Circadian Rhythm of Salivary Cortisol in Holocaust Survivors With and Without PTSD

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors’ goal was to determine whether cortisol circadian rhythm alterations observed in younger subjects with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are also present in geriatric trauma survivors with PTSD. METHOD: Salivary cortisol levels were measured at six intervals from awakening until bedtime in 23 Holocaust survivors with PTSD, 19 Holocaust survivors without PTSD, and 25 subjects who had not been exposed to the Holocaust. Thirty-three of the subjects were men, and 34 were women. RESULTS: Cortisol levels were significantly lower at awakening, at 8:00 a.m., and at 8:00 p.m. in Holocaust survivors with PTSD than in nonexposed subjects, resulting in a flatter circadian rhythm, similar to what has been observed in aging but different from what has been reported in younger subjects with PTSD. CONCLUSIONS: These data provide evidence of differential neuroendocrine alterations in geriatric PTSD.

Alterations of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis associated with normal aging are generally opposite to those reported in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Aging has been associated with diminished negative feedback inhibition and elevated cortisol levels (1), but increased negative feedback inhibition and normal-to-reduced levels of cortisol have been observed in PTSD (see, e.g., reference 2 for review).

One of the earliest observable HPA abnormalities in aging is a rise in cortisol levels during the circadian trough, resulting in a flatter circadian rhythm (1, 3). Compared with subjects without PTSD, veterans with PTSD showed a greater diurnal range owing to a reduced trough in cortisol release (4), a finding confirmed in civilian PTSD (5). Thus, it is of interest to examine whether and to what extent PTSD abnormalities in older subjects are maintained in the face of aging or whether the effects of aging become superimposed on the PTSD effects.

The present study examined whether there are changes in the patterning of cortisol release suggestive of changes in the circadian rhythm of cortisol in aging Holocaust survivors with and without PTSD compared with demographically comparable subjects not exposed to the Holocaust.

Method

Holocaust survivors with and without PTSD and Jewish adults who had not experienced the Holocaust and who had no major axis I disorder were studied. Individuals with a history of psychosis, bipolar disorder, substance dependence, dementia, or major medical illness were excluded. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine; all subjects provided written, informed consent. Diagnoses were made by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (6) and the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (7). Participants collected saliva into Salivette tubes (Starstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) over the course of a day at awakening, 8:00 a.m., 12:00 noon, 4:00 p.m., 8:00 p.m., and bedtime. Cortisol was measured by radioimmunoassay as previously described (8). The detection limit was 10 ng/dl, and intra- and interassay variability were 3.9% and 12.0%, respectively.

Data from four subjects could not be used because of substantial deviations from the protocol. Two other subjects were missing one sample; data were interpolated for these points by using the mean of the cortisol value that preceded and followed it. The final study group consisted of 23 Holocaust survivors with PTSD, 19 Holocaust survivors without PTSD, and 25 subjects who had not been exposed to the Holocaust.

The three groups did not differ significantly in time of awakening, time of bedtime, or body mass, but they did differ in age (F=6.10, df=2, 64, p=0.004). The mean age of the PTSD-positive Holocaust survivors was 68.5 years (SD=5.9); the mean age of the PTSD-negative Holocaust survivors was 69.0 (SD=6.3); and the mean age of the nonexposed subjects was 74.1 (SD=6.1). The groups did not differ in gender distribution: there were 10 men and 13 women in the PTSD-positive Holocaust group, nine men and 10 women in the PTSD-negative Holocaust group, and 14 men and 11 women in the nonexposed group. 8:00 a.m. cortisol levels were higher in women (mean=767.8 ng/dl, SD=521.2) than men (mean=505.2 ng/dl, SD=245.0) (F=6.90, df=1, 65, p=0.01). The subjects in the PTSD-positive Holocaust group had significantly higher rates of major depressive disorder (39.1%) than did those in the PTSD-negative Holocaust group (10.5%) (χ2=4.40, df=1, p=0.04); however, major depressive disorder was not significantly associated with cortisol among the Holocaust survivors. Four women were receiving hormone replacement therapy; there was no significant difference in the distribution of hormone replacement therapy in the three groups and no significant effect of this treatment on cortisol values among the women.

Results

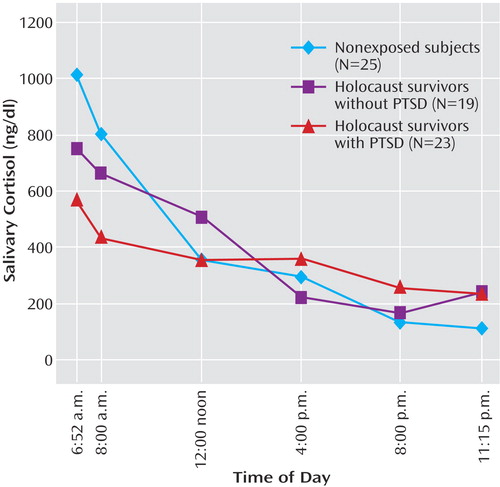

Repeated-measures analysis of covariance of raw cortisol values demonstrated a significant interaction between group and time of day (F=3.01, df=10, 116, p=0.002); none of the covariates (age, gender, major depressive disorder) had a significant effect on the findings. Multivariate analysis of covariance of the six samples demonstrated a main effect of group (Pillai’s F=2.91, df=12, 114, p=0.002); differences were apparent at awakening (F=3.32, df=2, 61, p=0.04), 8:00 a.m. (F=3.89, df=2, 61, p=0.03), and 8:00 p.m. (F=3.34, df=2, 61, p=0.04) (raw data in legend of Figure 1). The differences, according to post hoc pairwise comparisons using Bonferroni adjustment, were attributable to lower cortisol at awakening and 8:00 a.m. and higher cortisol levels at 8:00 p.m. in Holocaust survivors with PTSD than in nonexposed subjects. There were no significant differences between the Holocaust survivors without PTSD and the nonexposed subjects. Because the cortisol values were skewed and kurtotic, the analyses were repeated with log-transformed cortisol levels. A similar pattern emerged: there was a main effect of group (F=3.75, df=12, 114, p<0.0005), with significant post hoc differences at awakening and 8:00 a.m. but not at 8:00 p.m. There was no significant group difference in area under the curve for the raw or log-transformed cortisol data.

Age was not significantly correlated with cortisol at any time point for the whole study group. There was a significant association between age and the raw (r=0.38, N=34, p=0.027) and log-transformed (r=0.34, N=34, p=0.046) 8:00 a.m. cortisol level in women.

Discussion

The data show that Holocaust survivors with PTSD show a flatter circadian rhythm than Jewish adults not exposed to the Holocaust. To our knowledge, this finding provides the first evidence of subtle HPA axis alterations in older people with PTSD. To the extent that these alterations are similar to those described in normal aging, the findings add further evidence to the possibility that there may be an acceleration of the aging process in PTSD. The subjects evaluated in the current study were in the early stages of aging, which may explain why the observed alterations in PTSD were modest and why an overall effect of age in this study group as a whole could not be demonstrated.

It should be noted that the sampling of saliva during waking hours may provide different information than evaluating cortisol levels across the entire diurnal cycle. In a study of 24-hour urine collections, survivors with PTSD were found to have lower cortisol levels (9), but no differences in the area under the curve for cortisol excretion were observed in our study. A previous circadian study in veterans with PTSD conducted over 24 hours, which included time periods that were not fully sampled in our study, found lower cortisol levels that appeared to result from lower nocturnal cortisol release (4).

Group differences in basal cortisol levels have not been as consistently observed in studies of women with PTSD as they have in men (see, e.g., reference 2 for review). Whereas the evaluation of gender differences in PTSD is often confounded by the fact that men and women are exposed to different types of events and at different ages, in Holocaust survivors the same types of traumatic events affected both men and women, allowing for a more direct comparison of the effects of gender. In the present study, women had higher cortisol levels at 8:00 a.m. than men, regardless of PTSD diagnosis, but there were no gender differences related to PTSD. These findings, together with our previous observations, suggest that there are no gender differences related to PTSD in basal cortisol levels in our study group. A relationship between age and cortisol was present only in women, consistent with other observations of gender differences in early aging.

In sum, this study provides preliminary evidence for subtle neuroendocrine alterations in older people with PTSD. As such, the present study offers a rationale for performing a more comprehensive circadian rhythm analysis in older subjects with PTSD and for further assessing the impact of aging on the biology of PTSD.

Received July 7, 2003; revision received Feb. 24, 2004; accepted May 24, 2004. From Mount Sinai School of Medicine and Bronx VA Medical Center. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Yehuda, Psychiatry OOMH, Bronx VA Medical Center, 130 W. Kingsbridge Rd., Bronx, NY 10468; [email protected] (e-mail).

Figure 1. Salivary Cortisol Levels From Awakening to Bedtime in Holocaust Survivors With and Without PTSD and Nonexposed Subjectsa

aData represent the estimated marginal means of cortisol adjusted for age, gender, and presence or absence of major depressive disorder. 6:52 a.m. (SD=0:56) represents the mean wake-time for the study group as a whole, whereas 11:15 p.m. (SD=0:59) represents the mean bedtime for the group. There were no significant group differences in the actual times of the individual groups collected. For the total group, the actual mean collection times were 8:19 a.m. (SD=0:35), 12:14 p.m. (SD=0:45), 4:17 p.m. (SD=0:42), and 8:16 p.m. (SD=0:45). The estimated marginal means for the six time points for each group are as follows: for the Holocaust survivors with PTSD the mean cortisol values from awakening to bedtime were 570.7 ng/dl (SE=115.9), 440.6 ng/dl (SE=87.7), 355.2 ng/dl (SE=96.0), 360.4 ng/dl (SE=84.3), 261.4 ng/dl (SE=34.6), and 235.9 ng/dl (SE=60.6); for the Holocaust survivors without PTSD the corresponding values were 749.8 ng/dl (SE=118.4), 661.8 ng/dl (SE=89.7), 503.6 ng/dl (SE=98.1), 218.6 ng/dl (SE=86.2), 166.5 ng/dl (SE=35.4), and 241.0 ng/dl (SE=62.0); for the nonexposed subjects the values were 1011.8 ng/dl (SE=111.2), 802.7 ng/dl (SE=84.2), 356.6 ng/dl (SE=92.1), 293.0 ng/dl (SE=80.9), 133.0 ng/dl (SE=33.2), and 110.2 ng/dl (SE=58.2).

1. Ferrari E, Arcaini A, Goranti R, Pelanconi L, Cravello L, Fioravanti M, Solerte SB, Magri F: Pineal and pituitary-adrenocortical function in physiological aging and in senile dementia. Exp Gerontol 2000; 35:1239–1250Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Yehuda R: Current status of cortisol findings in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2002; 25:341–368Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Milcu SM, Bogdan C, Nicolau GY, Cristea A: Cortisol circadian rhythm in 70–100-year-old subjects. Endocrinologie 1978; 16:29–39Medline, Google Scholar

4. Yehuda R, Teicher MH, Trestman RL, Levengood RA, Siever LJ: Cortisol regulation in posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression: a chronobiological analysis. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 40:79–88Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Thaller V, Vrkljan M, Hotujac L, Thakore J: The potential role of hypocortisolism in the pathophysiology of PTSD and psoriasis. Coll Antropol 1999; 23:611–619Medline, Google Scholar

6. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

7. Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, Keane TM: The development of a Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. J Trauma Stress 1995; 8:75–90Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Goenjian AK, Yehuda R, Pynoos RS, Steinberg AM, Tashjian M, Yang RK, Najarian LM, Fairbanks LA: Basal cortisol, dexamethasone suppression of cortisol, and MHPG in adolescents after the 1988 earthquake in Armenia. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:929–934Link, Google Scholar

9. Yehuda R, Kahana B, Binder-Brynes K, Southwick SM, Mason JW, Giller EL: Low urinary cortisol excretion in Holocaust survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:982–986Link, Google Scholar