Emily Dickinson Revisited: A Study of Periodicity in Her Work

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Emily Dickinson, arguably one of America’s foremost poets, is characterized by critics as able to capture extreme emotional states in her greatest work. Recent dating of her poems offers the periodicity of her writing as a behavior that can be examined for patterns of affective illness that may relate to these states. METHOD: The bulk of Dickinson’s work was written during a clearly defined 8-year period when she was age 28–35. Poems written during that period, 1858–1865, were grouped by year and examined for annual and seasonal distribution. RESULTS: Her 8-year period of productivity was marked by two 4-year phases. The first shows a seasonal pattern characterized by greater creative output in spring and summer and a lesser output during the fall and winter. This pattern was interrupted by an emotional crisis that marked the beginning of the second phase, a 4-year sustained period of greatly heightened productivity and the emergence of a revolutionary poetic style. CONCLUSIONS: These data, supported by excerpts from letters to friends during this period of Dickinson’s life, demonstrate seasonal changes in mood during the first four years of major productivity, followed by a sustained elevation of creative energy, mood, and cognition during the second. They suggest, as supported by family history, a bipolar pattern previously described in creative artists.

Emily Dickinson is one of America’s most celebrated poets, although she was virtually unknown during her lifetime. Since the 1950s, when her collected poems and letters were first published, considerable speculation has focused on her state of mind (1). An era of psychological “pathologizing” of her life has given way to a current period of “normalizing” by Dickinson scholars, e.g., in suggesting that her housebound adult life was a conscious decision in the service of her work (2, 3). Nevertheless, Dickinson herself remains largely a mystery, as there are little or no objective data available to help understand the extremes of emotion she was able to capture in her extraordinary poetry.

A recent study (4), using Dickinson’s collected letters rather than her poems as an autobiographical source, confirms a sudden, spontaneous anxiety attack at age 24, the self-described symptoms of which clearly meet DSM-IV criteria for a panic attack, followed by the rapid onset of agoraphobia during that same year, again described in her letters. Speculation from this data has suggested ways in which the specific panic symptoms described in her letters may have been transformed into poetic metaphor.

But this can only partially explain Dickinson’s state of mind. It does not address her special capacity to capture what has been called by Dickinson critics the “depressive experience” and transform it into metaphor, a phenomenon over which they have puzzled for decades. Consider the opening and closing verses from one of Emily Dickinson’s best known poems:

There’s a certain Slant of light, Winter Afternoons— That oppresses, like the Heft Of Cathedral Tunes—… When it comes, the Landscape listens— Shadows—hold their breath— When it goes, ’tis like the Distance On the look of Death—(5, F320)

Contemporary Dickinson biographer Paula Bennett observed that the reason for this poem’s popularity does not lie in technique alone but in our becoming a partner in what she calls the poet’s own “depression”; i.e., the speaker’s mood “takes over from the light and is generalized to the entire landscape” (6, p. 117). Other Dickinson scholars have commented on “the winter within her,” because many of her best poems skirt the subject of suicide (7).

Perhaps the other half of the puzzle, then, can be sought in the well-established connection between panic and affective disorder (8–11). Again, Dickinson’s letters offer a clear clinical picture, one painted by the poet herself (12). Born in 1830, she described herself during adolescence as suffering from a “fixed melancholy” after the death of a friend (12, L11). Its persistence caused her to withdraw from school the following year: “I left school and did nothing for some time excepting to ride and roam in the fields” (L13). Soon she came to associate what she called her “down-spirited” mood (L81) with the season of the year (L13) and her preoccupation with the march of the seasons with death itself (13).

This early autobiographical picture, in the context of a several times greater rate of affective disorder in artists than in the general population (14–17), suggests that it would be reasonable to examine Emily Dickinson’s life and work further for depression and its possible relationship to her artistic creativity. This study will use the chronology of Dickinson’s poems as a database. It will examine the periodicity of her work both by year and season, searching for possible associations between artistic productivity and changes in mood during the most productive period of her life.

Method

After her death in 1886, Dickinson’s lifetime work, nearly 1,800 poems, undated and in various manuscript states, was discovered in her bedroom. The originals had remained in her possession, although she had made copies over the years to send to friends. Although selected poems from this find were subsequently edited and published by friends and family members, the first collected edition of the whole of her work with an attempt at sequencing was not published until the 1950s (18). And it was not until 1998 that The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Variorum Edition, edited by R.W. Franklin (5), established the chronology of the poems with some precision. Franklin sequenced the poems according to when they appeared to have been first written, using characteristic and frequent changes in handwriting, spelling, grammar, and writing materials. The dating was done conservatively, by year, by season, and, where possible, by month. When a poem was dated “early” or “late” in the year, it was listed as being written in the first or last 3 months of that year (personal communication, R.W. Franklin). Poems were then counted and grouped by year and season by the author. When no season could be assigned or the time was too broadly identified, e.g., first half or second half of the year, poems were excluded from seasonal data but included in annual data.

