Psychiatric Disorders Among Offspring of Depressed Mothers: Associations With Paternal Psychopathology

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The association between maternal depression and offspring dysfunction is well documented; however, little attention has been paid to psychopathology in the partners of these depressed mothers or to how paternal psychopathology might influence the relationship between maternal depression and offspring dysfunction. The purpose of this study was to explore whether major depression and/or antisocial behavior tended to occur more frequently among partners of depressed mothers (compared to partners of nondepressed mothers) and to examine how these paternal disorders related to offspring psychopathology. METHOD: Participants were drawn from the Minnesota Twin Family Study, a community-based study of twins and their parents. Depressed and nondepressed mothers, their partners (the biological fathers of the twins), and their 17-year-old offspring were included. Structured interviews were used to assess participants for the presence of major depression, conduct disorder, and adult antisocial behavior. RESULTS: Depressed mothers tended to partner with antisocial fathers. Depression in mothers and antisocial behavior in fathers were both significantly and independently associated with offspring depression and conduct disorder. No interactions of the parental diagnoses with each other or with the gender of the offspring were found. CONCLUSIONS: Many offspring of depressed mothers experience the additional risk of having an antisocial father. The implications of these findings for risk among the offspring of depressed mothers are discussed.

A substantial literature documents the association between maternal major depression and dysfunction in offspring. Problems among offspring of depressed mothers have been found in areas ranging from mental and motor development in infancy to social competence and psychopathology in adolescence (1). The disorders for which offspring of depressed mothers are at risk include two serious conditions—major depression and conduct disorder (e.g., reference 2)—that relate to problems in multiple domains of functioning (e.g., reference 3). Unfortunately, although assortative mating increases the likelihood that partners of depressed mothers will have some form of psychiatric disorder (4), relatively little attention has been paid to the fathers of these children and their possible contribution to the likelihood of their offspring’s developing major depression and/or conduct disorder.

There is support for the idea that fathers may play a role in the association between maternal major depression and offspring dysfunction. However, the influence of paternal major depression in the association between maternal major depression and offspring major depression remains unclear. Foley et al. (5) found that the risk of major depression in the offspring of depressed mothers was higher if the fathers were depressed as well, but Brennan et al. (6) reported that maternal major depression was related to major depression in offspring only in families in which the fathers were not depressed. Dierker et al. (7) reported a direct relationship between the number of parents affected by certain disorders and risk for those disorders in offspring; in fact, risk for conduct disorder among offspring was elevated only if both parents were affected by a psychological disorder. Similarly, Merikangas et al. (8) found higher rates of psychopathology among offspring of marital partners who were concordant for the presence of a psychiatric diagnosis, compared to couples in which only one partner had a psychiatric diagnosis. Conversely, the presence of a psychiatrically healthy father in the home was associated with lower rates of disorder among children of depressed mothers (9). In addition, among children of depressed mothers, the fathers’ psychiatric status and the parents’ marital relationship explained much of the variability in children’s social and emotional competence (10). In a study examining depressive symptoms, fathers’ scores on a measure of depression added to the prediction of emotional or behavioral problems in their children (as reported by teachers), beyond the variance accounted for by mothers’ depression scores (11).

These findings about assortative mating and how it relates to offspring psychopathology led Connell and Goodman (12) to recommend that researchers examine mental health in both spouses when studying links between parent and offspring psychopathology. Unfortunately, little is currently known about specific types of psychiatric illness among partners of depressed mothers; in addition, the potential association between different types of paternal psychopathology and risk to offspring is unclear. A clearer understanding of these relationships would clarify several important issues. First, knowledge of which psychiatric disorders tend to be present in partners of depressed women would aid our understanding both of people’s coupling practices and of the family makeup that children of depressed mothers experience. In addition, it could help clarify the reasons why children of depressed mothers are at risk for a diverse array of negative outcomes. As an extreme example, if all depressed women partnered with depressed men, then children of depressed mothers would, in actuality, be experiencing the effects of having two depressed parents. Eventually, a clearer understanding of these relationships could aid in the development of prevention and/or treatment programs for these youths. Studies that focus specifically on relationships between major depression and/or antisocial behavior among men who partner with depressed mothers likely would be particularly fruitful, since offspring of depressed mothers are at risk for both of these problems. Community-based studies would be especially valuable, since the findings would apply to the general population of depressed mothers and their children and would not be limited to those seeking treatment.

Thus, the first goal of this study was to examine whether, in a population-based sample, major depression and/or antisocial behavior tended to occur more frequently among the partners of depressed (versus nondepressed) mothers. Major depression was selected for investigation because of the possibility that depressed mothers engaged in “simple” assortative mating (mating with someone with their same disorder), combined with the fact that offspring of depressed mothers are at risk for major depression. Antisocial behavior was selected because offspring of depressed mothers are at risk for conduct disorder, and therefore it seemed particularly important to examine the potential presence of antisocial behavior among men who partner with depressed mothers (4). It was expected that partners of depressed mothers would have higher than normal rates of both major depression and antisocial behavior (due to both assortative mating and the association between maternal major depression and offspring antisocial behavior). The second goal of this study was to examine how this/these paternal disorder(s) related to offspring psychopathology. It was expected that this/these associated paternal disorder(s) would mediate the relationship between maternal major depression and offspring psychopathology. Specifically, the relationship between maternal major depression and offspring major depression and conduct disorder was expected to be weaker when paternal disorder(s) associated with maternal major depression (selected based on the results of analyses addressing the first goal) were also taken into account. Gender was also considered as a potential moderating variable in these relationships. Although gender differences in the base rates of major depression and conduct disorder were expected, gender differences in the relationships between parental disorders and offspring major depression and conduct disorder were not expected.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from the Minnesota Twin Family Study, an epidemiological study of twins and their parents. The Minnesota Twin Family Study uses public records to identify all twins born during specified birth years in the state of Minnesota and has a participation rate of 83.3%. There were no significant occupational differences between the parents of families that participated and those of families that declined participation. For this study, depressed and nondepressed mothers, their partners (the biological fathers of the twins), and their 17-year-old offspring were included. The 17-year-olds and their parents gave written informed consent or assent as appropriate. Each family member was interviewed by a different interviewer with no knowledge of other family members. Details about the design of the Minnesota Twin Family Study can be found elsewhere (13).

Affected mothers were selected if they had a lifetime diagnosis of major depression at either the definite level (meeting all DSM-III-R criteria for the disorder) or probable level (meeting all but one criterion). Nonaffected mothers had no probable or definite episode of major depression at any point in their lifetimes. To assess major depression, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (14) was administered. Interviewers had a bachelor’s or master’s degree in psychology or a related field and were extensively trained in diagnostic interviewing. Teams of advanced clinical psychology doctoral students determined the presence or absence of each symptom on the basis of written notes and audiotapes of the interviews. Only mothers from families for which data were also available on the biological father of the twins were included in the first part of the study, which examined characteristics of the partners of depressed mothers (N=552 [163 affected mothers and 389 nonaffected mothers], 88% of the mothers initially assessed). In the second part of the study, which examined offspring psychopathology, all available data were used (from 626 mothers and 556 fathers).

Consistent with the demographic makeup of the state of Minnesota at the time the twins were born, 99.1% (N=620) of the mothers in this study were Caucasian; there were no differences on this variable based on the depression status of the mother (χ2=3.63, df=4, p>0.05). There were no differences between depressed and nondepressed mothers on measures of occupational status (assessed by the Hollingshead Four-Factor Index of Social Status [15]) (t=1.17, df=496, p>0.05), maternal age (mean=44.4, SD=4.6) (t=1.03, df=550, p>0.05), or maternal years of education (mean=13.7, SD=1.9) (t=0.25, df=550, p>0.05). All mothers in this study reared their children; among families with both maternal and paternal data, 85% (N=469) of the fathers were full-time rearing fathers. Seventy-six percent (N=124) of the fathers who had partnered with depressed mothers, compared to 89% (N=345) of fathers who had partnered with nondepressed mothers, were rearing fathers (χ2=15.61, df=1, p<0.05).

Measures

Major depression diagnoses

The SCID (14) was administered to fathers and adolescents to assess lifetime definite or probable major depression. The parents’ version of the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents—Revised (16) was used to assess maternal reports of the adolescents’ major depression. If either the adolescent or the mother reported that the adolescent had experienced an episode that met these criteria, the adolescent was considered to have major depression. Kappa reliabilities for these diagnoses were adequate (major depression assessed with the SCID: kappa=0.89; major depression assessed with the parents’ version of the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents—Revised: kappa=0.91).

Antisocial behavior diagnoses

Symptoms of conduct disorder in mothers, fathers, and adolescents were assessed with an interview adapted directly from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II) (17). The parents’ version of the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents—Revised (16) was used for maternal reports of adolescents’ conduct disorder. Criterion C symptoms of antisocial personality disorder, or adult antisocial behavior, were assessed by directly interviewing the parents. Conduct disorder and/or adult antisocial behavior were considered present if the diagnostic criteria were met at a definite or probable level at any point in a participant’s lifetime. If either the mother or the adolescent reported that the adolescent had met the criteria for conduct disorder, the adolescent was considered to have conduct disorder. The DSM-III-R criteria for conduct disorder are quite similar to those in the DSM-IV, but DSM-IV requires clinically significant impairment and includes stricter wording for a few symptoms (e.g., “has deliberately engaged in fire-setting” in DSM-III-R was changed to “has deliberately engaged in fire setting with the intention of causing serious damage” in DSM-IV). Parents were considered to evidence antisocial behavior if they met the criteria for conduct disorder, adult antisocial behavior, or both. Kappa reliabilities for these diagnoses were adequate (conduct disorder assessed with the interview adapted from the SCID-II: kappa=0.85; conduct disorder assessed with the parents’ version of the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents—Revised: kappa=0.75; adult antisocial behavior assessed with the interview adapted from the SCID-II: kappa=0.95).

Statistical Analyses

First, chi-square analyses were conducted to determine whether maternal major depression was associated with 1) paternal major depression and 2) paternal antisocial behavior.

We then conducted logit analyses (suitable for examining associations among categorical independent and dependent variables) to examine relationships among parental and offspring diagnoses. The first step assessed gender differences in the odds of a diagnosis of conduct disorder or major depression in offspring. The second step added maternal major depression as a predictor to determine whether it was associated with offspring major depression or conduct disorder, independent of any gender effects (thus replicating previous findings). The third step assessed whether any paternal diagnoses associated with maternal major depression (either paternal major depression or antisocial behavior) might similarly be associated with offspring major depression or conduct disorder. In the final step, any significant associations obtained in step three were followed up by adding maternal major depression as an additional predictor. If paternal disorder(s) mediated any association between maternal major depression and offspring major depression or conduct disorder, then this association (between maternal major depression and offspring major depression or conduct disorder) should become nonsignificant when it was adjusted for the effects of the paternal disorder. All analyses included offspring gender as a predictor; effects of parental diagnoses were thus adjusted for gender differences in risk for the two offspring disorders. Potential interactions between gender and parental disorders were also assessed. Only significant interactions were retained in the final models. Odds ratios, obtained by exponentiating regression parameters associated with predictor variables, indicate the odds of a particular outcome for one group (e.g., offspring of a depressed mother) relative to that of another group (e.g., offspring of a nondepressed mother).

To accommodate the fact that the study group consisted of twins from the same family, the method of generalized estimating equations (18) was used in the logit analyses. To the degree that twins resembled each other for major depression or conduct disorder, standard logit analyses would overestimate the precision of parameter estimates by underestimating standard errors. Generalized estimating equations, which were developed specifically to accommodate correlated data such as those used in this study (18), were used to simultaneously estimate the correlation between twins as well as the regression parameters relating independent and dependent variables, thus producing more appropriate estimates of standard errors. Generalized estimating equations are especially suitable when the correlation between twins is considered primarily a “nuisance” factor, rather than a main object of study, as was the case in this study.

Results

Paternal Psychiatric Disorders Associated With Maternal Major Depression

Results of chi-square analyses indicated that the partners of depressed mothers had elevated rates of antisocial behavior; 37% (N=143) of the partners of nondepressed mothers had antisocial behavior, compared to 49% (N=80) of the partners of depressed mothers (χ2=7.24, df=1, p<0.01). It should be noted that these relatively high rates of antisocial behavior among the fathers were expected, given the relatively broad inclusion criteria (probable or definite lifetime diagnoses of conduct disorder or adult antisocial behavior). Maternal major depression was not associated with paternal major depression; 13% (N=51) of the partners of nondepressed mothers had major depression, compared to 15% (N=24) of the partners of depressed mothers (χ2=0.26, df=1, p>0.05). Thus, mothers with histories of major depression tended to partner with men who had histories of antisocial behavior.

One explanation for this finding could have been that the mothers with major depression also tended to have antisocial behavior and that their partnering with antisocial men could be explained by this similarity (as would be supported by the findings of Krueger et al. [19] that people mate assortatively for antisocial behavior specifically). To investigate this possibility, we first examined whether maternal antisocial behavior was associated with paternal antisocial behavior and found that it was; 39% (N=198 of 510) of the partners of mothers with no antisocial behavior had antisocial behavior, compared to 60% (N=25 of 42) of the partners of mothers with antisocial behavior (χ2=6.91, df=1, p<0.01). To ensure that this result did not account for the finding that depressed mothers tended to partner with fathers with antisocial behavior, the mothers who had antisocial behavior were eliminated from the analysis and the association between maternal major depression and paternal antisocial behavior was reexamined. The association between maternal major depression and paternal antisocial behavior remained significant; in this subgroup, 35% (N=127 of 359) of the partners of nondepressed mothers had antisocial behavior, compared to 47% (N=71 of 151) of the partners of depressed mothers (χ2=6.07, df=1, p<0.01), indicating that this finding was not an artifact of simple assortative mating for antisocial behavior specifically. In addition, the finding (reported above) that maternal major depression was not significantly associated with paternal major depression indicated that this finding was not an artifact of simple assortative mating for major depression. Therefore, the finding that mothers with major depression tend to partner with fathers with antisocial behavior cannot be explained by specific assortative mating for each disorder combined with the tendency for these disorders to co-occur within individuals.

Relationship Between Parental Diagnoses and Risk for Psychopathology in Offspring

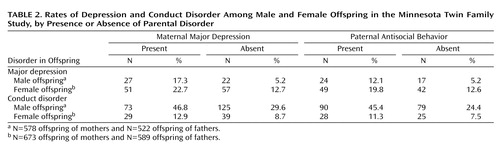

As expected, there were gender differences in the prevalence of major depression and conduct disorder among offspring (major depression in male offspring: 8% [N=49 of 578]; major depression in female offspring: 16% [N=108 of 674]; conduct disorder in male offspring: 34% [N=198 of 578]; conduct disorder in female offspring: 10% [N=68 of 674]). Logit analyses using generalized estimating equations confirmed that these gender differences were significant (Table 1).

