The Effects of Resident Work-Hour Regulation on Psychiatry

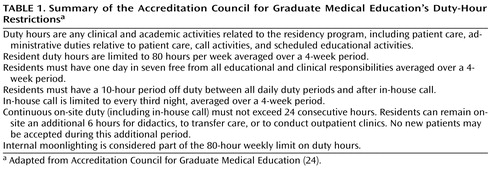

In 1984, after the death of Libby Zion, who died shortly after assessment for fever in a New York City emergency department, a Manhattan district attorney and grand jury suggested that overworked and inadequately supervised residents, a product of systemic problems with resident physician education, might have contributed to her death (1) . Based on grand jury recommendations, the Ad Hoc Advisory Committee on Emergency Services, together with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the Committee of Interns and Residents, and the American College of Surgeons, enacted local regulations stipulating that residents work no more than 80 hours per week, no more than 24 consecutive duty hours at a time, and no more than 12-hour shifts in the emergency department and that they have at least one 24-hour period off every 7 days (2 , 3) . Subsequently, the ACGME implemented new duty-hour standards for all residency programs, effective July 1, 2003 (4) ( Table 1 ).

The intentions of the ACGME work-hour restrictions, emphasized by their supporters (5) , were to reduce medical errors associated with house staff fatigue and to improve resident education and well-being. Critics argue that the restrictions could result in less continuity of care for patients, a decrease in the number of procedures residents perform during training, and, possibly, a decrease in professionalism tied to the fact that residents might feel less responsibility toward their patients when they leave the hospital at the end of a shift (1 , 6 , 7) .

Effects of Duty-Hour Restrictions

Although several studies have examined patient outcomes following the initiation of duty-hour restrictions, methodological weaknesses limit the conclusions that can be drawn in these studies about the impact of work-hour restrictions on patient care. Most studies have been restricted to single training sites and have understandably been unable to conduct randomized trials or control for the numerous factors that affect year-to-year changes in quality of practice (8 – 10) . Two large-scale studies have attempted to address some of these issues. One found no increased mortality among Medicare patients related to resident duty-hour restrictions (11) , and the other noted some evidence for reduced mortality among patients with selected medical but not surgical conditions in 131 Veterans Administration teaching hospitals during the second year, but not the first year, after implementation of the reforms (12) . However, even these temporally associated findings may well be due to factors other than changes in resident work-hour patterns (13) .

The second primary goal of duty-hour restrictions was to further resident education and guard against resident fatigue due to sleep deprivation. Research has documented the negative impact of sleep deprivation and high call frequency on resident physicians (14 , 15) . A nationwide prospective study concluded that interns were twice as likely to have motor vehicle accidents and five times as likely to have near-miss incidents after extended work shifts (>24 hours) than after nonextended shifts (16) . Another study, comparing functional impairment after long work hours (80–90 hours per week with overnight call every fourth or fifth night) with impairment associated with alcohol ingestion (0.04–0.05 mg per 100 ml of blood), concluded that reaction times on the Psychomotor Vigilance Test, omission errors on the Continuous Performance Test, and car crashes on a simulated driving task were similar between the two groups (17) .

The impact of work-hour regulation has been most noticeable, as expected, in surgical programs. In one study following implementation of duty-hour restrictions, residents reported improved quality of life, decreased burnout, increased ability to maintain significant relationships, increased motivation to work, and an improvement in American Board of Surgery In-Training Examination scores, while preserving or even increasing the volume of surgical cases in which they participated. Conversely, attending surgeons in this study felt that the duty-hour restrictions worsened their own quality of life, decreased the quality of patient care, and rendered the quality of training of future surgeons “somewhat worse” (18) . But there are trade-offs. As Dr. Kara Worley, a resident in obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, reflected: “The long hours suck. But the unwritten resident motto is ‘It’s better to work 100 hours/week for 4 years than to stay an extra year and do only 80 hours/week.’”

Although restrictions prohibit internal moonlighting, there is no prohibition against external moonlighting, which can also affect residents’ performance and well-being. Whether this activity has increased as residents work fewer hours in their own programs is unknown.

Work-Hour Regulations and Psychiatric Residents

We posted a query on the listserv of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training soliciting experiences and views regarding the impact of resident work-hour regulation on psychiatry. We received detailed responses from 11 highly experienced residency training directors from a diverse assortment of programs across the nation. We also solicited the experiences and opinions of residents in our own program and in several other programs as well as through a chief residents’ national forum. In contrast to the experiences of many surgical and some primary care and pediatric subspecialty programs, for many decades psychiatric training programs have rarely if ever required residents to work 80 hours or more per week. The major impact of work-hour regulation in psychiatry has resulted from the continuous on-site duty rule that limits residents to 24 consecutive hours of patient care with up to an additional 6 hours available to participate in didactics and to transfer care of patients, and from the requirement that residents have at least 10 hours off between shifts.

The consensus of those responding was that the duty-hour rules have had a positive effect on the well-being of psychiatric residents. Rest, sleep, and time for families are good things. As Sidney Zisook, training director at University of California, San Diego, put it, “The regulations provide the training directors with the ammunition they need to insist that faculty provide more humane conditions for the residents. You can always blame the ‘damn ACGME’ but still see that residents get out by 2 p.m. the day after call. The residents are healthier.”

Didactic teaching and educational conferences have indeed been affected by the 24-plus-6-hour rule. Postcall residents may miss classes, causing conflicts with the ACGME’s Residency Review Committee rule mandating that residents attend at least 70% of required seminars. In response to these conflicting requirements, some programs have reworked schedules for morning rounds and didactic conferences to accommodate the new rules. Furthermore, residency programs are now being constructively challenged to create pedagogical alternatives to traditional lecture and seminar series, and even to conjure up educational activities that permit learners to engage their subject matter asynchronously and to demonstrate competencies in ways other than simply showing up to class.

Opinions vary regarding how “professionalism” in psychiatric residents might be affected by strict adherence to the 24-plus-6-hour rule. Christopher Kenedi, a chief resident at Duke University, expressed the following concerns: “Each generation seems to tap their watches a little more and look at the clock rather than the patient. It is moving us more toward system-based care with a focus on shift work and better handoffs and sign-outs rather than better care and education.” Along these lines, Marshall Forstein, training director at the Cambridge Hospital-Harvard program, mused, “I do think that there is a way in which rigid rules eat away at the concept of being a professional who does what is necessary until the job is done. I do think that we have seen an erosion of ‘ownership’ of clinical responsibility and a frustration on the part of residents who try to do what is right.”

Although, as Joan Anzia, training director at Northwestern University, pointed out, “a sense of entitled apathy did exist in some residents well before duty-hour regulations,” most respondents generally agreed that the majority of residents, highly professional, often feel trapped in ethical binds when the regulations require them to leave before they have completed their work to their own standards and satisfaction. Several respondents described residents who felt sufficiently rested during a call night who wished to stay at work to see patients or complete certain tasks after their 24-plus-6-hour shifts had expired. But training directors, increasingly preoccupied with how “fanatically rigid” accrediting bodies have become about adhering to “time clocks,” are obliged to force residents to leave anyway, because of what John Urbach, of Virginia Commonwealth University, portrayed as a “compliance trumps everything” mentality.

Impact on Faculty and Patient Care

Training directors report diverse reactions from faculty. Whereas some faculty members are sympathetic to the changing expectations of residents, others, recalling their own unregulated work-hour training conditions, are less compassionate, particularly if their personal workloads and coverage requirements have increased as a result of the new regulations. Several psychiatrists who trained before work-hour restrictions recalled having great difficulty keeping awake in psychotherapy sessions during afternoons following nights on call. Indeed, several recalled being instructed by supervisors to discretely pinch their thighs or bite the insides of their cheeks to help stay awake during sessions. Although no data exist, who would argue that rested residents don’t render better care?

Given that very short hospital stays and “hospitalist” systems already assure that “teams” deliver most inpatient and crisis treatment, could psychiatric patient care additionally suffer as a result of inadequate handoffs and sign-outs between residents resulting from the 24-plus-6-hour rule? A recent survey of 202 internal medicine residency programs showed that 55% were inconsistent in requiring sign-outs at transfers of care, 34% left sign-outs solely to interns, 59% did not involve nursing staff in the sign-out process, and 60% of the programs did not provide any education or workshops on developing sign-out skills (19) . Several health care systems using computerized sign-out systems in internal medicine and surgery have reported reductions in medical errors and improved continuity of patient care (20 , 21) . One report demonstrated how electronic personal digital assistants (PDAs) might facilitate sign-outs between psychiatric residents on clinical services (22) . As the number of continuous duty hours decreases, the number of handoffs required will increase. As underscored by Sidney Weissman, former psychiatric residency training director at Northwestern University, “Something is usually lost when this occurs.… We need further work on how to transfer patient information and maintain the integrity of care. In football, too many handoffs result in fumbles.”

Future Considerations

Effects of work-hour restrictions on the administrative and financial operations of academic departments are still surfacing. Christopher Varley, child psychiatry training director at the University of Washington, noted that as surgical and medical specialties are requesting increased house staff allotments to compensate for the work-hour restrictions, psychiatry departments encounter greater difficulties in obtaining new positions. “The playing field has become increasingly competitive.” Furthermore, such competition may ultimately affect recruitment of medical students into psychiatry; to the extent that lifestyle issues determine medical students’ specialty choices (23) , as work-hour restrictions render other medical and surgical residencies and ultimately their professions more humane, could psychiatric training become relatively less attractive?

1. Wallack MK, Chao L: Resident work hours: the evolution of a revolution. Arch Surg 2001; 136:1326–1331Google Scholar

2. Steinbrook R: The debate over resident’s work hours. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:1296–1300Google Scholar

3. NY State Codes Rules & Regs § 405.43 (b) (6) (1989)Google Scholar

4. Philibert I, Friedmann P, Williams WT: New requirements for resident duty hours. JAMA 2002; 288:1112–1114Google Scholar

5. Lund KJ, Teal SB, Alvero R: Resident job satisfaction: one year of duty hours. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005; 193:1823–1826Google Scholar

6. Hutter MM, Kellogg KC, Ferguson CM, Abbott WM, Warshaw AL: The impact of the 80-hour resident workweek on surgical residents and attending surgeons. Ann Surg 2006; 243:864–875Google Scholar

7. Drazen JM, Epstein AM: Rethinking medical training: the critical work ahead. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:1271–1272Google Scholar

8. Horwitz LI, Kosiborod M, Lin Z, Krumholz HM: Changes in outcomes for internal medicine inpatients after work-hour regulations. Ann Intern Med 2007; 147:97–103Google Scholar

9. Landrigan CP, Rothschild JM, Cronin JW, Kaushal R, Burdick E, Katz JT, Lilly CM, Stone PH, Lockley SW, Bates DW, Czeisler CA: Effect of reducing interns’ work hours on serious medical errors in intensive care units. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:1838–1848Google Scholar

10. Poulose BK, Ray WA, Arbogast PG, Needleman J, Buerhaus PI, Griffin MR, Abumrad NN, Beauchamp RD, Holzman MD: Resident work hour limits and patient safety. Ann Surg 2005; 241:847–856Google Scholar

11. Volpp KG, Rosen AK, Rosenbaum PR, Romano PS, Even-Shoshan O, Wang Y, Bellini L, Behringer T, Silber JH: Mortality among hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries in the first 2 years following ACGME resident duty hour reform. JAMA 2007; 298:975–983Google Scholar

12. Volpp KG, Rosen AK, Rosenbaum PR, Romano PS, Even-Shoshan O, Canamucio A, Bellini L, Behringer T, Silber JH: Mortality among patients in VA hospitals in the first 2 years following ACGME resident duty hour reform. JAMA 2007; 298:984–992Google Scholar

13. Meltzer DO, Arora VM: Evaluating resident duty hour reforms: more work to do. JAMA 2007; 298:1055–1057Google Scholar

14. Steele MT, Ma OJ, Watson WA, Thomas HA, and Muelleman RL: The occupational risk of motor vehicle collisions for emergency medicine residents. Acad Emerg Med 1999; 6:1050–1053Google Scholar

15. Papp KK, Stoller EP, Sage P, Aikens JE, Owens J, Avidan A, Phillips B, Rosen R, Strohl KP: The effects of sleep loss and fatigue on resident-physicians: a multi-institutional, mixed-method study. Acad Med 2004; 79: 394–406Google Scholar

16. Barger LK, Cade BE, Ayas NT, Cronin JW, Rosner B, Speizer FE, Czeisler CA: Extended work shifts and the risks of motor vehicle crashes among interns. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:125–134Google Scholar

17. Arnedt JT, Owens J, Crouch M, Stahl J, Carskadon MA: Neurobehavioral performance of residents after heavy night call vs after alcohol ingestion. JAMA 2005; 294:1025–1033Google Scholar

18. Bland KI, Stoll DA, Richardson JD, Britt LD; Members of the Residency Review Committee-Surgery: Brief communication of the Residency Review Committee-Surgery (RRC-S) on residents’ surgical volume in general surgery. Am J Surg 2005; 190:245–250Google Scholar

19. Horwitz LI, Krumholz HM, Green ML, Huot SJ: Transfers of patient care between house staff on internal medicine wards. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:1173–1177Google Scholar

20. Petersen LA, Orav EJ, Teich JM, O’Neill AC, Brennan TA: Using a computerized sign-out program to improve continuity of inpatient care and prevent adverse events. Jt Comm J Qual Improv 1998; 24:77–87Google Scholar

21. Van Eaton EG, Horvath KD, Lober WB, Rossini AJ, Pellegrini CA: A randomized controlled trial evaluating the impact of a computerized rounding and sign-out system on continuity of care and resident work-hours. J Am Coll Surg 2005; 200:538–545Google Scholar

22. Luo J, Hales RE, Servis M, Gill M: Clinical computing: use of personal digital assistants in consultation psychiatry. Psychiatr Serv 2002; 53:271–272, 279Google Scholar

23. Dorsey ER, Jarjoura D, Rutecki GW: Influence of controllable lifestyle on recent trends in specialty choice by US medical students. JAMA 2003; 290:1173–1178Google Scholar

24. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education: Duty Hours Language. July 3, 2003. www.acgme.org/acwebsite/dutyhours/dh_lang703.pdfGoogle Scholar