Results

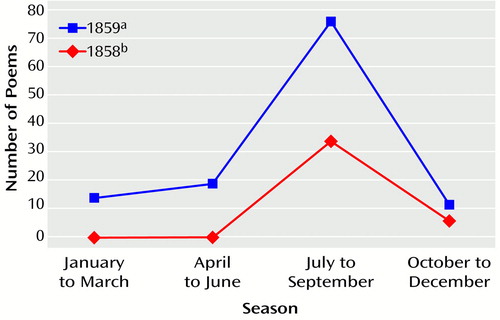

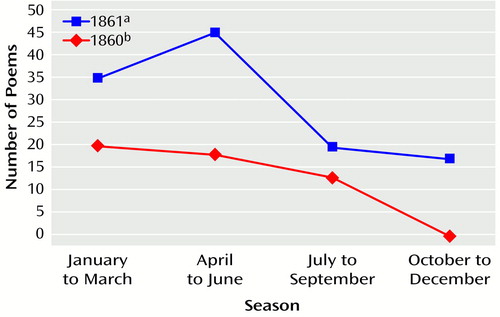

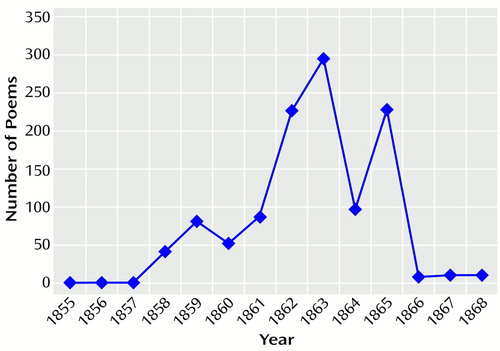

Figure 1 and Figure 2 represent a seasonal distribution of the poetry written during the first 4 years of Emily Dickinson’s serious writing career, 1858–1861 (no more than one poem was identified as written in any given year before 1858). Figure 3 is a graphic representation of her 8 most productive years, 1858–1865, when she was age 28–35 (5).

The first 4-year period, 1858–1861, is considered the period when “the flood of her talent is rising” (12, p. 332). As shown in Figure 1, her productivity in 1858 and 1859 formed a distinct seasonal pattern, with summer accounting for three times the productivity of fall and winter combined. Figure 2 illustrates a changing pattern. Although slightly more poems were written in the winter months of 1860 than during any other season that year, during the spring and summer of 1860 combined, she produced more poetry than during the combined fall and winter of 1860. The 1861 seasonal pattern was interrupted by an emotional crisis to be discussed.

As shown in Figure 3, the second 4-year period of intensive writing, 1862–1865, presents a further major increase in her productivity. This surge was sustained, except for a dip in 1864 when Dickinson spent over one-half the year in Boston for a medical problem, thought to have been an eye disorder. Her writing during that time was restricted by her doctor. After another peak in 1865, her productivity dropped off to a steady handful of poems each year until her death in 1886.

Discussion

The most productive years of Emily Dickinson’s writing career seem to divide themselves into two 4-year blocks. The first was marked by a seasonal pattern. Of course, her preference for summer is well-known. Summer is mentioned over five times more than any other season throughout her collected poems (19). And although the long, cold New England winters themselves may have influenced her productivity, the Dickinson house, including the bedroom where she did much of her writing at night (personal communication, Polly Longsworth, Ph.D.), was well supplied with wood-burning stoves and whale-oil lamps. Thus, her decline in productivity during the winter months seems more a reaction to the season than to the weather or the lack of daylight by which to work. Wintertime was accompanied by thoughts of death. There is no question that Emily Dickinson suffered painful losses, the deaths of family and friends whom she mourned in letter and verse. But her periods of grief appear prolonged and seasonally weighted toward the winter months. For example, a November 1858 letter to a friend stated, “I thought perhaps that you were dead.…Who is alive? The woods are dead” (12, L195). Even the end of summer marked the anticipation of winter—and of death as well. A September 1859 letter noted: “Indeed, this world is short, and I wish, until I tremble, to touch the ones I love before the hills are red—are grey—are white…” (L207).

