The Effects of Clozapine and Risperidone on Spatial Working Memory in Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this investigation was to evaluate the effects of clozapine and risperidone on spatial working memory in patients with schizophrenia. METHOD: Spatial working memory performance was evaluated at baseline and after 17 and 29 weeks in 97 patients with schizophrenia participating in a multisite trial. RESULTS: Compared with baseline performance while receiving conventional antipsychotic medication, risperidone improved, and clozapine worsened, spatial working memory performance. CONCLUSIONS: The differential effects of these medications on spatial working memory may be due to the anticholinergic effects of clozapine and prefrontal dopamine-enhancing effects of risperidone.

Spatial working memory is a neuropsychological function of special interest in schizophrenia. First, nonhuman primate and human studies have demonstrated that spatial working memory processes rely on intact functioning of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (1, 2), an area associated with core deficits in schizophrenia. Second, studies that have evaluated spatial working memory using a variety of spatial delayed-response paradigms have demonstrated impairments in patients with schizophrenia (3, 4). Third, persons at risk for the illness demonstrate impairments in spatial working memory, including first-degree biological relatives (5) and high-risk adolescents who later develop schizophrenia (6), indicating that spatial working memory may be an endophenotype for schizophrenia. Fourth, spatial working memory deficits are associated with impaired community functioning, including work (7). Thus, spatial working memory taps neural processes that are of fundamental interest in schizophrenia, and impairments may indicate risk for illness and impaired community function.

Spatial working memory performance is also of interest in the evaluation of medications because it is altered by drugs commonly used in the treatment of schizophrenia. For example, in a 4-week, double-blind, randomized trial, risperidone improved, while haloperidol worsened, spatial working memory performance, an effect largely due to coadministration of benztropine with haloperidol (8). Because clozapine exhibits potent antimuscarinic activity in vitro at a magnitude similar to that seen with benztropine (9, 10), it may exert a deleterious effect on spatial working memory. Such an effect is suggested by impairment in visual memory (11, 12) and verbal working memory (13) during clozapine treatment. A more recent controlled trial comparing clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and haloperidol (14) indicated that verbal working memory and visual memory were unchanged from baseline in patients receiving clozapine and risperidone. Spatial working memory was not evaluated.

In addition, nonhuman primate studies have demonstrated that spatial working memory is impaired by D1 antagonists and improved by D1 agonists (15), indicating that spatial working memory is modulated, in part, by prefrontal dopaminergic processes. Thus, beneficial effects of risperidone compared with haloperidol on working memory (16) may be due to both its relative lack of anticholinergic properties (8, 17) as well as its ability to enhance dopamine activity in the prefrontal cortex (17).

The current study evaluated the effects of clozapine and risperidone on performance of a computerized assessment of spatial working memory in patients with moderately refractory schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. It was hypothesized that relative to clozapine, risperidone would improve spatial working memory.

Method

This study was part of a larger 6-month, multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled trial comparing clozapine (target dose: 500 mg/day) and risperidone (target dose: 6 mg/day) in patients with moderately treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Clinical and adverse event data have been reported elsewhere (unpublished study of N.R. Schooler et al.). Subjects treated with clozapine were less likely to discontinue treatment for lack of efficacy (15%) than those treated with risperidone (38%) and showed more improvement globally and in asociality. Other reasons for discontinuation included withdrawal of consent and treatment-related side effects. However, the proportion of subjects meeting an a priori criterion of psychosis symptom improvement (20% improvement on at least one of four psychotic symptoms) did not significantly differ between the two groups (risperidone: 57%; clozapine: 71%). A previous report of this study indicated no medication effects on social competence or problem solving (18). All subjects provided informed written consent for their participation.

Subjects

Study participants met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder as determined by a diagnostic checklist based on a structured interview. Subjects’ illness had shown evidence of treatment resistance, defined as at least one trial of a conventional antipsychotic at a dose equivalent to 600 mg/day of chlorpromazine, a second trial of a different conventional antipsychotic at a dose equivalent to 250–500 mg/day of chlorpromazine, and at least a moderate severity score on one of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (19) psychotic symptom subscale items or on one of the Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (20) global subscales. Last, subjects were 18–60 years of age and were living in the community or judged potentially dischargeable from the hospital. Exclusion criteria were diagnosis of neuroleptic malignant syndrome with recurrence upon rechallenge, history of CNS pathology, pregnancy, or mental retardation that precluded understanding study participation or assessment procedures.

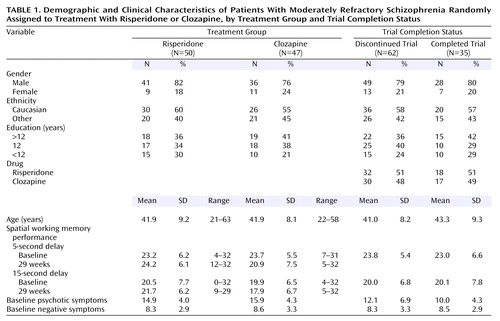

Of the subjects recruited for the parent study (N=107), 97 completed baseline spatial working memory tests. Fifty subjects were randomly assigned to treatment with risperidone, and 47 received clozapine. Demographic variables (age, gender, education, ethnicity) by drug group are presented in Table 1.

Assessments

The BPRS was used to assess clinical symptoms. Composite scores of the psychotic symptom subscale (hallucinations, delusions, suspiciousness, and conceptual disorganization) and the negative symptoms anergia subscale (emotional withdrawal, blunted affect, motor retardation) were used in statistical analyses.

Spatial working memory was measured using a computerized delayed response test (8) imposing one of two delays (5 or 15 seconds) between stimulus presentation (a black circle occurring in one of eight possible locations) and response (subjects pointed to the location of the target stimulus at the end of the delay). Thirty-two trials of each delay condition were presented. The dependent measure was the number of correctly identified targets at each delay. The test was approximately 20 minutes in duration. Practice trials, which were not included in the total score, consisted of 16 target presentations. For the initial eight practice trials, the target remained on the screen for 5 seconds and overlapped with the eight target choice displays. Because there was no delay between target presentation and response, accurate responding did not require memory, but required the ability to perceive test stimuli and point to the target. The next eight practice trials were identical to the 5-second delay trials and were also administered to ensure that subjects understood test procedures.

Procedure

Clinical and cognitive assessments were performed at baseline and 17 and 29 weeks after initiation of clozapine or risperidone treatment. Clozapine was initiated at 12.5 mg/day and gradually titrated to 500 mg/day by day 28. Risperidone was initiated at 1 mg/day and gradually titrated to 6 mg/day by day 15. Simultaneous with beginning clozapine or risperidone, baseline antipsychotic medication was gradually decreased. Treatment was continued for up to 29 weeks with maximum dosage of 800 mg/day of clozapine or 16 mg/day of risperidone after 5 weeks.

Statistical Analyses

Changes in spatial working memory performance were examined by computing mixed effects regression models (21) with drug (clozapine or risperidone) as the independent variable, baseline spatial working memory performance as a covariate, and spatial working memory performance at 17 weeks and 29 weeks as the repeated dependent variables. The main effect for drug in these analyses is a test of whether the two medication groups differed in spatial working memory performance after baseline performance was controlled. Analyses were conducted by using SAS PROC MIXED (22). Parallel analyses were performed for the 5- and 15-second delays of the spatial working memory test. In order to evaluate whether associations between symptoms and cognitive functioning accounted for the observed drug effects, BPRS psychotic symptom and anergia subscale scores at the two assessment points were included as changing covariates in two subsequent mixed effects models with the same independent and dependent variables.

Results

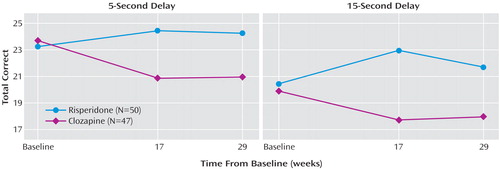

Subjects receiving clozapine and risperidone did not differ in terms of any background characteristic or on measures of baseline psychopathology and spatial working memory, as determined by t tests and chi-square analyses (Table 1). A total of 64 subjects (65%) completed the 17-week assessment, 46 subjects (47%) completed the 29-week assessment, and 35 subjects (36%) completed all three assessments. Comparisons between study completers and noncompleters on background characteristics, symptoms, and cognitive performance indicated no significant differences (Table 1). Seven subjects with baseline values only were excluded from the analysis. The mixed effects regression models indicated a significant main effect for drug for spatial working memory at the 5-second delay (F=6.60, df=1, 61, p<0.02) and the 15-second delay (F=13.52, df=1, 61, p=0.0005). The addition of the covariates of psychotic symptoms and anergia to the models had negligible effects on the main effect for drug (5-second delay: F=6.76, df=1, 58, p<0.02; 15-second delay: F=13.76, df=1, 58, p=0.0005). None of the drug-by-time interactions was statistically significant (p>0.10). As can be seen in Figure 1, the main effects for drug reflect a pattern in which the spatial working memory performance of patients receiving risperidone improved from baseline at both the 5- and 15-second delay conditions, whereas the performance of patients receiving clozapine worsened.

Discussion

In this 29-week, double-blind evaluation of the effects of clozapine versus risperidone on spatial working memory, the performance of patients receiving risperidone improved and that of patients receiving clozapine worsened. The differential effects of clozapine and risperidone on spatial working memory performance were evident at 17 weeks of treatment and consistent through 29 weeks. The effects of clozapine and risperidone were similar for both the 5- and the 15-second delay conditions, and were actually stronger when symptoms were statistically controlled.

The differential effect of risperidone and clozapine on spatial working memory performance may be due to differences in the receptor affinities of the two drugs. Specifically, clozapine has substantial anticholinergic properties that risperidone lacks (17). That the anticholinergic properties of clozapine account for the worse performance on the spatial working memory task is supported by substantial evidence that anticholinergic drugs impair this function (23) and by evidence that clozapine impaired performance on a visual memory task similar to the spatial working memory task (11). The improvement in spatial working memory performance associated with risperidone treatment may be due to its ability to enhance dopaminergic turnover in the frontal cortex in the absence of potent anticholinergic effects, consistent with the effects of experimental dopaminergic agonists on spatial working memory performance in nonhuman primates, as stated in the introduction.

The findings in the current study are consistent with those from a previous double-blind comparison of haloperidol and risperidone that used the same spatial working memory paradigm (8). In that study, haloperidol worsened performance compared with risperidone, an effect associated with benztropine use in patients receiving haloperidol. Risperidone treatment was associated with improved performance relative to haloperidol and to baseline performance, similar to results reported here. Taken together, these two studies support the conclusion that risperidone improves spatial working memory, perhaps by potentiating prefrontal dopaminergic activity.

There was significant attrition in the current study, with 97 subjects participating in the baseline assessment, 62 (64%) at the 17-week assessment, and 35 (36%) at the 29-week assessment. However, there were no differences between patients who dropped out and study completers in terms of any background characteristics, baseline symptoms, or spatial working memory performance. Furthermore, there were no differences in the dropout rate between the clozapine and risperidone groups, suggesting that two drugs were comparably tolerable.

Treatment-related changes in spatial working memory performance were unlikely to be related to differential drug impact on stimuli perception or motor response because practice trials with no delay between stimuli and response were conducted before testing to ensure that subjects were able to 1) perceive test stimuli, which were relatively large (1-inch diameter circles), and 2) carry out the response (pointing to a target stimulus) with 90% accuracy. Risperidone and clozapine may have differential impact on aspects of attention necessary for task performance, a topic of interest for future studies.

In sum, clozapine and risperidone demonstrated differential effects on spatial working memory, with clozapine impairing performance and risperidone improving it. These effects appear to be due mainly to the antimuscarinic blockade produced by clozapine and the enhanced prefrontal dopaminergic transmission associated with risperidone.

|

Received April 14, 2004; revision received July 17, 2004; accepted July 23, 2004. From the Mount Sinai School of Medicine; the UC Davis Department of Psychiatry and Psychology, Sacramento, Calif.; Pfizer Pharmaceutical, Inc., New York; the UCLA Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, Los Angeles; the Department of Veterans Affairs VISN 22 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center, Los Angeles; the New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center, Dartmouth Medical School, Lebanon, N.H.; the Department of Psychiatry, The Zucker Hillside Hospital, Glen Oaks, N.Y., and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, N.Y. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. McGurk, Department of Psychiatry, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, One Gustave L. Levy Pl., New York, NY 10029; [email protected] (e-mail).

Figure 1. Spatial Working Memory Performance Over Time in Patients With Moderately Refractory Schizophrenia Randomly Assigned to Treatment With Risperidone or Clozapine

1. Wilson FA, O’Scalaidhe SP, Goldman-Rakic PS: Dissociation of object and spatial processing domains in primate prefrontal cortex. Science 1993; 260:1955–1958Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Carter CS, Perlstein W, Ganguli R, Brar J, Mintun M, Cohen JD: Functional hypofrontality and working memory dysfunction in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1285–1287Link, Google Scholar

3. Park S, Holzman P: Schizophrenics show spatial working memory deficits. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:975–982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Keefe RSE, Lees Roitman SE, Harvey PD, Blum CS, DuPre RL, Prieto DM, Davidson M, Davis KL: A pen-and-paper human analogue of a monkey prefrontal cortex activation task: spatial working memory in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1995; 17:25–33Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Park S, Holzman PS, Goldman-Rakic PS: Spatial working memory deficits in the relatives of schizophrenic patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:821–828Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Glahn DC, Therman S, Manninen M, Huttunen M, Kaprio J, Lonnqvist J, Cannon TD: Spatial working memory as an endophenotype for schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 53:624–626Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. McGurk SR, Meltzer HY: The role of cognition in vocational functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2000; 45:175–184Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. McGurk SR, Green MF, Wirshing WC, Ames D, Marshall BD, Kern R, Marder SM: Antipsychotic and anticholinergic effects on two types of spatial memory in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2004; 68:225–233Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Snyder S, Greenberg D, Yamamura HI: Antischizophrenic drugs and brain cholinergic receptors: affinity for muscarinic sites predicts extrapyramidal effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1974; 31:58–71Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Bolden C, Cusack B, Richelson E: Antagonism by antimuscarinics and neuroleptic compounds at the five cloned human muscarinic cholinergic receptors cloned on hamster ovary cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1992; 260:576–580Medline, Google Scholar

11. Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR: The effects of clozapine on neurocognition: an overview. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55(9, suppl B):88–90Google Scholar

12. Hoff AL, Faustman WO, Wieneke M, Espinoza S, Costa M, Wolkowitz O, Csernansky JG: The effects of clozapine on symptom reduction, neurocognitive function, and clinical management in treatment-refractory state hospital schizophrenic inpatients. Neuropsychopharmacology 1996; 15:361–369Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Hagger C, Buckley P, Kenny JT, Friedman L, Ubogy D, Meltzer HY: Improvement in cognitive functions and psychiatric symptoms in treatment-refractory schizophrenic patients receiving clozapine. Biol Psychiatry 1993; 34:702–712Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Bilder RM, Goldman RS, Volavka J, Czobor P, Hoptman M, Sheitman B, Lindenmayer J-P, Citrome L, McEvoy J, Kunz M, Chakos M, Cooper TB, Horowitz TL, Lieberman JA: Neurocognitive effects of clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in patients with chronic schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1018–1028Link, Google Scholar

15. Castner SA, Williams GV, Goldman-Rakic PS: Reversal of antipsychotic-induced working memory deficits by short-term dopamine D1 receptor stimulation. Science 2000; 287:2020–2022Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Green MF, Marshall BD Jr, Wirshing WC, Ames D, Marder SR, McGurk S, Kern RS, Mintz J: Does risperidone improve verbal working memory in treatment-resistant schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:799–804Link, Google Scholar

17. Schotte A, Janssen PFM, Gommeren W, Luyten W, Van Grompel P, Lesage AS, De Loore K, Leysen JE: Risperidone compared with new and reference antipsychotic drugs: in vitro and in vivo receptor binding. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996; 124:57–73Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Bellack AS, Schooler NR, Marder SR, Kane JM, Brown CH, Yang Y: Do clozapine and risperidone affect social competence and problem solving? Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:364–367Link, Google Scholar

19. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep 1962; 10:799–812Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Andreasen NC: Modified Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1984Google Scholar

21. Laird NM, Ware JH: Random effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics 1982; 38:963–974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. SAS System for Mixed Models. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1996Google Scholar

23. Bartus RT, Johnson HR: Short-term memory in the rhesus monkey: disruption from the anti-cholinergic scopolamine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1976; 5:39–46Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar