Psychiatric Treatment in Primary Care Patients With Anxiety Disorders: A Comparison of Care Received From Primary Care Providers and Psychiatrists

Abstract

Objective: This study examined psychiatric treatment received by primary care patients with anxiety disorders and compared treatment received from primary care physicians and from psychiatrists. Method: Primary care patients at 15 sites were screened for anxiety symptoms. Those screening positive were interviewed to assess for anxiety disorders. Information on psychiatric treatment received and provider of pharmacological treatment were collected. Results: Of 539 primary care participants with at least one anxiety disorder, almost half (47.3%) were untreated. Nearly 21% were receiving medication only for psychiatric problems, 7.2% were receiving psychotherapy alone, and 24.5% were receiving both medication and psychotherapy. Patients receiving psychopharmacological treatment received similar medications, often at similar dosages, regardless of whether their prescriber was a primary care physician or a psychiatrist. One exception was that patients were less likely to be taking benzodiazepines if their provider was a primary care physician. Those receiving medications from a primary care provider were also less likely to be receiving psychotherapy. Overall, patients with more functional impairment, more severe symptoms, and comorbid major depression were more likely to receive mental health treatment. Members of racial/ethnic minority groups were less likely to be treated. Frequently endorsed reasons for not receiving pharmacological treatment were that the primary care physician did not recommend it and the patient did not believe in taking medication for emotional problems. Conclusions: Nearly half the primary care patients with anxiety disorders were not treated. However, when they were treated, the care received from primary care physicians and psychiatrists was relatively similar.

More than half of patients with a psychiatric problem receive treatment for their symptoms from a primary care physician rather than a mental health specialist (1 , 2) . General medical physicians also facilitate or impede access to mental health specialty services through referral decisions (3 , 4) . A survey of U.S. adults with depressive and anxiety disorders found that only 1.9% visited a mental health specialist without seeing a primary care physician (5) .

Anxiety disorders are among the most common mental health problems seen in a primary care setting. As much as one-third of primary care patients have been found to have significant anxiety symptoms (6) . Approximately 15% have a current anxiety disorder, and 24% have a lifetime anxiety disorder, as assessed by diagnostic interview (7) . Primary care patients with anxiety disorders typically have considerable disability and impairment in functioning (8 , 9) . They also have high utilization of general medical services, resulting in higher health care costs (10) .

Only a few studies have investigated the nature of mental health treatments for primary care patients with anxiety disorders. An analysis of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey database from 1985 to 1998 found that when anxiety was diagnosed, treatment was offered in over 95% of visits to psychiatrists but in only 60% of visits to a primary care physician (11) . An international study coordinated by the World Health Organization documented the prescribing patterns of primary care physicians in regard to the treatment of psychiatric disorders (12) . Of primary care patients with anxiety disorders, 7.7% were found to be treated with antidepressant medications, 34.1% with anxiolytics and hypnotics, and 21.1% with miscellaneous other medications. The use of antidepressants (in 23% of the patients with anxiety disorders) was noticeably higher in the United States than in other countries. In the study most similar to our own, primary care patients with anxiety disorders self-reported the treatment they received. Just over half (58.7%) received any psychotropic medication, 35.8% received counseling by their primary care provider, and only 31.3% of patients reported treatment that met the authors’ criterion for quality care (13) . However, this study did not investigate differences in care received from primary care providers and psychiatrists. In the treatment of depression, when primary care physicians prescribe antidepressants, they use dosages lower than recommended by guidelines and lower than used by psychiatrists (14 , 15) .

The current study was designed to address the relative lack of information on the type of treatments prescribed to patients with anxiety disorders seen at primary care settings. The specific goals were to provide descriptive information on the proportion of primary care patients with anxiety disorders who receive mental health treatment and to examine potential differences in treatment received from primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Predictors of receiving treatment for an anxiety disorder were explored to ascertain whether mental health treatments are more likely to be initiated for certain subgroups of patients.