The year 1860 continued with a seasonal pattern of productivity but to a lesser extent than during 1858 and 1859. The following year, 1861, seemed to anticipate the seasonal pattern once again. Indeed, the dreaded onset of winter was handled humorously in August of that year. Dickinson wrote: “I shall have no winter this year…I thought it best to omit the season…” (L235). But suddenly the seasonal pattern of the previous 3 years was disrupted with the onset of a severe emotional crisis in the fall of 1861 (to be discussed).

What can we make of the seasonal pattern in Dickinson’s early work? On one hand, it reflects the uncommon sensitivity to seasonal fluctuations found in the work of many artists (16, 20). In Emily Dickinson’s case, it is possible that it may also reflect a recurrence of the melancholia she described as an adolescent, now marked by a seasonal pattern, with recurrence during the winter months.

But what could account for the sudden surge in productivity beginning in 1861–1862, a surge that overrode the previous seasonal pattern? In April 1862, Dickinson wrote her advisor, Thomas Higginson, of a “Terror—since September [1861]—I could tell to none—and so I sing, as the Boy does by the Burying Ground—because I am afraid—” (12, L261) (“sing” was a word Dickinson used to refer to writing poetry). There was no further direct reference to “the Terror” in her letters, although she received a note of concern from a clergyman friend that read, “I am distressed beyond measure at your note, received this moment—I can only imagine the affliction which has befallen, or is now befalling you” (L248A). The rest of that year, 1862, seemed a blur to Emily Dickinson, and although she composed 277 poems in 1862 alone, she wrote a half-humorous but puzzled line to a friend in December: “I don’t remember ‘May.’ Is that the one that stands next to April?” (L245).

A characteristic overlap between spring or autumn creative peaks and the onset of manic periods has been described in many artists (16). Perhaps the crisis Emily Dickinson described in 1861–1862 signaled a switch in polarity of mood. Such speculation is supported by the fact is that Dickinson’s productivity rose dramatically in 1861 and 1862; i.e., during the very time she was experiencing “the Terror,” Dickinson produced a flood of poems. This second 4-year period of productivity, 1862–1865, accounted for far more poems than any other period in her life. Indeed, she seemed so overwhelmed by this new, sustained burst of energy that she completely discounted those earlier (1858–1861) productive years. In the April 1862 letter to Higginson referred to previously, she described her career as a poet: “I made no verse—but—one or two—until this winter” (12, L261). She seemed to date her own creativity to the time of “the Terror.”

“The Terror” marked the onset of a prolonged surge of creative energy and the beginning of the most productive period of her life, 1862–1865. New ideas followed one another with extraordinary rapidity. Those 4 years account for over one-half of the almost 1,800 poems written during her 33-year writing career. The change in mood can be found in her letters, formerly one of gloom, to one of elation. There was a cognitive change as well, as she wrote of her work, “My business is to love………My business is to sing.”(L269).

Critics have long puzzled over the marked alteration in poetic form in Dickinson’s work after 1860. It has been described by one of them as the sudden development of several simultaneously expanding metaphors, creating an experience that required a new kind of reading (21). There had been not just a quantitative change in her writing but a qualitative one as well. Dickinson herself recognized this new, expansive creative form. Her almost constant stream of ideas, combined with a newfound energy, marked a new creative period. But she also saw it as a kind of fragmentation in a letter to Higginson: “I…cannot rule myself, and when I try to organize—my little Force explodes—and leaves me bare and charred—” (12, L271). For in addition to the marked changes in mood and cognition, her behavior had changed as well. The meticulous binding of poems into themes, or “fascicles,” by hand from 1858 onward had become disorderly (5). She recognized the process, apologizing to her preceptor Higginson for the disorganization, sending him more poems to critique and adding, “Are these more orderly?” (12, L271).

Kay Redfield Jamison, in her book Touched With Fire, listed Emily Dickinson among the artists with probable major depression or manic depressive illness but offers no supporting data (16). This study of the periodicity in Dickinson’s writing career offers data suggestive of affective illness during her productive years. First of all, Dickinson described herself as suffering from a “fixed melancholy” in adolescence, during which she dropped out of school (12, L11). Her own beloved lexicon, Webster’s An American Dictionary of the English Language(22), described melancholy, when prolonged, as a “disease.” It seems possible, considering recent research studies of community populations (23) that have identified high recurrence rates of affective illness in adolescents with vulnerabilities such as female gender and depressive cognitions, that this melancholy may have recurred in seasonal form at the beginning of Dickinson’s most productive years. These years divide in two, the first 4 generally characterized by an increase in productivity in the summer and a reduced poetic output and pessimistic mood in the winter. This pattern was interrupted by an emotional crisis that she described as “a Terror,” signaling a second 4-year phase of expansive creativity, a fever to write, and an intensity clearly dating from the time of “the Terror.”

Why did Dickinson characterize the onset of this creative burst as “a Terror”? Fearfulness has been described as one way in which artists experience the arousal of creativity (16). And although the word “terror” may not typify the onset of mania or hypomania today, the same biologically determined process may have been experienced differently in different historical periods. In any case, the 8-year productive period described previously is not inconsistent with the symptom profile of bipolar II affective disorder, “the Terror” perhaps signaling a sudden frightening change in polarity.

Emily Dickinson has long been considered a complex figure by her biographers, with many contrasting, if not contradictory, sides to her personality: withdrawn and reclusive on one hand; assertive and ebullient on the other. Another possible explanation is that she may have suffered from a recurrent affective disorder, with the well-known emotional and cognitive fluctuations that are part of its course. Such speculation addresses the mystery of her poetic drive; i.e., critics have wondered why the bulk of Dickinson’s work was produced in a period of a few short years, with the drive suddenly coming to an end (24).

Emily Dickinson’s physician, without knowing it, may have helped solve the mystery of her mental state some years later, when Dickinson was 53: “The Physician says I have ‘Nervous Prostration,’” she wrote a friend. “Possibly I have—I do not know the Names of Sickness” (12, L873). Nervous prostration was a condition that was by then subsumed under the diagnosis of neurasthenia, an illness characterized by anxiety and depression (25). Emily Dickinson’s “Nervous Prostration” might have been the end result not only of her earlier documented panic and agoraphobia but of a possible bipolar disorder as well. Recent evidence from genetic research (9, 10) has suggested that panic may indeed be a bipolar marker. But it was not until many years later that Kraepelin described manic and depressive mood swings and separated them from dementia praecox. Thus, Dickinson’s physician diagnosed nervous prostration, then a catchall for symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Jamison, in her investigation of the overlapping of depressive, manic, and creative states, has found high rates of bipolar disorder among artists, especially poets (16). Andreasen (26) found these creative abilities and mood disorders to aggregate in certain families. What is the evidence of such a pattern in the Dickinson family? There is some. The behavior of Emily Dickinson’s paternal grandfather, Samuel Fowler Dickinson, the black sheep of the family, has confounded Dickinson biographers for years. A founder of Amherst College and an eminent civic leader, he was described by the president of Amherst College as “one of the most industrious and persevering men that I ever saw” (24, p. 35). But his periods of energy and enthusiasm appeared to alternate with depression. First accumulating then losing the family fortune, exiled from Amherst to the Midwest, he was remembered by his daughter: “It seems as if his depression of spirits caused his sickness which terminated his life” (24, p. 38). The eminent Dickinson biographer Richard Sewall noted this “breakdown” and suggested that Squire Fowler exhibited traits that became more extreme in succeeding generations (24, p. 38). Samuel Fowler Dickinson’s own references to his mood swings can be found in letters before and after his graduation from Dartmouth College in 1795. Needing only 4 hours’ sleep at night, he characterized himself as having “burned out my candle and made the clock strike thirteen” on one hand and at other times complaining of melancholy and “general debility pervading my constitution” on the other (27, MS797301).

Conclusions

The limitations of this study are well recognized. Diagnostic impression without examination is conjecture at best. Furthermore, the sample of poems available may be incomplete; i.e., it conceivable that others were written and lost or destroyed and were not included in those found in Dickinson’s room after her death. And although the chronology of all Dickinson’s poems established by the recent Franklin Variorum Edition is more precise by time of year than ever before, it remains an educated judgment. Nevertheless, to our knowledge, this study is the first quantitative data-based assessment of Dickinson’s work with use of the periodicity of her poetry writing as a measure. Its primary purpose was to discover new information about Emily Dickinson rather than explain her.

If the data presented here offer a new interpretation of Emily Dickinson’s career and a further glimpse into her pattern of creative productivity, they cannot explain the phenomenon of her imagination. For if Emily Dickinson was indeed the victim of the well-known Faustian bargain between affective illness and creative genius, it was her courage and imagination that enabled her to rise above the former and use the latter to transform powerful affects into metaphor. Her work frames complex emotional extremes with words that have a life of their own, words that have moved generations of Americans and others throughout the world. Perhaps Emily Dickinson had some insight into the secret of her own creative genius when she penned the lines beginning

The Brain—is wider than the Sky… (5, F578)

Received July 26, 2000; revision received Dec. 8, 2000; accepted Dec. 19, 2000. From the Department of Psychiatry, University of Hawaii School of Medicine. Address reprint requests to Dr. McDermott, P.O. Box 6840, Kamuela, HI 96743; [email protected] (e-mail). The author thanks Robert Michels, M.D., and David Porter, Ph.D., for suggesting this study, R.W. Franklin, Ph.D., for further interpretive dating of the poetry, and Polly Longsworth, Ph.D., for help with Dickinson’s writing habits. Poems F320 and F578 reprinted by permission of the publishers and the Trustees of Amherst College from The Poems of Emily Dickinson, Ralph W. Franklin, ed., Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Copyright © 1998 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Copyright © 1951, 1955, 1979 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Figure 1. Number of Poems Written by Emily Dickinson per Season During 1859 and 1858

aOne could not be dated by month.

bTwo could not be dated by month.

Figure 2. Number of Poems Written by Emily Dickinson per Season During 1861 and 1860

aTwenty-two could not be dated by month.

bThree could not be dated by month.

Figure 3. Number of Poems Written by Emily Dickinson per Year From 1855 to 1868

1. Cody J: After Great Pain: The Inner Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1971Google Scholar

2. Rich A: Vesuvius at home: the power of Emily Dickinson. Parnassus Poetry in Review 1976; 5:51–52Google Scholar

3. Smith MN: Rowing in Eden: Re-Reading Emily Dickinson. Austin, University of Texas, 1992Google Scholar

4. McDermott JF: Emily Dickinson’s nervous prostration and its possible relationship to her work. Emily Dickinson J 2000; 9:71–86Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Franklin RW (ed): The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Variorum Edition, vols 1–3. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1998Google Scholar

6. Bennett P: Emily Dickinson: Woman Poet. Iowa City, University of Iowa Press, 1990Google Scholar

7. Porter D: Dickinson: The Modern Idiom. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1981Google Scholar

8. Gorman JM, Kent JM, Sullivan GM, Coplan JD: Neuroanatomical hypothesis of panic disorder, revised. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:493–505Link, Google Scholar

9. MacKinnon DF, McMahon FJ, Simpson SG, McInnis MG, De Paulo JR: Panic disorder with familial bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 42:90–95Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. MacKinnon DF, Xu J, McMahon FJ, Simpson SG, Stein OC, McInnis MG, De Paulo JR: Bipolar disorder and panic disorder in families: an analysis of chromosome 18 data. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:829–831Link, Google Scholar

11. Savino M, Perugi G, Simonini E, Soriani A, Cassano GB, Akiskal HS: Affective comorbidity in panic disorder: is there a bipolar connection? J Affect Disord 1993; 28:155–163Google Scholar

12. Johnson TH, Ward T (eds): The Letters of Emily Dickinson, vols 1–3. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1958Google Scholar

13. Wolff CG: Emily Dickinson. New York, Alfred A Knopf, 1986Google Scholar

14. Akiskal HS, Akiskal K: Reassessing the prevalence of bipolar disorders: clinical significance and artistic creativity. Psychiatrie & Psychobiologie 1988; 3:29–36Google Scholar

15. Jamison KR: Mood disorders and patterns of creativity in British writers and artists. Psychiatry 1989; 52:125–134Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Jamison KR: Touched With Fire. New York, Free Press, 1993Google Scholar

17. Schildkraut JJ, Hirshfeld AJ, Murphy JM: Mind and mood in modern art, II: depressive disorders, spirituality, and early deaths in the abstract expressionist artists of the New York School. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:482–488Link, Google Scholar

18. Johnson TH (ed): The Poems of Emily Dickinson, vols 1–3, 1951. Cambridge, Mass, Belknap Press (Harvard University Press), 1979Google Scholar

19. Eberwein JD (ed): An Emily Dickinson Encyclopedia. Westport, Conn, Greenwood Press, 1998Google Scholar

20. Lombroso C: L’homme all genie: Bibliotica Scientifica Internazionale, vol 16. Milan, Dumolard, 1872Google Scholar

21. Miller R: The Poetry of Emily Dickinson. Middletown, Conn, Wesleyan University Press, 1968Google Scholar

22. Webster N: An American Dictionary of the English Language. New York, Converse, 1844Google Scholar

23. Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Klein DN, Gotlib IH: Natural course of adolescent major depressive disorder in a community sample: predictors of recurrence in young adults. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1584–1591Google Scholar

24. Sewall R: The Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1974Google Scholar

25. Beard GM: Neurasthenia or nervous exhaustion. Boston Med Surgical J 1869; 3:217–220Crossref, Google Scholar

26. Andreasen NC: Creativity and mental illness: prevalence rates in writers and their first-degree relatives. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:1288–1292Google Scholar

27. Dickinson SF: Alumni File Letters to Mr Eastman. Hanover, NH, Dartmouth College, Rauner Library, Rauner Special CollectionsGoogle Scholar