Cognition in Schizophrenia

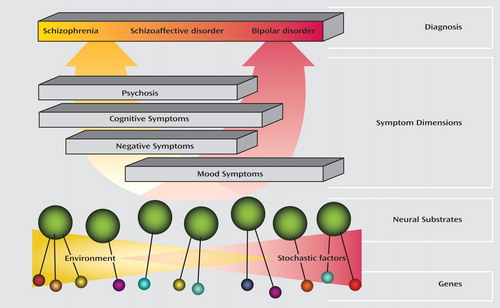

Reliable, broadly-shared diagnostic criteria are necessary for good clinical care as well as for research; otherwise, no two patient samples would be comparable. A challenge for the field of psychiatry has been the need to formulate shared diagnostic criteria despite the early stage of the relevant science and the lack of objective laboratory tests. Lacking biological guideposts, community consensus has played an outsized role in the development of diagnostic criteria and has made it difficult to justify change. There is a fine balance between the useful updating of diagnostic criteria and unleashing of diagnostic confusion. Overall, however, the reification of DSM criteria intended as provisional has impeded research and treatment development. For example, the criteria for schizophrenia, beginning with DSM-III, emphasize psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions, and make no mention of cognitive symptoms, such as working memory deficits. Although the cognitive symptoms are both highly disabling and resistant to existing treatments, there was little incentive for industry to develop new drugs because there was no recognized indication for which they could gain approval. One possible way to target serious orphan symptoms was to “deconstruct” disorders into symptom complexes that might have different neural and etiological substrates. Schizophrenia might usefully be deconstructed into the following four clusters of symptoms: positive, negative, cognitive, and mood. Moreover, these symptoms might best be understood as dimensions continuous with the “normal” state—many nonpsychotic relatives of individuals with schizophrenia have milder forms of the cognitive abnormalities as well as the correlated structural and functional deficits observed with neuroimaging. The strategy was to focus treatment development not on existing DSM-IV entities but on dimensions, such as the cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia, in which compelling hypotheses existed about the underlying neural circuitry and pharmacology. Led by the late Wayne Fenton, M.D., the National Institute of Mental Health developed the Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) project focused on developing treatment for the cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia. The goal was to facilitate broad academic, industry, and regulatory (Food and Drug Administration) agreement that cognitive symptoms could be a treatment indication and to develop measures by which treatment efficacy could be judged. MATRICS has now generated a working consensus with the result that a significant number of clinical trials have been initiated. As the science progresses, we should be opportunistic in identifying neural pathways that might give rise to significant symptoms even if they do not conform precisely to our current classification. Identification of neural circuits points the way to cells and synapses and thus molecular targets that could lead to novel therapies.