Amygdala Response in Patients With Acute PTSD to Masked and Unmasked Emotional Facial Expressions

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study used functional magnetic resonance imaging to investigate amygdala response in patients with acute posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) to emotional expressions. METHOD: Thirteen medication-free individuals with acute PTSD and no axis I psychiatric comorbidity were scanned while viewing pictures of fearful or happy faces, presented above or below consciousness, with backward masking. RESULTS: There was a significant positive correlation between the severity of PTSD and the difference in amygdala responses between masked fearful and happy faces and a corresponding negative correlation for the difference between unmasked fearful and happy faces. CONCLUSIONS: These findings suggest that functional abnormalities in brain responses to emotional stimuli observed in chronic PTSD are already apparent in its acute phase.

A number of neuroimaging studies have reported enhanced activity in the amygdala—a key brain structure for emotional processing (1)—in individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in relation to healthy comparison subjects in response to pictures (2), trauma-related scripts (3), and masked fearful faces (4). However, these studies were conducted on participants with long-standing chronic PTSD, which is typically associated with pharmacological treatment and significant psychiatric axis I comorbidity, including major depressive disorder and alcohol and substance abuse (5). Thus, it remains to be determined to what extent the observed results are specific to PTSD as opposed to other factors (6).

In addition, the majority of PTSD studies to date to our knowledge have focused on negative emotions; therefore, it is not known whether there are any abnormal patterns of activity in PTSD associated with positive stimuli. Thus, in this study, we examined amygdala responses to faces depicting happy and fearful expressions, presented above and below awareness, in recently traumatized individuals suffering from acute PTSD. In particular, we tested whether there were any differential responses to positive and negative emotional expressions as a function of stimulus awareness and the severity of PTSD.

Method

Thirteen individuals (four men, mean age of all subjects=36 years, range=19–57) were recruited at the emergency department of a major hospital in Montreal. All participants were diagnosed with DSM-IV acute PTSD resulting from motor vehicle accidents, as determined by the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (7) (mean score=63.8, SD=19.2, range=42–93). The participants were not taking psychotropic medication, had not suffered traumatic brain injury (or loss of consciousness for >10 minutes), and did not have any lifetime history of other axis I psychiatric disorders, including major depression and alcohol and substance abuse, assessed by the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (8). Their current depressive symptoms were deemed negligible, according to the abridged version of the Beck Depression Inventory (mean score=6.7, SD=4.6, range=1–14). The participants were scanned 4–6 weeks after their exposure to the trauma.

The stimuli were gray-scale pictures of 10 individuals from the Ekman and Friesen set (9) depicting happy, fearful, or neutral expressions. Stimulus awareness was manipulated by using a backward-masking procedure. Each trial consisted of a sequential presentation of two faces: one (the target) was presented for 16 msec, immediately followed by another (the mask), presented for 100 msec. In half of the trials, the target was an emotional face (happy or fearful), and the mask was a neutral one, and in the other half, the target was neutral, and the mask was emotional. Thus, this was a two-by-two factorial design with respect to emotional expression: happy versus fearful and masked versus unmasked.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging scanning was conducted with a 1.5-T Siemens Sonata system (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) at the Montreal Neurological Institute. A total of 300 T2*-weighted echo planar image volumes, with blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) contrast (30 slices covering the entire brain, 4-mm resolution, TR=2.54 seconds), were acquired during a single session.

Image processing and statistical analysis were performed by using SPM 99 (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, Institute of Neurology, University College, London), according to standard procedures. Briefly, the imaging time series was realigned to the first volume to correct for interscan movement, spatially normalized to a common Montreal Neurological Institute template to allow for group analysis, and spatially smoothed (8-mm full-width at half-maximum Gaussian kernel).

Data were analyzed by using a general linear model for each voxel in a two-stage random effects procedure, with the mean-corrected Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale scores as a covariate. A corrected p=0.05 was used, except within the amygdala, where we used p<0.001 (uncorrected) based on previous studies and our a priori hypothesis on its involvement in the processing of emotional facial expressions. In this report, we focus solely on responses observed within the amygdala.

Results

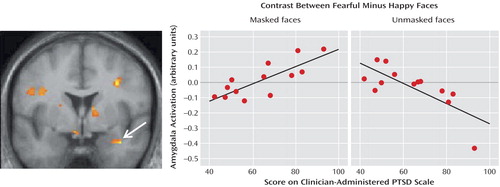

Figure 1 shows the region, located within the right lateral amygdala (x=38, y=0, z=–22) and extending into the substantia innominata, where the individuals’ PTSD scores were significantly correlated with the difference in BOLD responses between masked fear and masked happy faces (z=3.26, R2=0.66, p=0.0006). A scatterplot of the data for all subjects is also shown in Figure 1. Of interest, this region showed an opposite correlation (x=36, y=0, z=–22) (z=3.31, R2=0.52, p=0.0005) for the contrast involving unmasked faces, as shown in Figure 1. That is, the lateral amygdala had a negative correlation in the contrasts showing fearful minus happy faces when the happy faces were presented unmasked and therefore consciously perceived. In other words, the amygdalas of individuals with high PTSD symptoms responded more strongly to masked fearful and to unmasked happy facial expressions.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the previously observed enhanced right amygdala responses to masked fearful faces associated with chronic PTSD are already present in the acute phase as early as 1 month posttrauma. Of importance, the present study overcomes some of the limitations of previous studies by using an event-related design in a medication-free population without significant psychiatric comorbidity. Furthermore, the observed correlation between amygdala activity and PTSD scores suggests that the previously observed abnormal brain responses in patients with severe chronic PTSD may represent the upper end of a continuum rather than a discrete, qualitatively distinct phenomenon (10). Future studies including symptomatic individuals who do not fulfill all the clinical criteria for PTSD diagnosis should further elucidate this important issue.

Although the exact nature of the laterality of amygdala responses to emotional stimuli is still under debate, our observed right amygdala activation is consistent with the previously reported enhancement of right amygdala responses to fearful faces in PTSD (4). In contrast, studies using linguistic material have shown increased left amygdala activation (e.g., reference 3).

An unexpected finding was the increased amygdala activation for unmasked happy faces, compared to fearful ones, as a function of symptom severity. Although this novel result requires further investigation and replication before definitive conclusions can be drawn, our finding may shed light on the often observed emotional numbing associated with PTSD, particularly the inability to fully experience positive emotions (11).

A large neuroimaging literature exists on the processing of facial expressions in healthy individuals as well as in neurologically ill and psychiatric populations. Thus, the use of these trauma-unrelated stimuli to study PTSD may allow for a more direct comparison of brain activity between different pathologies, thus helping to identify the possible common substrates—and differences—underlying various anxiety disorders involving a dysfunction of the fear system.

Received May 14, 2004; revision received Aug. 25, 2004; accepted Sept. 9, 2004. From the Douglas Hospital Research Centre; and the Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Montreal. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Armony, Douglas Hospital Research Centre, 6875 LaSalle Blvd., F.B.C. Pavilion, Verdun, Quebec H4H 1R3, Canada; [email protected] (e-mail).

Figure 1. Statistical Parametric Map of the Brain and Scatterplots Depicting the Amygdala in Patients With Acute PTSDa

aThe leftmost image shows the voxels within the amygdala in which the difference in responses to masked fearful and happy faces was significantly correlated with the severity of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as indexed by scores on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. The graphs show responses for masked fear minus masked happy faces and unmasked fear minus unmasked happy faces, as a function of PTSD severity.

1. LeDoux JE: Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci 2000; 23:155–184Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hendler T, Rotshtein P, Yeshurun Y, Weizmann T, Kahn I, Ben-Bashat D, Malach R, Bleich A: Sensing the invisible: differential sensitivity of visual cortex and amygdala to traumatic context. Neuroimage 2003; 19:587–600Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Shin LM, Orr SP, Carson MA, Rauch SL, Macklin ML, Lasko NB, Peters PM, Metzger LJ, Dougherty DD, Cannistraro PA, Alpert NM, Fischman AJ, Pitman RK: Regional cerebral blood flow in the amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex during traumatic imagery in male and female Vietnam veterans with PTSD. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:168–176Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Rauch SL, Whalen PJ, Shin LM, McInerney SC, Macklin ML, Lasko NB, Orr SP, Pitman RK: Exaggerated amygdala response to masked facial stimuli in posttraumatic stress disorder: a functional MRI study. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 47:769–776Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Jacobsen LK, Southwick SM, Kosten TR: Substance use disorders in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1184–1190Link, Google Scholar

6. Semple WE, Goyer PF, McCormick R, Donovan B, Muzic RF Jr, Rugle L, McCutcheon K, Lewis C, Liebling D, Kowaliw S, Vapenik K, Semple MA, Flener CR, Schulz SC: Higher brain blood flow at amygdala and lower frontal cortex blood flow in PTSD patients with comorbid cocaine and alcohol abuse compared with normals. Psychiatry 2000; 63:65–74Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, Keane TM: The development of a Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. J Trauma Stress 1995; 8:75–90Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC: The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(suppl 20):22–33Google Scholar

9. Ekman P, Friesen WV: Pictures of Facial Affect. Palo Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1976Google Scholar

10. Ruscio AM, Ruscio J, Keane TM: The latent structure of posttraumatic stress disorder: a taxometric investigation of reactions to extreme stress. J Abnorm Psychol 2002; 111:290–301Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Litz BT, Gray MJ: Emotional numbing in posttraumatic stress disorder: current and future research directions. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2002; 36:198–204Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar