Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated With Streptococcal Infections: Clinical Description of the First 50 Cases

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to describe the clinical characteristics of a novel group of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and tic disorders, designated as pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal (group A β-hemolytic streptococcal [GABHS]) infections (PANDAS). METHOD: The authors conducted a systematic clinical evaluation of 50 children who met all of the following five working diagnostic criteria: presence of OCD and/or a tic disorder, prepubertal symptom onset, episodic course of symptom severity, association with GABHS infections, and association with neurological abnormalities. RESULTS: The children's symptom onset was acute and dramatic, typically triggered by GABHS infections at a very early age (mean=6.3 years, SD=2.7, for tics; mean=7.4 years, SD=2.7, for OCD). The PANDAS clinical course was characterized by a relapsing-remitting symptom pattern with significant psychiatric comorbidity accompanying the exacerbations; emotional lability, separation anxiety, nighttime fears and bedtime rituals, cognitive deficits, oppositional behaviors, and motoric hyperactivity were particularly common. Symptom onset was triggered by GABHS infection for 22 (44%) of the children and by pharyngitis (no throat culture obtained) for 14 others (28%). Among the 50 children, there were 144 separate episodes of symptom exacerbation; 45 (31%) were associated with documented GABHS infection, 60 (42%) with symptoms of pharyngitis or upper respiratory infection (no throat culture obtained), and six (4%) with GABHS exposure. CONCLUSIONS: The working diagnostic criteria appear to accurately characterize a homogeneous patient group in which symptom exacerbations are triggered by GABHS infections. The identification of such a subgroup will allow for testing of models of pathogenesis, as well as the development of novel treatment and prevention strategies. (Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:264–271)

This is the first comprehensive report of a group of patients with childhood-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and tic disorders. The children have different primary diagnoses, including both OCD and tic disorders, but share in common a clinical course characterized by dramatic symptom exacerbations following group A β-hemolytic streptococcal (GABHS) infections. Sir William Osler was actually the first to notice such a relationship when he described “a certain perseverativeness of behavior” in patients with Sydenham's chorea, a variant of rheumatic fever (1). Aside from a few isolated reports (2–4), the importance of his prescient observations went unnoticed until the late 1980s, when we undertook a series of investigations directed at the hypothesis that basal ganglia dysfunction could cause a wide variety of neuropsychiatric symptoms depending upon the nature of both the environmental trigger and the host susceptibility (5). Support for this hypothesis had been provided by pathological reports of basal ganglia involvement in Sydenham's chorea (6) and neuropsychological and neuroimaging evidence of basal ganglia dysfunction in both Sydenham's chorea and OCD (7–11), as well as demonstrations of similar antineuronal antibodies in both disorders (5, 12–14). Further support was generated from longitudinal studies of children and adolescents with OCD and from systematic evaluation of children with Sydenham's chorea. Studies of Sydenham's chorea revealed that obsessive-compulsive symptoms were common during the illness (present in nearly three-quarters of children) and had their onset shortly before the chorea began, suggesting that the obsessive-compulsive symptoms were not “compensatory” for physical disability (because the children were not yet ill when they began to experience obsessions and compulsive rituals) (15, 16). On the basis of these observations, we postulated that children might exhibit only tics or OCD if the “dose” of a presumed etiologic agent was not sufficient to cause frank chorea (5).

Longitudinal follow-up of a group of children and adolescents with OCD revealed that a subgroup of the children had an episodic course characterized by dramatic and acute symptom exacerbations interspersed with periods of relative symptom quiescence (17–19). Of particular note, these exacerbations often followed infections with GABHS. The clinical course of a 10-year-old boy examined early in 1991 is illustrative.

Patient A presented to the child psychiatry clinic with a 2-week history of severe obsessive concerns about contamination from AIDS and other germs, cleaning and hoarding rituals, a nearly constant spitting tic, and choreiform movements (neurologically distinct from chorea). The symptoms had begun abruptly “overnight” and had progressed over a 48-hour period to the point where A was unable to attend school or participate in his usual extracurricular activities. His mother, a medical technologist, brought our attention to the fact that he had been diagnosed with GABHS pharyngitis less than 2 weeks before the onset of these symptoms. She had noted that her older son's tic disorder also had an episodic pattern, with exacerbations typically occurring a few days after he had been ill with a streptococcal pharyngitis; she suggested that “there had to be a connection between the two” events. At the time of initial presentation, A's antistreptococcal antibody titers were markedly elevated (threefold rise), and antineuronal antibody titers (12, 14) were positive. Over the next few weeks, A's OCD symptoms decreased in severity to a subclinical level (occasional contamination obsessions but no spitting, hoarding, or hand washing), and his antibody titers also fell. About 8 months later, after another GABHS infection, A had a dramatic symptom exacerbation, which was again associated with increased antibody titers, and then, slow resolution of his symptoms with a concomitant diminution of titers. Over the ensuing 2 years, each time A's symptoms increased and his medication dose required an upward adjustment, he had positive antistreptolysin O titers; during periods of remission, he was seronegative.