Method

Study Design

The subjects were participants in the Primary Care Anxiety Project, which is a longitudinal study of individuals with anxiety disorders in primary care settings (16) . Patients with anxiety disorders are assessed at study baseline, 6 and 12 months postbaseline, and then yearly thereafter in follow-up interviews. This report examines baseline data only.

The Primary Care Anxiety Project was conducted across 15 primary care practices in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Vermont. Both internal medicine and family practice offices were involved, including four independent practice offices, four university-affiliated clinics, and seven clinics at university teaching hospitals.

Participant Recruitment and Assessment

Participants in the Primary Care Anxiety Project were recruited from primary care waiting rooms. Inclusion criteria were the following: a general medical appointment on the day of screening, at least 18 years of age, English proficiency, and meeting DSM-IV criteria for one or more of seven intake anxiety disorder diagnoses. Exclusion criteria included active psychosis, the absence of a current address and telephone number, and pregnancy.

A research assistant asked all eligible participants in the primary care waiting room if they were interested in participating in a study of different types of stress or nervousness. Interested patients were asked to complete a screening form designed to evaluate the key features of DSM-IV anxiety disorders. The patients who screened positive for anxiety symptoms were offered a full diagnostic interview. After complete description of the study had been given, written consent was obtained from all participants. Institutional review boards at each of the sites approved the research protocol. A detailed description of recruitment has been published (17) .

Measures

Anxiety Screener

A 32-item self-report measure was used to assess the key features of each anxiety disorder. Items were derived from the central features of DSM-IV criteria. To avoid exclusion of potentially eligible participants, the screener was designed to be highly sensitive. A separate validation study conducted on this instrument (16) found that the screening form had a sensitivity of 1.0 and a specificity of 0.67. No individual in the validation sample screened negative but was found to have a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) anxiety disorder diagnosis.

Clinical Interview

All subjects were diagnosed with the SCID (18) . After the psychotic screen, the SCID anxiety disorders module was administered first. The participants who received an anxiety disorder diagnosis proceeded to complete the mood, substance use, and eating disorders modules.

Psychosocial Functioning

At the completion of the SCID, the interviewer rated the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) Scale score that is part of the DSM-IV system (19) . This is a measure of functioning and symptom severity. The interviewers also rated the patient on the Global Social Adjustment Scale as part of the interview based on the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation for DSM-IV (20) . This is a 1–5 scale (1=no impairment and very good functioning, 5=marked or severe impairment) indicating overall level of current psychosocial functioning.

Nonpsychiatric medical problems were assessed with a medical history form designed for the study (16) . The medical history form is an interviewer-administered questionnaire in which participants are asked whether or not they have ever had any of 18 different illnesses or medical problems. For the present study, a dichotomous (yes/no) variable was constructed indicating the presence of a major medical illness. This was coded “yes” for any participant reporting current asthma, cancer, diabetes, epilepsy, heart disease, kidney disease, liver disease, lung or respiratory illness, stroke, and/or thyroid disease.

Treatment Received

Information regarding the participant’s use of psychotropic medications was captured on the psychotropic treatment section of the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation for DSM-IV (20) . Psychosocial treatment received was measured on the types-of-treatment form, an interviewer-administered form designed for the present study, and on the Psychosocial Treatments Interview for Anxiety Disorders (21) .

A subgroup of participants not receiving treatment was interviewed with the treatment-not-received form, designed for the present study. This is an interviewer-administered measure examining reasons for not receiving and/or complying with recommended mental health treatment.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics (means and percents) were used to characterize the type of treatment received for the group as a whole. Comparisons between the type and dosage of medications prescribed by primary care physicians and psychiatrists were made with chi-square statistics and t tests, respectively.

Potential predictors of receiving any mental health treatment and of receiving pharmacotherapy from a psychiatrist versus a primary care physician were examined. The initial pool of potential predictors included age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, insurance type, income, marital status, symptom severity, and functioning, as measured by the GAF and Global Social Adjustment scales, the presence of major depressive disorder, the presence of alcohol/substance use disorder, the presence of a major nonpsychiatric medical illness, the number of anxiety disorders, and the age of onset of anxiety disorders. We reduced this potential pool by examining the univariate relationship between each predictor and each outcome variable. All individual variables related to the outcome variable at p≤0.05 were entered into a stepwise logistic regression. The final logistic regression models were examined, including all remaining variables, which were entered at a 0.05 level of significance.