Although effects of parental diagnoses were frequently greater in magnitude for male than female offspring (Table 2), none of the interactions between parental diagnosis and offspring gender were significant in the logit analyses (the absolute value of all chi-square statistics was less than 2.90; all associated p>0.08). Table 1 therefore presents common odds ratios for effects of parental diagnoses on offspring disorders for male and female offspring combined. Because offspring sex was included in the model, odds ratios for parental diagnoses are adjusted for gender differences in the odds of each disorder. The first set of logit analyses, with maternal major depression as the independent variable and offspring major depression or conduct disorder, respectively, as dependent variables, indicated that a maternal diagnosis of major depression was associated with both offspring major depression and offspring conduct disorder. Because maternal major depression was associated with antisocial behavior, but not major depression, in the fathers, we next assessed whether paternal antisocial behavior was associated with major depression and conduct disorder in the offspring. Both associations were significant. This finding raised the possibility that paternal antisocial behavior might mediate the associations between maternal major depression and offspring disorders. We therefore included both maternal major depression and paternal antisocial behavior as predictors, with either offspring major depression or offspring conduct disorder as the dependent variables, in the next set of logit analyses. The effect of each parental diagnosis remained significant when each finding was adjusted for effects of the other. The interaction between paternal antisocial behavior and maternal major depression was not significant for offspring major depression or conduct disorder (χ2=2.59, df=1, p=0.11, and χ2=0.90, df=1, p=0.34, respectively). Paternal antisocial behavior and maternal major depression thus had significant independent effects on offspring major depression and offspring conduct disorder.

Discussion

The results of this study indicated that maternal major depression and paternal antisocial behavior are both significantly and independently associated with both offspring major depression and offspring conduct disorder. No interaction of these parental disorders was found; the effect of one did not moderate the effect of the other. Thus, a youth with either a depressed mother or an antisocial father is at risk for both major depression and conduct disorder and also has an increased likelihood of having the other parent evidence these forms of psychopathology—resulting in risk from both parents. These results are thus consistent with other studies indicating that psychopathology in a child’s second parent increases risk among offspring (4, 5, 7) and extend this line of study by showing in particular the importance of paternal antisocial behavior. In addition, major depression in mothers and antisocial behavior in fathers appear to be specifically related to major depression and conduct disorder in offspring—more so than antisocial behavior in mothers or major depression in fathers (20). Thus, when fathers are not included in studies that examine offspring of depressed mothers, the results may be conflating the risk associated with having a depressed mother and the risk associated with having an antisocial father.

The mechanisms by which this risk to offspring is transmitted are not clear, but they likely include both genetic and environmental components. Both major depression and conduct disorder are influenced by genetic factors (e.g., references 21, 22). In addition, family risk factors (such as divorce, poor parental marital adjustment, and parent-child discord) are more common in families of depressed parents, compared to families in which the parents do not have major depression (23). Parents with antisocial behavior are also more likely to divorce (or have children without being married) than parents without antisocial behavior (24). Recent intergenerational research suggests that financial problems and parenting styles mediate the intergenerational continuity of antisocial behavior, with fathers’ adolescent delinquency and mothers’ parenting styles playing especially strong roles in predicting offspring antisocial behavior (25). Chronic family stress and expressed emotion in fathers may mediate the relationship between parental psychopathology and offspring major depression (6). Thus, it appears likely that both genetic and environmental factors, and quite possibly the interaction of these influences, affect the relationships found in this study between maternal major depression and offspring major depression and between paternal antisocial behavior and offspring conduct disorder. However, the potential reasons for the links between maternal major depression and offspring conduct disorder and between paternal antisocial behavior and offspring major depression are less clear. A more general genetic risk (not specific to a particular disorder, but relating to more general factors such as difficulties coping with stressful situations or social problems) may affect this type of transmission; in addition, the family risks that are common among families with a parent with major depression or antisocial behavior likely also act as risk factors for other disorders. These links may also be explained by more specific aspects of the parenting of mothers and fathers with these disorders; for example, mothers with major depression may be withdrawn and lethargic and therefore not monitor their children adequately, thereby placing them at risk for conduct disorder, while fathers with antisocial behavior may encounter trouble with the law, which could make their children upset or embarrassed, thereby placing them at risk for major depression.

The relationships found between parental and offspring disorders did not differ according to whether the offspring was male or female. Thus, the results of this study support the notion that associations between parental disorders and offspring disorders do not differ by gender, despite gender differences in the base rates of major depression and conduct disorder.

The results of this study also indicated that mothers with a history of major depression tend to partner with men who have a history of antisocial behavior. This association remains even when mothers who have a history of antisocial behavior in addition to their major depression are removed from the analysis, indicating that the pattern of depressed mothers’ partnering with antisocial fathers is not due to simple assortative mating for antisocial behavior. Conversely, no association was found between maternal major depression and paternal major depression, indicating that mothers with a history of major depression are no more likely to partner with depressed men than are their nondepressed counterparts.

The lack of an increased prevalence of major depression among partners of depressed mothers, compared to partners of nondepressed mothers, contradicts the findings of Brennan et al. (6), who reported that spouses of depressed mothers were at increased risk for major depression. This difference may relate to the inclusion criteria for the two studies (26). In the present study, all mothers with a history of probable or definite DSM-III-R major depression (based on a structured interview) for whom data were also available on biological fathers were included. In the Brennan et al. study, mothers first completed a self-report depression inventory and were considered for inclusion if they rated themselves as having moderate or severe depression at two or more time points (ranging from before the birth of the target child until the child was age 15 years), severe depression one time between the time they were pregnant and their child was age 5 years, or low-level depression at all time points. Then, they completed a structured interview assessing DSM-IV symptoms of major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder. Because of these inclusion requirements, the participants in the study by Brennan et al. may have included primarily women with recurring depressive disorders—perhaps a more severely ill group than the women included in the present study. Brennan et al. specified that their study group was considered “high-risk,” while our sample was considered representative of the population.

It is not clear why this particular combination of parental disorders (depressed mothers and antisocial fathers) emerged as a common pattern. That is, one might expect to find simple assortative mating for antisocial behavior (as has been demonstrated by Krueger et al. [19]) and major depression (as was found by Brennan et al. [6]) separately. However, Dierker et al. (7) did report differing concordance rates between spouses for different types of psychopathology; perhaps people with certain types of psychopathology tend to seek out people with psychological problems different from their own. Specifically, in this case, women who are depressed (and perhaps withdrawn or hopeless) may seek out men who appear strong and self-confident. Conversely, antisocial men may seek out women who are depressed and perhaps meek so that they can dominate and control them. It is important to remember, however, that this study measured lifetime diagnoses and therefore the temporal relationship among the disorders in mothers and fathers and the partnering of the two parents is unknown. Thus, it is possible that, for example, antisocial men partnered with women who were not initially depressed but that some women developed major depression as a result of distress over their partner’s antisocial behavior.

This study had several strengths. The selection of participants was community-based and therefore not biased toward people who sought treatment. We included families in which the biological parents had raised the children together until at least age 17 years as well as families in which the biological father had much less involvement with the children but still participated in the study. Thus, the results are not biased toward families that remained intact. In addition, through the use of statistical techniques that accommodated the fact that two offspring from each family were included, we were able to include diagnostic information on two offspring from each participating family. Although the inclusion of twins could be seen as reducing the generalizability of findings, previous research indicated that psychopathology among twins does not differ from psychopathology among nontwins (27).

Several limitations of this study should also be noted. Participants were primarily Caucasian (99%), representing the demographic makeup of Minnesota at the time the twins were born. Participants were required to report on past behaviors; thus, as with all retrospective studies, these reports may have been subject to memory biases. In addition, somewhat fewer fathers in families with a depressed mother were full-time rearing fathers (compared to families with a nondepressed mother); it is possible that the results relating to offspring diagnoses would differ between families in which the biological father also reared the children and families in which the biological father was not a full-time rearing father. Thus, additional research addressing the relationships among parental psychopathology, family structure, and offspring psychopathology would be useful.

|

|

Presented in part at a meeting of the International Society for Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, Sydney, Australia, June 25–29, 2003. Received Aug. 14, 2003; revision received Nov. 4, 2003; accepted Nov. 7, 2003. From the Department of Psychology, Rutgers University, Camden, N.J.; and the Department of Psychology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Address reprint requests to Dr. Marmorstein, Department of Psychology, Rutgers University, 311 N. 5th St., Camden, NJ 08102; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grant DA-05147 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and grant AA-09367 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

1. Gotlib IH, Goodman SH: Children of parents with depression, in Developmental Issues in the Clinical Treatment of Children. Edited by Silverman WK, Ollendick TH. Boston, Allyn & Bacon, 1999, pp 415–432Google Scholar

2. Boyle MH, Pickles AR: Influence of maternal depressive symptoms on ratings of childhood behavior. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1997; 25:399–412Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Marmorstein NR, Iacono WG: Major depression and conduct disorder in a twin sample: gender, functioning, and risk for future psychopathology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42:225–233Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Merikangas KR, Prusoff BA, Weissman MM: Parental concordance for affective disorders: psychopathology in offspring. J Affect Disord 1988; 15:279–290Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Foley DL, Pickles A, Simonoff E, Maes HH, Silberg JL, Hewitt JK, Eaves LJ: Parental concordance and comorbidity for psychiatric disorder and associate risks for current psychiatric symptoms and disorders in a community sample of juvenile twins. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2001; 42:381–394Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Brennan PA, Hammen C, Katz AR, Le Brocque RM: Maternal depression, paternal psychopathology, and adolescent diagnostic outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol 2002; 70:1075–1085Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Dierker LC, Merikangas KR, Szatmari P: Influence of parental concordance for psychiatric disorders on psychopathology in offspring. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:280–288Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Merikangas KR, Weissman MM, Prusoff BA, John K: Assortative mating and affective disorders: psychopathology in offspring. Psychiatry 1988; 51:48–57Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Conrad M, Hammen C: Role of maternal depression in perceptions of child maladjustment. J Consult Clin Psychol 1989; 57:663–667Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Goodman SH, Brogan D, Lynch ME, Fielding B: Social and emotional competence in children of depressed mothers. Child Dev 1993; 64:516–531Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Thomas AM, Forehand R: The relationship between paternal depressive mood and early adolescent functioning. J Fam Psychol 1991; 4:260–271Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Connell AM, Goodman SH: The association between psychopathology in fathers versus mothers and children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2002; 128:746–773Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor J, Elkins IJ, McGue M: Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance use disorders: findings from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Dev Psychopathol 1999; 11:869–900Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1987Google Scholar

15. Hollingshead AB: Four-Factor Index of Social Status. New Haven, Conn, Yale University, Department of Sociology, 1975Google Scholar

16. Reich W, Welner Z: Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents—Revised: DSM-III-R Version. St. Louis, Washington University, 1988Google Scholar

17. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1987Google Scholar

18. Liang KY, Zeger SL: Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 1986; 73:13–22Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Krueger RF, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Bleske A, Silva P: Assortative mating for antisocial behavior: developmental and methodological implications. Behav Genet 1998; 28:173–186Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Marmorstein NR, Iacono WG: Major depression and conduct disorder in youth: associations with parental psychopathology and parent-child conflict. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2004; 45:377–386Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Slutske WS, Heath AC, Dinwiddie SH, Madden PAF, Bucholz KK, Dunne MP, Statham DJ, Martin NG: Modeling genetic and environmental influences in the etiology of conduct disorder: a study of 2,682 adult twin pairs. J Abnorm Psychol 1997; 106:266–279Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Thapar A, McGuffin P: A twin study of depressive symptoms in childhood. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 165:259–265Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Fendrich M, Warner V, Weissman M: Family risk factors, parental depression, and psychopathology in offspring. Dev Psychol 1990; 26:40–50Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Emery RE, Waldron M, Kitzmann KM, Aaron J: Delinquent behavior, future divorce or nonmarital childbearing, and externalizing behavior among offspring: a 14-year prospective study. J Fam Psychol 1999; 13:568–579Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Thornberry TP, Freeman-Gallant A, Lizotte AJ, Krohn MD, Smith CA: Linked lives: the intergenerational transmission of antisocial behavior. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2003; 31:171–184Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Hammen C, Brennan PA: Depressed adolescents of depressed and nondepressed mothers: tests of an interpersonal impairment hypotheses. J Consult Clin Psychol 2001; 69:284–294Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Kendler KS, Martin NG, Heath AC, Eaves LJ: Self-report psychiatric symptoms in twins and their non-twin relatives: are twins different? Am J Med Genet 1995; 60:588–591Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar