Genetic and Environmental Influences on Trauma Exposure and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms: A Twin Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) develops in only a subset of persons exposed to traumatic stress, suggesting the existence of stressor and individual differences that influence risk. In this study the authors examined the heritability of trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms in male and female twin pairs of nonveteran volunteers. METHOD: Scores on a traumatic events inventory and a DSM-IV PTSD symptom inventory were examined in 222 monozygotic and 184 dizygotic twin pairs. Biometrical model fitting was conducted by using standard statistical methods. RESULTS: Additive genetic, common environmental, and unique environmental effects best explained the variance in exposure to assaultive trauma (e.g., robbery, sexual assault), whereas exposure to nonassaultive trauma (e.g., motor vehicle accident, natural disaster) was best explained by common and unique environmental influences. PTSD symptoms were moderately heritable, and the remaining variance was accounted for by unique environmental experiences. Correlations between genetic effects on assaultive trauma exposure and on PTSD symptoms were high. CONCLUSIONS: Genetic factors can influence the risk of exposure to some forms of trauma, perhaps through individual differences in personality that influence environmental choices. Consistent with symptoms in combat veterans, PTSD symptoms after noncombat trauma are also moderately heritable. Moreover, many of the same genes that influence exposure to assaultive trauma appear to influence susceptibility to PTSD symptoms in their wake.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is unique among anxiety disorders in that it is defined in the context of exposure to an extremely stressful traumatic event. Recent experience has shown that individuals vary markedly in their tendency to experience posttraumatic stress symptoms (1, 2). In fact, considerable research has been focused on delineating characteristics of the traumatic stressor that increase its propensity for causing PTSD. Within uniform types of trauma (e.g., combat), greater duration or intensity of exposure to the trauma tends to increase risk for PTSD (i.e., a dose-response relationship is evident) (3–6). Across different types of trauma, differences in associated risk for PTSD are also evident. Sexual trauma and combat, for example, are associated with very high conditional risks for PTSD (7–10). In general, events that involve the element of interpersonal assault (e.g., rape, violence by an intimate partner, other violent crime) carry higher risks for PTSD than events that lack this element (e.g., motor vehicle accidents, natural disasters) (8, 11–13).

Although characteristics of the traumatic stressor have been shown to influence risk for PTSD, these fail to explain much of the variance in PTSD rates among exposed persons. This has generated interest in individual differences that may influence PTSD susceptibility. Among such factors, most studies have shown that female gender (5, 6, 10, 14–17) and low IQ (18, 19) increase risk for PTSD following trauma exposure. In addition, a number of studies have shown that some premorbid personality characteristics (e.g., neuroticism) (16, 20, 21) and preexisting anxiety or depressive disorders (7, 22–24) increase risk for PTSD. The latter findings have been extended to include a family history of anxiety or depressive disorders (25–28), raising the possibility of genetic susceptibility factors for PTSD (29–31).

Support for genetic influences on PTSD symptoms comes from twin studies. In a small twin study of anxiety disorders (fewer than 50 twin pairs were included), PTSD was found only in co-twins of probands with anxiety disorders (32). The other published twin study of which we are aware provides the most compelling evidence for a genetic component to PTSD vulnerability. This is the Vietnam Era Twin Registry study of 4,042 male-male veteran twin pairs (2,224 monozygotic and 1,818 dizygotic pairs) (4, 33). This study showed that genetic factors account for approximately 30% of the variance in PTSD symptoms, even after differences in trauma exposure between twins are taken into account (33). This study also demonstrated genetic influences on extent of trauma exposure (34), highlighting the fact that risk for PTSD must be considered as the outcome of dual processes: risk for exposure to traumatic events, followed by risk for PTSD symptoms following exposure. Risk factors for these two processes may, to some extent, be shared and may involve pretrauma personality characteristics (35).

A recent meta-analysis of the genetic epidemiology of anxiety disorders (36) failed to include PTSD, undoubtedly because of the paucity of data on this topic. In fact, to the best of our knowledge, there are no published twin studies of PTSD symptoms beyond the aforementioned, widely cited Vietnam Era Twin Registry study (4, 33–35). That study included exclusively male combat veterans, meaning that there are no data on heritability in women or on traumatic stressors other than combat. The purpose of the present study was to expand our understanding of the heritability of trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms into a broader context, by including female twin pairs and surveying a broad range of traumatic events.

Method

Subjects

The subjects were 406 volunteer twin pairs recruited from the urban general population in the Vancouver area, British Columbia, Canada (Table 1). The subjects were recruited through media appeals. The study group consisted of 222 monozygotic twin pairs and 184 dizygotic pairs. Zygosity was determined by using a highly accurate questionnaire (37, 38) and examination of recent color photographs. All subjects gave their informed, written consent to participate in this study, which was approved by the Human Subjects Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of British Columbia.

Measures and Procedure

The twin pairs completed a packet of questionnaires at home, a common method used in twin studies. All participants who returned their questionnaires received cash remuneration. The twins were instructed to complete the questionnaires independently of one another in a nondistracting setting.

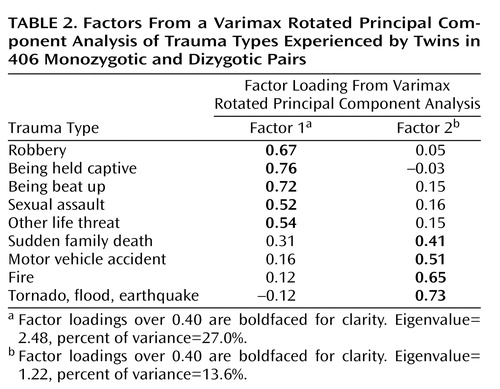

Included was a questionnaire asking about lifetime exposure, at each of three age periods (birth to 6 years, 7 to 16 years, age 17 to current year), to 10 different types of traumatic events. We scored the measure so that each trauma type could range from 0 (never occurred) to 3 (occurred in each of the three age epochs). This scoring method was chosen to take into account information about multiple exposures to trauma types over time; when we analyzed the factor structure (see next section) by using dichotomous scores, similar results were obtained. This questionnaire, used in a recent study from our group (39), is a pencil-and-paper adaptation of questions used in our previous telephone epidemiologic survey of PTSD (40). Combat exposure was not included in the analyses because it was endorsed by very few of these Canadian subjects; therefore, there were a total of nine possible trauma types (Table 2).

Persons who endorsed at least one of the traumatic events (N=612 or 75.4% of the total number of individuals) were asked to answer the succeeding questions in reference to the event that most disturbed them and to focus on the period of time following the disturbing event when they were most troubled or upset. They then answered 17 questions (0=not at all bothered, 1=a little bit bothered, 2=somewhat bothered, 3=very much bothered) corresponding to each of the DSM-IV symptoms of PTSD clusters B through D. This part of the questionnaire was adapted (with the permission of the scale developer, Edna Foa, Ph.D.) from the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale, a clinically validated measure of PTSD symptoms (41).

Statistical Analysis

Trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms

Two analyses were conducted. The first subjected the trauma exposure items to a varimax rotated principal component analysis to extract salient factors for trauma exposure, and the scores estimated for each factor were used in the heritability analyses. All available twin pairs were used in this analysis.

The second analysis estimated the heritability of PTSD symptoms. This analysis was conducted by using data from twin pairs in which both members of the pair reported experiencing a traumatic event. Persons who did not experience a qualifying trauma did not complete the PTSD symptom questions; by definition, these persons could not have posttraumatic symptoms. The PTSD symptom items were formed into four subscales, each representing a PTSD symptom cluster: reexperiencing, avoidance, numbing, and hyperarousal. These four dimensions have been confirmed previously (42, 43); a single higher-order factor was also extracted, and we therefore included the total PTSD symptom score in our analyses here.

Three of the most serious biasing effects on heritability analyses are gender, age, and a violation of the “equal environments” assumption, influences that may independently increase twin similarity (thus spuriously inflating/attenuating heritability estimates) for the variables under study. To examine the effect of gender, the heritability analyses were conducted on 1) female twin pairs only, 2) female and male twin pairs only (same-sex pairs), and 3) female, male, and opposite-sex dizygotic twin pairs (the total study group). The influence of age on twin similarity was corrected by computing the standardized residual for trauma and PTSD symptom scores from the stepwise multiple regressions of these scores on age. The equal environments assumption posits that differences between monozygotic and dizygotic twin pairs in the similarity between co-twins are not due to the monozygotic twins, for example, being treated more similarly than twins in dizygotic pairs. These effects were corrected by computing the standardized residual for trauma and PTSD symptom scores from the stepwise multiple regressions of these scores on ratings of several variables indexing the amount of time they spent together, whether they were treated the same way by parents, teachers, and peers, whether they shared the same classes together at school, whether they dressed alike, etc. (44).

Biometrical model fitting

PRELIS 2 (45) was used to estimate co-twin similarity (Pearson’s r) for men in monozygotic pairs, women in monozygotic pairs, men in dizygotic pairs, women in dizygotic pairs, and opposite-sex dizygotic pairs. The method of weighted least squares fitted to Pearson correlations and asymptotic weight matrices was used to estimate heritability by means of the computer program Mx (46). This method allows model fitting to data that show any departure from multivariate normality (47). The basic structural model fit to the data specified additive genetic effects (A), shared environmental effects (C), and nonshared environmental effects (E). Estimates of E also include measurement error because they are computed as the residual variance after the influences of A and C have been removed.

This model was systematically modified to drop A, C, and E effects to test their significance. The fit criteria used to determine the “best-fitting” model were chi-square differences, the principle of parsimony, and root mean square error of approximation. The parameter estimates for the best-fitting model were standardized and squared to form the familiar h2, c2, and e2 estimates (proportions of the total variance attributable to each effect) for each variable. The possibility of sex differences in these parameters was evaluated before we combined all twin pairs for subsequent analyses.

The next analysis, restricted to twins who both had trauma exposure, estimated the degree to which the etiological bases for liability for exposure to trauma and PTSD symptoms are due to a common genetic and environmental basis. This was examined by computing the correlations between the additive genetic effects (rG), shared environmental effects (rC), and nonshared environmental effects (rE) on the trauma and PTSD symptom scores. These correlation coefficients (which are distinct from phenotypic correlations) yield an index that varies from –1.0 to 1.0, reflecting the degree to which two variables are influenced by the same genetic, shared environmental, and nonshared environmental factors, respectively. The covariances of genetic and environmental effects were computed by subjecting the asymptotically weighted within-pair correlations for monozygotic and dizygotic twins to Cholesky decomposition (47) by the method of weighted least squares, as before. The parameter estimates were standardized to form estimates of rG, rC, and rE(46).

Results

Heritable Basis of Trauma Exposure

The responses for each trauma exposure item from each participant were examined for departures from normality and corrected as required. The exposure items were subjected to a varimax principal component analysis that extracted two factors accounting for 40.6% of the total variance (Table 2). Note that combat was not included in the analysis because the rate of endorsement by these subjects was extremely low. Factor 1 appears to represent “assaultive” events, whereas factor 2 describes “nonassaultive” events.

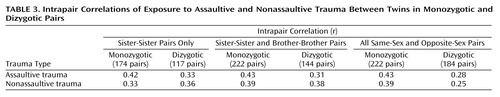

Genetic and environmental influences were estimated by intrapair twin correlations (Pearson’s r) for sister pairs only, sister pairs and brother pairs, and the total group of subjects. These correlations are shown in Table 3. The correlations between monozygotic twins exceeded the correlations between dizygotic twins in all groups for assaultive trauma, suggesting the presence of genetic influences on this variable. For nonassaultive trauma, the correlations between monozygotic twins and between dizygotic twins were approximately equal, suggesting no genetic effects on this variable. The similarity of between-twin correlations in the sister-sister pairs only and in both sister-sister and brother-brother pairs suggests that the magnitudes of genetic and environmental effects are the same in both genders. The inclusion of opposite-sex dizygotic pairs yields a significant drop in the correlation between dizygotic twins, suggesting that although the magnitudes of genetic and environmental effects are the same across gender, they are gender specific (e.g., the genetic loci involved in the liability may differ by gender). This possibility can be tested directly by using sex-limited genetic analyses (47); however, the present study group was not large enough to conduct these analyses. As such, the present analyses estimate only the magnitude of genetic and environmental influences from all etiological sources.

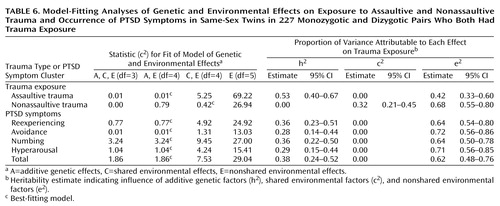

All subsequent analyses were limited to same-sex monozygotic and dizygotic pairs. A model specifying A, C, and E effects provided the most satisfactory explanation for the factor scores for exposure to assaultive trauma. A purely environmental model specifying only C and E effects provided the best explanation for the factor scores for exposure to nonassaultive trauma (Table 4). The values of rC and rE were estimated at 0.31 and –0.20, respectively, suggesting that the environmental influences on assaultive and nonassaultive trauma are largely unrelated.

Heritable Basis of PTSD Symptoms Following Trauma Exposure

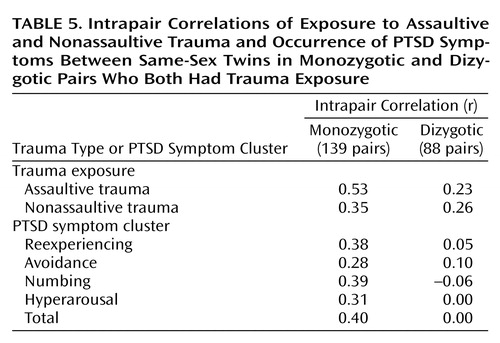

The following analyses were based on same-sex pairs in which both members of the pair reported experiencing some kind of traumatic event: 139 monozygotic pairs (28 brother pairs and 111 sister pairs) and 88 dizygotic pairs (74 sister pairs and 14 brother pairs). Between-twin correlations and results of the model-fitting procedures are presented in Table 5 and Table 6, respectively. In this subgroup of affected twins, additive genetic and nonshared environmental influences best explained the variance in factor scores for assaultive trauma, and a purely environmental model provided the best explanation for the variance in nonassaultive trauma. A model specifying additive genetic and nonshared environmental influences provided the best explanation for the four PTSD clusters and for total PTSD symptoms (Table 6). Heritability estimates for the symptom clusters were moderate (Table 6).

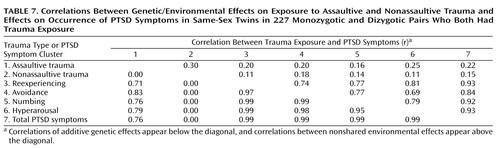

Table 7 presents correlations between the additive genetic effects on trauma exposure and on PTSD symptoms. Notable are the high correlations between the additive genetic effects on assaultive trauma and PTSD symptoms. These findings suggest shared genetic influences on exposure to assaultive trauma and on the experience of PTSD symptoms following exposure.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the heritability of trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms outside of the context of military trauma. Moreover, we believe this is the first study to do so in a group that includes women. Our study is subject to numerous limitations. Most notable among these are the small number of subjects; a low proportion of men; the volunteer nature of the subjects (rather than randomly sampled community subjects), which may limit its representativeness; and our reliance on self-report measures (yielding quantitative indices of exposure and symptoms) rather than direct interviews (which might have yielded qualitative diagnoses).

This latter aspect of our study deserves closer scrutiny. Relying on quantitative measures, when many subjects provide information about the trait(s) of interest, provides us with sufficient statistical power to make stable parameter estimates even in the absence of a huge study group (i.e., thousands of subjects). Lacking diagnostic information (e.g., DSM-IV diagnoses of PTSD), we measured related traits (e.g., PTSD symptoms) that we assume enable us to make inferences about the disorder(s) of interest. In some cases, such as social phobia, where it is clearer that the disorder behaves as if it were, indeed, the extreme end of a normally distributed trait (i.e., social anxiety), this supposition has empirical support (48, 49). But in the case of PTSD, this assumption is unproven, and the relevance of our findings to the clinical realm must be considered in light of this uncertainty. At this juncture, we hope that our findings will stimulate further hypothesis testing in study groups for which information about both symptoms and disorders is available.

With these constraints in mind, let us consider our findings and their possible implications. As noted by Kendler (50), “all heritability estimates are specific to a population with a range of environmental exposures” (p. 108). It is therefore reassuring to find that our heritability estimates for PTSD symptoms come remarkably close to those derived from an exclusively male group of combat veterans from the Vietnam Era Twin Registry (33). These two studies provide an insufficient base from which to extrapolate the heritability of PTSD in other countries and circumstances, but they provide a starting point from which to test this empirically (50).

In this group of twins we were also able to show that exposure to certain classes of trauma (e.g., violent crime) is influenced by both genetic and environmental (shared and nonshared) factors, whereas other classes of trauma (e.g., motor vehicle accidents and natural disasters) are influenced exclusively by shared environmental factors. The notion that individual differences in event proneness are, in part, genetically determined is not new. It is now well established that genetic factors can be associated with particular kinds of environmental exposures, including life events (51, 52), and our findings may be an example of an individual’s genetically determined behavior leading him or her to seek out or engender particular environmental responses. Our number of subjects is insufficient to permit us to declare with certainty that certain kinds of life traumata are genetically determined and that others are not. But our findings are suggestive that violent interpersonal or assaultive trauma and other forms of nonviolent or “anonymous” trauma differ in their genetic influences. This is a hypothesis that can be further tested in other larger, population-based samples.

Given the moderate heritability of most other forms of anxiety (36), it should probably come as no surprise that PTSD symptoms behave similarly. Probably the most interesting part of our study, then, is the finding that genetic influences on trauma exposure and on subsequent PTSD symptoms are substantially overlapping. This raises the question of the pathways and mechanisms by which genes exert these dual influences. One possibility is that genetic influences on “PTSD proneness” might be mediated through personality traits (e.g., neuroticism) that would predispose an individual to assaultive trauma and subsequent PTSD. Simply stated, this model would posit that an individual’s genetically influenced propensity toward neuroticism would lead the individual to experience more anger and irritability, making that person 1) more likely to get into fights (thereby increasing the risk of experiencing assaultive traumata) and 2) more likely to become highly emotionally aroused as a result of experiencing such traumata (thereby increasing the risk for PTSD symptoms). Recently published data from a large twin study by Kendler and colleagues (53) do, in fact, provide evidence that neuroticism is associated with an increased risk for exposure to some kinds of traumatic events. Personality traits other than neuroticism, however, may also play a role. In the Vietnam Era Twin Registry study, which included only men, preexisting conduct disorder (which might be considered an early manifestation of antisocial traits) was a risk factor both for trauma exposure and for subsequent PTSD symptoms (35). Given that our study included predominantly women, the possibility that different personality traits influence trauma exposure and PTSD susceptibility in men (e.g., sociopathy) and women (e.g., neuroticism) should be strongly considered.

Future research in this area would benefit from considering (and measuring) some of the individual differences purported to increase risk for PTSD (e.g., IQ, neuroticism, sociopathy) as possible determinants of these genetic effects. Even at this level of analysis, the possibility of gene-environment interactions must be considered. For example, genetic influences on behaviors that reduce social support (54), a known risk factor for PTSD (16, 23, 55, 56), might drive the increased risk for PTSD symptoms.

Given the near certainty that susceptibility to PTSD symptoms is a complex trait, large numbers of subjects will be required to detect the influence of what are likely to be many genes each of small effect size (57, 58). To date, an association with the dopamine type 2 (D2) receptor (29) is the only published genetic finding on PTSD of which we are aware, and a second study (30) failed to replicate this association. Twin studies such as this have the potential to help define what phenotypes should be the focus of genetic investigation. Our findings suggest that genetic influences on PTSD are probably mediated through a causal pathway that includes genes that simultaneously influence personality (i.e., exposure proneness) and PTSD symptoms following exposure. Identification of these factors and understanding of the mechanisms by which they elicit PTSD will enhance the likelihood that future gene-hunting expeditions in this area will produce robust, replicable results.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Received Dec. 10, 2001; revision received April 24, 2002; accepted May 8, 2002. From the VA San Diego Healthcare System and the Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego; and the Department of Psychiatry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C., Canada. Address reprint requests to Dr. Stein, Anxiety and Traumatic Stress Disorders Program, Department of Psychiatry (0985), University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093-0985; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by Medical Research Council of Canada grant MA-15364 to Drs. Livesley, Jang, and Vernon and by NIMH grant MH-64122 to Dr. Stein. The authors thank Jack Goldberg, Ph.D., for his suggestions.

1. Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, Kilpatrick D, Bucuvalas M, Gold J, Vlahov D: Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:982-987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Schuster MA, Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Collins RL, Marshall GN, Elliott MN, Zhou AJ, Kanouse DE, Morrison JL, Berry SH: A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:1507-1512Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Green BL, Grace MC, Lindy JD, Gleser GC, Leonard A: Risk factors for PTSD and other diagnoses in a general sample of Vietnam veterans. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:729-733Link, Google Scholar

4. Goldberg J, True WR, Eisen SA, Henderson WG: A twin study of the effects of the Vietnam War on posttraumatic stress disorder. JAMA 1990; 263:1227-1232Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. King DW, King LA, Foy D, Keane T, Fairbank J: Posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of female and male Vietnam veterans: risk factors, war-zone stressors, and resilience-recovery variables. J Abnorm Psychol 2000; 108:164-170Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Wolfe J, Erickson DJ, Sharkansky EJ, King DW, King LA: Course and predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder among Gulf War veterans: a prospective analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000; 67:520-528Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Bromet E, Sonnega A, Kessler RC: Risk factors for DSM-III-R posttraumatic stress disorder: findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Epidemiol 1998; 147:353-361Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P: Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:626-632Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Rosenheck RA: Combat trauma: trauma with highest risk of delayed onset and unresolved posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, unemployment, and abuse among men. J Nerv Ment Dis 2001; 189:99-108Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Creamer M, Burgess P, McFarlane AC: Post-traumatic stress disorder: findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Psychol Med 2001; 31:1237-1247Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Stein MB, Walker JR, Forde DR: Gender differences in susceptibility to posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther 2000; 38:619-628Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Golding JM: Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: a meta-analysis. J Fam Viol 1999; 14:99-132Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Ursano RJ, Fullerton CS, Epstein RS, Crowley B, Kao T-C, Vance K, Craig KJ, Dougall AL, Baum A: Acute and chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in motor vehicle accident victims. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:589-595Abstract, Google Scholar

14. Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ, Taylor AE, Loos WR, Forneris CA, Jaccard J: Who develops PTSD from motor vehicle accidents? Behav Res Ther 1996; 34:1-10Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson EL, Schultz LR: Sex differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:1044-1048Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD: Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000; 68:748-766Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ, Epstein RS, Crowley B, Vance K, Kao T-C, Dougall A, Baum A: Gender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder after motor vehicle accidents. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1486-1491Link, Google Scholar

18. McNally RJ, Shin LM: Association of intelligence with severity of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in Vietnam combat veterans. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:936-938Link, Google Scholar

19. Macklin ML, Metzger LJ, Litz BT, McNally RJ, Lasko NB, Orr SP, Pitman RK: Lower precombat intelligence is a risk factor for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998; 66:323-326Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Bramsen I, Dirkzwager AJE, van der Ploeg H: Predeployment personality traits and exposure to trauma as predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms: a prospective study of former peacekeepers. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1115-1119Link, Google Scholar

21. Fauerbach JA, Lawrence JW, Schmidt CW Jr, Munster AM, Costa PT Jr: Personality predictors of injury-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 2000; 188:510-517Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Breslau N, Davis GC, Peterson EL, Schultz L: Psychiatric sequelae of posttraumatic stress disorder in women. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:81-87Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Acierno R, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Saunders BE, Best CL: Risk factors for rape, physical assault, and posttraumatic stress disorder in women: examination of differential multivariate relationships. J Anxiety Disord 1999; 13:541-563Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Perkonigg A, Kessler RC, Storz S, Wittchen H-U: Traumatic events and post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: prevalence, risk factors and comorbidity. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000; 101:46-59Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Davidson JRT, Swartz M, Storck M, Krishnan KRR, Hammett E: A diagnostic and familial study of posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:90-93Link, Google Scholar

26. Davidson JRT, Smith R, Kudler H: Familial psychiatric illness in chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Compr Psychiatry 1989; 30:339-345Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Reich J, Lyons MJ, Cai B: Familial vulnerability factors to post-traumatic stress disorder in male military veterans. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996; 93:105-112Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Yehuda R, Halligan SL, Bierer LM: Relationship of parental trauma exposure and PTSD to PTSD, depressive and anxiety disorders in offspring. J Psychiatr Res 2001; 35:261-270Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Comings DE, Muhleman D, Gysin R: Dopamine DRD2 gene and susceptibility to posttraumatic stress disorder: a study and replication. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 40:368-372Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Gelernter J, Southwick SM, Goodson S, Charney DS, Nagy L: No association between D2 dopamine receptor DRD2 “A” system alleles, or DRD2 haplotypes, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 45:620-625Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Seedat S, Niehaus DJ, Stein DJ: The role of genes and family in trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2001; 6:360-362Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Skre I, Onstad S, Torgesen S, Lygren S, Kringlen E: A twin study of DSM-III-R anxiety disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1993; 88:85-92Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. True WR, Rice J, Eisen SA, Heath AC, Goldberg J, Lyons MJ, Nowak J: A twin study of genetic and environmental contributions to liability for posttraumatic stress symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:257-264Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Lyons MJ, Goldberg J, Eisen SA, True W, Tsuang MT, Meyer JM, Henderson WG: Do genes influence exposure to trauma? a twin study of combat. Am J Med Genet 1993; 48:22-27Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Koenen KC, Harley R, Lyons MJ, Wolfe J, Simpson JC, Goldberg J, Eisen SA, Tsuang MT: A twin registry study of familial and individual risk factors for trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 2002; 190:209-218Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Hettema JM, Neale MC, Kendler KS: A review and meta-analysis of the genetic epidemiology of anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1568-1578Link, Google Scholar

37. Nichols RC, Bilbro WC Jr: The diagnosis of twin zygosity. Acta Genet Med Gemellol 1966; 16:265-275Google Scholar

38. Kasriel J, Eaves L: The zygosity of twins: further evidence on the agreement between diagnosis by blood groups and written questionnaires. J Biosoc Sci 1976; 8:263-266Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Jang KL, Vernon PA, Livesley WJ, Stein MB, Wolf H: Intra- and extra-familial influences on alcohol and drug misuse: a twin study of gene-environment correlation. Addiction 2001; 96:1307-1318Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Stein MB, Walker JR, Hazen AL, Forde DR: Full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder: findings from a community survey. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1114-1119Link, Google Scholar

41. Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K: The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychol Assess 1997; 9:445-451Crossref, Google Scholar

42. Asmundson GJG, Frombach I, McQuaid JR, Pedrelli P, Lenox R, Stein MB: Dimensionality of posttraumatic stress symptoms: a confirmatory factor analysis of DSM-IV symptom clusters and other symptom models. Behav Res Ther 2000; 38:203-214Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. King DW, Leskin GA, King LA, Weathers FW: Confirmatory factor analysis of the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale: evidence for the dimensionality of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Assess 1998; 10:90-96Crossref, Google Scholar

44. McGue M, Bouchard TJ Jr: Adjustment of twin data for the effects of age and sex. Behav Genet 1984; 14:325-343Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Jöreskog K, Sörbom D: PRELIS 2: A Preprocessor for LISREL. Chicago, Scientific Software, 1993Google Scholar

46. Neale M, Boker SM, Xie G, Maes HH: Mx: Statistical Modelling, 5th ed. Richmond, Medical College of Virginia, 1999Google Scholar

47. Neale MC, Cardon LR: Methodology for Genetic Studies of Twins and Families. Dordrecht, Netherlands, Kluwer, 1992 Google Scholar

48. Stein MB, Jang KL, Livesley WJ: Heritability of social-anxiety related concerns and personality characteristics: a twin study. J Nerv Ment Dis 2002; 190:219-224Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Chavira DA, Stein MB, Malcarne VL: Scrutinizing the relationship between shyness and social phobia. J Anxiety Disord (in press)Google Scholar

50. Kendler KS: Twin studies of psychiatric illness: an update. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:1005-1014Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Foley DL, Neale MC, Kendler KS: A longitudinal study of stressful life events assessed at personal interview with an epidemiologic sample of adult twins: the basis of individual variation in event exposure. Psychol Med 1996; 26:1239-1252Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ: A twin study of recent life events and difficulties. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:589-596Google Scholar

53. Kendler KS, Myers J, Prescott CA: The etiology of phobias: an evaluation of the stress-diathesis model. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:242-248Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Wade TD, Kendler KS: The relationship between social support and major depression: cross-sectional, longitudinal, and genetic perspectives. J Nerv Ment Dis 2000; 188:251-258Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. Green BL, Lindy JD: Post-traumatic stress disorder in victims of disasters. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1994; 17:301-309Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. Schnyder U, Moergeli H, Trentz O, Klaghofer R, Buddeberg C: Prediction of psychiatric morbidity in severely injured accident victims at one-year follow-up. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2001; 164:653-656Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Lander ES, Schork NJ: Genetic dissection of complex traits. Science 1994; 265:2037-2048Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58. Risch NJ: Searching for genetic determinants in the new millennium. Nature 2000; 405:847-856Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar