Prevalence and Predictors of Depression Treatment in an International Primary Care Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of the study was to evaluate the prevalence and predictors of depression treatment in a diverse cross-national sample of primary care patients. METHOD: At primary care facilities in six countries (Spain, Israel, Australia, Brazil, Russia, and the United States), a two-stage screening process was used to identify 1,117 patients with current depressive disorder. At baseline, all patients completed a structured diagnostic interview as well as measures of anxiety symptoms, alcohol use, chronic comorbid physical conditions, and perceived barriers to treatment. Primary care physicians were advised if the research interview indicated a probable depressive disorder in their patients. Three and 9 months later, participants reported all health services (including specialty mental health care and antidepressant medication) used in the preceding 3 months. RESULTS: Across the six sites, the proportion of patients receiving any antidepressant pharmacotherapy ranged from a high of 38% in Seattle to a low of 0% in St. Petersburg; the proportion receiving any specialty mental health care varied from a high of 29% in Melbourne to a low of 3% in St. Petersburg. Patient characteristics were not consistently associated with receipt of either pharmacotherapy or specialty mental health care. Out-of-pocket cost was the most commonly reported barrier to treatment for depression; the percentage of patients who reported this barrier ranged from 24% in Barcelona to 75% in St. Petersburg. CONCLUSIONS: Depression screening and physician notification are not sufficient to prompt adequate treatment for depression. The probability of treatment may be more influenced by characteristics of health care systems than by the clinical characteristics of individual patients. Financial barriers may be more important than stigma as impediments to appropriate care.

Data collected in the United States and Western Europe demonstrate shortcomings in the primary care management of depression (1–3). Many patients with significant depressive disorders go unrecognized (4), and recognition may not lead to effective treatment (3, 5). Among patients initiating either pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy, few receive levels of treatment consistent with research evidence and expert guidelines (3, 6). Overall, less than one-quarter of primary care patients with depressive disorders receive adequate acute-phase treatment (1, 3, 5).

Among depressed primary care patients, nontreatment or undertreatment has been associated with specific patient, physician, and health system characteristics. Patient characteristics include less severe depression (7), male sex (8, 9), and minority ethnicity (10–12). Associations between age and antidepressant treatment have been inconsistent (8, 9). Rates of depression treatment also vary widely among physicians (13–15), with some evidence for higher rates among physicians with more thorough training or favorable attitudes toward treatment of mental disorders (8, 16). Recognition and treatment of depression appear more frequent in primary care settings with greater continuity of care and more personal doctor-patient relationships (8, 17). Financial barriers (absence of insurance coverage, higher out-of-pocket costs) are associated with lower rates of antidepressant treatment (18) and specialty mental health utilization (19, 20).

Limited data are available regarding treatment of depression in primary care outside of the United States and Western Europe. Ten years ago, the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) 15-site collaborative study of Psychological Problems in General Health Care reported that fewer than one-third of patients with depressive disorders diagnosed by research interviews received any antidepressant treatment, with a range across study sites of 0% to 46% (7). Benzodiazepines were prescribed as frequently as antidepressants (7, 8). No data were available regarding dose or duration of antidepressant treatment. In addition, the WHO study did not collect data on use of psychotherapy or other specialty mental health care.

This report uses data from the Longitudinal Investigation of Depression Outcomes (LIDO) study to examine treatment received by depressed patients in six diverse primary care sites. The LIDO project extended previous work by collecting systematic data on use of specialty mental health care, dose of antidepressant treatment, and patient-reported barriers to treatment. We use these data to examine three questions: What proportion of primary care patients with current depressive disorder receives specific treatment (pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy)? What patient characteristics are associated with receipt of treatment? What barriers might account for nontreatment or undertreatment of depression?

Method

The LIDO project was a longitudinal study of depressive symptoms, quality of life, and health services use among primary care patients in Barcelona (Spain), Be’er Sheva (Israel), Melbourne (Australia), Porto Alegre (Brazil), St. Petersburg (Russia), and Seattle (United States). Methods are described in detail elsewhere (21, 22) and are summarized here. At each site, investigators identified one or more primary care clinics considered typical of local primary health care delivery (e.g., not academic or teaching clinics, no specific focus on mental health care, generally representative in sociodemographic characteristics). As described in earlier publications (21, 23), clinics varied widely in style of primary care practice, typical treatment of depression, and availability of specialty mental health care. Characteristics of participating clinics are summarized in Table 1.

At each site, consecutive adult (age 18–75 years) visitors were invited to participate in a study of physical health, emotional health, and quality of life. After providing informed consent, participants completed a screening questionnaire that included the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale (24), the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey Functional Status Questionnaire (25), and questions regarding treatment for depression (e.g., “Any medications or therapy for depression?”) in the last 3 months. Patients were considered eligible for a second-stage diagnostic assessment on the basis of the following criteria: CES-D Scale score of 16 or greater, no depression treatment in the past 3 months, and no plans to move from the area during the next 12 months. In primary care samples, this CES-D Scale threshold has shown sensitivity of approximately 80% and specificity of approximately 75% in identifying current major depression (26). Each site continued screening until approximately 200 patients were enrolled in the longitudinal study (described later in this section). Table 1 displays the proportion of patients at each site with CES-D Scale scores ≥16 and the proportion of “screen-positive” patients excluded because of recent depression treatment. Across all sites, 18,456 patients completed screening and 4,662 were eligible for the second-stage diagnostic interview. All participants provided written informed consent for participation in the diagnostic assessment and longitudinal study.

The second-stage assessment included the depressive disorders module of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (27), the anxiety subscale extracted from the Hopkins Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90) (28), a checklist of chronic physical conditions, a six-item yes/no questionnaire regarding perceived barriers to receiving health care, questions regarding frequency and quantity of alcohol use (29), and other measures not described here. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview is a completely structured diagnostic assessment instrument developed for use in cross-national epidemiologic studies. Of the 4,662 eligible patients, 2,359 (51%) completed the diagnostic assessment and 49% either refused or failed to keep assessment appointments. Compared to those completing the baseline assessment, nonparticipants were slightly younger (mean of 40.5 years versus 41.6 years), more likely to be male (35% versus 31.4%), less educated (mean of 11.2 years versus 11.8 years), and less distressed as measured by the CES-D Scale score (mean of 24.7 versus 26.4) or the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey mental component score (mean of 43.7 versus 42.6). While all of these comparisons were statistically significant (p<0.01 for all, t tests for continuous measures or chi-square tests for proportions), all were small in practical or clinical terms. Of those completing the baseline assessment, 1,193 patients (51%) met DSM-IV criterion A for current major depressive episode and were invited to enroll in the longitudinal study; 1,117 (94% of those eligible) agreed to do so.

For all patients enrolled, the treating primary care physician received a letter reporting that the research interview “indicated a probable diagnosis of depression,” but no specific treatments were recommended.

All participants in the longitudinal study were asked to complete reassessments after 6 weeks, 3 months, 9 months, and 12 months. The 3- and 9-month assessments included a detailed questionnaire regarding health service use during the prior 3 months. This Resource Use Questionnaire (30) assessed names and doses of all medications and all use of specialty mental health services (outpatient visits, day treatment or day hospital, and inpatient services) for two 3-month periods (months 1 through 3 and months 7 through 9 after enrollment). Of the patients who entered the longitudinal study, 93% completed the 3-month assessment and 87% completed the 9-month assessment.

The minimum criteria for potentially effective antidepressant doses were based on the lower end of the dosing ranges recommended in the U.S. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research guidelines (31) for treatment of depression in primary care (e.g., 75 mg/day for imipramine, 20 mg/day for fluoxetine). For drugs not included in the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research guidelines, equivalent doses were estimated by study investigators (Appendix 1). For specialty mental health care, a “potentially effective” level of treatment was defined as three or more visits in a 3-month period, slightly below the lowest level of treatment found effective in primary care randomized trials (32, 33).

Participants reporting any one of 12 chronic physical conditions were considered to have a chronic comorbid physical condition. Participants scoring 1.7 or higher on the SCL-90 anxiety scale were considered to have comorbid anxiety disorder. Participants reporting either binge drinking (more than 6 drinks on one occasion) at least once a month or a high level of regular alcohol use (more than 14 drinks per week for women, more than 21 drinks per week for men) were considered to have an “at risk” drinking pattern.

These analyses include data for all patients who completed the baseline, 3-month, and 9-month assessments. Comparisons of proportions across sites were made by using chi-square tests. Predictors of treatment within sites were examined by using separate logistic regression models for each site. A 5% threshold (two-sided) for statistical significance was used throughout. All analyses were performed with the SPSS software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago).

Results

The proportions of patients receiving various treatments at each site are shown in Table 2. Rates of specialty mental health visits and pharmacotherapy varied widely, and the proportion exposed to any treatment ranged from 3% in St. Petersburg to 49% in Seattle. At no site did the proportion of patients who received potentially effective depression treatment exceed 40%. Antidepressant pharmacotherapy was more common than specialty mental health care in Barcelona and Seattle, while the opposite pattern was seen in Be’er Sheva and Melbourne. Because lack of treatment might be appropriate when depression resolves spontaneously, subgroup analyses were used to examine rates of treatment among those with persistent depressive symptoms (CES-D Scale score ≥16) after 9 months (N=345). In this subgroup, the proportion receiving any antidepressant treatment ranged from 37% in Seattle to 0% in St. Petersburg (χ2=34.9, df=5, p<0.001), the proportion with any specialty mental health contact ranged from 31% in Melbourne to 4% in St. Petersburg (χ2=37.6, df=5, p<0.001), and the proportion receiving any treatment ranged from 48% in Seattle to 4% in St. Petersburg (χ2=37.2, df=5, p<0.001). Rates of benzodiazepine use were below 15% at all sites. Among those with an SCL-90 anxiety score ≥1.7, the proportion reporting any benzodiazepine use ranged from 25% in Barcelona to 0% in Porto Alegre, St. Petersburg, and Barcelona.

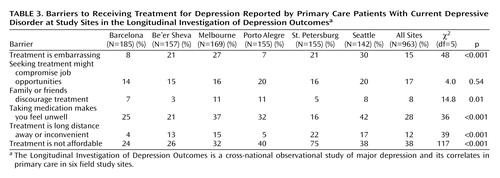

Table 3 displays patient-reported barriers to receiving treatment at each site. Concern about costs was the most common barrier and ranked first or second at every site. Concerns about adverse effects of medication were the second most common perceived barrier overall and were among the top three barriers at every site except St. Petersburg. Stigma-related barriers (perception of potential effects of treatment on job opportunities) were less common, with overall prevalence rates of 14%–20%. Financial barriers were reported most often in St. Petersburg, while concern about adverse medication effects was most common in Seattle. To simplify further analyses, data on barriers to treatment were collapsed into three categories: cost and travel barriers (includes “treatment is not affordable” and “treatment is a long distance away or inconvenient”), stigma-related barriers (includes “treatment is embarrassing,” “seeking treatment might compromise job opportunities,” and “family or friends discourage treatment”), and concerns about adverse effects of medication (includes “taking medication makes you feel unwell”).

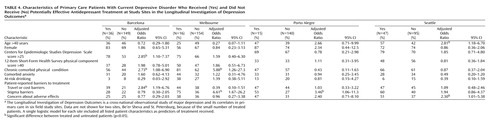

Table 4 shows baseline characteristics of patients who did and did not receive antidepressant pharmacotherapy at a potentially effective dose. Of the 40 comparisons, seven were significant at the 5% level. Severity of depression was significantly associated with adequate antidepressant treatment at only one of the four sites examined. Patient-reported barriers were not consistently associated with use of antidepressant drugs within sites, and the few significant relationships were the opposite of those predicted (more self-reported barriers among those treated). If the threshold p value was adjusted to 0.00125 to account for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni correction), then none of the observed differences would be considered statistically significant.

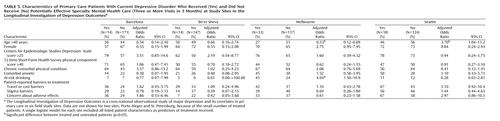

Table 5 displays baseline characteristics of patients who did and did not make three or more visits to a specialty mental health provider. Of 40 comparisons, only three were statistically significant at the 5% level (approximately the number expected by chance). The mean CES-D Scale score was higher among treated patients at three sites, but this difference was not statistically significant at any site. If the threshold p value was adjusted to 0.00125 to account for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni correction), then none of the observed differences would be considered statistically significant.

Discussion

Among primary care patients with previously untreated depression, the proportion receiving a potentially effective treatment over the next 9 months varied widely across study sites—from 1% in St. Petersburg to 40% in Seattle. Within sites, demographic or clinical characteristics were relatively weak predictors of treatment. Judging by patients’ reports, out-of-pocket cost appears to be the most frequent barrier to receiving care.

Several limitations must be considered in interpreting these findings. First, study sites were selected for diversity (of patient populations and health care systems) and were not intended to represent any specific range of culture or health care delivery. Second, study clinics were selected to be representative of local rather than national primary health care. At best, our results generalize to cities or regions rather than countries. Third, our data regarding treatment received are limited in detail. We have no data regarding antidepressant use between the periods covered by the 3- and 9-month assessments and no data regarding the content of mental health visits (e.g., whether patients received a type of psychotherapy proven effective). Fourth, our data on barriers to care were drawn from general questions regarding medical treatment rather than questions on specific aspects of depression treatment. Fifth, we relied on patients’ recall of treatment rather than records or claims data. Previous research has found that recall of services over 3 months is generally good, but not perfect (34). Sixth, those who declined to complete the screening or the baseline assessment might differ from those included in the sample. Finally, we would not draw any conclusions about effectiveness of treatment based on these data. Comparisons of treated and untreated patients using observational data are subject to significant bias given the bidirectional relationship between treatment and severity of illness (i.e., treatment can reduce severity of depression, but more severe depression may prompt more intensive treatment) (35).

Our sample size (approximately 160 patients at each site, including fewer than 50 treated patients) allows only limited power to examine patient-level predictors of treatment. As shown in Table 4 and Table 5, modest differences (such as 5-point differences in CES-D Scale scores) did not reach the 5% level of statistical significance. While pooling data across sites would increase statistical power, we see two arguments against a pooled analysis. First, pooling would require questionable assumptions about homogeneity across sites. For example, age and sex (which might be presumed to have similar meaning across sites) have quite variable relationships to receipt of treatment, indicating that pooling is probably inappropriate. Second, the wide variation in treatment rates across sites would confound patient characteristics with site differences. For example, Seattle and Barcelona contributed the bulk of patients treated with antidepressants, while St. Petersburg and Be’er Sheva contributed almost none. A pooled analysis of the predictors of antidepressant use might tell us more about differences between primary care patients in Seattle and St. Petersburg (ecological association) than about patient characteristics predicting depression treatment (true association).

Some of the predictors (such as cost-related or stigma-related barriers) may operate primarily as site-level factors rather than as patient-level factors. While these characteristics were not significantly associated with the probability of receiving treatment within sites (Table 4 and Table 5), they may account for differences observed between sites. For example, cost barriers were reported most often in St. Petersburg and Porto Alegre, two sites with low rates of overall treatment and the lowest rates of specialty mental health care. As discussed earlier, our data do not allow us to definitively distinguish between ecological and true associations.

We should emphasize two important characteristics of our study sample. First, patients who reported current depression treatment at the screening assessment were excluded from the longitudinal study. As shown in Table 1, the proportion of screen-positive patients already treated for depression was greater than 10% at all sites except Be’er Sheva. Second, primary care physicians were informed regarding each patient’s diagnosis of current depressive disorder. Therefore, our results indicate the proportion of “recognized” patients who receive treatment rather than the proportion of depressed patients normally recognized. The observed low treatment rates reflect the many points of potential failure between notifying physicians about screening results and patients’ eventual receipt of appropriate treatment: the physician may disagree with the screening result, the patient may not return, competing priorities may take precedence, the patient and physician may decide that no specific treatment is necessary, the patient may not accept the physician’s treatment recommendation, or the patient may not be able to afford recommended treatment. Our findings are consistent with those of several other studies (36–38) that simple feedback of depression screening results is not sufficient to ensure effective treatment or improved outcomes. Recognition of depression must be followed by affordable, appropriate, and sustained treatment.

In contrast to some previous studies (7, 39), we found relatively low rates of benzodiazepine use among depressed primary care patients. This finding may reflect the particular characteristics of the study sites or a general trend toward decreasing use of benzodiazepines. Consistent with previous studies, rates of benzodiazepine use varied widely across sites (7).

Given our generous criteria for potentially effective treatment, these rates should be considered upper bound estimates. For example, our dosing criteria reflected the lowest dose likely to be effective among primary care patients. Many patients require substantially higher doses. Similarly, the criterion of three or more specialty visits in 3 months represents a minimal level of care—without even considering the content of those visits. These generous criteria were intended to identify any potentially effective treatment (high sensitivity, low specificity) rather than treatment likely to be effective for most patients.

Data on barriers to treatment yielded a few unexpected findings. First, financial barriers were reported much more commonly than were barriers related to stigma. At all sites, concern about out-of-pocket costs was reported more often than any stigma-related concern. Second, concern about adverse effects of medication was the first or second most frequently reported barrier at all sites except St. Petersburg. Given low rates of treatment at many sites, it is likely that concerns about adverse effects of medication were based on preconception rather than experience. Third, rates of reported stigma-related barriers were highest in Seattle rather than in sites with lower overall treatment rates. This finding is remarkable, given that Seattle had the highest overall treatment rates and that stigmatization of depression or other mental disorders is often thought to be greater outside the United States and Western Europe. Fourth, cost was by far the most commonly cited barrier in St. Petersburg, the site with the lowest rate of depression treatment.

We should acknowledge that our data do not thoroughly examine stigma or cultural barriers to treatment. Doing so would require more detailed exploration of patients’ perceptions, attitudes, and explanatory models, as well as study of community residents who do not seek help in primary care.

Although study site was strongly associated with treatment, patient characteristics were relatively weak predictors. In general, higher CES-D Scale scores were associated with greater probability of using either type of treatment, but the relationship was statistically significant only in two of 12 comparisons. We also did not observe differential predictors—characteristics predicting receipt of pharmacotherapy rather than specialty mental health visits or the reverse. We cannot, of course, examine patient-level predictors of treatment at sites with very low treatment rates (e.g., we cannot examine the effect of cost barriers in St. Petersburg).

Our most striking finding was the 10-fold variation in probability of receiving treatment across study sites. Compared to this large variation, the variability within study sites was relatively small. Our data (Table 4 and Table 5) do not suggest that cross-site variability in patients’ demographic or clinical characteristics accounts for large cross-site differences in treatment rates. Instead, we must look to differences in health care systems to explain large variations in treatment. The WHO primary care survey suggested that cultural differences (how patients present to physicians, physicians’ attitudes regarding care of mental disorders) were important factors in the recognition and treatment of depression in primary care (17, 40). Our data suggest that patients perceive cost barriers (out-of-pocket costs) and practical barriers (absolute availability of treatments, time or distance to treatment) as major obstacles to treatment. Attributing low rates of treatment primarily to cultural or attitudinal barriers may lead to nihilism about concrete solutions. Fortunately, cost barriers or practical barriers should be more amenable to specific policy actions (such as changes in reimbursement for mental health care or location of mental health services) than are cultural or attitudinal barriers.

|

|

|

|

|

Received Aug. 6, 2002; revisions received Jan. 27 and Oct. 14, 2003; accepted Nov. 18, 2003. From the Center for Health Studies, Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound; Federal University of the State of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil; Universidad Internacional de Cataluña, Barcelona, Spain; and Health Research Associates, Seattle. Address reprint requests to Dr. Simon, Center for Health Studies, 1730 Minor Ave., Number 1600, Seattle, WA 98101; [email protected] (e-mail).The Longitudinal Investigation of Depression Outcomes (LIDO) study was a cross-national observational study of major depression and its correlates carried out in six field study centers. Development and conduct of the study was a collaborative effort between the research team, a panel of study advisers, and the site investigators in each of the six field centers. The overall study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company, and Health Research Associates, Inc., served as the international coordinating agency for the study. The LIDO Group research team consisted of Donald Patrick (University of Washington, Seattle); Don Buesching, Carol Andrejasich, and Michael Treglia (Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis); Mona Martin and Don Bushnell (Health Research Associates, Inc., Seattle); Diane Jones-Palm (Health Research Associates, European Office, Frankfurt, Germany); Stephen McKenna (Galen Research, Manchester, England); and John Orley and Rex Billington (World Health Organization, Mental Health Division, Geneva). The LIDO Group study advisers were Greg Simon (Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, Seattle), Daniel Chisholm and Martin Knapp (Institute of Psychiatry, London), Diane Whalley (Galen Research, Manchester, England), and Paula Diehr (University of Washington, Seattle). The LIDO Group site investigators were Helen Herrman (University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia), Marcelo Fleck (Federal University of the State of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil), Marianne Amir (Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Be’er Sheva, Israel), Ramona Lucas (Universidad Internacional de Cataluña, Barcelona, Spain), Aleksandr Lomachenkov (V.M. Bekhterev Psychoneurological Research Institute, St. Petersburg, Russia), and Donald Patrick (University of Washington, Seattle).

|

1. Goldman L, Nielsen N, Champion H: Awareness, diagnosis, and treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med 1999; 14:569–580Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hirschfeld R, Keller MB, Panico S, Arons BS, Barlow D, Davidoff F, Endicott J, Froom J, Goldstein M, Gorman JM, Guthrie D, Marek RS, Maurer TA, Meyer R, Phillips K, Ross J, Schwenk TL, Sharfstein SS, Thase ME, Wyatt RJ: The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association Consensus Statement on the Undertreatment of Depression. JAMA 1997; 277:333–340Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Young A, Klapp R, Sherbourne C, Wells K: The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:55–61Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Simon G, Goldberg D, Tiemens B, Ustun T: Outcomes of recognized and unrecognized depression in an international primary care study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1999; 21:97–105Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Goldberg D, Privett M, Ustun T, Simon G, Linden M: The effects of detection and treatment on the outcome of major depression in primary care: a naturalistic study in 15 cities. Br J Gen Pract 1998; 48:1840–1844Medline, Google Scholar

6. Simon G, Von Korff M, Rutter C, Peterson D: Treatment process and outcomes for managed care patients receiving new antidepressant prescriptions from psychiatrists and primary care physicians. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:395–401Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Linden M, Lecrubier Y, Bellantuono C, Benkert O, Kisely S, Simon G: The prescribing of psychotropic drugs by primary care physicians: an international collaborative study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1999; 19:132–140Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Kisely S, Linden M, Bellantuono C, Simon G, Jones J: Why are patients prescribed psychotropic drugs by general practitioners? results of an international study. Psychol Med 2000; 30:1217–1225Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Sclar D, Robinson L, Skaer T, Galin R: What factors influence the prescribing of antidepressant pharmacotherapy? an assessment of national office-based encounters. Int J Psychiatry Med 1998; 28:407–419Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Cornwell J, Hull S: Do GPs prescribe antidepressants differently for South Asian patients? Fam Pract 1998; 15(suppl 1):S16-S18Google Scholar

11. Skaer T, Sclar D, Robinson L, Galin R: Trends in the rate of depressive illness and use of antidepressant pharmacotherapy by ethnicity/race: an assessment of office-based visits in the United States, 1992–1997. Clin Ther 2000; 22:1575–1589Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Blazer DG, Hybels CF, Simonsick EM, Hanlon JT: Marked differences in antidepressant use by race in an elderly community sample: 1986–1996. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1089–1094Link, Google Scholar

13. Pharoah P, Melzer D: Variation in prescribing of hypnotics, anxiolytics, and antidepressants between 61 general practices. Br J Gen Pract 1995; 45:595–599Medline, Google Scholar

14. Hull S, Cornwell JHC, Eldridge S, Bare P: Prescribing rates for psychotropic medication among East London general practices. Fam Pract 2001; 18:167–173Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Ornstein S, Stuart G, Jenkins R: Depression diagnoses and antidepressant use in primary care practices: a study from the Practice Partner Research Network. J Fam Pract 2000; 49:68–72Medline, Google Scholar

16. Main D, Lutz L, Barrett J, Matthew J, Miller R: The role of primary care clinician attitudes, beliefs, and training in the diagnosis and treatment of depression. Arch Fam Med 1993; 2:1061–1066Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Ustun T, VonKorff M: Primary mental health services: access and provision of care, in Mental Illness in General Health Care: An International Study. Edited by Ustun T, Sartorius N. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1995, pp 347–360Google Scholar

18. Melfi C, Croghan T, Hanna M: Access to treatment for depression in a Medicaid population. J Health Care Poor Underserved 1999; 10:201–215Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Simon GE, Grothaus L, Durham ML, VonKorff M, Pabiniak C: Impact of visit copayments on outpatient mental health utilization by members of a health maintenance organization. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:331–338Link, Google Scholar

20. Landerman LR, Burns BJ, Swartz MS, Wagner HR, George LK: The relationship between insurance coverage and psychiatric disorder in predicting use of mental health services. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1785–1790Link, Google Scholar

21. Chisholm D, Amir M, Fleck M, Hermann H, Lomachenlov A, Lucas R, Patrick D: Longitudinal investigation of depression outcomes (the LIDO Study) in primary care in six countries: comparative assessment of local health systems and resource utilization. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2001; 10:59–71Crossref, Google Scholar

22. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder (Revision). Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159(April suppl)Google Scholar

23. Herman H, Patrick DL, Diehr P, Martin ML, Fleck M, Simon GE, Buesching DP: Longitudinal investigation of depression outcomes in primary care in six countries: the LIDO Study: functional status, health service use, and treatment of people with depressive symptoms. Psychol Med 2002; 32:889–902Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Radloff LS: The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. J Applied Psychol Measurement 1977; 1:385–401Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S: SF-12: How to score the SF-12 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales, 2nd ed. Boston, New England Medical Center, Health Institute, 1995Google Scholar

26. Mulrow C, Williams J, Gerrity M, Ramirez B, Montiel O: Case-finding instruments for depression in primary care settings. Ann Intern Med 1995; 122:913–921Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, Helzer JE, Babor TF, Burke J, Farmer A, Jablenski A, Pickens R, Regier DA, Sartorius N, Towle LH: The Composite International Diagnostic Interview: an epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:1069–1077Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Derogatis L, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L: The Hopkins Symptom Checklist: a measure of primary symptom dimensions, in Psychological Measurements in Psychopharmacology: Modern Problems in Pharmacopsychiatry, vol 7. Edited by Pichot P, Olivier-Martin R. Basel, Switzerland, S Karger, 1974, pp 79–110Google Scholar

29. Babor T, delaFuente J, Saunders J, Grant M: AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1989Google Scholar

30. Chisholm D, Knapp M, Knudsen H, Ammadeo F, Gaite L, Van Wijngaarden B (Epsilon Group): The Client Socio-Demographic and Service Receipt Inventory (CSSRI-EU): development of an instrument for international research. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176(suppl 39):S28-S33Google Scholar

31. Depression Guideline Panel: Depression in Primary Care, vol 2: Treatment of Major Depression: Clinical Practice Guideline Number 5: AHCPR Publication 93–0550. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Health Policy and Research, 1993Google Scholar

32. Mynors-Wallis L, Gath DH, Lloyd-Thomas AR, Tomlinson D: Randomised controlled trial comparing problem solving treatment with amitriptyline and placebo for major depression in primary care. BMJ 1995; 310:441–445Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Katon W, Robinson P, VonKorff M, Lin E, Bush T, Ludman E, Simon G, Walker E: A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:924–932Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Harlow S, Linet MS: Agreement between questionnaire data and medical records: the evidence for accuracy of recall. Am J Epidemiol 1989; 129:233–248Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Sturm R: Instrumental variable methods for effectiveness research. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 1999; 7:17–26Crossref, Google Scholar

36. Callahan CM, Hendrie HC, Dittus RS, Brater DC, Hui SL, Tierney WM: Improving treatment of late life depression in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994; 42:839–846Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Dowrick C, Buchan I: Twelve month outcome of depression in general practice: does detection or disclosure make a difference? BMJ 1995; 311:1274–1277Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Whooley M, Stone B, Soghikian K: Randomized trial of case-finding for depression in elderly primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med 2000; 15:293–300Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Wells KB, Katon W, Rogers B, Camp P: Use of minor tranquilizers and antidepressant medications by depressed outpatients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:694–700Link, Google Scholar

40. Simon G, VonKorff M, Piccinelli M, Fullerton C, Ormel J: An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. N Engl J Med 1999; 341:1329–1335Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar