theoretical Perspective (doctoral dissertation). Cincinnati, The Union Institute, 1994Google Scholar

65 Sommers I, Baskin DR: Factors related to female adolescent initiation into violent street crime. Youth and Society 1994; 25:468–489Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Cloninger CR, Guze SB: Psychiatric illness and female criminality: the role of sociopathy and hysteria in the antisocial woman. Am J Psychiatry 1970; 127:303–311Link, Google Scholar

67 Gilfus ME: From victims to survivors to offenders: women's routes of entry and immersion in street crime. Women and Criminal Justice 1992; 4:63–89Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Dunlap E, Johnson BD, Manwar A: A successful female crack dealer: a case study of a deviant career. Deviant Behavior 1994; 15:1–25Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Loeber R, LeBlanc M: Toward a developmental criminology, in Crime and Justice, vol 12. Edited by Tonry M, Morris N. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1990, pp 375–473Google Scholar

70 Sampson RJ, Laub JH: Crime in the Making: Pathways and Turning Points Through the Life Course. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1990Google Scholar

71 Nagin DS, Farrington DP: The onset and persistence of offending. Criminology 1992; 30:501–523Crossref, Google Scholar

72 Pennington BF, Ozonoff S: Executive functions and developmental psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1996; 37:51–87Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

73 Scarpa A, Raine A: Biology of wickedness. Psychiatr Annals 1997; 27:624–629Crossref, Google Scholar

74 Moffitt TE, Henry B: Neuropsychological assessment of executive functions in self-reported delinquents. Developmental Psychopathology 1989; 1:105–118Crossref, Google Scholar

75 Aronowitz B, Liebowitz M, Hollander E, Fazziui E, Durlach-Misteli C, Frenkel M, Mosovich S, Garfinkel R, Saoud J, DelBene D, Cohen L, Jaeger A, Rubin AL: Neuropsychiatric and neuropsychological findings in conduct disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1994; 6:245–249Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

76 Fonagy P, Target M, Steele M, Steele H: The development of violence and crimes as it relates to security of attachment, in Children in a Violent Society. Edited by Osofsky JD. New York, Guilford Press, 1997, pp 150–177Google Scholar

77 Gardner L, Shoemaker DJ: Social bonding and delinquency: a comparative analysis. Sociological Quarterly 1989; 30:481–500Crossref, Google Scholar

78 Seydlitz R: The effects of age and gender on parental control and delinquency. Youth and Society 1991; 23:175–201Crossref, Google Scholar

79 Torstensson M: Female delinquents in a birth cohort: tests of some aspects of control theory. J Quantitative Criminology 1990; 6:101–115Crossref, Google Scholar

80 Brown GW: Causal paths, chains and strands, in Studies of Psychosocial Risk: The Power of Longitudinal Data. Edited by Rutter M. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 1988, pp 285–314Google Scholar

81 Caspi A, Elder GH: Emergent family patterns: the intergenerational construction of problem behaviors and relationships, in Relationships Within Families: Mutual Influences. Edited by Hinde A, Stevenson-Hinde J. Oxford, England, Clarendon Press, 1988, pp 218–240Google Scholar

82 Magnusson D: Individual Development From an Interactional Perspective: A Longitudinal Study. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erl~baum Associates, 1988Google Scholar

83 Quinton D, Rutter M: Parental Breakdown: The Making and Breaking of Intergenerational Links. Aldershot, England, Gower, 1988Google Scholar