Childhood Trauma and Personality Disorder: Positive Correlation With Adult CSF Corticotropin-Releasing Factor Concentrations

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To test the hypothesis that early life trauma results in adult stress hormone alterations in individuals with personality disorders, the authors examined the relationship between history of childhood adversity and lumbar CSF corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF). METHOD: Participants were 20 otherwise healthy men who met DSM-IV criteria for personality disorders. CSF CRF was obtained by lumbar puncture, and childhood adversity was measured by the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Correlations were obtained between CSF CRF and the total score on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire as well as scores on its four subscales. RESULTS: CSF CRF concentrations were positively correlated with the total score on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Analysis of the subscales revealed that CSF CRF was correlated with emotional neglect. Correlations between CSF CRF level and physical and emotional abuse and with physical neglect were not statistically significant. CONCLUSIONS: Consistent with the hypothesis that the severity of early life stress is correlated with stress hormone abnormalities in adulthood, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire total scores and emotional neglect scores were significantly correlated with CSF CRF levels in individuals with personality disorders.

The stress hormone system has been studied as a mediator of the effects of childhood trauma on psychopathology in preclinical and human studies. The role of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) in affective regulation and the stress response makes it a promising candidate for study in disorders such as borderline personality disorder. To our knowledge, no study to date has investigated the relationship between childhood trauma and CSF CRF concentration in subjects with personality disorders.

This study tested the hypothesis that childhood trauma leads to persistent stress hormone abnormalities in adult subjects with personality disorders, as measured by altered CSF CRF concentration.

Method

The subjects were 20 adult men who met DSM-IV criteria for personality disorders. The men underwent a lumbar puncture to measure CSF CRF and completed the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (1). Subjects were recruited by newspaper advertisement. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating subjects. Physical health was evaluated by medical history, physical examination, laboratory studies, and electrocardiogram. Semistructured interviews (the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia [2] and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV) and best-estimate consensus procedures were used to make axis I and II diagnoses according to DSM-IV criteria. History of childhood trauma was assessed by the self-administered Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Other behavioral data examined included global functioning (Global Assessment of Functioning Scale [GAF] [DSM-IV, p. 32) and general personality measures (the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire [3] and the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire [4]).

Five subjects had cluster A personality disorders (five paranoid and one schizoid), five subjects had cluster B personality disorders (two antisocial, one histrionic, and two narcissistic), five subjects had a cluster C personality disorder (all five obsessive-compulsive), and nine subjects had a diagnosis of personality disorder not otherwise specified. (Subjects could have more than one personality disorder.)

Five subjects had a history of major depressive disorder, currently in remission. One had a history of dysthymia, and one had current substance abuse. No subjects had a history of bipolar disorder, psychosis, or anxiety disorder. Two subjects had a history of attention deficit disorder, and two had a history of intermittent explosive disorder.

This study used the original 70-item self-report Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (1), which provides a retrospective assessment of traumatic childhood experiences. Principal components analysis of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire yields four main factors: physical and emotional abuse, emotional neglect, sexual abuse, and physical neglect (5).

Five of the 20 subjects had a documented history of past, but not current, treatment with psychotropic agents. All subjects were instructed to remain drug free for 2 weeks and to follow a low monoamine diet for at least 3 days before the study.

Subjects reported to the laboratory at 9:00 p.m. the evening before lumbar puncture. At 9:00 a.m. the next day, subjects completed a visual analogue scale rating subjective mood state. At 10:00 a.m., lumbar punctures were performed under sterile technique. A total of 20 cc of CSF was withdrawn in six aliquots. CSF from the third aliquot was assayed for CRF. All CSF samples were frozen immediately at –70°C until assay. Assays of CRF and ACTH were by radioimmunoassay using reagents provided by IgG Corp. (Nashville, Tenn.). CSF CRF inter- and intraassay coefficients of variability were 11.9% and 7.2%, respectively. ACTH inter- and intraassay coefficients of variability were 11.0% and 7.0%, respectively (6).

The primary methods of data analysis relied on Pearson product-moment correlations and t tests. All CSF variables were normally distributed. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire total scores were normally distributed, as were the scores on Childhood Trauma Questionnaire subscales, with the exception of sexual abuse. Median split analysis was done to estimate the magnitude of the difference in the study group between subjects reporting categorically high versus low amounts of childhood trauma by Childhood Trauma Questionnaire total score.

Results

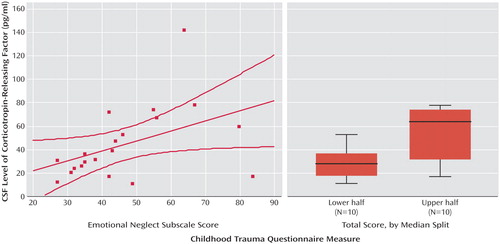

CSF CRF levels were significantly, positively correlated with Childhood Trauma Questionnaire total scores (r=0.48, N=20, p<0.04) (Figure 1). Median split analysis revealed the same relationship: CSF CRF levels of subjects with scores above the median Childhood Trauma Questionnaire total score were significantly higher than those of subjects with scores below the median total score (mean=60.5, SD=36.3, versus mean=28.5, SD=14.2) (t=2.60, df=18, p<0.03). Subsequent analysis of the four Childhood Trauma Questionnaire subscales revealed a statistically significant positive correlation between CSF CRF levels and emotional neglect (r=0.45, N=20, p<0.05). Correlations between CSF CRF concentration with physical and emotional abuse and physical neglect were smaller in magnitude and not significant (r=0.33, N=20, p=0.15, and r=0.34, N=20, p<0.14, respectively). The relationship between CSF CRF and sexual abuse could not be examined because of the restriction of range in scores for this Childhood Trauma Questionnaire subscale. Age, race, socioeconomic status, and GAF were not correlated with CSF CRF levels or with Childhood Trauma Questionnaire total score.

Despite the fact that the CSF CRF level correlated significantly with CSF ACTH level (r=0.46, N=20, p<0.05), no correlation was noted between CSF ACTH and the total Childhood Trauma Questionnaire score. CSF CRF levels were not correlated with any of the personality variables measured (Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire and Eysenck Personality Questionnaire) and were not correlated with subjective mood states as measured by visual analogue scale.

Discussion

The results of this study reveal a direct correlation between CSF CRF levels and history of childhood trauma in men with personality disorders. The results suggest that of all forms of childhood trauma assessed, childhood emotional neglect has the strongest relationship with CRF levels in personality disorders. Most human studies so far have focused on other forms of trauma, such as sexual and physical abuse. However, the type of child trauma measured by the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire emotional neglect subscale is analogous to the disruptions in maternal care administered in rodent handling and separation paradigms (7) and primate variable foraging paradigms (8). These studies have found evidence that early life stress leads to greater hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis function by means of less negative feedback at the level of the hippocampus and greater CRF concentration (7, 9).

CSF CRF levels have recently been found to be positively associated with perceived early life stress in depressed and nondepressed subjects (10). Human studies have demonstrated abnormal HPA axis function in association with history of childhood abuse in the form of enhanced ACTH hormone response to exogenous CRF (11).

Given the presence of CRF receptors in areas of the brain associated with emotional and cognitive processing such as the amygdala and neocortex, CRF may play a role in personality psychopathology. Preliminary studies have found relationships between HPA axis abnormalities and dimensional aspects of personality psychopathology such as elevated arginine vasopressin levels in impulsive-aggressive subjects (12).

The limitations of our study include a small number of subjects, inadequate power to explore the relationship between CRF and dimensional measures of temperament, the inclusion of only male subjects, retrospective assessment of history of childhood trauma, and the stressful nature of the lumbar puncture. Further work in this area should clarify the links between childhood trauma, CNS neurochemistry, and personality psychopathology.

Received June 5, 2003; revision received March 16, 2004; accepted May 26, 2004. From the Clinical Neuroscience and Psychopharmacology Research Unit, Department of Psychiatry, University of Chicago; Cincinnati VA Medical Center, Psychiatry Service; Department of Psychiatry, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine; University of Cincinnati Neurosciences Program; and Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University, New York. Address correspondence and reprint request to Dr. Lee, Clinical Neuroscience and Psychopharmacology Research Unit, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Chicago, 5841 S. Maryland Ave., Chicago, IL 60637; [email protected] (e-mail).

Figure 1. History of Childhood Trauma and CSF Corticotropin-Releasing Factor Concentrations in 20 Men With Personality Disordersa

aOn the left, CSF corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) concentrations were directly correlated with the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire emotional neglect subscale scores (r=0.49, N=20, p<0.03). The box plot on the right diagrams CSF CRF concentrations in subjects divided by median split of Childhood Trauma Questionnaire total scores. Mean CSF CRF levels were significantly higher in subjects with higher total scores (mean=60.5, SD=36.3) than in those with lower total scores (mean=28.5, SD=14.2) (t=2.60, df=18, p<0.03).

1. Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, Sapareto E, Ruggiero J: Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1132–1136Link, Google Scholar

2. Endicott J, Spitzer RL: A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:837–844Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Cloninger CR: A systematic method for clinical description and classification of personality variants. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:573–588Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG: Eysenck Personality Questionnaire Manual. San Diego, Educational and Industrial Testing Service, 1975Google Scholar

5. Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L: Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:340–346Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Kasckow JW, Hagan M, Mulchahey JJ, Baker DG, Ekhator NN, Strawn JR, Nicholson W, Orth DN, Loosen PT, Geracioti TD: The effect of feeding on cerebrospinal fluid corticotropin-releasing hormone levels in humans. Brain Res 2001; 904:218–224Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Meaney MJ, Diorio J, Francis D, Widdowson J, LaPlante P, Caldji C, Sharma S, Seckl JR, Plotsky PM: Early environmental regulation of forebrain glucocorticoid receptor gene expression: implications for adrenocortical responses to stress. Dev Neurosci 1996; 18:49–72Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Coplan JD, Andrews MW, Rosenblum LA, Owens MJ, Friedman S, Gorman JM, Nemeroff CB: Persistent elevations of cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of corticotropin releasing factor in adult nonhuman primates exposed to early-life stressors: implications for the pathophysiology of mood and anxiety disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996; 93:1619–1623Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ: Early, postnatal experience alters hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) mRNA, median eminence CRF content and stress-induced release in adult rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 1993; 18:195–200Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Carpenter LL, Tyrka AR, McDougle CJ, Malison RT, Owens MJ, Nemeroff CB, Price LH: Cerebrospinal fluid corticotropin-releasing factor and perceived early-life stress in depressed patients and healthy control subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004; 29:777–784Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Heim C, Newport DJ, Bonsall R, Miller AH, Nemeroff CB: Altered pituitary-adrenal axis responses to provocative challenge tests in adult survivors of childhood abuse. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:575–581Link, Google Scholar

12. Coccaro EF, Kavoussi RJ, Hauger RL, Cooper TB, Ferris CF: Cerebrospinal fluid vasopressin levels: correlates with aggression and serotonin function in personality-disordered subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:708–714Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar