Posttraumatic Stress Without Trauma in Children

Abstract

Objective:

It remains unclear to what degree children show signs of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after experiencing low-magnitude stressors, or stressors milder than those required for the DSM-IV extreme stressor criterion.

Method:

A representative community sample of 1,420 children, ages 9, 11, and 13 at intake, was followed annually through age 16. Low-magnitude and extreme stressors as well as subsequent posttraumatic stress symptoms were assessed with the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment. Two measures of posttraumatic stress symptoms were used: having painful recall, hyperarousal, and avoidance symptoms (subclinical PTSD) and having painful recall only.

Results:

During any 3-month period, low-magnitude stressors occurred four times as often as extreme stressors (24.0% compared with 5.9%). Extreme stressors elicited painful recall in 8.7% of participants and subclinical PTSD in 3.1%, compared with 4.2% and 0.7%, respectively, for low-magnitude stressors. Because of their higher prevalence, however, low-magnitude stressors accounted for two-thirds of cases of painful recall and half of cases of subclinical PTSD. Moreover, exposure to low-magnitude stressors predicted symptoms even among youths with no prior lifetime exposure to an extreme stressor.

Conclusions:

Relative to low-magnitude stressors, extreme stressors place children at greater risk for posttraumatic stress symptoms. Nevertheless, a sizable proportion of children manifesting posttraumatic stress symptoms experienced only a low-magnitude stressor.

Researchers have long debated the advantages and disadvantages of relatively broad or restrictive definitions of the stressor criterion for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (1–4). Prior to DSM-IV, the stressor definition reflected the implicit view that only certain relatively rare and extreme events commonly elicit PTSD. Thus in DSM-III and DSM-III-R, the stressor criterion was defined in terms of a precipitating event with extreme, objective characteristics (5, 6). Subsequent studies challenged this view. Exposure to the extreme stressors defined by DSM-III and DSM-III-R appeared to be relatively common, occurring, for example, in approximately half of respondents in the National Comorbidity Survey (7), and such events did not invariably lead to PTSD symptoms. For example, the conditional risk for PTSD following trauma exposure was only 9.2% in the Detroit Area Survey of Trauma (8). Researchers also found that pretrauma factors moderated the risk for PTSD (7, 8). Finally, evidence suggested that milder stressors not meeting the extreme stressor definition could elicit PTSD. As a result, the stressor criterion was expanded in DSM-IV (9) and incorporated information about the individual's response to the event (4, 10).

The DSM-IV field trial (2) tested five alternative stressor definitions, ranging from a nonrestrictive criterion, in which any event that was followed by the development of criteria B, C, and D was sufficient for a PTSD diagnosis, to the more stringent DSM-III-R definition. In a community sample, rates of lifetime PTSD varied only by 3%–4% across these stressor definitions in criterion A. The authors concluded that the different stressor definitions in criterion A had “minimal impact on PTSD prevalence across all proposed criteria” and that the stressor definition should not be based on the rarity of the event. The implications for children and adolescents were unclear, since the trial included mostly adults, a few adolescents, and no children.

Several lines of evidence suggest that the response to negative events differs between children and adults. Children possess immature social and cognitive capacities that might moderate the effects of trauma or influence the expression of symptoms (11). Consistent with this possibility, a recent meta-analysis suggested that PTSD is rare in childhood, with an estimated rate of 0.6% (12). This could reflect age-related differences either in symptom expression or in stress-related vulnerability. In any case, questions arise from such data about the manner in which children respond to a range of negative events. In particular, it remains unclear to what degree children develop signs of PTSD after experiencing relatively mild stressor events below the current DSM-IV extreme stressor threshold (13–15).

Previous community-based studies examining this issue generally considered only relatively severe events meeting the DSM-IV stressor criterion (16–18). While this is understandable, inclusion of additional events would permit comparisons between such extreme stressors and other negative events of lower magnitude in terms of associated risk for PTSD symptoms. Several outcomes of such research are possible. First, consistent with the implicit approach in DSM-IV, both types of event could elicit negative outcomes, but only extreme stressors might elicit PTSD symptoms. Alternatively, both types of event could elicit both negative outcomes and PTSD symptoms, but the conditional risk from extreme stressors might be greater than that for low-magnitude negative events. Vulnerability to events might also differ as a function of pre-stress factors, as has been suggested by some (but not all [19]) previous studies (20–22).

Any study comparing response to extreme and low-magnitude stressors must grapple with the fact that people experiencing any form of traumatic event are likely to experience multiple negative events (16, 23, 24). Thus, any association between a mild stressor and PTSD symptoms could reflect the influence of a more extreme stressor that occurred earlier and might have sensitized the individual to the later milder stressor. Adult and child studies of PTSD do indeed suggest that previously exposed individuals are sensitized to the effects of subsequent trauma (16, 25, 26). However, no community-based prospective studies of youths have examined the unique effects of multiple extreme stressors on a range of negative outcomes.

In this study, we compared the strength of the association that low-magnitude and more extreme stressors manifest with PTSD symptoms (16). The study relied on a measure of PTSD symptoms but could not formally test associations with the diagnosis of PTSD, which was rare in our sample, as in previous community samples of children (12). Nevertheless, even subclinical symptoms of PTSD are important to recognize in children (27–29), since children with such symptoms do not differ significantly in terms of impairment or distress from children who meet full criteria for PTSD (29).

Method

Sample

The Great Smoky Mountains Study is a longitudinal study of the development of psychiatric and substance use disorders and need for mental health services in rural and urban youths (30, 31). In 1993, a representative sample of 1,420 children ages 9, 11, and 13 at intake was recruited from 11 counties in western North Carolina. Potential participants were selected from the population of some 20,000 children, using a household equal probability, accelerated cohort design. American Indian children were oversampled to make up 25% of the final sample. The final sample consisted of 350 Indian children (81% of those recruited) and 1,070 non-Indian children (80% of those recruited); of the latter, 92.5% were white and 7.5% were African American. In the analyses, each individual's contribution was weighted proportionately to the probability of selection into the study, so that the results are representative of the whole population of children of this age. The average response rate over the several assessment waves was 83%. Attrition and nonresponse did not differ among the groups considered here and were not associated with psychiatric status. In this article, we present data on 6,674 parent-child pairs of interviews carried out across the child age range of 9–16 years.

Procedure

Children and their primary caregivers (the biological mother 83% of the time) were interviewed separately in their homes or another convenient location by trained interviewers who were residents of the study area. Interviewers were trained by Department of Social Services staff in the requirements for reporting abuse or neglect. Before the interviews began, parent and child signed informed consent or assent forms approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Extreme stressors, other negative events, and associated posttraumatic stress symptoms were assessed using the life events and posttraumatic stress sections of the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (32). The life events section includes 17 potentially traumatic events (i.e., those meeting DSM-IV PTSD criterion A “extreme stressors,” such as physical abuse and violent death of a loved one) and 15 events that do not meet criterion A and have commonly been associated with anxiety or depression in children (33, 34). The parent or child was queried about the occurrence of each event within the past 3 months and when it occurred. Criterion A events were also assessed for lifetime occurrence. A reliability study with 58 parents and children interviewed twice by different interviewers found fair to excellent test-retest reliability (intraclass correlations ranged from 0.58 to 0.83, depending on the informant and the type of event) (34). A list of events and 3-month prevalence rates was presented in a previous publication (35).

For each event, the interviewer asked screening questions to determine whether the three key symptom clusters of PTSD (painful recall, avoidance, and hyperarousal) were present during the past 3 months and were linked to the event under discussion. Painful recall/reexperiencing was assessed first, and if it was endorsed, the interviewer inquired about avoidance and hyperarousal. Painful recall/reexperiencing is defined as unwanted, painful, and distressing recollections, memories, thoughts, or images of the event. In young children, this might involve repetitive play, trauma-specific reenactment, or nightmares. This procedure was used to avoid false positives and to reduce the length of the interview (32). If at least minimal or higher levels of all three symptoms were endorsed, then the detailed PTSD module was completed. Because few children met full diagnostic criteria for PTSD, two measures of PTSD symptoms were used: endorsing the presence of symptoms of painful recall, hyperarousal, and avoidance, which was defined as subclinical PTSD, and endorsing painful recall only.

Analyses

Prevalence estimates, odds ratios, and group comparisons were computed using the PROC GENMOD program of the SAS software package (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.) with the general estimation equations option to account for both the sampling design and within-subject correlations. Robust variance estimates (i.e., sandwich-type estimates) were used, together with sampling weights, to adjust the standard errors of the parameter estimates to account for the multiphase sampling design. The use of multiwave data with the appropriate sample weights thus capitalized on the multiple observation points over time while controlling for the effect on variance estimates of repeated measures.

Results

Prevalence

Table 1 lists 3-month prevalence estimates for both low-magnitude and extreme stressors and the two event-related outcomes—painful recall only and subclinical PTSD. The rates for the event-related outcomes are base rates, considering all children in the sample, and therefore are not conditional on event exposure. During any 3-month period, about four times more children reported a low-magnitude stressor than an extreme stressor (24.0% versus 5.9%, p<0.001). This 4:1 ratio for low-magnitude relative to extreme stressor exposures, however, was not reflected in the outcome data (Table 1). Despite the markedly greater rate of low-magnitude stressors, painful recall associated with low-magnitude stressors was only twice as common as painful recall associated with extreme stressors (1.0% compared with 0.5%, p<0.02). Moreover, low-magnitude and extreme stressors were associated with similar numbers of children with subclinical PTSD (0.2% in both cases), despite the markedly higher rate of low-magnitude stressors. Thus, while low-magnitude stressors occur far more commonly than extreme stressors, these data suggest that they are far less likely to be associated with symptoms. Nevertheless, because of their high prevalence, low-magnitude stressors accounted overall for 68.9% of cases of painful recall and 47.9% of cases of subclinical PTSD.

| Group or Subgroup | Low-Magnitude Stressors | Extreme Stressors | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | Painful Recall | Subclinical PTSD | Event | Painful Recall | Subclinical PTSD | |||||||

| % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | |

| Total | 24.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 5.9 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Female | 25.0 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 5.9 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Male | 23.2 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 6.0 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 9–13 years | 21.8 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 4.8 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 14–16 years | 25.7 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 6.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

TABLE 1. Comparison of 3-Month Prevalence Estimates of Low-Magnitude Stressors, Extreme Stressors, Painful Recall, and Subclinical PTSD in 1,420 Children and Adolescentsa

The consistency of this general pattern was compared across gender and age groups. Both types of stressor events were slightly more common in adolescence than in childhood (low-magnitude stressors: odds ratio=1.2, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.0–1.4, p=0.03; extreme stressors: odds ratio=1.4, 95% CI=1.0–2.0, p=0.05). Subclinical PTSD with extreme stressors was more common in adolescence (odds ratio=5.4, 95% CI=1.2–23.2, p=0.02), but rates of all other PTSD outcomes were invariant with age. Although rates of events did not vary by gender, girls had higher rates of both PTSD-related outcomes. Subclinical PTSD following low-magnitude stressors was much more common in girls than in boys (odds ratio=7.1, 95% CI=1.2–43.1, p=0.03), although the base rates for both boys and girls were below 0.5%.

Conditional Rates

Table 2 presents the rates for various outcomes only for children who reported exposure to a stressor—that is, conditional rates for the various outcomes. Low-magnitude stressors produced more cases of children with PTSD-related symptoms than did extreme stressors because of the high rate of low-magnitude stressors. However, the less common high-magnitude events were more potent predictors of symptoms: conditional rates were significantly higher for extreme relative to low-magnitude stressors (painful recall: 8.7% compared with 4.2%, p=0.05; and subclinical PTSD: 3.1% compared with 0.7%, p<0.03). Girls were generally more vulnerable to both types of negative events. After extreme stressors, girls were more likely than boys to develop painful recall (odds ratio=3.1, 95% CI=1.1–9.1, p=0.04). Similarly, for low-magnitude stressors, girls also had higher rates than boys for subclinical PTSD (odds ratio=6.5, 95% CI=1.0–40.9, p=0.04) but not for painful recall. There were no differences for either outcome by age.

| Group or Subgroup | Low-Magnitude Stressors | Extreme Stressors | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Painful Recall | Subclinical PTSD | Painful Recall | Subclinical PTSD | |||||

| % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | |

| Total | 4.2 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 8.7 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 1.3 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 5.0 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 13.2 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 1.7 |

| Male | 3.4 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 4.9 | 2.2 | 2.9 | 2.1 |

| Age | ||||||||

| 9–13 years | 3.9 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 8.7 | 3.1 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| 14–16 years | 4.4 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 8.4 | 2.7 | 5.2 | 2.5 |

TABLE 2. Conditional Probabilities for Painful Recall and Subclinical PTSD for Low-Magnitude Stressors and Extreme Stressors in 1,420 Children and Adolescentsa

Not all low-magnitude stressor events had similar conditional rates. Some events almost never resulted in subsequent symptoms (conditional risk <1.0%; e.g., a new child in home, moving house), whereas risks associated with others were similar to or greater than the average response to extreme stressor events. In terms of painful recall, such high-risk, low-magnitude stressors included death of a loved one (6.5%; SE=5.1), parental separation (9.1%; SE=4.8), breaking up with a best friend (9.0%; SE=4.0), or breaking up with a boyfriend or girlfriend (6.6%; SE=2.8). Similarly, cases of subclinical PTSD in response to low-magnitude stressors were almost entirely accounted for by parental separation (4.1%; SE=3.5), breaking up with a best friend (2.1%; SE=2.1), and breaking up with a boyfriend or girlfriend (1.5%; SE=1.3). (A full list of conditional rates for both outcomes for each of the low-magnitude events is available on request from the first author.)

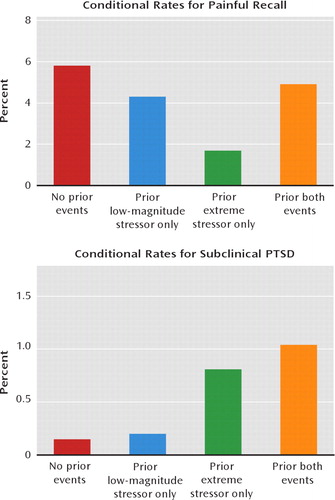

Multiple Exposures

Children also were assessed for prior stress exposure. Exposure to multiple stressor events was common. Of those with a recent low-magnitude stressor, 17.4% (SE=1.5) reported no prior extreme stressor or low-magnitude stressor, 13.0% (SE=1.6) reported prior low-magnitude stressors only, 23.6% (SE=1.6) reported only prior extreme stressors, and 38.2% (SE=2.2) reported prior exposure to both extreme stressors and low-magnitude stressors. It is plausible that most symptomatic children exposed to recent low-magnitude stressors had also experienced prior exposure to extreme stressors. This possibility was evaluated, as shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Effect of Prior Event Exposures on Response to a Recent Low-Magnitude Eventa

aChildren who reported only a prior extreme stressor had significantly lower rates of painful recall following a recent lower-magnitude event than those who had no prior exposures or exposure to both types of event.

Figure 1 displays conditional risks for painful recall and subclinical PTSD after exposure to low-magnitude stressors. Even children with no prior exposure to an extreme stressor displayed PTSD symptoms. Exposure to a prior extreme stressor did not further increase risk for painful recall or subclinical PTSD. This result, however, could be influenced by the time interval between the events, such that extreme stressors occurring in the distant past do not modulate the relationship between more recent low-magnitude stressors and symptoms. We evaluated this possibility in logistic regression models predicting PTSD symptoms following low-magnitude stressors. In each model, predictors were included for both types of stressor occurring in the recent past (<1 year ago) or the distant past (>1 year ago). Results for these models are presented in Table 3. The models show that recent extreme stressors did increase risk for both types of posttraumatic stress following low-magnitude stressors.

| Variablea | Painful Recall | Subclinical PTSD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

| Distant extreme stressor | 0.3* | 0.1–0.6 | 1.2 | 0.3–4.1 |

| Distant low-magnitude stressor | 1.6 | 0.7–3.6 | 1.4 | 0.8–2.4 |

| Recent extreme stressor | 3.0* | 1.0–9.2 | 6.2* | 1.4–27.2 |

| Recent low-magnitude stressor | 1.9 | 0.8–4.4 | 1.8 | 0.5–6.0 |

TABLE 3. Regression Models Predicting Conditional Risk for PTSD Symptoms Following a Low-Magnitude Stressor From Prior Exposuresa

Discussion

PTSD is one of the few DSM-IV disorders defined by its etiology. As such, the definition of the stressor criterion constrains the scope of the diagnosis. Among individuals exposed to low-magnitude stressors, a small proportion displayed PTSD symptoms compared with those exposed to extreme stressors. Nevertheless, because low-magnitude stressors are far more common than extreme stressors, they generated a greater proportion of the negative outcomes among the children in this study, accounting for half of those with subclinical PTSD and two-thirds of those reporting painful recall only. For most of the children who developed PTSD symptoms after exposure to low-magnitude stressors, the symptoms followed interpersonal loss: death of a loved one, parental separation, breakup with a best friend, or breakup with a boyfriend or girlfriend. Thus, while extreme stressors were the more potent risk factors for PTSD symptoms, low-magnitude stressors accounted for a significant portion of children with symptoms.

Many children had experienced multiple stressors over their lifetime, and most children who developed PTSD symptoms after low-magnitude stressor events had also experienced extreme stressors. Extreme stressors occurring more than a year before the recent event tended to have little impact on risk, but recent extreme stressors increased the risk threefold to sixfold after subsequent low-magnitude events. These findings are only partially consistent with data from adult samples (25, 26), although both sets of findings emphasize the impact of recent stressors.

One goal of this study was to inform efforts to classify antecedents of traumatic stress in children. A few recommendations are warranted. First, our results support the need to clearly distinguish extreme and low-magnitude stressors, since the risk for stress-related symptoms is distinctly higher with extreme stressors. At the same time, our results also suggest the importance of recognizing the risk associated with low-magnitude stressors. Although such events have a lower conditional probability of predicting PTSD symptoms than do extreme stressors, they have a high prevalence. Moreover, the relatively modest risk of low-magnitude stressors increases when children exposed to mild stress also have a history of significant stress within the past year as well as for those who have a prior history of anxiety and an adverse family environment (16). Thus, determining a child's relative risk for PTSD symptoms should involve consideration of the event type, recent event history, and developmental context.

This study compared the sequelae of different types of stressful events, yet very few children in the study met criteria for full-blown PTSD. This is clearly not because of lack of event exposure, since the majority of children had been exposed to an extreme stressor by age 16. The most likely explanation is that the DSM-IV cutoffs for criteria B, C, and D were derived from studies of adults, and the optimal algorithm for PTSD in children may require substantially fewer symptoms (27–29). This is an issue currently under study for DSM-5. A number of other epidemiologic samples of PTSD in childhood have reported similarly low rates (16, 36, 37; see references 18 and 38 for population-based studies with higher rates). It is also possible, however, that the lower rates of PTSD are attributable to our use of screening questions. Participants had to display at least one general symptom from each symptom cluster (i.e., painful recall, hyperarousal, and avoidance) to proceed to the full PTSD module. For example, the screen for painful recall probes for unwanted, painful, and distressing recollections, memories, thoughts, or images of the life event (including repetitive play or trauma-specific reenactment). This screen overlaps with the first three symptoms listed in criterion B, but not the last two. Therefore, some children may have met criterion B based on the symptoms not assessed. The use of screens likely results in a modest reduction in the study's sensitivity to detect full-blown PTSD.

At the same time, the same screen structure was used after low-magnitude stressors and extreme stressors. Thus, even if our estimates for overall PTSD symptoms are low, this would have affected the groups with extreme stressors and low-magnitude stressors equally. Thus our primary conclusion that cases of posttraumatic stress symptoms may be underidentified with a strict application of the A1 criterion would not have been affected by use of the screen. It is also important to note that few studies can evaluate the stressor criterion because most began after publication of DSM-IV and thus only assess for PTSD symptoms after those events already codified in the stressor criterion. This study is unusual in its ability to inform our understanding of the differential effects of high-magnitude versus low-magnitude stressor events in children, even if it cannot usefully speak to the risk for full-blown PTSD and may underestimate rates of PTSD symptoms overall.

Conclusions

PTSD is a relatively new addition to DSM, only appearing in 1980 (6). Since that time, much work has been done to better understand the risk for posttraumatic symptoms in adult community samples (7, 25, 39), but research on PTSD in children has often focused on clinical samples or groups of children exposed to a single traumatic event. This study supports the DSM-IV extreme stressors as most likely to elicit posttraumatic stress symptoms, but it also suggests as a troubling public health concern that many, if not most, children experiencing significant levels of posttraumatic stress or PTSD symptoms will be unidentified if we fail to assess the impact of low-magnitude stressors.

1. : What constitutes a stressor? the “criterion A” issue, in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: DSM-IV and Beyond. Edited by Davidson JRTFoa E. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993, pp 37–54Google Scholar

2. : The posttraumatic stress disorder field trial: evaluation of the PTSD construct: criteria A through E, in DSM-IV Sourcebook. Edited by Widiger TPincus HAFirst MBRoss RDavis W. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1998, pp 803–844Google Scholar

3. : The stressor criterion in the DSM-IV posttraumatic stress disorder: an empirical investigation. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 50:699–704Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. : Life events and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: the intervening role of locus of control and social support. Mil Psychol 1990; 2:241–256Crossref, Google Scholar

5.

6.

7. : Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:1048–1060Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. : Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:626–632Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9.

10. : Post-traumatic stress disorder in the general population: findings of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Survey. N Engl J Med 1987; 317:1630–1634Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. : Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychol Bull 2001; 127:87–127Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Committee on the Prevention of Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse Among Children and Young Adults (Research Advances and Promising Interventions): Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2009Google Scholar

13. : Assessment of psychosocial experiences in childhood: methodological issues and some illustrative findings. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1993; 34:879–897Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. : Stressful life events in depressed adolescents: the role of dependent events during the depressive episode. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:591–598Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. : Life events in early adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1987; 26:865–872Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. : Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007; 64:577–584Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. : Prevalence of PTSD in a community sample of older adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37:147–154Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. : Traumas and posttraumatic stress disorder in a community population of older adoles-cents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:1369–1380Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. : Puberty and depression, in Gender Differences at Puberty. Edited by Hayward C. New York, Cambridge University Press, 2003, pp 137–164Crossref, Google Scholar

20. : Maternal depressive symptoms and depressive symptoms in adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1995; 36:1161–1178Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. : Adolescent depression: why more girls? J Youth Adolesc 1991; 20:247–271Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. : The influence of genetic factors and life stress on depression among adolescent girls. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:225–232Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. : Longitudinal course of posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in a community sample of adolescents and young adults. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:1320–1327Link, Google Scholar

24. : Prevalence and comorbidity of traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in adolescents and young adults, in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Lifespan Developmental Perspective. Edited by Maercker ASchützwohl MSolomon Z. Seattle, Hogrefe & Huber, 1999, pp 113–133Google Scholar

25. : Previous exposure to trauma and PTSD effects of subsequent trauma: results from the Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:902–907Link, Google Scholar

26. : Post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: an epidemiological study. Psychol Med 1991; 21:713–721Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. : Toward establishing procedural, criterion, and discriminant validity for PTSD in early childhood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40:52–60Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. : New findings on alternative criteria for PTSD in preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42:561–571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. : Toward an empirical definition of pediatric PTSD: the phenomenology of PTSD symptoms in youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41:166–173Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. : Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psy-chiatry 2003; 60:837–844Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. : The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth: goals, design, methods, and the prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:1129–1136Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. : Life events and post-traumatic stress: the development of a new measure for children and adolescents. Psychol Med 1998; 28:1275–1288Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. : Life events and affective disorder: replications and limitations. Psychosom Med 1993; 55:248–259Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. : Recent life events and psychiatric disorder in school age children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1990; 31:839–848Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. : The prevalence of potentially traumatic events in childhood and adolescence. J Trauma Stress 2002; 15:99–112Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. : The British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey, 1999: the prevalence of DSM-IV disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42:1203–1211Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. : Prevalence rates and correlates of psychiatric disor-ders among preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:204–214Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. : Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: results from the National Survey of Adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol 2003; 71:692–700Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. : Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:216–222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar