Identification and Treatment of a Pineal Region Tumor in an Adolescent With Prodromal Psychotic Symptoms

Abstract

An adolescent male patient originally presented to a prodromal clinical research program with severe obsessive-compulsive behaviors and subthreshold symptoms of psychosis, which eventually developed into first-rank psychotic symptoms. The patient was followed over a 2-year period. His symptoms did not respond to psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy. However, when a pineal region tumor was discovered and treated with chemotherapy and autologous stem cell rescue, both psychotic symptoms and psychosocial functioning reverted toward baseline. Although subcortical brain structures have been implicated in the pathophysiology of idiopathic psychosis, reports of psychiatric sequelae of treatment of subcortical tumors are rare. Etiological pathways that may have played a role in symptom development are of particular interest, as understanding these mechanisms may shed light on the pathophysiology of psychotic disorders more generally.

Case Presentation

“David,” a Hispanic male, was referred at age 17 by his psychologist to the clinical research program of the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) Center for Assessment and Prevention of Prodromal States (CAPPS) because of subthreshold psychotic symptoms and behaviors believed to represent a potential precursor to an axis I psychotic disorder (1). At the intake interview, David's mother reported that his early developmental history was unremarkable, with no mental health-related difficulties during childhood aside from some mild attentional problems. Notably, David had been an A student in elementary school and was accepted into a gifted program.

David began to show a marked behavioral decline at the onset of puberty. When he was in the eighth grade (age 13), his parents were undergoing a divorce, and both his teachers and parents reportedly viewed his presentation of mild depressive symptoms and attentional problems as an adjustment disorder related to this situation. However, David continued to show signs of disturbance, and in the ninth grade his grades had dropped to the D range. David's mother had also noticed a decline in verbal expression, and around this time he began to exhibit unusual behaviors—for example, making idiosyncratic hand gestures, exhibiting a preoccupation with checking the time, insisting that the bed covers had to be folded a certain way before he could fall asleep, and consuming excessive amounts of salty foods, such as ketchup and peanuts. As the year progressed, David shifted from being preoccupied with salty foods to excessively drinking water, which was diagnosed as psychogenic polydipsia. He was referred for psychiatric treatment at that time, although psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy (fluvoxamine at 300 mg/day) did not ameliorate the symptoms. David remained in psychotherapy for the next several years, and fluvoxamine was eventually discontinued.

Throughout the 10th grade, David's verbal expression continued to decline. His mother reported that David was expressing himself only in brief phrases consisting of a few words at a time. David was transferred to a charter school in the 11th grade. That winter, David began to exhibit unusual thought content (detailed below), and his treatment providers referred him to the CAPPS program for further evaluation and follow-up. He was evaluated with the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (2, 3), a semistructured diagnostic interview consisting of five components: the 19-item Scale of Prodromal Symptoms (1), a version of the Global Assessment of Functioning with well-defined anchor points, the DSM-IV schizotypal personality disorder checklist, a questionnaire on family history of mental illness, and a checklist for the Criteria of Prodromal Syndromes. The evaluation revealed that David had a euthymic mood state but was exhibiting attenuated positive symptoms of psychosis. He endorsed a belief in mind reading (reporting about 50% conviction) and indicated that he felt like he was at the center of people's attention at times. This concern sometimes prevented him from leaving the house. David also reported that in the past month he had repeatedly heard clapping and hissing sounds but was unable to find their source. Based on these symptoms, David met research criteria for attenuated positive prodromal syndrome (1–3) and was invited to participate in the CAPPS program. The 2-year longitudinal course of each of David's positive prodromal symptoms is summarized in Table 1.

| Symptom | Baseline | 6 Months (Psychosis Onset) | 12 Months (Ongoing Tumor Treatment) | 24 Months (Posttreatment Recovery) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unusual thought content | 4 | 6 | 3 | 1 |

| Suspiciousness | 5 | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Grandiosity | 1 | 3 | 5 | 0 |

| Perceptual abnormalities | 3 | 6 | 4 | 0 |

| Disorganized communication | 4 | 6 | 1 | 1 |

TABLE 1. Longitudinal Progression of Positive Symptoms in an Adolescent With a Pineal Region Tumor, as Rated on the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromesaa

At this point, David was receiving D's and F's in school. Results of a neuropsychological test battery indicated a full-scale IQ estimate of 88 (21st percentile), based on the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (4). Although David had not received any prior cognitive evaluations, it is likely that this score represented a marked drop from his premorbid level of cognitive function, given his previous level of achievement. An MRI scan without contrast, performed as part of a neurological consultation, did not reveal any irregularities, although the scan was terminated early when David was no longer able to lie still.

Over the course of follow-up assessments, examiners learned that David was exhibiting additional behaviors that were not characteristic prodromal symptoms and may have been suggestive of neurological dysfunction. He continued to exhibit stereotyped and idiosyncratic hand gestures resembling gang signs and adopted a bizarre and elaborate series of handshakes. He had begun to wander away from home, becoming lost and talking in a familiar manner to strangers. He also lost orientation to time and date. He began to engage in self-injurious behavior, such as scraping his arm against the wall, which his mother noted may have been an attempt “to get attention” at school. During a subsequent interview, David's mother reported that her son had recently begun to occasionally drag his right foot. As the year progressed, David expressed an interest in learning to write with his left (nondominant) hand, although he explained this by saying it was a strategy to avoid schoolwork.

During the period following David's enrollment in the CAPPS program, he did not appear to benefit from weekly psychotherapy or several consecutive regimens of atypical antipsychotics, including quetiapine and aripiprazole. The polydipsia had begun to severely impair David's functioning, and on one occasion he was hospitalized because of a disruption of his equilibrium resulting from electrolyte imbalance. After David had been participating in our program for 6 months, he began to express overtly psychotic symptoms, including a belief in mind reading (now with 100% conviction), thought withdrawal, and both olfactory and auditory hallucinations (e.g., he reported a man's and a woman's voices alternating with the message, “You should have stayed in bed”). Given David's severe impairment, disorganization, and need for constant supervision, he was enrolled in short-term residential treatment. His treatment providers believed that he was showing signs of an emerging psychotic disorder.

David had not responded well to treatment in the short-term program, and after 3 months the family made plans to transfer him to a long-term treatment facility. As part of a routine entry examination to this program, another MRI scan was performed, with and without contrast, and this time the results revealed a soft-tissue mass in the region of the dorsal midbrain/pineal cistern. A subsequent biopsy indicated a tumor (29 mm in maximum dimension). The scan also revealed evidence of a small left-sided basal ganglia stroke, which was estimated to have occurred at the time of the onset of lateralized motor difficulties. The tumor also resulted in hydrocephalus with distension of the third and lateral ventricles. Immediately after the diagnostic biopsy, a Rickham reservoir (shunt) was put in place (entering the frontal horn of the right lateral ventricle) to treat edema. David was also taken out of school, antipsychotic medication was permanently suspended, and chemotherapy was begun immediately.

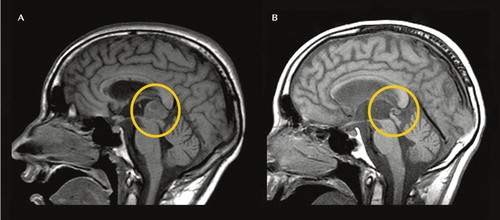

Over the next 6 months, after six cycles of high-dosage chemotherapy, the tumor size had decreased to 7 mm. To help David's body tolerate the high doses of chemotherapy, he began procedures for an autologous stem cell transplant in his last month of chemotherapy, and the procedure was implemented over the next 7 weeks. This combination of treatments was successful, and the tumor size had decreased to 3.7 mm at the conclusion of therapy. Figure 1 illustrates the tumor before and after treatment. However, the tumor's sequelae included panhypopituitarism and diabetes insipidus. During his treatment, David had also begun to complain of peripheral vision loss, which has continued to the present. This persistent symptom may also be secondary to the tumor, as a result of pressure from the swelling and hydrocephalus induced by the tumor that may have caused the pituitary gland to press against the optic chiasm.

FIGURE 1. Baseline and 16-Month Follow-Up MR Images Demonstrating a Pineal Region Mass Before and After Chemotherapy and Stem Cell Transplantaa

aThe image on the left shows the soft-tissue mass in the dorsal midbrain/pineal cistern (circled; 29 mm). The image on the right shows the tumor 16 months later, after treatment (circled; 3.7 mm).

A comprehensive clinical and neuropsychological follow-up assessment was conducted 12 months after David entered the CAPPS program. At this stage in treatment, his tumor had receded from 29 mm to 7 mm, and he was preparing for the stem cell transplant stage of the treatment program. It became clear during the assessment that his behavior had begun to improve toward premorbid functioning. David's psychotic symptoms had remitted to the mild range; he continued to exhibit mild unusual thought content, some paranoia, and perceptual abnormalities, although these symptoms did not reach the psychotic threshold. The polydipsia had abated, likely as a result of treatment for David's diabetes insipidus. In addition, David's cognitive performance had begun to improve as the tumor receded; standardized scholastic testing shortly before the diagnosis of the tumor had indicated that David was performing at a third- to fifth-grade level, and testing during his treatment revealed that his performance had improved to the sixth- to eighth-grade level.

Despite the overall improvements, several ongoing complications were noted. David's motor functioning on the right side of his body remained impaired. He also continued to exhibit mild depressed mood. While many of the unusual behaviors had remitted (e.g., staring at the clock, unusual hand gestures, waving at people), some behaviors persisted; for example, David continued to frequently make the sign of the cross at unusual times during his follow-up interview. His mother indicated that this may have begun as a release of anxiety during the difficult periods of treatment, although it is possible that these gestures were etiologically related to the other unusual motor symptoms.

In the year since his tumor treatment, David has worked closely with a multidisciplinary treatment team (including a psychotherapist, an endocrinologist, and a physical therapist) and his physical health has continued to improve. At the time of this writing (24 months after the baseline assessment at CAPPS), David has returned to public high school for 12th grade and is participating in classes 3 days a week. Although he requires some accommodations (e.g., help with note taking because of the right-sided motor difficulties), the family plans for David to receive the standard curriculum and to graduate from high school. His overall mental health status and social and role functioning have considerably improved. Although he continues to exhibit mild depression and some compulsive motor behaviors (e.g., frequently making the sign of the cross), he has not displayed any recurrence of psychotic symptoms since the treatment for the tumor began. Given this long-standing period of stability, we feel confident in reconceptualizing the case as psychosis due to a general medical condition.

Discussion

Our patient originally presented with a pattern of behavioral decline and unusual thought content suggestive of the prodromal phase of psychotic illness. However, over the course of longitudinal assessment, he developed increasingly severe signs suggestive of an underlying neurological etiology (e.g., foot dragging, lateralized motor symptoms, polydipsia). David's presentation ultimately progressed to fully psychotic symptoms, which remitted after the discovery and treatment of a pineal region tumor. Although causality cannot be conclusively determined, the timeline of symptom development strongly suggests that the tumor and a small left-sided basal ganglia stroke played a primary role in the onset of psychotic and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in this case.

Despite the heavy genetic loading associated with psychotic disorders, organic and environmental origins underlying psychosis have also been well documented. Although the specific pathogenic mechanisms of CNS damage leading to psychosis are unknown, exposure to trauma is associated with an almost fivefold increase in psychotic-like phenomena (5), and psychotic symptoms can also manifest secondary to traumatic brain injury, particularly when a preexisting head injury occurred prior to adolescence (6). These examples also point to the complex gene-environment interactions that are likely to be relevant to the pathophysiology of psychosis (7). Although speculative, it is possible that in David's case an unidentified genetic liability interacted with pathological processes that directly or indirectly resulted from the emerging pineal region tumor. There is also evidence that cerebral neoplasms can be associated with both delusions and hallucinations (8). Notably, a long-term follow-up study of survivors of childhood CNS malignancies found that several of these individuals later developed persistent psychosis many years after the tumor had been successfully treated (9).

The pineal gland is located at the posterior extent of the third ventricle, extending over the tectal plate of the midbrain. Through the production of melatonin and subsequent modulation of sex hormones, the gland is a key structure in sexual development and the onset of puberty. Tumors in this region are rare (accounting for about 1% of all brain tumors), occurring most often in children and young adults (10). The most common of these tumors are germ-cell tumors (germinomas and teratomas), which arise from embryonic remnants of germ cells. These tumors are malignant and invasive and may be life threatening. Although it is not possible to pinpoint when David's tumor first began to develop, it likely coincided with the onset of his behavioral decline during puberty. Previous case reports have indicated that tumors involving the pineal body can result in an irregular course of sexual development in pediatric populations (11). In David's case, however, no signs of either precocious or delayed sexual development were observed; there were no reports of irregular sexual maturation, and during his participation in the CAPPS program, David's Tanner staging scores (12) remained indicative of age-appropriate development. It is possible that David's tumor manifested after the onset of puberty and thus did not observably alter sexual maturation.

However, given the pineal gland's importance in pubertal development and the timing of the tumor and symptoms in David's presentation, this case may provide important clues regarding the pathophysiology of psychotic disorders and their typical onset in adolescence. Several lines of evidence suggest a possible relationship between pineal gland abnormalities and symptoms of thought disorder. Pineal gland irregularities (e.g., calcification) have been observed in patients with schizophrenia (13), and it has been noted that such abnormalities may be related to abnormal nocturnal melatonin secretion in patients with schizophrenia (14). Anecdotal reports have also suggested that high doses of melatonin may exacerbate psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia (15). It is also noteworthy that the pineal area holds a rich concentration of sigma receptors, which bind haloperidol and other antipsychotic agents (16).

There have been very few case reports of psychosis associated with subcortical tumors in children. We were able to identify only three such cases in the literature (17–19), which bore interesting similarities to our patient. Benjamin and colleagues (17) described a 9-year-old boy presenting with a choroid plexus papilloma in the anterior third ventricle and worsening psychotic symptoms, including auditory hallucinations, which remitted after resection of the tumor. Although the origin of psychotic symptoms in that case was unclear, it is possible that the tumor location in the third ventricle—in close proximity to the pineal gland—played a role. In this context it is notable that Sandyk (20) identified third ventricular width and pineal calcifications as the sole neuroradiological indicators that were related to thought disorder severity in chronically psychotic patients.

Mordecai and colleagues (18) described a 13-year-old boy with a suprasellar germinoma involving the basal ganglia bilaterally. Similar to our patient, this case involved left-sided weakness, diabetes insipidus, marked decline in academic function, and both obsessive-compulsive and psychotic symptoms, including a loosely organized delusional system and auditory hallucinations. However, unlike in David's case, this patient's symptoms and cognitive functioning did not substantially improve after treatment of the tumor.

Finally, Craven (19) described a 15-year-old girl who developed intermittent but severe psychotic symptoms, including paranoid delusions and auditory perceptual abnormalities, approximately 14 months after a pineal germinoma was successfully treated. This patient also developed diabetes insipidus and panhypopituitarism secondary to the tumor. Given the atypical course of the patient's psychotic symptoms, the author speculated that the symptom onset may have been related to pituitary hormone replacement therapy, as cases of corticosteroid-induced psychosis have been reported (21).

The MRI that identified the tumor also indicated that David had suffered a small left-sided basal ganglia stroke. Although it bore no obvious relationship to the development of the tumor, it is possible that the enlarging tumor may have resulted in cerebrovascular accident. David's stroke-related basal ganglia dysfunction, along with other potential contributing factors (the tumor and neuroendocrine dysregulation), may have also additively or interactively affected the development of prodromal and ultimately psychotic symptoms. Indeed, cortico-striato-pallido-thalamic circuit malfunction, involving striatal hyperdopaminergia, may predate onset of psychosis in at-risk individuals (22, 23).

It is also possible that the basal ganglia stroke contributed to the onset or exacerbation of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in our patient (e.g., his preoccupation with checking the time, his insistence that the bed covers had to be folded a certain way before he could fall asleep). Disorders that involve the basal ganglia (e.g., Sydenham's chorea, Huntington's disease) can present with both psychotic and obsessive-compulsive symptoms (24–26). Structural and functional neuroimaging studies have demonstrated abnormalities of the basal ganglia and associated cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical circuitry in the pathophysiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder (27). Of particular relevance to David's case, Peterson and colleagues (28) reported three cases in which preexisting obsessive-compulsive symptoms became more severe with the development of cerebral malignancies affecting cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical circuitry and then improved with successful treatment of the tumor. When David began showing excessive consumption of salty foods and then developed polydipsia, these behaviors were originally thought to be manifestations of his obsessive-compulsive behavior, which also included compulsive checking and other routines. However, in hindsight it is clear that what appeared to be compulsive water drinking actually reflected diabetes insipidus, likely related to his subcortical brain pathology.

Conclusion

This report illustrates a compelling case in which the onset of psychotic symptoms coincided with the development of a pineal region tumor and remitted when the tumor receded, which suggests that the tumor was the most likely cause of these symptoms, although other factors, particularly a basal ganglia stroke, may also have contributed. Previous case reports describing subcortical tumors associated with psychosis or worsening obsessive-compulsive symptoms provide further support for the hypothesized causal relationship (17–19).

1. : Symptom assessment in schizophrenic prodromal states. Psychiatr Q 1999; 70:273–287Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. : Prodromal assessment with the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes and the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr Bull 2003; 29:703–715Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. : Prospective diagnosis of the initial prodrome for schizophrenia based on the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes: preliminary evidence of interrater reliability and predictive validity. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:863–865Link, Google Scholar

4. : Manual for the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI). San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1999Google Scholar

5. : Routes to psychotic symptoms: trauma, anxiety, and psychosis-like experiences. Psychiatry Res 2009; 169:107–112Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. : Risk factors in psychosis secondary to traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001; 13:61–69Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. : Gene-environment interactions in schizophrenia: review of epidemiological findings and future directions. Schizophr Bull 2008; 34:1066–1082Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. : Cerebral tumors, in Organic Psychiatry: The Psychological Consequences of Cerebral Disorder, 2nd ed. Edited by Lishman WA. Oxford, UK, Blackwell Scientific, 1987, pp 218–236Google Scholar

9. : Late onset psychosis survivors of central nervous malignancies. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2007; 19:293–297Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. : Cystic lesions of pineal region: MRI and pathology. Neuroradiology 2000; 42:399–402Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. : Precocious puberty due to human chorionic gonadotropin-secreting pineal tumor. Chang Gung Med J 2006; 29:198–202Medline, Google Scholar

12. : Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Arch Dis Child 1970; 45:13–23Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. : Computed tomography study of pineal calcification in schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry 1999; 14:163–166Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. : Melatonin in psychiatric disorders: a review on the melatonin involvement in psychiatry. Front Neuroendocrinol 2001; 22:18–32Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. : Pineal melatonin in schizophrenia: a review and hypothesis. Schizophr Bull 1990; 16:653–662Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. : Des-Tyr1-gamma-endorphin and haloperidol increase pineal gland melatonin levels in rats. Peptides 1983; 4:393–395Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. : Third ventricular choroid plexus papilloma with psychosis. J Neurosurg 1997; 87:103–105Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. : Case study: suprasellar germinoma presenting with psychotic and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:116–119Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. : Pineal germinoma and psychosis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40:6Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. : The relationship of thought disorder to third ventricle width and calcification of the pineal gland in chronic schizophrenia. Int J Neurosci 1993; 68:53–59Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. : Drug-induced mania. Drug Saf 1995; 12:146–153Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. : Elevated striatal dopamine function linked to prodromal signs of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009; 66:13–20Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. : The longitudinal progression of movement abnormalities and psychotic symptoms in adolescents at high risk for psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008; 65:165–170Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. : Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1997; 20:863–883Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. : Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections: clinical description of the first 50 cases. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:264–271; correction, 155:578Abstract, Google Scholar

26. : Schizophrenia, psychosis, and the basal ganglia. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1997; 20:897–910Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. : PANDAS: current status and directions for research. Mol Psychiatry 2004; 9:900–907Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. : Three cases of symptom change in Tourette's syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder associated with pediatric cerebral malignancies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996; 61:497–505Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar