Acute and Chronic Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Motor Vehicle Accident Victims

Abstract

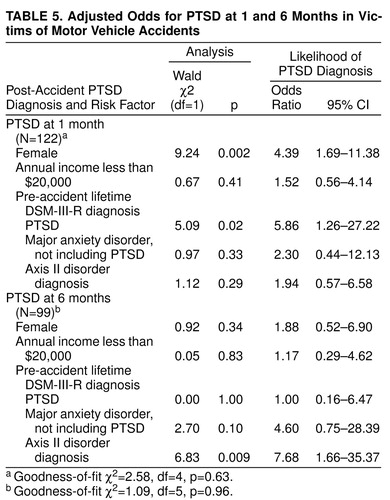

OBJECTIVE: This study reports the rates of acute and chronic posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in a suburban community study group of 122 victims of serious motor vehicle accidents and a comparison group of 42 (who had been involved in minor, non-motor-vehicle accidents) followed over 12 months. METHOD: Motor vehicle accident victims were systematically recruited and examined with comparison subjects at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after the accident. The authors used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R to assess DSM-III-R axis I disorders including PTSD. RESULTS: One month after the accident, 34.4% of the motor vehicle accident victims met criteria for PTSD (versus 2.4% of the comparison subjects). Similarly, at 3 and 6 months, rates of PTSD were higher (25.2% and 18.2%) in the motor vehicle accident victims than in the comparison group. Female victims were 4.64 times more likely than male victims to have PTSD at 1 month. Victims with a history of PTSD were 8.02 times more likely at 1 month and 6.81 times more likely at 3 months to have PTSD than those without a history of PTSD. Having an axis II disorder increased the risk for PTSD at 6 months. After adjustment for a history of PTSD and potentially confounding variables, women were 4.39 times more likely than men to develop PTSD at 1 month but did not have a higher risk for chronic PTSD; at 6 months, those with an axis II disorder were at greater risk of PTSD. CONCLUSIONS: Rates of PTSD are high in victims of serious motor vehicle accidents and remain high 9 months later. Female victims have an increased risk of acute but not chronic PTSD. Individuals with a history of PTSD are at risk of acute and chronic PTSD. An axis II disorder increases the risk for chronic but not acute PTSD.

Motor vehicle accidents are common yet unexpected traumatic events. Their consequences can be chronic, disabling, and catastrophic. In 1992, there were approximately 6 million motor vehicle accidents in the United States, costing an estimated $137 billion (1).

A number of studies (2–9) have suggested the occurrence of psychiatric morbidity in motor vehicle accident victims. However, we are aware of only a few studies that have used standardized interviews to diagnose posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in motor vehicle accident study groups (2, 8–10). The reported rates of PTSD in victims of serious motor vehicle accidents have ranged from 8% (7) to 46% (8). In a cross-sectional study, Blanchard et al. (2) found that a history of trauma or major depression was a significant risk factor for developing PTSD after a serious motor vehicle accident. Inconsistencies across measurement, time elapsed from motor vehicle accident, and the absence of systematic longitudinal follow-up have made it difficult to draw conclusions about the risk of psychiatric morbidity after serious motor vehicle accidents.

DSM-III-R did not distinguish between acute and chronic PTSD. However, because its authors recognized that the chronicity of PTSD is an important issue (11–13), DSM-IV defined chronic PTSD as having symptoms lasting 3 months or longer. Up to 57% of the PTSD sufferers in some populations have had PTSD for more than 1 year (11). It has been estimated that at least one-third of those with PTSD do not recover, regardless of professional interventions (13). Approximately 7.8% of the population has a history of PTSD (13). Lifetime PTSD is more prevalent in women and in those who are separated, divorced, or widowed. Preexisting anxiety or depression, a family history of anxiety, female gender, neuroticism, and early separation have also been associated with a higher risk of chronic PTSD (11).

To our knowledge, there have been no systematic, long-term prospective studies that have used structured clinical interviews to examine motor vehicle accident-related PTSD in the general population. This study reports the rates of acute and chronic (3 and 6 months) PTSD in suburban community study groups consisting of 122 motor vehicle accident victims and 42 comparison subjects followed over 12 months. Although we studied a number of factors pertinent to stress response, here we were most interested in variables of use to clinicians working with motor vehicle accident victims that would guide clinical practice and planning and clarify the selection of 3 or 6 months as the time to diagnose chronic PTSD. We present risk factors for the development of acute and chronic PTSD.

METHOD

Sources of Data and Subjects

The majority of the victims of serious motor vehicle accidents were recruited from the regional trauma center of a major suburban hospital in a large metropolitan area. Twenty-eight percent of the motor vehicle accident victim study group was recruited through local police reports of severe motor vehicle accidents. (Recruits from these sources did not differ on demographic or dependent variables.) Approximately half of the hospital recruits and 25% of the recruits from the police accident records agreed to participate. The recruits and those who refused to participate did not differ demographically except that those who refused were less educated and had a higher average blood alcohol level at the time of the accident than did participants (0.03 versus 0.006) (14). We also recruited a comparison group of 42 subjects who were seen in the hospital emergency room, treated for minor injuries (e.g., cuts, sprains) from non-motor-vehicle accidents, and released. The study group 1 month after the accident consisted of 164 subjects (122 motor vehicle accident victims and 42 comparison subjects); at 6 months, 137 subjects (99 motor vehicle accident victims and 38 comparison subjects); and at 12 months, 120 subjects (86 motor vehicle accident victims and 34 comparison subjects). After completely describing the study to the subjects, we obtained written informed consent.

Recruitment Criteria

The motor vehicle accident victims were drivers or passengers in serious accidents involving another passenger car, motorcycle, or truck within the previous 2 weeks. Potential participants were at least 18 and not more than 65 years of age and resided within a 40-mile radius of the regional trauma center. Two physicians systematically reviewed hospital records and excluded individuals who had head trauma, coma, or organic brain syndrome identified by positive findings on a neurological examination, positive findings on a mental status examination, or positive findings on a CAT scan. Alcohol and drug levels were noted from the patients’ charts.

Comparison group subjects met the same age and location requirements as the motor vehicle accident victims and had not been in a motor vehicle accident in the past 3 years. The mean age at the time of the accident for motor vehicle accident victims was 35.59 years (SD=13.06) and it was 37.16 (SD=13.09) for the comparison group. There were no substantial differences between the motor vehicle accident victims and the comparison group on demographic characteristics (table 1) at any assessment point, on previous history of psychiatric disorder, or on family history of psychiatric illness, depression, or alcohol or drug abuse.

Initial and Follow-Up Evaluations

During the initial contact (14–21 days after the accident), we provided subjects with a description of the study and the responsibilities involved in participation. At 1 month after the accident, we used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R and for DSM-IV (SCIDs) (15, 16) and the SCID PTSD supplement (17) to assess DSM-III-R axis I disorders. The SCIDs and PTSD supplement were conducted (and tape recorded) at the subjects’ homes by one of two senior licensed clinical social workers trained and experienced in the administration of the SCIDs. Half of the SCID audiotapes were reviewed by the senior clinician (R.J.U.) on an ongoing basis to ensure consistent interview procedures and reliability. The average of the kappas for overall symptom agreement between the two interviewers and senior supervisor on PTSD diagnosis and for each of the PTSD symptoms was excellent (kappa>0.95, p<0.001). Kappa values for other diagnoses (including axis II disorders) were similarly high. We resolved diagnostic disagreements by consensus.

The clinician also collected a detailed life history and rated each subject on presence or absence of a probable axis II disorder. For all analyses, axis I disorder diagnoses were coded as present only if all diagnostic criteria were met. Subjects were asked a series of questions about their family history of psychiatric illness. The clinician specifically probed by using clinical and lay language for a family history of alcohol abuse, drug abuse, depression, or other psychiatric illness.

In order to assess previous trauma, subjects were asked if they had experienced any events outside the range of usual human experience before their accident (childhood or adult) by using the DSM-III-R stressor criterion definition. Subjects were asked specifically about major earthquakes or floods, serious accidents, fires, physical assault, rape, seeing another person being killed or dead, war and combat experience, and any other type of disaster. The interviewer both probed and inquired specifically about different periods of the subject’s life. Positive answers were recorded as to type of event and time of exposure.

We assessed accident-related injuries (0=no, 1=yes) and severity of injury (0=none, 1=minor, 2=major): injury to self, head injury (minor), passenger injury, and injury to occupants of the other vehicle. At 6 and 12 months after the accident, we assessed current psychiatric diagnosis and psychiatric diagnosis for the intervening periods (3 and 9 months, respectively).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was established at 1% for all analyses to protect against overinterpretation of findings. We report p≤0.05 as suggestive and all other findings as not statistically significant. Comparisons between motor vehicle accident victims and comparison subjects used chi-square analyses, Fisher’s tests, and t tests, as appropriate. Potential risk factors for PTSD after motor vehicle accidents were evaluated by univariable logistic regressions and chi-square analyses to examine the predictors of lifetime PTSD (previous to the motor vehicle accident), acute PTSD (1 month after the accident), and chronic PTSD (3 months and 6 months after the accident). Analyses for lifetime PTSD (before the motor vehicle accident or, for the comparison group, before the minor accident) using both study groups combined (motor vehicle accident victims and comparison subjects) were comparable with analyses for the motor vehicle accident victims group alone.

Odds ratio was defined as the likelihood of developing PTSD for individuals with a risk factor versus those without the risk factor. The estimate of the odds ratio and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were reported. The Wald test was used to decide if there was any difference between the odds of developing PTSD for individuals with a risk factor and those without the risk factor (if the odds ratio is other than 1). To ensure stability of findings, analyses were repeated by using list-wise deletion to include only subjects present at 1, 3, and 6 months after the accident. Goodness-of-fit chi-square analyses assessed how well the model predicted the data (18). Statistical analysis software (SAS) (19) was used.

RESULTS

Rates of PTSD and Other Psychiatric Disorders After Motor Vehicle Accidents

There were no significant differences between motor vehicle accident victims and comparison subjects on lifetime (pre-accident) PTSD (table 2). Victims assessed at 1 month after the motor vehicle accident had significantly higher rates of PTSD than did comparison subjects. Similarly, at 3 and 6 months after the accident, the victims had significantly higher rates of PTSD. In order to assess any effect of dropouts from the study, we examined the rates of PTSD in motor vehicle accident victims, looking only at subjects completing the study. Rates were nearly identical to those reported in table 2. Although the majority of motor vehicle accident victims with PTSD were first diagnosed 1 month after the accident, two accident victims were diagnosed with PTSD for the first time 3 months after the accident. There were no significant differences between motor vehicle accident victims and comparison subjects in rates of major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, or panic disorder at any assessment time after the accident.

We assessed the rates of exposure to traumatic events (excluding the target accident) over the follow-up period of the study. Of the total study group (motor vehicle accident victims and comparison subjects combined), approximately seven of 100 individuals (6.8%) were exposed annually to a traumatic event that met DSM-III-R criteria for PTSD (eight events over 117 person-years). The rates were similar for the motor vehicle accident victims and the comparison subjects (7.1% versus 6.1%, respectively). No demographic variables predicted exposure to a traumatic event.

Risk Factors for PTSD in Motor Vehicle Accident Victims

Demographics

The risk for PTSD 1 month after a motor vehicle accident was 4.64 times greater for women (51.7%) than for men (18.7%) (table 3) and 3.85 times greater for nonwhites (58.6%) than for whites (26.9%). The risk for PTSD at 3 months was 4.06 times greater for nonwhites (50.0%) than for whites (19.8%). Although those reporting an annual income of less than $20,000 (39.3%) were at 2.94 times greater risk for PTSD 3 months after the accident than those with incomes of $20,000 or more (18.0%), this difference was not significant. At 6 months after the accident, no demographic factors showed a significantly higher risk for PTSD; however, there was a suggestion that nonwhites and those with high school or less education were at greater risk for PTSD.

To examine each demographic risk factor by controlling for all other demographic characteristics, we used multivariable logistic regression. For each PTSD outcome measure (i.e., 1, 3, and 6 months after the motor vehicle accident), all demographic characteristic variables were entered simultaneously. All models showed good fit. At 1 month after the accident, with all other demographic characteristics controlled, female victims and nonwhites continued to show a substantially higher risk for developing PTSD. Female victims had a risk of developing PTSD that was 6.53 times greater than that for male victims (Wald χ2=12.60, df=6, p=0.002, 95% CI=2.32–18.39), and nonwhites were 6.66 times more likely to develop PTSD 1 month after the accident than were whites (Wald χ2=9.26, df=6, p=0.002, 95% CI=1.96–22.57). Goodness-of-fit χ2=5.26 (df=8, p=0.73). At 3 and 6 months, with all other demographic variables controlled, only race carried a significant risk, with nonwhites at 9.08 times greater risk for PTSD at 3 months than whites (Wald χ2=9.28, df=6, p=0.002, 95% CI=2.20–37.50) and at 7.28 times greater risk for PTSD at 6 months (Wald χ2=6.96, df=6, p=0.008, 95% CI=1.67–31.83). Each of the models showed good fit: goodness-of-fit χ2=10.13, df=8, p=0.26, and χ2=11.3, df=8, p=0.19, at 3 and 6 months, respectively.

Family history of psychiatric disorder

We examined the risk for PTSD for a family history of alcohol abuse, drug abuse, substance abuse of any kind (either alcohol or drug abuse), depression, other psychiatric disorder, and any psychiatric disorder. No family history variables were associated with a greater risk of PTSD at 1, 3, or 6 months.

Accident-related injury

None of the injury-related variables were significantly associated with a higher risk for PTSD at 1, 3, or 6 months. However, several were suggestive. Of those victims reporting that a passenger had been injured, 50.0% (N=18) had PTSD at 1 month compared to 27.4% (N=23) of those who reported no injured passengers (Wald χ2=5.56, df=1, p=0.02, odds ratio=2.65, 95% CI=1.18–5.96). Similarly, of those who reported that the passenger had a major injury, 53.8% (N=7) had PTSD at 1 month; for a minor injury, 47.8% (N=11) had PTSD at 1 month; and for no injury, 27.4% (N=23) had PTSD at 1 month (Wald χ2=2.78, df=1, p=0.02, odds ratio=1.90, 95% CI=1.10–3.29). Of those who reported injuries from the accident, 28.7% (N=25) had PTSD at 3 months, whereas none of those who reported no injuries (N=11) had PTSD at 3 months (χ2=4.24, df=1, p=0.04). Odds ratio could not be calculated for self-injury at 3 and 6 months because there were no uninjured subjects in the PTSD group.

Previous trauma

Of the motor vehicle accident victims, 52 (42.6%) reported having experienced a traumatic event sometime before the accident. (In the comparison group, 44.7% reported a traumatic event before the accident.) History of a previous traumatic event was not related to sex, race, marital status, education, income, or age variables. There was no significant relationship between previous trauma exposure and PTSD at 1, 3, or 6 months.

Diagnosis of psychiatric disorder before accident

Individuals with a diagnosis of PTSD before the motor vehicle accident (N=13) were 8.02 times more likely to have PTSD at 1 month after the accident than were those without a previous diagnosis (table 4). Similarly, those with any anxiety disorder, including PTSD (N=29), were at a higher risk for PTSD at 1 month than those without an anxiety disorder. Although the data did not meet the p≤0.01 significance level, they suggested a higher risk for PTSD in those with a lifetime diagnosis of a major anxiety disorder not including PTSD (i.e., generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, agoraphobia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder) (N=20) or major depression (N=25). At 3 months, those with a lifetime diagnosis of PTSD, a major anxiety disorder not including PTSD, or a probable axis II disorder diagnosis (N=17) were at a higher risk for PTSD.

A history of a major anxiety disorder not including PTSD (N=10) and a probable axis II disorder diagnosis (N=17) significantly increased the risk for PTSD 6 months after the accident.

Adjusted risk factors for PTSD at 1, 3, and 6 months after the motor vehicle accident

We were particularly interested in the contributions of sex and previous PTSD diagnosis to the risk for acute and chronic PTSD. Because women have been reported as having greater lifetime rates of PTSD, we thought these findings might be confounded. Therefore, we used multivariable logistic regression to determine the effect of each risk factor by controlling for all others. Because of their potential confounds with PTSD, our first regression with sex and lifetime PTSD included demographic characteristics (race, education, and income to control for socioeconomic status), lifetime major anxiety disorder diagnoses not including PTSD (20), and probable axis II disorder diagnosis (21). In order to examine a more parsimonious model, we subsequently eliminated race and education and retained income as an overall measure of socioeconomic status. The results of the models predicting PTSD at 1 and 6 months are shown in table 5. Women continued to show a significantly higher risk for PTSD at 1 month than men, and subjects with an axis II disorder diagnosis were at greater risk for PTSD at 6 months than those without. At 3 months, no variables were significant.

In order to address race more specifically, it was then added to the model. The new models were similar to the previous one, with race a significant predictor of PTSD at 1 month (Wald χ2=7.50, df=1, p=0.006, odds ratio=5.38, 95% CI=1.61–17.90), 3 months (Wald χ2=8.23, df=1, p=0.004, odds ratio=7.64, 95% CI=1.90–30.62), and 6 months (Wald χ2=7.12, df=1, p=0.008, odds ratio=8.15, 95% CI=1.75–38.01).

DISCUSSION

Motor vehicle accidents are perhaps the most common trauma experienced by individuals and perhaps the most common cause of PTSD (12, 20–22). While several studies have documented the relationship between motor vehicle accidents and PTSD, methodological inconsistencies have limited systematic comparisons and generalization. Small group size, use of clinical cross-sectional study groups, lack of comparison groups, measurement validity and inconsistencies, and lack of clear delineation between outcomes measured (symptoms of PTSD versus clinical diagnosis of PTSD) have affected previous studies. This study remedies a number of these methodological problems by using a more substantial, well-defined study group, followed longitudinally with reliable and valid diagnostic measures of PTSD. Although our study group is more substantial than those of some of the previous studies, replication with a larger study group size is recommended.

The results of our study indicate that PTSD is a common outcome after a serious motor vehicle accident. Interestingly, no other psychiatric disorders showed higher rates of occurrence after the motor vehicle accident. The rate of PTSD was 34.4% 1 month after the motor vehicle accident and was still high (17.6%) 9 months after the accident. These results clarify and expand on the findings of previous studies (2, 6, 8, 23). A much lower rate (11.5%) was found in a study group of 1,000 adults exposed to a motor vehicle accident serious enough to cause injury to one or more passengers (22). However, that study looked retrospectively over the last year, used a measure of PTSD that was not clinician based, and did not differentiate between acute and chronic PTSD. Our results are more similar to those of Blanchard et al. (2), who found that 39.2% of the individuals who sought motor vehicle accident-related medical assistance in a university clinic met DSM-III-R criteria for PTSD at sometime 1 to 4 months after the accident (or after discharge from the hospital). However, Blanchard et al.’s study combined early- and delayed-onset PTSD (including cases with onset 1–4 months after the accident). If we added delayed-onset PTSD, our rate would be 36.1%.

In our study, 25.2% of the victims of severe motor vehicle accidents met DSM-IV criteria for chronic PTSD (i.e., persisting for 3 months). Approximately one-quarter of those with PTSD at 1 month recovered by 3 months, and another quarter recovered between 3 and 6 months. Thus, nearly half (47.1%) recovered by 6 months. The recovery rate slowed greatly after 6 months, with only 22.5% recovery between 6 and 12 months after the accident. Breslau and Davis (11), measuring lifetime PTSD after any traumatic event in a large urban study group, found that 23.6% of those exposed to trauma met criteria for PTSD. More than three-quarters of those who developed PTSD had symptoms that persisted for 6 months, and slightly more than half had symptoms persisting for more than 1 year. Kessler et al. (13), using lifetime PTSD diagnoses from any cause, found substantially longer median times to remission (36–64 months) than had Breslau and Davis. The recovery rates we found suggest that after motor vehicle accidents, chronic PTSD may more accurately be diagnosed at 6 months than at 3 months, as proposed by DSM-IV. The factors responsible for recovery from acute PTSD, evidenced by the decrease in rate from 1 month (34.4%) to 12 months (14.1%) after the accident, require further study. It is unlikely that this decrease is caused by dropouts because there were no differences in demographic characteristics or PTSD rates between dropouts and those who were included in the follow-up. The role of natural debriefing—the normally occurring discussion about the motor vehicle accident with close friends and relatives—as well as obtaining instrumental support to manage the effects of the motor vehicle accident should be examined as contributors to the normal digesting and metabolizing of acute PTSD symptoms.

It is important to note that previous trauma was not a risk factor for motor vehicle accident-related PTSD. However, previous PTSD was. As suggested by the “kindling” model of PTSD (24), this may indicate that it is not the previous traumatic event but the PTSD-related alterations in brain function that increase the risk for future PTSD.

Our finding that women have nearly a five times greater risk for motor vehicle accident-related PTSD, but not a greater risk for chronic PTSD, is an important clarification to the literature. Importantly, this remains true after controlling for lifetime PTSD (before the accident). Previous studies of motor vehicle accident-related PTSD (2) have found that female victims were more likely than male victims to develop PTSD after a motor vehicle accident, but no data have separated acute from chronic PTSD. The reason for these differences in the risk for acute and chronic PTSD in women is not clear and requires further study. Studies of mixed traumatic events (11, 13) have found women more than twice as likely as men to have lifetime PTSD, from any cause, and also more likely to have chronic PTSD, even after adjusting for other factors. Weisaeth (25) found that differences between rates of PTSD in men and women following a paint factory explosion were not present when he controlled for previous trauma training. Thus, potential differences in neurobiology, stress hormones, types of trauma exposure, personality factors, and training for traumatic exposure may be important.

Our data suggest that those with a history of a major anxiety disorder are also at more than five times the risk of both acute and chronic PTSD. In addition, a history of major depression may be associated more with a higher risk of developing acute but not chronic motor vehicle accident-related PTSD. These results clarify previous reports that more PTSD subjects have had a previous depressive episode (59.0%), panic disorder (11.3%), or any anxiety disorder (29.0%) (2). Our finding that a personality disorder diagnosis (axis II disorder) predicts chronic PTSD, after controlling for relevant variables, is provocative. The presence of a personality disorder may decrease some of the natural curative factors hypothesized as important to recovery from PTSD—e.g., social supports, natural debriefing opportunities. Further study by using more systematic measures of axis II disorders is indicated.

The high rate of PTSD 9 months after a motor vehicle accident indicates the potential chronicity of serious motor vehicle accident-related PTSD. It is particularly important to study differences between acute and chronic PTSD in both women and men. Given that PTSD can become chronic for some individuals, a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying recovery or the development of chronic PTSD is needed.

Received Sept. 19, 1997; revisions received March 9, July 28, and Oct. 16, 1998; accepted Nov. 19, 1998. From the Departments of Psychiatry and Medical Psychology, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, F. Edward Hébert School of Medicine; and the Department of Behavioral Medicine and Oncology, University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, Pittsburgh, Pa. Address reprint requests to Dr. Ursano, Department of Psychiatry, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, 4301 Jones Bridge Rd., Bethesda, MD 20814-4799. Supported by NIMH grant MH-40106. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors’ institutions or the U.S. Department of Defense.

|

|

|

|

|

1. US Department of Transportation: Traffic Safety Facts. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1992Google Scholar

2. Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ, Taylor AE, Loos W: Psychiatric morbidity associated with motor vehicle accidents. J Nerv Ment Dis 1995; 183:495–504Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Bryant RA, Harvey AG: Initial posttraumatic stress responses following motor vehicle accidents. J Trauma Stress 1996; 9:223–234Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Burstein A: Posttraumatic stress disorder in victims of motor vehicle accidents. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1989; 40:295–297Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Epstein R: Avoidant symptoms cloaking the diagnosis of PTSD in patients with severe accidental injury. J Trauma Stress 1993; 4:451–458Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Hickling EJ, Blanchard EB: Post-traumatic stress disorder and motor vehicle accidents. J Anxiety Disord 1992; 6:283–304Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Malt UF, Blikra G: Psychosocial consequences of road accidents. Eur Psychiatry 1993; 8:227–228Google Scholar

8. Mayou R, Bryand B, Duthie R: Psychiatric consequences of road traffic accidents. BMJ 1993; 307:647–651Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ, Taylor AE, Loos W, Gerardi RJ: The psychological morbidity associated with motor vehicle accidents. Behav Res Ther 1994; 31:283–290Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Green MM, McFarlane AC, Hunter CE, Griggs WM: Undiagnosed posttraumatic stress disorder following motor vehicle accidents. Med J Aust 1993; 159:529–534Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Breslau N, Davis GC: Posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults: risk factors for chronicity. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:671–675Link, Google Scholar

12. Davidson JRT, Fairbank JA: The epidemiology of PTSD, in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: DSM-IV and Beyond. Edited by Davidson JRT, Foa EB. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1992, pp 147–172Google Scholar

13. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:1048–1060Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Delahanty DL, Herberman HB, Craig KJ, Hayward MC, Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ, Baum A: Acute and chronic distress and posttraumatic stress disorder as a function of responsibility for serious motor vehicle accidents. J Clin Consult Psychol 1997; 656:560–567Crossref, Google Scholar

15. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P), Version 2. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

16. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Non-Patient Edition (SCID-NP), Version 1.0. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

17. Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Jordan BK, Hough RL, Marmar CR, Weiss DS: Assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: prospects and pitfalls from recent studies of Vietnam veterans. Psychol Assessment 1991; 3:547–560Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Hosmer D, Lemeshow S: Goodness-of-fit tests for the multiple logistic regression model. Communication Statistics, Part A: Theor Meth 1980; A10:1043–1069Google Scholar

19. SAS Procedures Guide, Version 6.08. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1990Google Scholar

20. Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson E: Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in a urban population of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:216–222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Paris J: Does childhood trauma cause personality disorders in adults? Can J Psychiatry 1998; 43:148–153Google Scholar

22. Norris FH: Epidemiology of trauma: frequency and impact of different potentially traumatic events on different demographic groups. J Consult Clin Psychol 1992; 60:409–418Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Brom D, Kleber RJ, Hoffman MC: Victims of traffic accidents: incidence and prevention of posttraumatic stress disorders. J Clin Psychol 1993; 49:131–140Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Post R: Stress, sensitization, kindling, and conditioning. Behav Brain Sci 1985; 8:372–373Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Weisaeth L: Psychological and psychiatric aspects of technological disasters, in Individual and Community Responses to Trauma and Disaster: The Structure of Human Chaos. Edited by Ursano RJ, McCaughey BG, Fullerton CS. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, 1994, pp 72–102Google Scholar