These clinical observations led to the proposal of a unique subgroup of patients with neuropsychiatric disorders that could be identified by the following criteria: 1) presence of OCD and/or a tic disorder, 2) prepubertal symptom onset, 3) episodic course of symptom severity, 4) association with GABHS infection, and 5) association with neurological abnormalities. The five criteria appeared to reliably identify a group of children who shared a common clinical course and were presumed to have a similar pathophysiology. The criteria reflect an underlying hypothesis that autoimmunity mediates the neuropsychiatric symptoms, and so the group was designated by the acronym PANDAS, for pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections.

This report describes the first 50 children meeting the working diagnostic criteria for PANDAS and, in addition, discusses the clinical implications of such a diagnosis and proposes a model of pathogenesis.

METHOD

Establishing the Working Criteria for Diagnosis of PANDAS

Systematic clinical evaluation of children with Sydenham's chorea suggested that specific clinical characteristics might define a homogeneous subgroup of patients with OCD and tic disorders, including Tourette's disorder. Five working criteria were formulated (20) and have been modified slightly, as follows:

1. Presence of OCD and/or a tic disorder: The patient must meet lifetime diagnostic criteria (DSM-III-R or DSM-IV) for OCD or a tic disorder.

2. Pediatric onset: Symptoms of the disorder first become evident between 3 years of age and the beginning of puberty (as is generally true for rheumatic fever [21]).

3. Episodic course of symptom severity: Clinical course is characterized by the abrupt onset of symptoms or by dramatic symptom exacerbations. Often, the onset of a specific symptom exacerbation can be assigned to a particular day or week, at which time the symptoms seemed to “explode” in severity. Symptoms usually decrease significantly between episodes and occasionally resolve completely between exacerbations.

4. Association with GABHS infection: Symptom exacerbations must be temporally related to GABHS infection, i.e., associated with positive throat culture and/or elevated anti-GABHS antibody titers. Of note, the temporal relationship between the GABHS infection and the symptom exacerbation may vary over the course of the illness. In rheumatic fever, there is often a delay of 6–9 months between the last documented GABHS infection and the appearance of symptoms of Sydenham's chorea; however, recrudescences follow the GABHS infections at a much shorter interval, often with a time lag of only several days to a few weeks (22). It appears that the pattern is similar for PANDAS. It should be further noted that because fever and other stressors of illness are known to increase symptom severity, the exacerbations should not occur exclusively during the period of acute illness. Furthermore, as in Sydenham's chorea and rheumatic fever, some symptom recurrences may not be associated with documented GABHS infections (23), so the child's lifetime pattern should be considered when making the diagnosis.

5. Association with neurological abnormalities: During symptom exacerbations, patients will have abnormal results on neurological examination. Motoric hyperactivity and adventitious movements (including choreiform movements or tics) are particularly common. Of note, children with primary OCD may have normal results on neurological examination, particularly during periods of remission. Further, the presence of frank chorea would suggest a diagnosis of Sydenham's chorea, rather than PANDAS. It is particularly important to make this distinction, since Sydenham's chorea is a known variant of rheumatic fever and requires prophylaxis against GABHS; PANDAS does not.

The diagnostic criteria were applied retrospectively to patients seen between 1991 and 1993 and prospectively to those seen thereafter. Each case was presented at a case conference, and consensus opinion was used to determine whether or not the child should be included in the PANDAS category. The assigned diagnoses were then independently confirmed by two of us (H.L.L. and S.E.S.) by strict application of the diagnostic criteria to case summaries; both authors were in complete agreement about the 50 PANDAS and 32 non-PANDAS cases reviewed.

As a further test of the validity of the PANDAS working diagnostic criteria, 20 screening histories (10 PANDAS and 10 non-PANDAS cases) were selected by one of us (L.L.) and identifying information was removed. Five raters (B.K.D., M.G., H.L.L., S.P., and S.E.S.) independently applied the diagnostic criteria to the case summaries, and each rater correctly identified all 20 cases (kappa=1.0).

Subjects

Children with an acute onset or dramatic exacerbations of obsessive-compulsive symptoms and/or tics were sought through mailings to child psychiatrists, pediatricians, and pediatric neurologists, as well as through advertisements in the Tourette's Syndrome Association national newsletter. The advertisements did not include mention of infectious agents as a trigger. The local Tourette's Syndrome Association chapter and the national Obsessive Compulsive Foundation also served as sources of patient referrals. In addition, referrals were sought through presentations at national meetings and direct contact with physicians. As might be expected, referrals were initially limited (one or two patients per month) but increased gradually to the point where we currently conduct four to six telephone screenings per week.

At the time of this report, 270 telephone screenings had been conducted; of these, 109 subjects were invited to come to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) for an in-person screening evaluation. The screening evaluation was conducted by at least two physicians (S.E.S., H.L.L., A.J.A., M.G., and/or S.P.) and consisted of a review of the child's medical records and a clinical interview with the child and his or her parents—this included a complete assessment of the history of the OCD and/or tic disorder and emphasized the chronology of the child's neuropsychiatric symptoms in relationship to environmental triggers.

Children were excluded from study participation if they had a history of Sydenham's chorea, rheumatic fever, or another autoimmune disorder or if examination revealed cardiac abnormalities consistent with prior rheumatic carditis (none of the children was excluded for heart disease.) They were also excluded if they failed to meet the working criteria for the diagnosis of PANDAS; of note, 27 children were excluded at the time of the in-person screening because the interview revealed that they did not have a clear association between streptococcal infections and symptom exacerbations; 32 children were excluded following baseline evaluation. Thus, 50 children met the working diagnostic criteria for PANDAS and are the subjects of this report.

Depending upon their symptom acuity, the children were enrolled in one of two protocols—a placebo-controlled study of penicillin prophylaxis or a randomized-entry controlled study of various immunomodulatory treatments (for acutely ill patients). Both studies had appropriate institutional review board review and approval. All subjects gave written assent, and their parents written consent, to participate in the research investigations.

Procedure

At baseline, subjects completed a battery of neuropsychological tests and a limited number of psychological tests to assess general intelligence level (5, 10). Parents provided historical information about their child (Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents, revised, parent version) (24, 25), themselves (medical history and Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia [26]), and their family members (semistructured family history; instrument available from Dr. Swedo upon request). The subjects underwent systematic medical and psychiatric assessment, including a structured psychiatric interview (Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents, revised, child version) (24, 25) and standardized neurological examination (unpublished examination, available from Dr. Garvey upon request, and the Physical Assessment of Neurologic Subtle Signs examination [27]). Choreiform movements (small, jerky movements occurring irregularly and arrhythmically in different muscles) were assessed by using a modification of the guidelines outlined by Touwen (28). Proximal and distal movements were scored together. A score was assigned according to the amplitude and frequency of the movements over a 30-second period: 0=no movements observed; minimal=occasional small-amplitude movements of fingers; moderate=continuous, small-amplitude movements of fingers, wrists, and proximal areas (arms/shoulders); marked=continuous, moderate-amplitude movements of fingers, wrists, and proximal areas.

The child's neuropsychiatric symptom severity was rated at baseline by using a variety of semistructured scales, including the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (29, 30), Shapiro tic severity rating (31), Global Assessment Scale (32), and NIMH ratings of global, OCD, depression, and anxiety symptom severity (33, 34), as well as three scales designed specifically for use with these children: NIMH irritability, tic severity, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) severity scales (instruments were modified from the NIMH OCD rating scale and are also available from Dr. Swedo upon request).

Baseline laboratory studies included CBC with WBC differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, standard tests of thyroid function, blood chemistries including osmolality and electrolytes, and an immunologic panel that included antinuclear antibody titer and quantitative immunoglobulin levels, among others. (These laboratory studies have not yet been systematically analyzed, and results are not presented in this article.) Each child also had a throat culture for GABHS, antistreptolysin O titers, and antistreptococcal DNAase B titers.

RESULTS

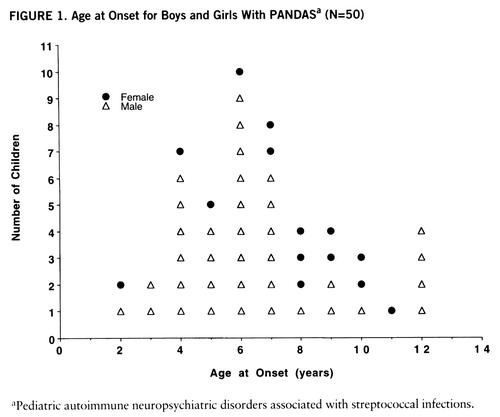

The demographic data for the 50 subjects are shown in table 1. Of particular note is the young age of this group and the early age at onset of both obsessive-compulsive symptoms and tics. The children were evenly divided between those with a primary diagnosis of OCD (N=24, 48%) and those with primary tic disorder (N=26, 52%); 43 (86%) of the children reported obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and 40 (80%) of the children were found to have motor tics. Boys outnumbered girls by a ratio of 2.6:1; below age 8 years, the ratio was 4.7:1. Figure 1 shows this gender distribution plotted against age at onset.

Symptoms of OCD varied by primary diagnosis (table 2). Children with primary OCD reported more washing and checking behaviors than did children with a primary diagnosis of tic disorder (washing: χ2=7.9, df=1, p=0.005; checking: χ2=2.8, df=1, p=0.09).

The severity of the obsessive-compulsive symptoms was moderate, on average, as were motor and vocal tics (table 3).

Psychiatric comorbidity (table 4) was common for the children with PANDAS. ADHD, affective disorders, and anxiety disorders were most prevalent (40%, 42%, and 32%, respectively).

The symptoms of the comorbid diagnoses (particularly ADHD) were also reported to be exacerbated following streptococcal infections, although this was not assessed systematically. In addition, a number of behavioral symptoms were noted to have had their onset concomitant with the onset of the OCD/tics and to have a relapse-remission pattern similar to that of the tics and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. These symptoms are listed in table 5. Most notable among them were emotional lability, separation anxiety, motoric hyperactivity and “fidgetiness,” age-inappropriate behavior, and nighttime difficulties, including severe nightmares and new bedtime fears/rituals (e.g., needing to have a night-light, sleeping outside the parents' bedroom). The symptoms were quite distressing to the children and were clearly distinguishable from the child's premorbid state. These comorbid symptoms always started abruptly, at the same time as the obsessive-compulsive symptoms and tics began or worsened, and were also associated with an increase in antistreptococcal antibody titers.

Association With Neurological Abnormalities

As previously described, 40 children (80%) had a tic disorder. No child had overt chorea, by history or examination. Formal testing for choreiform movements was performed with 26 of the 50 children. Only one child had no choreiform movements noted on baseline examination (although she subsequently demonstrated these movements). Marked choreiform movements were observed in 13 children (50%); five (19%) had moderate choreiform movements, and seven (27%) had minimal choreiform movements. Of note, and contrary to expectations that the movements would decrease with increasing age, a similar number of children above 10 years of age (N=4 of 7, 57%) and under the age of 10 (N=9 of 19, 47%) had marked choreiform movements (p=0.66, Fisher's exact test). Both the choreiform movements and the tics waxed and waned in severity over time, with exacerbations temporally linked to streptococcal infections in a manner similar to the obsessive-compulsive symptoms.

Association Between Symptom Exacerbations and Streptococcal Infections

Evidence of a temporal relationship between streptococcal infections and symptom exacerbations was obtained from parent history, by comparison of the child's pediatric (medical) records to his or her psychiatric records, and by prospective study. Symptom onset was associated with GABHS infection in 21 children (42%), with GABHS exposure in one child (2%), and with symptoms of pharyngitis (no throat culture obtained) in 14 subjects (28%). Each child also had at least one symptom exacerbation that was preceded (within the prior 6 weeks) by a documented GABHS infection. Among the 50 children, there were a total of 144 exacerbations in which the relationship to GABHS infection was known. Thirty-three (23%) of these were not associated with any sign of GABHS infection within the preceding month. However, the majority had at least some evidence of GABHS triggers: 45 (31%) exacerbations were associated with a positive throat culture or episode of scarlet fever (which is distinguished by a maculopapular rash pathognomonic for GABHS), six (4%) had a history of recent upper respiratory infection symptoms plus known GABHS exposure (sibling or close friend), and 60 (42%) had a sore throat or upper respiratory infection symptoms with fever, but no culture or titers were obtained. The last two categories represent possible GABHS infections, but it is not possible to make such a diagnosis in the absence of a positive throat culture or rising antistreptococcal antibody titers.

DISCUSSION

The 50 children with PANDAS described in this report share many clinical features in common with other groups of childhood-onset OCD and tic disorders. The obsessive-compulsive symptoms and patterns of motor and vocal tics are similar to those previously described, as is the frequency of comorbid depression and anxiety disorders (17–19, 31, 35–37). Boys outnumber girls, as has been previously reported for both tic disorders and early-childhood onset OCD. Indeed, the PANDAS patients appear to be remarkably similar to those with prepubertal symptom onset who were previously described as part of an unselected group of subjects with childhood-onset OCD (17).

The children with PANDAS had several unique clinical characteristics, as defined by the working diagnostic criteria and confirmed by observed symptom exacerbations.

1. Very-young-age-at-onset PANDAS is defined as a prepubertal disorder so that it is not surprising that the children had an early age at onset (6.3 years for tics and 7.4 years for obsessive-compulsive symptoms). However, the average age at onset of symptoms for this group was nearly 3 years younger than that for previous groups of childhood-onset OCD and tic disorders (17, 37).

2. Symptom exacerbations were sudden and dramatic and were associated with GABHS infections. Positive throat culture was the most frequent means of demonstrating an association. Because of this, and because untreated GABHS infections can precipitate rheumatic fever, it was of concern to note how often sore throats with fever went uncultured. Because rheumatic fever continues as a risk of untreated GABHS infection, all parents should be encouraged to seek medical care whenever their school-age child has symptoms of GABHS pharyngitis, such as sore throat with fever, scarlatiniform rash, or a symptom triad of headache, stomachache, and fever (even without a sore throat).

Two clinical notes should be made. First, not all symptom exacerbations were preceded by GABHS infections; viral infections or other illnesses could also trigger symptom exacerbations. This is in keeping with the known models of immune responsivity—primary responses are specific (e.g., directed against a particular epitope on the GABHS), while secondary responses are more generalized. Thus, the lack of evidence for a preceding strep infection in a particular episode does not preclude the diagnosis of PANDAS. (Note, however, that the diagnosis cannot be made without establishing a clear association between GABHS infection and symptom exacerbation, preferably on at least two occasions.) Second, positive antistreptococcal titers obtained at the time of a single symptom exacerbation are not sufficient to prove that a child has PANDAS. Because antistreptococcal antibody titers may remain elevated for several months, longitudinal study is necessary to demonstrate that not only is seropositivity associated with symptom exacerbations, but also that seronegativity (or falling titers) is associated with symptom remission. Longitudinal study of a small number of children with PANDAS suggests that exacerbations are associated with a rapid, dramatic (twofold or higher) increase in antistreptococcal titers, while symptom remission and titer decreases occur more slowly. Data are currently being collected to further define this relationship.

3. Frequent association with motoric hyperactivity, impulsivity, and distractibility. The symptoms met criteria for ADHD, except that the onset frequently occurred after age 6 years. The children with PANDAS exhibited a peculiar “squirminess” in which the children tried very hard to sit still but constantly wriggled and fidgeted in their chairs. This was not chorea but was quite reminiscent of early descriptions of St. Vitus's dance.

4. Comorbid symptoms (emotional lability, separation anxiety, age-inappropriate behavior, and nighttime difficulties) were also episodic and temporally related to GABHS infections. The symptoms were present so frequently that it is tempting to speculate that they are also manifestations of the PANDAS phenomenon, particularly since the rates in this group of children are so much higher than expected in the community (38, 39). Perhaps the syndrome of PANDAS should be expanded to include primary diagnoses of late-onset ADHD and separation anxiety disorders, as well as OCD and tic disorders. It is possible that some or all of these may be manifestations of the pathophysiology leading to PANDAS. Further study will permit definition of the relationship between autoimmunity triggered by GABHS infection and other childhood neuropsychiatric disorders.

There are several limitations to this investigation that are worthy of note. First, many of our patients were referred through the local Tourette's Syndrome Association, which may have caused an overrepresentation of tic disorders among the study group. Epidemiologic studies and application of the PANDAS diagnostic criteria to unselected clinic populations will help ascertain whether or not tics are as common as reported here (80% of subjects). Second, the association of GABHS infection with symptom exacerbations was assigned retrospectively for the majority of episodes. Ideally, this relationship would be established by prospective analysis. For example, we established a 6-week cutoff for preceding GABHS infections. This may have excluded the triggering GABHS infection, since data from rheumatic fever studies demonstrate that the GABHS infection can precede symptom onset by several months (22, 23), although the lag between subsequent infections and symptom exacerbations is much shorter—often only a few days to a week apart. This temporal change is consistent with known models of immunity in which the primary response is slow and the secondary response is rapid (40).

The present data cannot be used to answer the question of how many children with neuropsychiatric disorders have PANDAS, nor can it inform us about the natural history of the disorder. What happens to these children? Do they comprise the one in seven individuals whose OCD and tic disorders spontaneously remit (41) because they outgrow their symptoms after they pass through the age of vulnerability? Or perhaps they are the unfortunate ones who have chronic, treatment-resistant OCD (42, 43) because repeated GABHS infections have caused irreversible damage to the basal ganglia. Answers to these questions will be obtained only by careful, systematic evaluation of this and other groups of patients with PANDAS.

We have previously speculated that obsessive-compulsive symptoms might be etiologically similar to Sydenham's chorea and rheumatic fever (5, 13). On the basis of what is known about the pathogenesis of rheumatic fever and our observations of this cohort of 50 children with PANDAS, we have developed the following model of pathogenesis of PANDAS: Pathogen + Susceptible Host ⇒ Immune Response ⇒ Sydenham's chorea or PANDAS (neuropsychiatric symptoms).

Application of the model permits the recognition of PANDAS as a distinct clinical syndrome. It also allows for the characterization of particular strains of GABHS that are prone to the induction of PANDAS in the susceptible host; the definition of factors that confer susceptibility for the development of PANDAS in an individual; the description of the immune response associated with the development of the clinical symptoms; and the identification of the structures and functions involved in the expression of the clinical symptoms. Each of the delineated points can be the focus of diagnostic testing and therapeutic intervention. The susceptible host might be rendered less susceptible by prevention of GABHS infections (antibiotic prophylaxis) or by immunization against GABHS infections. Infection of the host by pathogenic GABHS might be prevented by colonization of the host with nonpathogenic strains of the bacterium or by targeted anti-GABHS antimicrobials. The immune response might be influenced by the administration of adjuvants, cytokines, or immunomodulatory agents. End-organ pathology might be prevented by treatments aimed at removing pathogenic autoantibodies or stimulating the function of specific neural circuits or structures. Each of these arenas holds tremendous promise for future therapeutic interventions.

The possibility that pathogens other than GABHS can induce neuropsychiatric symptoms is suggested by the presence of non-GABHS-related exacerbations in the children with PANDAS, as has been reported for Sydenham's chorea (23). It is postulated that GABHS needs to be the initial autoimmunity-inciting event but that subsequent symptom exacerbations can be triggered by viruses, other bacteria, or noninfectious immunologic responses.

In the model of pathogenesis, host factors are also of critical importance. Male gender appears to be a risk factor, as three-quarters of the PANDAS subjects are male, but the mechanism of this increased vulnerability is unknown. The age of the host also may determine susceptibility; it is known that rheumatic fever is quite rare after puberty. It appears that the developmental changes of adolescence may decrease the vulnerability to the cross-reactive autoimmunity. It is also possible that the postpubertal decrease in incidence (44) is related to the fact that the rate of GABHS infections falls dramatically around the age of 12, presumably because the child has developed antibodies against the conserved portion of the M-protein (i.e., the child is able to make antibodies that recognize all strains of GABHS) (V. Fischetti, personal communication, 1994).

Genetic control of the immune response may contribute to differential vulnerability to PANDAS. Murine genetic models suggest that the response to infectious pathogens is strain specific. Different strains have responses that differ qualitatively and quantitatively and lead to very different clinical outcomes. For example, the immune response of BALB/c mice to infection with M. leprae or S. mansoni is extreme and leads to the death of the animal, whereas similar inocula in C57/BL6 mice cause self-limited infections (45, 46).

Familial factors may also play a role in the pathogenesis of PANDAS. “Rheumatogenic families,” in which the incidence of rheumatic fever far exceeds that of the general population, were described first by Cheadle in 1889 (21). Preliminary studies of the mode of inheritance of this vulnerability suggest that the trait is autosomal recessive (47, 48) and that it may be related to a surface characteristic of peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Individuals who are susceptible to rheumatic fever have a high frequency of binding of a monoclonal antibody designated D8/17 (48). We have previously reported that patients with PANDAS have rates of D8/17 positivity similar to those seen in patients with rheumatic fever (and Sydenham's chorea, a rheumatic fever variant), and markedly different from rates found in healthy control subjects (49). The presence of a biological marker of susceptibility to rheumatic fever and PANDAS provides for the development of prophylactic strategies aimed at preventing the sequelae of GABHS disease in susceptible individuals by either altering host susceptibility or preventing GABHS infection.

CONCLUSIONS

The working diagnostic criteria appear to define a meaningful subgroup of patients with childhood-onset OCD and tic disorders; with further study, other neuropsychiatric symptoms may also be found to be appropriately included in the PANDAS spectrum. The identification of a subgroup of patients with PANDAS may be important from several aspects. First, children who develop OCD, tics, motoric hyperactivity, and other neuropsychiatric symptoms as sequelae of streptococcal infections (i.e., those with PANDAS) may share a common pathogenetic process that is distinct from other (non-PANDAS) cases of such disorders. This homogeneity may be related to genetic vulnerability or other definable biological factors. Second, if children with PANDAS share a common pathogenesis, therapies can be developed that are directed at correcting the underlying pathological process, rather than at mere symptom palliation alone. Third, hypothesis-driven research directed at defining the susceptible host, the specific triggers, the host-pathogen interaction, and the end-organ targeting of the pathogenetic process may shed light not only on PANDAS, but also on non-PANDAS neuropsychiatric symptoms. Our ongoing work in the phenomenology and pathogenesis of PANDAS is designed to address each of these issues.

|

|

|

|

|

Received Aug. 26, 1996; revision received April 8, 1997; accepted May 12, 1997. From the Section on Behavioral Pediatrics, Child Psychiatry Branch, NIMH. Address reprint requests to Dr. Swedo, Child Psychiatry Branch, NIMH, Bldg. 10, Rm. 4N224, 9000 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD 20892-1381; [email protected] (e-mail). The authors thank Ms. Madeline Ramsey, Dr. Judy Rapoport, Dr. Colette Parker, Dr. Mark Schapiro, Ms. Marlene Clark, Ms. Melissa Kanter, Ms. Marge Lenane, and Mr. Dan Richter; the nursing staffs of 11East, 9West, and the Dowling Apheresis Center; and especially the patients and their parents.

FIGURE 1. Age at Onset for Boys and Girls With PANDASa (N=50)

aP ediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections.

1. Osler W: On Chorea and Choreiform Affections. Philadelphia, HK Lewis, 1894, pp 33–35Google Scholar

2. Chapman AH, Pilkey L, Gibbons MJ: A psychosomatic study of eight children with Sydenham's chorea. Pediatrics 1958; 21:582–595Medline, Google Scholar

3. Freeman JM, Aron AM, Collard JE, MacKay MC: The emotional correlates of Sydenham's chorea. Pediatrics 1965; 35:42–49Medline, Google Scholar

4. Grimshaw L: Obsessional disorder and neurological illness. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1964; 27:229–231Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Swedo SE: Sydenham's chorea: a model for childhood autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders. JAMA 1994; 272:1788–1791Google Scholar

6. Thiebaut F: Sydenham's chorea, in Handbook of Clinical Neurology, vol 8. Edited by Vinken P, Bruyn G. Amsterdam, North Holland, 1968, pp 409–436Google Scholar

7. Rapoport JL: The neurobiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder. JAMA 1989; 260:2888–2890Google Scholar

8. Goldman S, Amron D, Szliwowski HB, Detemmerman D, Goldman S, Bidaut LM, Stanus E, Luxen A: Reversible striatal hypermetabolism in a case of Sydenham's chorea. Mov Disord 1993; 8:355–358Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Giedd JN, Rapoport JL, Kruesi MJ, Parker C, Schapiro MB, Allen AJ, Leonard HL, Kaysen D, Dickstein DP, Marsh WL, Kozuch PL, Vaituzis AC, Hamburger SD, Swedo SE: Sydenham's chorea: magnetic resonance imaging of the basal ganglia. Neurology 1995; 45:2199–2202Google Scholar

10. Casey BJ, Vauss YC, Chused A, Swedo SE: Cognitive functioning in Sydenham's chorea, parts I and II: attentional processes and executive functioning. Developmental Neuropsychology 1994; 10:75–96Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Insel TR: Toward a neuroanatomy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:739–744Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Husby G, Van de Rijn I, Zabriskie JB, Abdin AH, Williams RC: Antibodies reacting with cytoplasm of subthalamic and caudate nuclei neurons in chorea and acute rheumatic fever. J Exp Med 1976; 144:1094–1110Google Scholar

13. Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Kiessling LS: Speculations on antineuronal antibody-mediated neuropsychiatric disorders of childhood. Pediatrics 1994; 93:323–326Medline, Google Scholar

14. Kiessling LS, Marcotte AC, Culpepper L: Antineuronal antibodies in movement disorders. Pediatrics 1993; 92:39–43Medline, Google Scholar

15. Swedo SE, Rapoport JL, Cheslow DL, Leonard HL, Ayoub EM, Hosier DM, Wald ER: High prevalence of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in patients with Sydenham's chorea. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:246–249Link, Google Scholar

16. Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Schapiro MB, Casey BJ, Mannheim GB, Lenane MC, Rettew DC: Sydenham's chorea: physical and psychological symptoms of St Vitus dance. Pediatrics 1993; 91:706–713Medline, Google Scholar

17. Swedo SE, Rapoport JL, Leonard HL, Lenane MC, Cheslow D: Obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents: clinical phenomenology of 70 consecutive cases. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:335–341Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Leonard HL, Lenane MC, Swedo SE, Rettew DC, Gershon ES, Rapoport JL: Tics and Tourette's syndrome: a 2- to 7-year follow-up of 54 obsessive-compulsive children. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1244–1251Google Scholar

19. Rettew DC, Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Lenane MC, Rapoport JL: Obsessions and compulsions across time in 79 children and adolescents with obsessive compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31:1050–1056Google Scholar

20. Allen AJ, Leonard HL, Swedo SE: Case study: a new infection-triggered, autoimmune subtype of pediatric OCD and Tourette's syndrome. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:307–311Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Cheadle WB: The various manifestations of the rheumatic state as exemplified in children and early life. Lancet 1889; 1:821–827Google Scholar

22. Ayoub EM, Wannamaker LW: Streptococcal antibody titers in Sydenham's chorea. Pediatrics 1966; 38:946–956Medline, Google Scholar

23. Berrios X, Quesney F, Morales A, Blazquez J, Bisno AL: Are all recurrences of “pure” Sydenham chorea true recurrences of acute rheumatic fever? Pediatrics 1985; 10:867–872Google Scholar

24. Welner Z, Reich W, Herjanic B, Jung K, Amado H: Reliability, validity, and child agreement studies of the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1987; 26:649–653Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Reich W, Cottler L, McCallum K, Corwin D, VanEerdewegh M: Computerized interviews as a method of assessing psychopathology in children. Compr Psychiatry 1995; 36:40–45Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Spitzer RL, Endicott J: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS), 3rd ed. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1982Google Scholar

27. Denckla MB: Revised neurological examination for subtle signs. Psychopharmacol Bull 1985; 21:773–793Medline, Google Scholar

28. Touwen BCL: Examination of the Child With Minor Neurological Dysfunction. Clinics in Developmental Medicine, vol 71. London, Heinemann, 1979, p 53Google Scholar

29. Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Delgado P, Heninger GR, Charney DS: The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, II: validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:1012–1016Google Scholar

30. Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, Heninger GR, Charney DS: The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, I: development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:1006–1011Google Scholar

31. Shapiro AK, Shapiro ES, Young JG, Feinberg TE: Measurements in tic disorders, in Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome, 2nd ed. New York, Raven Press, 1988, pp 451–480Google Scholar

32. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:766–771Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Murphy DL, Pickar D, Alterman IS: Methods for the quantitative assessment of depressive and manic behavior, in The Behavior of Psychiatric Patients. Edited by Burdock EL, Sudilovsky A, Gershon S. New York, Marcel Dekker, 1982, pp 355–392Google Scholar

34. Insel TR, Murphy DL, Cohen RM, Alterman I, Kilts C, Linnoila M: Obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind trial of clomipramine and clorgyline. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:605–612Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Pitman RK, Green RC, Jenike MA, Mesulam MM: Clinical comparison of Tourette's disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:1166–1171Google Scholar

36. Holzer JC, Goodman WK, McDougle CJ, Baer L, Boyarsky BK, Leckman JF, Price LH: Obsessive-compulsive disorder with and without a chronic tic disorder: a comparison of symptoms in 70 patients. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 164:469–473Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Thomsen PH, Mikkelsen HU: Course of obsessive compulsive disorder in children and adolescents: a prospective follow-up study of 23 Danish cases. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:1432–1440Google Scholar

38. Brandenburg NA, Friedman RM, Silver SE: The epidemiology of childhood psychiatric disorders: prevalence findings from recent studies. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1990; 29:76–83Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Costello EJ: Developments in child psychiatric epidemiology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1989; 28:836–841Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Roitt IM, Brostoff J, Male DK: Essential Immunology, 4th ed. Baltimore, Mosby, 1996, p 31Google Scholar

41. Karno M, Golding JM, Sorenson SB, Burnam MA: The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in five US communities. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:1094–1099Google Scholar

42. Ravizza L, Barzega G, Bellino S, Bogetto F, Maina G: Predictors of drug treatment response in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:368–373Medline, Google Scholar

43. Ackerman DL, Greenland S, Bystritsky A, Morgenstern J, Katz RJ: Predictors of treatment response in obsessive-compulsive disorder: multivariate analysis from a multicenter trial of clomipramine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1994; 14:247–254Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Huovinen P, Lahtonen R, Ziegler T, Meurman O, Hakkarainen K, Miettinen A, Arstila D, Eskola J, Saikku P: Pharyngitis in adults: the presence and coexistence of viruses and bacterial organisms. Ann Intern Med 1989; 110:612–616Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Sher A, Gazzinelli RT, Oswald IP, Clerici M, Kullberg M, Pearce EJ, Berzofsky JA, Mosmann TR: Role of T-cell derived cytokines in the down regulation of immune responses in parasitic and retroviral injection. Immunol Rev 1992; 127:183–204Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Castro AG, Minoprio P, Appleberg R: The relative impact of bacterial virulence and host genetic background on cytokine expression during Mycobacterium avium infection of mice. Immunology 1995; 85:556–561Medline, Google Scholar

47. Wilson MG, Schweitzer MD, Lubschez R: The familial epidemiology of rheumatic fever: genetic and epidemiologic studies. J Pediatr 1943; 22:468–492Crossref, Google Scholar

48. Gibofsky A, Khanna A, Suh E, Zabriskie JB: The genetics of rheumatic fever: relationship to streptococcal infection and autoimmune diseases. J Rheumatol Suppl 1991; 30:1–5Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Mittleman BB, Allen AJ, Rapoport JL, Dow SP, Kanter ME, Chapman F, Zabriskie J: Identification of children with pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections by a marker associated with rheumatic fever. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:110–112Link, Google Scholar