Results

Group Characteristics

A detailed description of recruitment and group selection, including rates of refusal, has been published (17) . Five hundred thirty-nine primary care patients met criteria for one or more of the following index anxiety disorders and were enrolled in the Primary Care Anxiety Project: posttraumatic stress disorder (N=199, 37%), social phobia (N=182, 34%), panic disorder with agoraphobia (N=150, 28%), generalized anxiety disorder (N=135, 25%), panic disorder without agoraphobia (N=85, 16%), agoraphobia without history of panic disorder (N=23, 4%), mixed anxiety-depressive disorder (N=10, 2%), or generalized anxiety disorder features occurring exclusively within the course of a mood disorder (N=29, 5%). A total of 50.5% of the patients had more than one of these anxiety disorders. Comorbid nonanxiety disorders included major depressive disorder (41%), alcohol/substance use disorders (10%), and eating disorders (11%).

The average age of the participants was 39 years. The majority were women (76%) and Caucasian (83%). Of the 91 participants who were members of a minority group, 41 were African American, 20 were Hispanic, nine were Native American, seven were Asian, and 14 were other. Half of all participants were married; the majority had at least a high school education (67%), and 40% were employed full-time.

Overall Treatment of Anxiety Disorders in Primary Care

Of the total 539 primary care patients with an anxiety disorder, 52.7% (N=284) were receiving treatment for psychiatric problems. One hundred thirty-two patients (24.5%) were receiving both psychopharmacological treatment and psychotherapy, 113 (21.0%) were receiving medication only, and just 39 (7.2%) were receiving psychotherapy only.

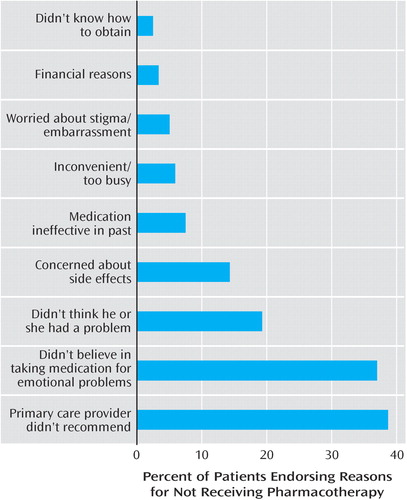

The reasons given by the participants for not receiving pharmacotherapy are shown in Figure 1 and for not receiving psychotherapy in Figure 2 . Among the top two most frequently endorsed reasons for not receiving both types of treatment was that the patient did not believe in treatment for emotional problems. The most commonly endorsed reason for not receiving pharmacotherapy was that the primary care provider did not recommend this treatment (38.7%). This was also endorsed by 17% of those not receiving psychotherapy. Additionally, not realizing that he or she had a treatable emotional problem was the third most common reason for not receiving pharmacotherapy (endorsed by 19.3%) and the second most common reason for not receiving psychotherapy (23.5%). Barriers related to treatment access, such as cost, convenience, and knowing how to obtain care, were commonly endorsed as reasons for not receiving psychotherapy but rarely given as barriers to pharmacotherapy.

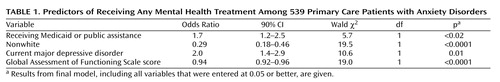

To understand the clinical and demographic characteristics associated with a greater likelihood of receiving treatment for psychiatric problems, stepwise logistic regression was conducted. After prescreening variables (as described), the following variables were eligible for examination of receiving/not receiving any treatment: income, ethnicity/race, receiving Medicare or public assistance, GAF Scale score, number of current anxiety disorders, and currently experiencing episode of major depressive disorder. The results of a forward selection stepwise logistic regression analysis revealed that four variables entered the predictive model at p≤0.05 ( Table 1 ). Primary care patients with anxiety disorders who received mental health treatment were significantly more likely to have poorer functioning and more severe symptoms, as measured by the GAF Scale, to have a concurrent diagnosis of major depressive disorder, to be receiving Medicare or public assistance, and not to be a member of a minority group.

We ran post hoc analyses to better understand the finding that patients with Medicare were more likely to receive treatment. We found that participants with Medicare were more likely to be receiving treatment (67%) than either participants with no insurance (42% in treatment) (χ 2 =9.73, df=1, p<0.01) or those with private insurance (49% in treatment) (χ 2 =12.58, df=1, p<0.001). There was no difference in treatment rates between the participants with no insurance and those with private insurance (χ 2 =0.93, df=1, p=0.33).

Comparisons of Treatment Received From Psychiatrists and Primary Care Physicians

Psychopharmacological Treatment Received

Of the 244 participants who were receiving medication treatment, 100 (41.0%) obtained their medication from their primary care physician, 98 (40.2%) from their psychiatrist, and 7 (2.9%) from other sources (e.g., from their gynecologist or from a family member’s prescription). These data were missing or the source was unknown for 39 individuals (16.0%). Among those who received their medication from primary care providers or psychiatrists, 60.4% (119 of 197) of the participants received selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, 34.5% (68 of 197) received benzodiazepines, 11.7% (23 of 197) received tricyclic antidepressants, 14.7% (29 of 197) received trazodone, and 3% (6 of 197) received buspirone.

The patients of primary care physicians, compared to patients of psychiatrists, were significantly less likely to receive benzodiazepines (24.0% [24 of 100] versus 45.4% [44 of 97], respectively; χ 2 =9.9, df=1, p<0.002). There were no significant differences in the rates of receiving SSRIs/selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (66.0%% [66 of 100] versus 54.6% [53 of 97], respectively), tricyclic antidepressants, (10.0% [10 of 100] versus 13.4% [13 of 97]), or trazodone (15.0% [15 of 100] versus 14.4% [14 of 97]). Few patients reported taking buspirone, prescribed by either primary care physicians (one patient) or psychiatrists (five patients).

An examination of mean doses of SSRIs/selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors reported by primary care patients revealed there were no significant differences between the two types of providers. However, when the prescriber was a psychiatrist compared to a primary care physician, there was a tendency for patients to report taking somewhat higher doses of sertraline (mean=110 mg/day, SD=74, N=15, versus mean=70 mg/day, SD=40, N=25, respectively; t=1.9, df=19.1 [separate variance test], p<0.07) and fluoxetine (mean=35 mg/day, SD=26, N=17, versus mean=22 mg/day, SD=9, N=18; t=1.99, df=19.9 [separate variance test], p=0.06). Dosages of paroxetine were similar (mean=19 mg/day, SD=14, N=14, for psychiatrists and mean=23 mg/day, SD=20, N=23, for primary care physicians). Only one patient received venlafaxine from his or her primary care provider (75 mg/day compared to mean=191 mg/day, SD=142, for eight patients treated by psychiatrists). No patient received citalopram from a primary care physician (enrollment overlapped its introduction in the United States).

When we used the same initial pool of variables (described above), the following were eligible for the regression analysis: marital status, race/ethnicity, Global Social Adjustment Scale score, GAF Scale score, and Medicare/public assistance. Stepwise logistic regression (N=194) predicting whether a patient received medication treatment from his or her primary care physician or a psychiatrist revealed only one significant predictor: patient’s Global Social Adjustment Scale score (Wald χ 2 =12.3, df=1, p<0.001; odds ratio=1.8). Primary care patients with anxiety disorders who received medication from a psychiatrist had poorer psychosocial functioning, as measured by the Global Social Adjustment Scale.

Psychotherapy Received

Of the 198 patients receiving psychotropic medications from either a psychiatrist or a primary care physician, the individuals whose pharmacotherapy was prescribed by a psychiatrist were significantly more likely to receive conjunctive psychotherapy (χ 2 =36.01, df=1, p<0.0001). Thirty-three (33%) of the patients receiving medications from a primary care provider and 74 (76%) of the patients whose medications were prescribed by a psychiatrist reported also receiving psychotherapy.

Discussion

Several findings emerged from the current study that are relevant to the quality of care provided to patients with anxiety disorders who are seen in primary care settings.

Only about half of the primary care patients with anxiety disorders were currently receiving any mental health treatment.

The patients taking psychotropic medications were equally likely to be receiving the prescription from their primary care provider as from a psychiatrist.

SSRIs/selective norephinephrine reuptake inhibitors were the most commonly prescribed psychotropic medication, by both primary care providers and psychiatrists.

Patients were less likely to be taking benzodiazepines prescribed by primary care physicians than by psychiatrists.

Individuals receiving psychotropic medications from a primary care physician were less likely than those getting pharmacotherapy from a psychiatrist to also be receiving psychotherapy.

Members of racial/ethnic minority groups were less likely to be receiving mental health treatment.

Individuals with more impairment and more severe symptoms, as evidenced by lower GAF Scale scores, or with a concurrent major depressive disorder were more likely to receive mental health treatment.

Primary care patients who were not receiving pharmacotherapy for their anxiety disorders stated that two of the main reasons for not being treated were that their doctor never recommended treatment (38.7%) and that they did not believe in medication for emotional problems (37%). The most frequently endorsed reasons for not receiving psychotherapy were that they did not believe in psychotherapy (27.5%) and that the patients did not know they had a problem (23.8%).

The fact that only about half of primary care patients with an anxiety disorder were receiving mental health treatment is consistent with the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey that reported treatment was offered at 60% of the primary care office visits for patients with anxiety (11) . These data suggest that there remains substantial room for further improvement in reducing the burden of anxiety disorders on society.

Although only about half of the patients with anxiety disorders received any treatment, when pharmacological treatment was implemented, the rates of receiving antidepressants (SSRIs/selective norephephrine reuptake inhibitors) from primary care physicians were as high as those from psychiatrists, suggesting that many primary care physicians are aware of new developments in pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders. Similar to our data, a multinational study of prescribing patterns in primary care found that in the United States, 23% of the patients with an anxiety problem received a prescription for an antidepressant (12) . Patients were less likely to receive benzodiazepines from primary care physicians compared to psychiatrists perhaps because of concern by primary care physicians for a variety of adverse events and abuse liability that may be associated with these agents (22 , 23) . We also found that the only significant predictor of receiving medication from a psychiatrist versus a primary care physician was severity of functional impairment. Therefore, it may be that psychiatrists prescribe more benzodiazepines than do primary care physicians because psychiatrists are treating a more severely impaired population. In terms of dosing, there was no significant difference between the dosages reported by patients prescribed their medication by primary care physicians and psychiatrists. However, the difference in dosages for sertraline and fluoxetine fell just short of statistical significance. The group sizes were too small to detect anything but large differences, so this issue needs further investigation.

Our study did not directly evaluate the physician’s viewpoint on why treatment was not implemented for many patients with anxiety disorders. Analyses of demographic and clinical predictors suggest the possibility that primary care physicians have a high threshold for recognition and/or treatment of anxiety disorders. This may also be the reason why patients receiving public assistance were more likely to be receiving treatment than their counterparts with private insurance. Patients with public insurance may have had worse functioning and appeared more severely ill. When patients had more severe symptoms, worse functioning, or comorbid depression, primary care physicians were perhaps more likely to recognize that a psychiatric disorder was present and to consequently implement treatment or refer patients to a psychiatrist for treatment. Whether the primary care physicians are not aware of the anxiety disorder when functioning is higher or whether they are hesitant to treat higher-functioning patients with anxiety disorders is not clear. Our data indicate that many patients reported that they were unaware of having a problem or that their primary care doctor did not recommend treatment, suggesting at least a lack of communication between the primary care physician and the patient. Further research is needed to understand how often primary care physicians recognize anxiety disorders but decide not to communicate their diagnoses with patients and not to treat such disorders and whether primary care physicians are continuing to not recognize such disorders when impairment is less severe, as has been documented in the past (6 , 24) .

Of particular concern is the finding that members of minority groups were less likely to receive mental health treatment. This is consistent with the results of a recent primary care study that found that ethnic minorities were less likely to receive appropriate antianxiety medications (13) . Another previous study failed to find any differences in the prescribing of antidepressants to non-Latino white patients and Latino patients in primary care (25) . Further studies are needed to determine if the ethnic disparity found in our study is unique to anxiety disorders or unique to the sites or geographic areas of the current study. Additionally, it is important to note that our study measured treatment received, as reported by the patient, rather than treatment prescribed, as reported by the physician. Therefore, an important agenda for future research is to sort out whether barriers to minorities receiving treatment for anxiety disorders are related more to physician behavior or cultural attitudes toward medication or therapy among patients.

For some primary care physicians, failure to adequately treat anxiety disorders may be related to a belief that the anxiety is secondary to a nonpsychiatric medical disorder. However, in the present study, we found that the presence of a major nonpsychiatric medical illness was not related to the likelihood of receiving treatment.

Our data also suggest that some of the barriers to effective treatment lie within the patient, rather than the primary care doctor. One of the most common reasons for not receiving pharmacotherapy was not believing in the use of medication for emotional problems, and the most common reason for not receiving psychotherapy was not believing in the use of psychotherapy. These findings indicate that efforts to improve the treatment of anxiety disorders in primary care must involve patient education, not solely interventions directed at providers. In the treatment of major depressive disorder, an intervention that focused on counseling primary care patients about medication treatment was found to improve adherence and enhance outcomes among those receiving higher dosages, relative to treatment as usual (26) . The value of patient education about anxiety disorders and their treatment also needs to be investigated.

Limitations of the current study include the fact that all of the primary care sites were in one geographic area of the United States. Research involving a broader range of sites across the country, including sites with larger populations of minorities served, would be important to examine the generalizability of our findings. Furthermore, our investigation is not an epidemiological study in that we did not systematically interview all members of the available population and in that by asking patients if they were interested in participating in a study about “stress or nervousness” we may have biased the study group toward those with anxiety disorders. Thus, these data are not meant as a report of anxiety disorder prevalence rates in primary care. Additionally, this study did not examine the frequency of visits to psychiatrists and primary care physicians to monitor anxiety and treatment. A potential unreported difference in care between these provider types may be the follow-up received, especially after the receipt of a prescription for a new medication. The current data are also limited in that they provide only a single “snapshot” about the treatment of anxiety disorders after such patients have been seen in a primary care setting. Some primary care physicians might take a “watchful waiting” approach with anxiety disorders to see if the symptoms resolve over time without treatment. If anxiety symptoms persist over time, primary care physicians might be compelled to implement treatment or refer the patient for specialty care. Longitudinal follow-up data would provide such information on whether the rate of treatment increases if symptoms are persistent. The Primary Care Anxiety Project is currently tracking the patient cohort described herein, with assessments at 6 and 12 months postintake and then yearly thereafter. Thus, we will eventually be able to address the issue of how treatments, or lack of treatment, change over time for patients with anxiety disorders.

1. Price D, Beck A, Nimmer C, Bensen S: The treatment of anxiety disorders in a primary care setting. Psychiatr Q 2000; 7:31–45Google Scholar

2. Shear MK, Schulberg HC: Anxiety disorders in primary care. Bull Menninger Clin 1995; 59(suppl A):A73–A85Google Scholar

3. Beardsley RS, Gardocki GJ, Larson DB, Hidalgo J: Prescribing of psychotropic medication by primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:1117–1119Google Scholar

4. Weiller E, Bisserbe JC, Maier W, Lecrubier Y: Prevalence and recognition of anxiety syndromes in five European primary care settings. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 173(suppl 34):18–23Google Scholar

5. Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB: The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:55–61Google Scholar

6. Fifer SK, Mathias SD, Patrick DL, Mazonson PD, Lubeck DP, Buesching DP: Untreated anxiety among adult primary care patients in a health maintenance organization. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:740–750Google Scholar

7. Nisenson LG, Pepper CM, Schwenk TL, Coyne JC: The nature and prevalence of anxiety disorders in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1998; 20:21–28Google Scholar

8. Roy-Byrne PP, Stein MB, Russo J, Mercier E, Thomas R, McQuaid J, Katon WJ, Craske MG, Bystritsky A, Sherbourne CD: Panic disorder in the primary care setting: comorbidity, disability, service utilization, and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:492–499Google Scholar

9. Sherbourne CD, Wells KB, Meredith LS, Jackson CA, Camp P: Comorbid anxiety disorder and the functioning and well-being of chronically ill patients of general medical providers. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:889–895Google Scholar

10. Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, Barlow W: Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:353–357Google Scholar

11. Harman JS, Rollman BL, Hanusa BH, Lenze EJ, Shear MK: Physician office visits of adults for anxiety disorders in the United States, 1985–1998. J Gen Intern Med 2002; 17:165–172Google Scholar

12. Linden M, Lecrubier Y, Bellantuono C, Benkert O, Kisely S, Simon G: The prescribing of psychotropic drugs by primary care physicians: an international collaborative study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1999; 19:132–140Google Scholar

13. Stein MB, Sherbourne CD, Craske MG, Means-Christensen A, Bystritsky A, Katon W, Sullivan G, Roy-Byrne PP: Quality of care for primary care patients with anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:2230–2237Google Scholar

14. McManus P, Mant A, Mitchell P, Britt H, Dudley J: Use of antidepressants by general practitioners and psychiatrists in Australia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2003; 37:184–189Google Scholar

15. Donoghue JM, Tylee A: The treatment of depression: prescribing patterns of antidepressants in primary care in the UK. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168:164–168Google Scholar

16. Weisberg RB, Bruce SE, Machan JT, Kessler RC, Culpepper L, Keller MB: Nonpsychiatric illness among primary care patients with trauma histories and post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Serv 2002; 53:848–854Google Scholar

17. Weisberg RB, Maki KM, Culpepper L, Keller MB: Is anyone really M.A.D.? the occurrence and course of mixed anxiety-depressive disorder in a sample of primary care patients. J Nerv Ment Dis 2005; 193:223–230Google Scholar

18. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department, 1996Google Scholar

19. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994Google Scholar

20. Keller MB, Warshaw MG, Dyck I, Dolan RT, Shea MY, Riley K, Shapiro R: LIFE-IV: The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation for DSM-IV. Providence, RI, Brown University, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, 1997Google Scholar

21. Steketee G, Perry JC, Goisman RM, Warshaw MG, Massion AO, Peterson LG, Langford L, Weinshenker N, Farreras IG, Keller MB: The Psychosocial Treatments Interview for Anxiety Disorders: a method for assessing psychotherapeutic procedures in anxiety disorders. J Psychother Pract Res 1997; 6:194–210Google Scholar

22. Rickels K, Schweizer E, Lucki I: Benzodiazepine side effects, in American Psychiatric Association Annual Review, Vol 6. Edited by Hales RE, Frances AJ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1987, pp 781–801Google Scholar

23. Woods JH, Katz JL, Winger G: Benzodiazepines: use, abuse, and consequences. Pharmacol Rev 1992; 44:151–347Google Scholar

24. Borus JF, Howes MJ, Devins NP, Rosenberg R, Livingston WW: Primary health care providers’ recognition and diagnosis of mental disorders in their patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1988; 10:317–321Google Scholar

25. Sleath BL, Rubin RH, Huston SA: Antidepressant prescribing to Hispanic and non-Hispanic white patients in primary care. Ann Pharmacother 2001; 35:419–423Google Scholar

26. Peveler R, George C, Kinmonth AL, Campbell M: Thompson C: Effect of antidepressant drug counselling and information leaflets on adherence to drug treatment in primary care: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 1999; 319:612–615Google Scholar