Psychosocial Treatment for First-Episode Psychosis: A Research Update

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This article reviews research on psychosocial treatment for first-episode psychosis. METHOD: PsycINFO and MEDLINE were systematically searched for studies that evaluated psychosocial interventions for first-episode psychosis. RESULTS: Comprehensive (i.e., multielement) treatment approaches show promise in reducing symptoms and hospital readmissions, as well as improving functional outcomes, although few rigorously controlled trials have been conducted. Individual cognitive behavior therapy has shown modest efficacy in reducing symptoms, assisting individuals in adjusting to their illness, and improving subjective quality of life, but it has shown minimal efficacy in reducing relapse. Some controlled research supports the benefits of family interventions, while less controlled research has evaluated group interventions. CONCLUSIONS: Adjunctive psychosocial interventions early in psychosis may be beneficial across a variety of domains and can assist with symptomatic and functional recovery. More randomized, controlled trials are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions, particularly for multielement, group, and family treatments.

Psychotic disorders, particularly schizophrenia, are the most disabling of all mental illnesses. In fact, schizophrenia is included among the world’s top 10 causes of disability-adjusted life-years (1). The majority of individuals with schizophrenia have a poor long-term outcome (2–4), which results in great personal suffering and societal cost. The largest expenditure for mental health in the United States is for schizophrenia (5), with an annual cost of $32.5 billion (6–8). Most of this cost can be attributed to repeated hospitalizations following relapse (9).

In an effort to improve the long-term outcome for individuals with schizophrenia, research has focused on early identification and intervention for psychosis. This approach to secondary prevention has been bolstered by findings that the sooner antipsychotic treatment is initiated after the emergence of psychosis, the better the clinical response (for example, see reference 10; see references 11 and 12 for reviews and references 13–16 for exceptions). In addition, most clinical and psychosocial deterioration in schizophrenia occurs within the first 5 years of the onset of the illness (11), suggesting that this is a critical period for treatment initiation (17, 18). Thus, pharmacological and psychosocial treatment delivered during this critical period has been hypothesized to have a stronger impact than comparable treatment provided later in the illness (17). Finally, there is a growing risk of treatment-resistant symptoms with each subsequent relapse (19–24). This is consistent with findings that show progressive loss of brain gray matter associated with recurrent episodes, suggesting that each relapse may reduce the individual’s capacity to respond to subsequent treatment (25, 26). Early intervention may therefore reduce the risk of relapse and long-term disability associated with chronic schizophrenia (27–29).

Pharmacological Treatment of First-Episode Psychosis

Most individuals with first-episode psychosis are responsive to antipsychotic medication (30). Remission of psychotic symptoms occurs in 50% of individuals with first-episode psychosis within the first 3 months after initiation of treatment with antipsychotic medication (24, 31, 32), 75% within the first 6 months (32), and up to 80% at 1 year (31, 33–35).

The beneficial effects of antipsychotic medication on first-episode psychosis are tempered by the following issues: 1) individuals with first-episode psychosis are particularly sensitive to the side effects of antipsychotics, such as weight gain (36, 37), 2) medication adherence is variable, with 6–12-month adherence rates in the 33%–50% range (38, 39), 3) up to 20% of individuals with first-episode psychosis show persistent psychotic symptoms (40), and 4) over 50% of individuals with first-episode psychosis report significant depression and/or anxiety secondary to the traumatic nature of psychosis (41–43).

In addition, despite initial symptom reduction, there is poor functional recovery following a first psychotic episode. Tohen et al. (32) found that although approximately 75% of individuals with first-episode psychosis showed symptom remission at 6 months, most (79.8%) failed to show functional recovery during the same time period (see also reference 35). Individuals with first-episode psychosis tend to have impairments in general social functioning (44, 45), quality of life (46, 47), and occupational functioning (48) despite clinical recovery. These functional impairments are present up to 5 years after illness onset even when optimal pharmacological treatment is provided (49).

Psychosocial Interventions for First-Episode Psychosis

Clearly, pharmacotherapy alone is not sufficient to prevent relapses or assure functional recovery from acute psychosis. Thus, there is a growing interest in psychosocial interventions as a means of facilitating recovery from an initial episode of psychosis and reducing the long-term disability associated with schizophrenia (50). Work in this area is still in its infancy, however. Treatment guidelines for first-episode psychosis, which include therapeutic engagement, targeting psychological and social adjustment, developing an active relapse prevention plan, and identifying barriers to treatment (42, 51, 52), are based on clinical experience and not controlled research evaluating standardized psychosocial programs. There is a need for updated guidelines, informed by a rigorous review of available research.

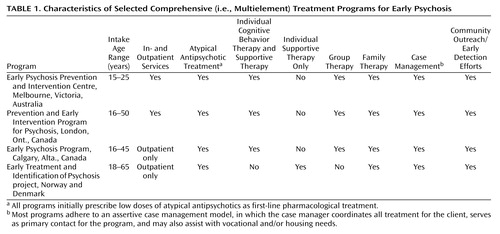

According to Edwards and colleagues (53–55), the literature on psychosocial interventions for first-episode psychosis can be conceptualized as constituting two broad categories: 1) studies evaluating comprehensive (i.e., multielement) interventions, which typically include community outreach/early detection efforts, in- and outpatient individual, group, and/or family therapy, and case management, in addition to pharmacological treatment (see Table 1 for examples), and 2) studies evaluating specific (i.e., single-element) psychosocial interventions (e.g., individual cognitive behavior therapy). In this article we review the extant literature on psychosocial interventions for early psychosis in light of these two categories.

Search Strategy

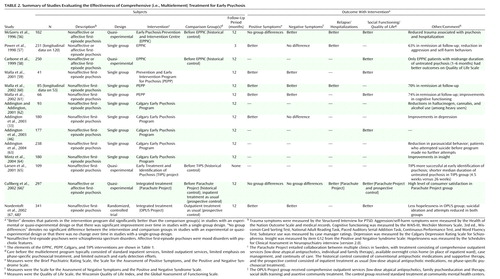

A comprehensive search of the PsycINFO and MEDLINE databases (January 1983 to October 2004) was conducted by using the following terms: 1) “first-episode schizophrenia” and “psychosocial treatment” (or “therapy or treatment”), 2) “first-episode psychosis” and “psychosocial treatment” (or “therapy or treatment”), and 3) “early psychosis” and “psychosocial treatment” (or “therapy or treatment”). The results were evaluated for relevance, and only the studies evaluating psychosocial interventions for first-episode psychosis were selected for review. Specifically, we selected papers that quantitatively evaluated multielement interventions, individual cognitive behavior and supportive therapy approaches, and group and family interventions. The designs of the studies reported in the selected articles included experimental/randomized-controlled (i.e., comparing outcomes in randomized groups), quasi-experimental (i.e., comparing outcomes in nonrandomized groups), and single-group (i.e., evaluating change over time in one group of individuals receiving treatment). Studies that compared subgroups of patients within a particular intervention or program (e.g., patients with short durations of untreated psychosis versus patients with long durations of untreated psychosis) were excluded. Finally, to ensure that our search was as comprehensive and current as possible, we also conducted independent searches for recent publications by leading psychosocial researchers in the field of early psychosis (e.g., Addington, Birchwood, Edwards, Jackson, Lewis, Linszen, Malla, McGorry, Morrison, Tarrier). The findings of all of the selected studies are summarized in Table 2 (multielement studies) and Table 3 (single-element studies).

Multielement Interventions

Multielement programs offer a comprehensive array of specialized in- and outpatient services designed for individuals experiencing first-episode psychosis, and they emphasize both symptomatic and functional recovery. Further, many of the issues that are particularly problematic among young individuals experiencing psychosis (e.g., substance abuse, suicidality, engagement with the mental health system) are addressed through a variety of targeted therapeutic approaches. Table 1 provides general information about several multielement programs and their respective components (for a full description of these and additional programs, see reference 55).

The Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre in Australia is an exemplar of multielement care for first-episode psychosis and consists of a mobile assessment and treatment team; a 16-bed inpatient unit; in- and outpatient case management (including housing and vocational assistance); individual, group, and family therapy; pharmacological management (emphasizing low doses of atypical antipsychotic medication as first-line treatment); and specialized treatment for individuals with persistent psychotic symptoms. The Prevention and Early Intervention Program for Psychosis and the Calgary Early Psychosis Program are additional examples of established early intervention centers (55). There have also been several large-scale efforts to evaluate the effectiveness of multielement treatment approaches for early psychosis delivered in the context of existing systems of care. For example, the Early Treatment and Identification of Psychosis project is a prospective, longitudinal 5-year study investigating whether early detection and treatment of psychosis can lead to better long-term outcomes (85). A quasi-experimental design is comparing outcomes among individuals with nonaffective first-episode psychosis at three sites: 1) Rogaland, Norway, 2) Oslo, Norway, and 3) Ros-kilde, Denmark. All three sites offer multielement care, including individual supportive therapy, family work, case management, and pharmacological treatment; however, only the Rogaland site includes specialized early detection and community outreach efforts. Additional efforts to evaluate multielement models of care include the Parachute Project in Sweden, a collaboration among multiple psychiatric clinics to adapt and implement comprehensive first-episode services (i.e., low-dose atypical antipsychotic treatment, case management, individual and family therapy, and access to overnight crisis homes as an alternative to hospitalization) (66), and the OPUS Project in Denmark, which evaluated the effectiveness of comprehensive, integrated care across a variety of treatment modalities (i.e., low-dose atypical antipsychotic treatment, assertive community treatment, family psychoeducation, and social skills training) (67, 68). Indeed, the multielement model of care for early psychosis has been in existence for only a little over a decade but has already garnered significant research support across a variety of programs.

Examination of Table 2 reveals that only one randomized, controlled trial of a multielement intervention has been conducted thus far (67, 68). While additional programs are currently being evaluated in randomized, controlled designs, e.g., at the Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre (55), the majority of published research in this area has utilized quasi-experimental and single-group designs to evaluate program effectiveness. Thus, the findings should be viewed with caution. Nevertheless, data emerging from these interventions have been encouraging.

A review of Table 2 indicates that multielement interventions for early psychosis have been associated with symptom reduction and/or remission (33, 56, 57, 59–61, 68), improved quality of life and social functioning (46, 56, 58, 59, 61, 68), improved cognitive functioning (61), reduced duration of untreated psychosis (65), low rates of inpatient admissions (56, 60, 66), improved insight (64), high level of satisfaction with treatment (66), less time spent in the hospital (56, 66), decreased substance abuse (62), fewer self-harm behaviors (57, 63, 67), and reduced trauma secondary to psychosis and hospitalization (56). It should be noted that the foregoing results primarily refer to 1-year outcomes; longer-term benefits conferred by multielement programs have not been widely reported. Finally, a recent study suggests that these comprehensive and specialized first-episode services are likely to yield superior outcomes (e.g., shorter duration of untreated psychosis, fewer inpatient admissions, less time in the hospital) when compared with generic mental health services (86).

Single-Element Interventions

Single-element studies have evaluated the effectiveness of specific psychosocial interventions, rather than assessing the effects of a comprehensive, multielement intervention as a whole. That is, these studies sought to measure the relative utility of various adjunctive psychosocial interventions in the treatment of early psychosis. These interventions were offered in addition to pharmacological treatment and, in some cases, other services as well (e.g., case management). Examination of Table 3 reveals that several randomized, controlled trials have been conducted with respect to individual cognitive behavior therapy in early psychosis, but less controlled research has evaluated group and family interventions. Findings from many of these studies have been promising, and the results are discussed in more detail in the following sections.

Individual Therapy

Individual therapy for first-episode psychosis has been examined both for facilitating recovery from acute psychosis and for improving longer-term outcome following remission of acute psychosis. With respect to the former, the Study of Cognitive Reality Alignment Therapy in Early Schizophrenia was a large, multisite randomized, controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy for recent-onset acute psychosis. On the basis of a pilot study by Haddock et al. (69), Lewis and colleagues (70) randomly assigned 309 individuals who had either a first (83%) or second psychiatric admission for psychosis to 5 weeks of cognitive behavior therapy and routine care, supportive counseling and routine care, or routine care alone. While all groups improved over the course of treatment, the group receiving cognitive behavior therapy improved nonsignificantly faster. Further, auditory hallucinations improved significantly faster in that group than in the group receiving supportive counseling. There were no significant group differences, however, in symptoms at the end of treatment. At 18-month follow-up, Tarrier and colleagues (71) found that both cognitive behavior therapy and supportive counseling were significantly better than routine care in reducing symptoms. Further, auditory hallucinations responded better to cognitive behavior therapy than to supportive counseling. However, there were no group differences in relapse rates, with high overall rates of relapse across the total study group. Tarrier et al. hypothesized that the short duration of treatment, a failure of treatment effects to generalize outside the hospital, potential exposure to environmental stressors after discharge, and the tendency for relapse to accumulate over time in first-episode psychosis may explain the lack of an impact on relapse conferred by cognitive behavior therapy or supportive counseling. Nevertheless, these results suggest that individual therapy (i.e., cognitive behavior therapy or supportive counseling) may have beneficial long-term effects on symptoms in early psychosis.

Promising results have also been reported with respect to cognitive behavior therapy conducted during the period of recovery following reduction of acute psychotic symptoms. Jackson and colleagues (72) conducted a prospective study of cognitively oriented psychotherapy for early psychosis with 80 individuals in the Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre program who were experiencing nonaffective or affective first-episode psychosis. Cognitively oriented psychotherapy for early psychosis promoted adjustment to the illness, helped individuals resume developmental tasks, and focused on overall recovery, in addition to targeting secondary morbidity (i.e., depression, anxiety). Forty-four individuals received cognitively oriented psychotherapy as part of their outpatient care, 21 refused but received all of the center’s other services, and 15 individuals received inpatient care only with no additional services following discharge (they were designated the control group). At the end of treatment, the patients receiving cognitively oriented psychotherapy performed significantly better than the control group on measures of insight and attitudes toward treatment, adaptation to illness, quality of life, and negative symptoms, but they significantly outperformed the refusal group only with respect to adaptation to illness. There were no significant differences in relapse rates among the three groups. At 1 year following treatment, the group receiving cognitively oriented psychotherapy maintained significantly better adaptation to their illness than the refusal group; however, the group differences were not maintained for the other outcomes, and there were no group differences in relapse rate or time to readmission (73). These findings are based on a quasi-experimental design and need to be interpreted with caution; nevertheless, the results suggest that individual cognitive behavior therapy may be beneficial in assisting patients to adjust to the experience of psychosis following remission of first-episode symptoms.

Individual cognitive behavior approaches have been developed to target specific challenges facing patients experiencing first-episode psychosis, such as suicidality, substance abuse, and persistent symptoms. In a study focusing on suicidal ideation and behavior in early psychosis, Power and colleagues (74) randomly assigned 56 suicidal individuals with nonaffective or affective first-episode psychosis in the Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre program to either LifeSPAN therapy plus the center’s other services or regular services without LifeSPAN therapy. LifeSPAN therapy is based on cognitively oriented psychotherapy for early psychosis as well as cognitive therapy for suicide, and it emphasizes distress management, problem-solving skills, identification of warning signs, and development of an aftercare plan. In addition, low self-esteem and feelings of hopelessness are specifically targeted. In this study, both groups improved on ratings of suicidal ideation and number of suicide attempts. However, the results showed an advantage for LifeSPAN therapy on self-reported hopelessness and quality of life at both 10 weeks posttreatment and 6-month follow-up. Power et al. concluded that adding cognitive behavior therapy to treatment for first-episode psychosis may lead to significant improvements in factors associated with suicide, such as hopelessness.

Edwards and colleagues at the Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre have developed cognitive behavior interventions targeting substance use and persistent psychotic symptoms (87, 88). One intervention focuses on reducing problematic cannabis use in individuals with first-episode psychosis and consists of psychoeducation, motivational interviewing, goal setting, and discussion about goal achievement and relapse prevention. A randomized, controlled trial comparing the cannabis and psychosis intervention with psychoeducation alone was conducted, and the preliminary results suggested that cannabis use in both groups decreased, with no clear advantages for the cannabis and psychosis intervention over psychoeducation alone (89). Edwards and colleagues have also developed “systematic treatment of persistent psychosis,” given that approximately 20% of individuals with first-episode psychosis may experience persistent psychotic symptoms (40). This therapy is based on the cognitively oriented psychotherapy for early psychosis at the Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre and is designed to facilitate recovery in patients experiencing persistent positive symptoms. A randomized, controlled trial evaluating the relative and combined effects of clozapine and systematic treatment of persistent psychosis in the treatment of individuals with persistent symptoms is currently being conducted at the Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre (88).

Other randomized, controlled studies of individual cognitive behavior therapy for first-episode psychosis have demonstrated the following benefits over routine care: fewer days spent in the hospital (75), reduced psychotic symptoms, fewer hospital admissions, increased insight, and better treatment adherence (76). The foregoing findings suggest that individual cognitive behavior therapy may provide some benefits in the treatment of first-episode psychosis, especially in the areas of symptom reduction, adaptation to one’s illness, and improvements in subjective quality of life. Most studies have not shown individual therapy to be effective in reducing relapses or rehospitalizations. Finally, the long-term findings are mixed; the follow-up data reported thus far have demonstrated some long-term benefits associated with individual therapy (e.g., references 71 and 73) but also suggest that some of the initial gains made in treatment may not persist over time (e.g., reference 73).

Group and Family Treatment

Unlike individual therapy, group treatment for first-episode psychosis does not appear to have been examined for efficacy in randomized, controlled studies. Quasi-experimental research has demonstrated benefits of group therapy with respect to prevention of illness-related deterioration and disability, especially for individuals with poor premorbid functioning (77). Additional uncontrolled studies have shown improved treatment adherence (78) and increased treatment satisfaction (79) associated with group participation. However, given the uncontrolled nature of these studies, these findings need to be interpreted with caution.

Family therapy for first-episode psychosis has been more systematically investigated. Linszen and colleagues (80) randomly assigned 76 outpatients to 12 months of behavioral family therapy (focusing on communication and problem-solving skills training) plus individual-oriented treatment (focusing on relapse prevention and psychoeducation) or individual-oriented treatment without family therapy. Both groups had recently been discharged after 3 months of inpatient treatment emphasizing integrated psychosocial and pharmacological treatment, and they were currently receiving outpatient medication management. After 1 year, there was no differential effect of the family treatment on relapse; the two groups had similar relapse rates, and the overall relapse rate was low (i.e., 16%). Five-year follow-up (81, 82) also indicated no added benefit of family treatment over individual treatment for relapse rates, and it showed that 65% of the patients in the total group with nonchronic symptoms relapsed at least once over the course of 5 years. In addition, this study showed no differential effect of family treatment on social functioning or expressed emotion. However, individuals who received family treatment spent significantly less time in hospitals and/or shelters.

Other research on family therapy for early psychosis has demonstrated more positive results. For example, Zhang and colleagues (83) randomly assigned 83 outpatients with first-episode psychosis to 18 months of family therapy and routine care or to routine care alone. The family therapy intervention consisted of family groups and individual family therapy sessions, and it emphasized psychoeducation, identification of warning signs, stress management, the importance of attributing maladaptive behavior to the illness (rather than to personality or “laziness”), communication skills training, and reduction of high expressed emotion (i.e., decreasing familial criticism, hostility, and overinvolvement). There was contact with the families at least once every 3 months, and families who did not attend appointments were visited in their homes. The results showed that the family intervention was associated with a significantly lower rate of hospital readmissions and fewer days spent in the hospital. Indeed, the authors concluded that the patients not receiving the family intervention were 3.5 times as likely to be readmitted to the hospital during the study period as the patients who did receive family therapy. This effect remained even after differences in medication compliance were controlled for. Further, the patients receiving family therapy who were not readmitted to the hospital demonstrated significant improvements in positive symptoms and social functioning. Additional research has shown similar favorable outcomes associated with family treatment, such as fewer hospital admissions, less time spent in the hospital, and symptom reduction (84).

Thus, while some research has indicated that family interventions in early psychosis are beneficial with respect to reducing relapse and improving clinical and functional status (e.g., reference 83), other findings have not been as encouraging (e.g., reference 80). More empirical work needs to be done before any firm conclusions can be made.

Finally, Drury and colleagues (90, 91) specifically evaluated the effects of a multimodal treatment approach combining individual and group cognitive behavior therapy with family therapy in the treatment of recent-onset acute psychosis. In a randomized, controlled trial, the combination treatment, compared with basic support and recreational activities, yielded faster and greater improvements of positive symptoms, reduced recovery time by 25%–50%, and led to improvements in insight, dysphoria, and “low-level” psychotic thinking (e.g., suspiciousness). In a 5-year follow-up, Drury et al. (92) found enduring positive effects for the combination therapy group relative to the control group; however, these benefits were predominantly observed in individuals who had experienced at most one relapse over the course of follow-up. The long-term benefits in this subgroup included fewer positive symptoms, less delusional conviction and thought disorder, and better subjective “control over illness.” While these findings are positive, this study has been criticized for methodological flaws in its design, such as nonblinded assessments (93) and baseline differences in medication doses between the two groups (94).

Discussion

The findings reviewed suggest that adjunctive psychosocial interventions for patients experiencing early psychosis are beneficial across a variety of domains and can assist with symptomatic and functional recovery. Research on multielement interventions indicates that following an initial episode of psychosis, these comprehensive treatment approaches may positively influence short-term outcomes, such as clinical status and social functioning, as well as time spent in the hospital and likelihood of hospital readmission. However, as noted in another recent review of this area (53), most of the research on multielement programs is based on quasi-experimental designs using historical (56, 58, 65, 66) or prospective (66) comparison groups or on single-group designs, which track the progress of one group over a specified period of time (33, 46, 57, 59–64). Indeed, there is still a paucity of randomized, controlled research in this area; thus, these findings need to be interpreted with caution. Other methodological issues making interpretation of these results challenging include subject heterogeneity (e.g., affective versus nonaffective first-episode psychosis) and varying definitions for certain outcomes, such as relapse and remission, across studies.

One important caveat regarding multielement interventions is that the scope of these programs makes them difficult to implement on a widespread basis, particularly in countries whose public health care systems do not support the necessary infrastructure or do not recognize best treatment practices for early psychosis (95). Indeed, given the wide range of services offered in these programs, it would be helpful to isolate the “effective ingredients” when evaluating a program’s utility. Understanding which elements are critical can help inform program development in areas currently lacking such specialized first-episode treatment services. Thus, the current findings in this area point to two important future research directions: 1) a greater number of randomized, controlled designs to provide a more stringent test of the efficacy of multielement programs and 2) utilization of research designs that will allow one to deconstruct the key ingredients of these programs and to determine the specific types of patients for whom these services are particularly beneficial. Single-element studies can be quite helpful in this regard.

With respect to research on single-element interventions, support for individual cognitive behavior therapy in early psychosis is modest yet encouraging, especially regarding symptom improvements (particularly positive symptoms), adaptation to one’s illness, and increased subjective quality of life (e.g., references 71–74). In addition, the majority of studies evaluating individual cognitive behavior therapy have used randomized, controlled designs. However, individual therapy has not been shown to be effective in reducing relapse or rehospitalization in early psychosis, and some findings suggest that early treatment gains may not be maintained over time.

No firm conclusions can yet be drawn from the literature on group and family therapies for this population. Group therapy is a widely used treatment modality for early psychosis, but to our knowledge, no randomized, controlled trials have been conducted. Research findings on family therapy in early psychosis have been mixed, with some studies documenting benefits with respect to symptoms, social functioning, and likelihood of rehospitalization (e.g., reference 83) and other studies having less favorable results (e.g., reference 80). One possible interpretation of these findings is that family interventions are indeed beneficial to individuals with early psychosis although they may not add significant benefit above and beyond concurrent individual therapy. Additional well-controlled research is needed to clarify the impact of family and group therapy in first-episode psychosis.

In general, while the research done to date on specific (i.e., single-element) psychosocial treatments for early psychosis is promising, there are few robust findings. Many of the aforementioned single-element studies were conducted in the context of large multielement programs (e.g., references 72–74); it is therefore difficult to yield robust additive effects of a specific intervention, when such a large degree of improvement is likely due to the impact of the program as a whole. Further, as with the literature on multielement treatments, significant obstacles to drawing broader conclusions with respect to specific psychosocial treatments for first-episode psychosis include the paucity of well-controlled studies, as well as methodological variation among studies (e.g., study group composition, definitions for remission and relapse).

Future work should take an increasingly integrative approach to psychosocial treatment, drawing on a variety of empirically validated treatment approaches to address the variety of challenges that individuals with first-episode psychosis experience (e.g., positive and negative symptoms, medication adherence, substance use, functional impairments). Indeed, future studies should place more emphasis on measuring functional recovery (i.e., social, work, and school functioning, recreation, and social relationships [96]) both during and after treatment. Despite demonstrated short-term benefits, the ability of psychosocial interventions delivered early in psychosis to effect long-term improvement, particularly with respect to social/occupational disability, is still unknown. Additional longitudinal research is needed to shed light on this question.

Some findings suggest that many of the initial benefits achieved in treatment may not be maintained over time in patients with first-episode psychosis (97). This may be addressed through greater efforts to improve ongoing engagement with available services (which is a significant challenge in the field of early psychosis [e.g., reference 98]) and to lengthen the duration of active interventions, if necessary. Studies of individuals with chronic schizophrenia suggest that longer-term treatments are often associated with more favorable outcomes (99). In addition, naturalistic studies of psychological treatments for a variety of nonpsychotic disorders have demonstrated that patients tend to show greater degrees of improvement with longer periods of treatment (100). Clinicians and researchers alike should utilize these findings to inform the delivery of psychosocial interventions in early psychosis. Ideally, these efforts will be successful at improving both short- and long-term outcomes, thus reducing the morbidity and mortality so often associated with this devastating illness.

|

|

|

Received Jan. 19, 2004; revision received Jan. 3, 2005; accepted Jan. 6, 2005. From the Department of Psychology and the Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina; the Department of Psychiatry, Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, N.H.; and the Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Penn, Department of Psychology, CB#3270, Davie Hall, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3270; [email protected] (e-mail).

1. Murray CJL, Lopez AD (eds): The Global Burden of Disease and Injury Series, vol 1: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability From Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1996Google Scholar

2. Davidson L, McGlashan TH: The varied outcomes of schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry 1997; 42:34–43Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Hegarty JD, Baldessarini RJ, Tohen M, Waternaux C, Oepan G: One hundred years of schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of the outcome literature. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1409–1416Link, Google Scholar

4. Kane JM: Management strategies for the treatment of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 1999:60(suppl 12):13–17Google Scholar

5. Wasylenki DA: The cost of schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry 1994; 39(9 suppl 2):S65-S69Google Scholar

6. Rice DP: The economic impact of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60(suppl 1):4–6Google Scholar

7. Thieda P, Beard S, Richter A, Kane J: An economic review of compliance with medication therapy in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2003; 54:508–516Link, Google Scholar

8. Wyatt RJ, Henter I, Leary MC, Taylor E: An economic evaluation of schizophrenia—1991. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1995; 30:196–205Medline, Google Scholar

9. Weiden PJ, Olfson M: Cost of relapse in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1995; 21:419–429Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Bottlender R, Sato T, Jaeger M, Wittman J, Strauss J, Moller HJ: The impact of the duration of untreated psychosis prior to first psychotic admission on the 15-year outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2003; 62:37–44Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Lieberman JA, Perkins D, Belger A, Chakos M, Jarskog F, Boteva K, Gilmore J: The early stages of schizophrenia: speculations on pathogenesis, pathophysiology, and therapeutic approaches. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 50:884–897Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Norman RMG, Malla A: Duration of untreated psychosis: a critical examination of the concept and its importance. Psychol Med 2001; 31:381–400Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Barnes T, Hutton S, Chapman M, Mutsatsa S, Puri B, Joyce E: West London first-episode study of schizophrenia: clinical correlates of duration of untreated psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 177:207–211Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Craig TJ, Bromet EJ, Fennig S, Tanenberg-Karant M, Lavelle J, Galambos N: Is there an association between duration of untreated psychosis and 24-month clinical outcome in a first-admission series? Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:60–66Link, Google Scholar

15. Ho B-C, Andreasen NC, Flaum M, Nopoulos P, Miller D: Untreated initial psychosis: its relation to quality of life and symptom remission in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:808–815; correction, 2001; 158:986Google Scholar

16. Lehtinen V, Aaltonen J, Koffert T, Räkköläinen V, Syvälahti E: Two-year outcome in first-episode psychosis treated according to an integrated model: is immediate neuroleptisation always needed? Eur Psychiatry 2000; 15:312–320Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Birchwood M, Todd P, Jackson C: Early intervention in psychosis: the critical period hypothesis. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1998; 33:53–59Google Scholar

18. Lieberman JA, Fenton WS: Delayed detection of psychosis: causes, consequences, and effect on public health (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1727–1730Link, Google Scholar

19. Lieberman JA, Sheitman B, Chakos M, Robinson D, Schooler N, Keith S: The development of treatment resistance in patients with schizophrenia: a clinical and pathophysiological perspective. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1998; 18(2 suppl 1):20S-24SGoogle Scholar

20. Shepherd M, Watt D, Falloon T, Smeeton N: The natural history of schizophrenia: a five-year follow-up study of outcome and prediction in a representative sample of schizophrenics. Psychol Med Monogr Suppl 1989; 15:1–46Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Stephenson J: Delay in treating schizophrenia may narrow therapeutic window of opportunity. JAMA 2000; 283:2091–2092Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Szymanski S, Lieberman JA, Alvir JM, Mayerhoff D, Loebel A, Geisler S, Chakos M, Koreen A, Jody D, Kane J, Woerner M, Cooper T: Gender differences in onset of illness, treatment response, course, and biologic indexes in first-episode schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:698–703Link, Google Scholar

23. Wiersma D, Nienhuis FJ, Sloof CJ: Natural course of schizophrenic disorders: a 15-year follow-up of a Dutch incidence cohort. Schizophr Bull 1998; 24:75–85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Lieberman JA, Alvir JMJ, Woerner M, Degreef G, Bilder R, Ashtari M, Bogerts B, Mayerhoff D, Loebel A, Levy D, Hinrichsen G, Szymanski S, Chakos M, Borenstein M, Kane JM: Prospective study of psychobiology in first episode schizophrenia at Hillside Hospital: design, methodology and summary of findings. Schizophr Bull 1992; 18:351–371Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Lieberman J, Chakos M, Wu H, Alvir J, Hoffman E, Robinson D, Bilder R: Longitudinal study of brain morphology in first episode schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 49:487–499Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Ho BC, Andreasen NC, Nopoulos P, Arndt S, Magnotta V, Flaum M: Progressive structural brain abnormalities and their structural relationship to clinical outcome: a longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study early in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:585–594Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Falloon IR, Kydd RR, Coverdale JH, Laidlaw TM: Early detection and intervention for initial episodes of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1996; 22:271–282Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. McGorry PD: The concept of recovery and secondary prevention of psychotic disorders. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1992; 26:3–17Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Wyatt RJ, Henter I: Rationale for the study of early intervention. Schizophr Bull 2001; 51:69–76Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Lieberman JA: Pathophysiologic mechanisms in the pathogenesis and clinical course of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60(suppl 12):9–12Google Scholar

31. Lieberman JA, Phillips M, Gu H, Stroup S, Zhang P, Kong L, Ji Z, Koch G, Hamer RM: Atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in treatment-naive first-episode schizophrenia: a 52-week randomized trial of clozapine vs chlorpromazine. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003; 28:995–1003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Tohen M, Strakowski SM, Zarate C, Hennen J, Stoll AL, Suppes T, Faedda G, Cohen BM, Gebre-Medhin P, Baldessarini RJ: The McLean-Harvard First-Episode Project: 6-month symptomatic and functional outcome in affective and nonaffective psychosis. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 48:467–476Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Addington J, Leriger E, Addington D: Symptom outcome 1 year after admission to an early psychosis program. Can J Psychiatry 2003; 48:204–207Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Lieberman JA, Jody D, Geisler S, Alvir J, Loebel A, Szymanski S, Woerner M, Borenstein M: Time course and biologic correlates of treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:369–376Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Whitehorn D, Brown J, Richard J, Rui Q, Kopala L: Multiple dimensions of recovery in early psychosis. Int Rev Psychiatry 2002; 14:273–283Crossref, Google Scholar

36. Addington J, Mansely C, Addington D: Weight gain in first episode psychosis. Can J Psychiatry 2003; 48:272–276Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Sanger TM, Lieberman JA, Tohen M, Grundy S, Beasley C Jr, Tollefson GD: Olanzapine versus haloperidol treatment in first-episode psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:79–87Link, Google Scholar

38. Coldham EL, Addington J, Addington D: Medication adherence of individuals with first episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002; 106:286–290Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Kasper S: First-episode schizophrenia: the importance of early intervention and subjective tolerability. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60(suppl 23):5–9Google Scholar

40. Edwards J, Maude D, Herrmann-Doig T, Wong L, Cocks J, Burnett P, Bennett C, Wade D, McGorry P: A service response to prolonged recovery in early psychosis. Psychiatr Serv 2002; 53:1067–1069Link, Google Scholar

41. Birchwood M: Pathways to emotional dysfunction in first-episode psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 2003; 182:373–375Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Birchwood M, Spencer E, McGovern D: Schizophrenia: early warning signs. Advances in Psychiatr Treatment 2000; 6:93–101Crossref, Google Scholar

43. Mueser KT, Rosenberg SD: Treating the trauma of first episode psychosis: a PTSD perspective. J Ment Health 2003; 12:103–108Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Erickson DH, Beiser M, Iacono WG, Fleming JAE, Lin TY: The role of social relationships in the course of first-episode and affective psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:1456–1461Link, Google Scholar

45. Grant C, Addington J, Addington D, Konnert C: Social functioning in first- and multiepisode schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry 2001; 46:746–749Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Addington J, Young J, Addington D: Social outcome in early psychosis. Psychol Med 2003; 33:1119–1124Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Priebe S, Roeder-Wanner UU, Kaiser W: Quality of life in first-admitted schizophrenia patients: a follow-up study. Psychol Med 2000; 30:225–230Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Gupta S, Andreasen NC, Arndt S, Flaum M, Hubbard WC, Ziebell S: The Iowa Longitudinal Study of Recent Onset Psychosis: one-year follow-up of first episode patients. Schizophr Res 1997; 23:1–13Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Svedberg B, Mesterton A, Cullberg J: First-episode non-affective psychosis in a total urban population: a 5-year follow-up. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2001; 36:332–337Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Malla AK, Norman RMG: Early intervention in schizophrenia and related disorders: advantages and pitfalls. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2002; 15:17–23Crossref, Google Scholar

51. Birchwood M, Spencer E: Early intervention in psychotic relapse. Clin Psychol Rev 2001; 21:1211–1226Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Spencer E, Birchwood M, McGovern D: Management of first-episode psychosis. Advances in Psychiatr Treatment 2001; 7:133–142Crossref, Google Scholar

53. Edwards J, Harris MG, Bapat S: Developing services for first-episode psychosis and the critical period. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2005; 48:s91-s97Google Scholar

54. Edwards J, Harris M, Herman A: The Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre, Melbourne, Australia: an overview, November, 2001, in Recent Advances in Early Intervention and Prevention in Psychiatric Disorders. Edited by Ogura C. Tokyo, Seiwa Shoten, 2002, pp 26–33Google Scholar

55. Edwards J, McGorry P: Implementing Early Intervention in Psychosis. London, Martin Dunitz, 2002Google Scholar

56. McGorry PD, Edwards J, Mihalopoulos C, Harrigan SM: EPPIC: an evolving system of early detection and optimal management. Schizophr Bull 1996; 22:305–326Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Power P, Elkins K, Adlard S, Curry C, McGorry P, Harrigan S: Analysis of the initial treatment phase in first-episode psychosis. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1998; 33:71–76Google Scholar

58. Carbone S, Harrigan S, McGorry PD, Curry C, Elkins K: Duration of untreated psychosis and 12-month outcome in first-episode psychosis: the impact of treatment approach. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999; 100:96–104Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59. Malla AK, Norman RMG, McLean TS, McIntosh E: Impact of phase-specific treatment of first episode psychosis on Wisconsin Quality of Life Index (client version). Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001; 103:355–361Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Malla AK, Norman RMG, Manchanda R, McLean TS, Harricharan R, Cortese L, Townsend LA, Schotlen DJ: Status of patients with first-episode psychosis after one year of phase-specific community-oriented treatment. Psychiatr Serv 2002; 53:458–463Link, Google Scholar

61. Malla AK, Norman RM, Manchanda R, Townsend L: Symptoms, cognition, treatment adherence and functional outcome in first-episode psychosis. Psychol Med 2002; 32:1109–1119Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62. Addington J, Addington D: Impact of an early psychosis program on substance use. Psychiatr Rehab J 2001; 25:60–67Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63. Addington J, Williams J, Young J, Addington D: Suicidal behavior in early psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2004; 109:116–120Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. Mintz AR, Addington J, Addington D: Insight in early psychosis: a 1-year follow-up. Schizophr Res 2004; 67:213–217Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65. Larsen TK, McGlashan TH, Johannessen JO, Friis S, Guldberg C, Haahr U, Horneland M, Melle I, Moe LC, Opjordsmoen S, Simonsen E, Vaglum P: Shortened duration of untreated first episode of psychosis: changes in patient characteristics at treatment. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1917–1919Link, Google Scholar

66. Cullberg J, Levander S, Holmqvist R, Mattsson M, Eieselgren IM: One-year outcome in first episode psychosis patients in the Swedish Parachute Project. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002; 106:276–285Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67. Nordentoft M, Jeppesen P, Abel M, Kassow P, Peterson L, Thorup A, Krarup G, Hemmingsten R, Jorgensen P: OPUS Study: suicidal behaviour, suicidal ideation and hopelessness among patients with first-episode psychosis: one-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2002; 43:S98-S106Google Scholar

68. Nordentoft M, Jeppesen P, Kassow P, Abel M, Petersen L, Thorup A, Cristensen T, Øhlenschlæger, Jørgensen P: OPUS Project: a randomized controlled trial of integrated psychiatric treatment in first-episode psychosis—clinical outcome improved (abstract). Schizophr Res 2002; 53(suppl 1):51Google Scholar

69. Haddock G, Tarrier N, Morrison AP, Hopkins R, Drake R, Lewis S: A pilot study evaluating the effectiveness of individual inpatient cognitive-behavioural therapy in early psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1999; 34:254–257Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

70. Lewis S, Tarrier N, Haddock G, Bentall R, Kinderman P, Kingdon D, Siddle R, Drake R, Everitt J, Leadley K, Benn A, Grazebrook K, Haley C, Akhtar S, Davies L, Palmer S, Faragher B, Dunn G: Randomised controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy in early schizophrenia: acute-phase outcomes. Br J Psychiatry 2002; 181:91–97Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

71. Tarrier N, Lewis S, Haddock G, Bentall R, Drake R, Kinderman P, Kingdon D, Siddle R, Everitt J, Leadley K, Benn A, Grazebrook K, Haley C, Akhtar S, Davies L, Palmer S, Dunn G: Cognitive-behavioural therapy in first-episode and early schizophrenia: 18-month follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2004; 184:231–239Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

72. Jackson H, McGorry P, Edwards J, Hulbert C, Henry L, Francey S, Maude D, Cocks J, Power P, Harrigan S, Dudgeon P: Cognitively-oriented psychotherapy for early psychosis (COPE): preliminary results. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1998; 33:93–100Google Scholar

73. Jackson H, McGorry P, Henry L, Edwards J, Hulbert C, Harrigan S, Dudgeon P, Francey S, Maude D, Cocks J, Power P: Cognitively oriented psychotherapy for early psychosis (COPE): a 1-year follow-up. Br J Clin Psychol 2001; 40(part 1):57–70Google Scholar

74. Power PJR, Bell RJ, Mills R, Herrman-Doig T, Davern M, Henry LY, Yuen HP, Khadermy-Deijo A, McGorry PD: Suicide prevention in first episode psychosis: the development of a randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy for acutely suicidal patients with early psychosis. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2003; 37:414–420Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

75. Jolley S, Garety P, Craig T, Dunn G, White J, Aitken M: Cognitive therapy in early psychosis: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychother 2003; 31:473–478Crossref, Google Scholar

76. Wang C, Li Y, Zhao Z, Pan M, Feng Y, Sun F, Du B: [Controlled study on long-term effect of cognitive behavior intervention on first episode schizophrenia.] Chinese Ment Health J 2003; 17:200–202 (abstract in English)Google Scholar

77. Albiston DJ, Francey SM, Harrigan SM: Group programmes for recovery from early psychosis. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1998; 33:117–121Google Scholar

78. Miller R, Mason SE: Using group therapy to enhance treatment compliance in first episode schizophrenia. Soc Work Groups 2001; 24:37–51Crossref, Google Scholar

79. Lecomte T, Leclerc T, Wykes T, Lecomte J: Group CBT for clients with a first episode of schizophrenia. J Cognitive Psychother 2003; 17:375–383Crossref, Google Scholar

80. Linszen D, Dingemans P, van der Does AJW: Treatment, expressed emotion, and relapse in recent onset schizophrenic disorders. Psychol Med 1996; 26:333–342Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

81. Lenior ME, Dingemans PMAJ, Linszen DH, De Haan L, Schene AH: Social functioning and the course of early-onset schizophrenia: five-year follow-up of a psychosocial intervention. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 179:53–58Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

82. Lenior ME, Dingemans PMAJ, Schene AH, Hart AAM, Linszen DH: The course of parental expressed emotion and psychotic episodes after family intervention in recent-onset schizophrenia: a longitudinal study. Schizophr Res 2002; 57:183–190Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

83. Zhang M, Wang M, Li J, Phillips MR: Randomised-control trial of family intervention for 78 first-episode male schizophrenic patients: an 18-month study in Suzhou, Jiangsu. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1994; 24:96–102Medline, Google Scholar

84. Lehtinen K: Need-adapted treatment of schizophrenia: a five-year follow-up study from the Turku project. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1993; 87:96–101Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

85. Johannessen JO, Larsen TK, McGlashan T, Vaglum P: Early identification in psychosis: the TIPS project, a multi-centre study in Scandinavia, in Psychosis: Psychological Approaches and Their Effectiveness. Edited by Martindale D, Bateman A, Crowe M, Margison F. London, Gaskell, 2000, pp 210–234Google Scholar

86. Yung AR, Organ BA, Harris MG: Management of early psychosis in a generic adult mental health service. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2003; 37:429–436Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

87. Elkins K, Hinton M, Edwards J: Cannabis and psychosis: a psychological intervention, in Psychological Interventions in Early Psychosis. Edited by Gleeson JFM, McGorry PD. Chichester, UK, John Wiley & Sons, 2004, pp 137–156 Google Scholar

88. Edwards J, Wade D, Herrmann-Doig T, Gee D: Psychological treatment of persistent positive symptoms in young people with first-episode psychosis. Ibid, pp 191–208Google Scholar

89. Edwards J, Hinton M, Elkins K, Anthanasopoulos O: Cannabis and first-episode psychosis: the CAP project, in Substance Misuse in Psychosis: Approaches to Treatment and Service Delivery. Edited by Graham H, Mueser KT, Birchwood M, Copello A. Chichester, UK, John Wiley & Sons, 2003, pp 283–304Google Scholar

90. Drury V, Birchwood M, Cochrane R, Macmillan F: Cognitive therapy and recovery from acute psychosis: a controlled trial, I: impact on psychotic symptoms. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 169:593–601Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

91. Drury V, Birchwood M, Cochrane R, Macmillan F: Cognitive therapy and recovery from acute psychosis: a controlled trial, II: impact on recovery time. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 169:602–607Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

92. Drury V, Birchwood M, Cochrane R: Cognitive therapy and recovery from acute psychosis: a controlled trial, III: five-year follow-up. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 177:8–14Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

93. Tarrier N: Cognitive behaviour therapy for schizophrenia—a review of development, evidence and implementation. Psychother Psychosom 2005; 74:136–144Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

94. Turkington D, Dudley R, Warman DM, Beck AT: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for schizophrenia: a review. J Psychiatr Pract 2004; 10:5–16Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

95. Jarskog LF, Mattioli MA, Perkins DO, Lieberman JA: First-episode psychosis in a managed care setting: clinical management and research. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:878–884Link, Google Scholar

96. Noordsy D, Torrey W, Mueser K, Mead S, O’Keefe C, Fox L: Recovery from severe mental illness: an intrapersonal and functional outcome definition. Int Rev Psychiatry 2002; 14:318–326Crossref, Google Scholar

97. Linszen D, Dingemans P, Lenior M: Early intervention and a five-year follow-up in young adults with a short duration of untreated psychosis: ethical implications. Schizophr Res 2001; 51:55–61Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

98. Jackson HJ, McGorry PD, Edwards J: Cognitively oriented psychotherapy for early psychosis: theory, praxis, outcomes, and challenges, in Social Cognition and Schizophrenia. Edited by Corrigan PW, Penn DL. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2001, pp 249–284Google Scholar

99. Pilling S, Bebbington P, Kuipers E, Garety P, Geddes J, Orbach G, Morgan C: Psychological treatments in schizophrenia, I: meta-analysis of family intervention and cognitive behaviour therapy. Psychol Med 2002; 32:763–782Medline, Google Scholar

100. Westen D, Novotny CM, Thompson-Brenner H: The empirical status of empirically supported psychotherapies: assumptions, findings, and reporting in controlled clinical trials. Psychol Bull 2004; 130:631–663Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar