Refining Personality Disorder Diagnosis: Integrating Science and Practice

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Personality disorder researchers are currently evaluating a range of potential solutions to problems with the DSM-IV diagnostic categories. This article proposes changes to the diagnostic categories and criteria based on empirical findings from a national sample of patients with personality disorder diagnoses. METHOD: The Shedler-Westen Assessment Procedure (SWAP-200) is a personality assessment tool designed to capture the richness and complexity of clinical personality descriptions while providing reliable and quantifiable data. A national sample of experienced psychiatrists and psychologists used the SWAP-200 to describe either their conceptions (prototypes) of personality disorders (N=267) or current patients with personality disorder diagnoses (N=530). RESULTS: Clinicians" conceptions of personality disorders and their descriptions of actual patients overlapped with the DSM descriptions but also differed in systematic ways. Their descriptions were clinically richer than the DSM descriptions and placed greater emphasis on patients" mental life or inner experience. The study identifies potential diagnostic criteria that may be more defining of personality syndromes than some of the current DSM criteria. CONCLUSIONS: Diagnostic criterion sets should be expanded to better address the multiple domains of functioning inherent in the concept of personality and should more explicitly address patients’ mental life or inner experience. The authors offer recommendations for revision of the diagnostic categories and criteria and also propose a prototype matching approach to personality disorder diagnosis that may overcome limitations inherent in the current diagnostic system.

A clinically useful and empirically sound classification of personality disorders has been an elusive ideal. A clinically useful diagnostic system should encompass the spectrum of personality pathology seen in clinical practice and have meaningful implications for treatment. An empirically sound diagnostic system should facilitate reliable and valid diagnoses: independent clinicians should be able to arrive at the same diagnosis, the diagnoses should be relatively distinct from one another, and each diagnosis should be associated with unique and theoretically meaningful correlates, antecedents, and sequelae (1–3).

Personality disorder researchers are coming to a consensus about a range of problems with the current axis II diagnostic system. Here we briefly review some of the major concerns (see also references 1, 4–11).

Why Revise Axis II?

Excessive comorbidity between personality disorders has been a persistent problem since DSM-III. Patients who receive any personality disorder diagnosis typically receive several (12–16). In attempting to sharpen the boundaries between personality disorders, DSM task forces have gerrymandered diagnostic categories and criteria, sometimes in ways faithful neither to clinical observation nor empirical data (e.g., excluding lack of empathy and grandiosity from the diagnostic criteria for antisocial personality disorder to minimize comorbidity with narcissistic personality disorder—despite evidence that these traits are strongly associated with antisocial personality disorder [17]). Efforts to define personality disorders more precisely have also led to narrower criterion sets over time, progressively eroding the distinction between personality disorders (multifaceted syndromes encompassing cognition, affectivity, motivation, interpersonal functioning, and so on) and simple personality traits (single dimensions, such as dependency). For example, the diagnostic criteria for paranoid personality disorder are essentially redundant indicators of one trait, chronic suspiciousness. The diagnostic criteria no longer describe the multifaceted personality syndrome recognized by most clinical practitioners or encompass the multiple domains of psychological functioning described in the preamble to axis II (18, 19).

Many investigators have noted that a categorical system (in which disorders are judged present/absent) may not be optimal for diagnosing personality disorders (20–22). Personality pathology may be better conceptualized dimensionally, e.g., on a continuum from mild through moderate to severe. The same concern applies to individual diagnostic criteria, most of which are continuously distributed in nature (23).

The current algorithm for diagnostic decisions—counting symptoms—imposes thresholds that may be arbitrary and unreliable (12, 21) and diverges from the methods clinicians use (or could plausibly be expected to use) in real-world practice. Research in cognitive science suggests that clinicians do not diagnose personality disorders by additively tabulating symptoms. Rather, they gauge the match between a patient and the features of a personality syndrome taken as a configuration or gestalt, or they use causal theories that make sense of constellations of symptoms (24–27). Finally, axis II does not encompass the spectrum of personality pathology that clinicians actually see in practice (28).

Overview and Goals

Research aimed at refining personality disorder diagnostic criteria is often constrained by the use of assessment instruments designed to assess existing DSM categories and criteria, including at most a limited number of additional items in field trials. Such assessment instruments implicitly presume the basic accuracy of the taxonomy they are intended to evaluate and therefore can lead only to minor adjustments. Developing, refining, or testing the comprehensiveness of a classification system necessarily requires larger and more diverse item sets than classifying cases using an existing taxonomy (29, 30).

This study attempts to identify the central features of the personality disorders included in DSM-IV as they are 1) conceptualized by practicing clinicians and 2) observed empirically in patients treated in the community. A national sample of experienced psychologists and psychiatrists used the Shedler-Westen Assessment Procedure (SWAP-200) (8, 9, 31) either to describe their mental prototype of an axis II personality disorder (i.e., a hypothetical, prototypical patient who illustrates a personality disorder in its ideal or pure form) or to provide a detailed psychological portrait of a current patient with a specific personality disorder diagnosis. The SWAP-200 is a personality assessment instrument designed to capture the richness and complexity of clinical personality observations while providing reliable and quantifiable data.

This study asks the following questions: 1) Do clinicians in the community conceptualize personality disorders in ways that differ from the DSM-IV descriptions? If so, do they nevertheless share a common, consensual understanding? 2) Empirically, which personality features best describe patients with personality disorders treated in the community?

Method

The data collection methods and sample characteristics have been described in detail previously (8); here we summarize those aspects relevant to the present report.

Clinician-Consultants

A national sample of 797 experienced psychiatrists and clinical psychologists recruited from the rosters of the American Psychiatric Association and the American Psychological Association contributed data to the study. Each clinician-consultant used the SWAP-200 to provide a detailed psychological portrait of a single patient, either actual or hypothetical. The clinician-consultants had an average of 18.1 years practice experience posttraining. Approximately one-third were psychiatrists and two-thirds were psychologists. Thirty-one percent worked in hospitals at least part time, 20% worked in clinics, 82% maintained private practices, and 11% worked in forensic settings. The clinician-consultants described their primary theoretical orientation as psychodynamic (48.6%), eclectic (29.4%), cognitive behavioral (14.4%), biological (4.8%), and systemic (2.0%).

The SWAP-200: Quantifying Clinical Observation

The SWAP-200 is a set of 200 personality-descriptive statements or items, each printed on a separate index card. To describe a patient, a clinician sorts the statements into eight categories, from those that are least descriptive of the patient (assigned a value of 0) to those that are most descriptive (assigned a value of 7). Thus, the procedure yields a numeric score from 0 to 7 for each of 200 personality-descriptive statements. An interactive, Web-based version of the instrument is also available and may be previewed at www.psychsystems.net/guest.cfm. The SWAP-200 is based on the Q-sort method, which requires clinicians to arrange the items into a prespecified or “fixed” distribution. This method is designed to maximize reliability and minimize error variance (32). The SWAP-200 distribution approximates the right half of a normal distribution, with half (N=100) of the items placed in the “0” or least descriptive category, and progressively fewer items placed in the higher categories. Eight items are placed in the “7” or most descriptive category.

The SWAP-200 item set subsumes axis II criteria included in DSM-III through DSM-IV. Additionally, it incorporates selected axis I criteria relevant to personality (e.g., anxiety and depression), important personality constructs described in the clinical and research literatures over the past 50 years, and clinical observations from multiple pilot studies. Most important, the SWAP-200 is the product of a 7-year iterative revision process that incorporated the feedback of hundreds of clinician-consultants who used earlier versions of the instrument to describe their patients. We asked each clinician-consultant one crucial question: “Were you able to describe the things you consider psychologically important about your patient?” We added, rewrote, and revised items based on this feedback, then asked new clinician-consultants to describe new patients. We repeated this process over many iterations until most clinicians could answer “yes” most of the time.

The SWAP-200 has shown strong evidence of validity in prior studies (8, 33, 34). Overall reliability of a SWAP-200 personality description based on two raters has ranged from 0.75 to 0.81 (Spearman-Brown formula) (31). (A SWAP-200 description or profile consists of one column by 200 rows of data, with each row containing the score for the corresponding SWAP-200 item. If two clinicians describe the same patient, the interrater reliability of the overall personality profile is obtained by correlating the two columns.)

Identifying Core Features of Personality

SWAP-200 personality descriptions can be averaged or aggregated across multiple patients to derive a composite personality description for a particular diagnostic grouping (e.g., a composite description of either actual patients diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder or clinicians’ hypothetical prototypes of patients with narcissistic personality disorder). An important psychometric benefit of aggregation is that the idiosyncrasies of individual patients and clinicians (i.e., error variance) tend to cancel out in adequately sized samples (35, 36). Thus, an aggregate or composite description of patients with a given personality disorder reveals the core psychological features shared by the patients. Similarly, a composite description of hypothetical, prototypical patients illustrating a given personality disorder reflects the core consensual understanding of the personality disorder shared by clinicians in the community, based on commonalities of observation, experience, and training.

The reliability of an aggregate personality description is measured by coefficient alpha, which reflects the intercorrelations between the patients (columns of data) included in the composite. The logic is identical to computing the reliability of a psychometric scale, except that patients are treated as scale “items” (columns in the data file) and SWAP-200 items are treated as cases (rows in the data file). This method has a well-established history in Q-sort research (32, 37–39).

Procedures

We initially surveyed the clinician-consultants to determine which personality disorder diagnoses were represented in their practices. On the basis of their responses, we asked two-thirds (N=530) to use the SWAP-200 to describe a current patient who met DSM-IV criteria for a specific personality disorder. To obtain data on clinicians’ conceptions or prototypes of personality disorders, we asked one-third (N=267) to use the SWAP-200 to describe a hypothetical, prototypical patient who illustrated a specified personality disorder “in its purest form.” Clinician-consultants who described hypothetical, prototypical patients received the following instructions (here we use histrionic personality disorder as an example):

We are asking you to use the SWAP-200 to describe a hypothetical patient with histrionic personality disorder. We do not want you to describe a real patient. Rather, we are interested in learning what the term “histrionic personality disorder” connotes for you. We would like you to describe a prototypical histrionic patient, a hypothetical person who illustrates histrionic personality disorder in its purest form.

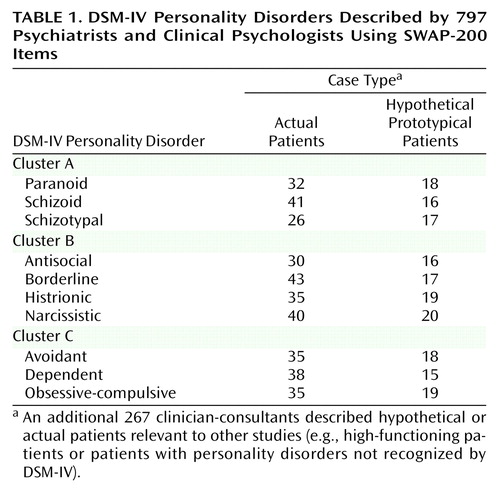

The number of actual and prototypical cases described by the clinician-consultants for each of the DSM-IV personality disorders is presented in Table 1.

Results

We use the term “clinical prototype” to refer to an aggregate personality disorder description based on hypothetical, prototypical patients. We use the term “composite description” to refer to an aggregate description based on actual patients diagnosed with a given personality disorder. Coefficient alpha was ≥0.90 for all of the clinical prototypes and composite descriptions described in this study, indicating that the sample sizes were adequate to obtain stable and reliable personality disorder descriptions. For ease of presentation, we report findings separately for each axis II cluster. Within each cluster, we first report clinicians’ conceptions or prototypes of personality disorders, followed by descriptions of actual patients.

Clinician Conceptions of Cluster A Personality Disorders—The “Odd” Cluster

Table 2 lists the SWAP-200 items that received the highest scores or rankings in each clinical prototype (i.e., aggregate description of hypothetical patients) for the cluster A personality disorders, along with the item’s mean score or ranking in the prototype (i.e., its centrality or importance in defining the personality disorder). Two findings are noteworthy. First, there is considerable overlap in item content between the three cluster A disorders. Thus, there are psychological features that clinicians regard as central to two or all three of the cluster A disorders, including lack of insight, difficulty making sense of other people’s behavior, a tendency toward social isolation, and odd or peculiar reasoning. If we consider each clinical prototype as a whole (that is, if we consider the “gist” or gestalt of the 15 to 20 most descriptive statements), the clinical prototypes are easily distinguishable. However, if we limit the descriptions to just the first eight to nine items—the number included in DSM-IV criterion sets—it is more difficult to distinguish them. This suggests that criterion sets of eight to nine items are too small to provide personality disorder descriptions that are both clinically accurate and adequately distinct (10).

Second, clinicians’ conceptions of the personality disorders differed systematically from the DSM-IV descriptions and included psychological features absent from the DSM criterion sets. Clinicians regard the defenses of externalization (“tends to blame others for own failures or shortcomings”) and projection (“tends to see own unacceptable feelings or impulses in other people instead of in him/herself”) as centrally defining features of paranoid personality disorder. The finding is striking given the diversity of theoretical orientations of the clinician-consultants. (When we reanalyzed the data excluding clinicians who reported a psychoanalytic or psychodynamic orientation, these two items actually received slightly higher rankings.)

The clinicians also emphasized paranoid patients’ anger and hostility, sense of victimization, lack of insight, and cognitive distortions in ways DSM-IV does not. In general, clinicians emphasized aspects of patients’ mental life (or inner experience) as well as overt behaviors, whereas the axis II criterion sets place more emphasis on behaviors.

Empirically Observable Features of Cluster A Personality Disorders

Table 3 lists the SWAP-200 items that received the highest scores or rankings in the composite descriptions of actual patients.

Paranoid personality disorder

Like the clinical prototype, the composite description of actual paranoid patients includes items addressing patients’ mental life that are absent from the DSM-IV criterion set. Externalization and projection are empirically observable processes in paranoid patients. Other empirically observable characteristics absent from DSM-IV include anger and hostility, feelings of victimization, difficulties understanding the actions of others, hypersensitivity to slights, lack of close friendships and relationships, and the tendency for reasoning to become severely impaired under stress.

Schizoid and schizotypal personality disorders

The composite description of patients with schizoid personality disorder (Table 3) differs from the DSM-IV description in important ways. Clinicians who know schizoid personality disorder patients well describe them as experiencing considerably more psychological pain than acknowledged by DSM-IV, which instead emphasizes flat affect. Empirically observable features of patients with schizoid personality disorder include not only social isolation and interpersonal peculiarity but also depression and despondency, interpersonal avoidance motivated by fear of embarrassment or humiliation, anxiety, feelings of inadequacy, and inhibitions about pursuing gratification.

The composite descriptions of patients diagnosed with schizoid and schizotypal personality disorders are highly correlated (r=0.83) and essentially empirically indistinguishable. Thus, the findings do not support a taxonomy in which schizoid and schizotypal personality disorders are independent diagnostic entities. The findings support a single combined diagnostic category, with diagnostic criteria including not only the more classically schizoid and schizotypal phenomena but also items addressing underlying depression, anxiety, sense of inadequacy, and fear of embarrassment and humiliation. (These findings are consistent with those of Walker and Lewine [40], who reported a prospective relationship between the trait of “negative affectivity” and subsequent development of thought disorder.)

Clinician Conceptions of Cluster B Personality Disorders—The “Dramatic” Cluster

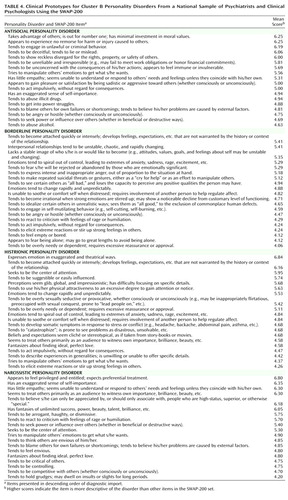

Table 4 lists the SWAP-200 items that received the highest ranking in the clinical prototypes of cluster B disorders. Three features are noteworthy. First, clinicians have clear and distinct conceptions of antisocial and narcissistic personality disorders, even while recognizing that the disorders share common features (e.g., lack of empathy, a tendency to externalize blame, a power-oriented approach to relationships, problems with hostility). As with the cluster A disorders, the clinical prototypes are readily distinguishable when the features are considered as a configuration or gestalt.

Second, clinicians’ consensual understanding of antisocial personality disorder encompasses many features of the construct of psychopathy that preceded the current antisocial personality disorder diagnosis (41, 42). The clinicians emphasized lack of concern with consequences, lack of empathy, and interpersonal manipulativeness. These findings are consistent with the ICD-9 description of dyssocial personality disorder, which also emphasizes callous lack of concern for others, incapacity to experience guilt, and externalization.

Third, clinicians do not have well-differentiated conceptions of borderline and histrionic personality disorder. Among the 18–20 most descriptive items for each disorder are numerous items common to both, including the tendency to become attached quickly and intensely, emotions that spiral out of control, difficulty regulating emotion without the involvement of another person, impulsivity, and dependency.

Empirically Observable Characteristics of Cluster B Personality Disorders

Antisocial personality disorder

The composite description of actual antisocial patients (Table 5), like the clinical prototype (and like some of the DSM-IV field trial data [43]), includes multiple traits associated with psychopathy. Included in the composite description, but absent from the DSM-IV criterion set, are items addressing externalization of blame, lack of empathy, lack of remorse, an apparent imperviousness to consequences, sadism, and a tendency to manipulate others’ emotions.

Borderline personality disorder

The composite description of actual patients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (Table 5) is strikingly different from the current DSM-IV description. It is interesting that the clinicians’ prototypes of borderline personality disorder resembled the DSM criteria more than they resembled the descriptions of actual patients. Actual borderline patients are most defined by emotional dysregulation and intense emotional pain or dysphoria. They also experience feelings of depression, inadequacy, helplessness, anxiety, rage, and victimization. Few of these features are currently diagnostic criteria for the disorder.

Neither psychotic symptoms nor dissociation appear among the 20 most empirically descriptive characteristics of borderline personality disorder, but a related criterion is highly descriptive—a tendency to become irrational when strong emotions are stirred up, with a noticeable decline from customary level of functioning. Stated differently, borderline patients appear to become disorganized under the pressure of intense affect, but they function at a higher level in periods of relative affective quiescence.

Histrionic personality disorder

The empirical portrait of actual histrionic patients (Table 5) further illustrates why research has so consistently found high comorbidity between borderline and histrionic personality disorders, and why clinicians also confuse the disorders. Patients diagnosed with these personality disorders share numerous features, including fears of rejection and abandonment, anxiety, dependency, a tendency to feel misunderstood, emotions that spiral out of control, difficulty self-soothing, and a tendency to catastrophize. The features that are uniquely defining of histrionic patients are theatrical expression of emotion, sexual seductiveness and provocativeness, and somatization (harkening back to historical descriptions of the hysterical character [44, 45]).

Narcissistic personality disorder

The composite description of actual narcissistic patients (Table 5), like the aggregate description of hypothetical, prototypical narcissistic patients, reveals a coherent syndrome that strongly resembles the DSM-IV description. However, it also includes features absent from DSM-IV, including the tendencies to be controlling and competitive, to get into power struggles, to feel misunderstood and mistreated, to externalize blame, and to hold oneself to unrealistic standards of perfection.

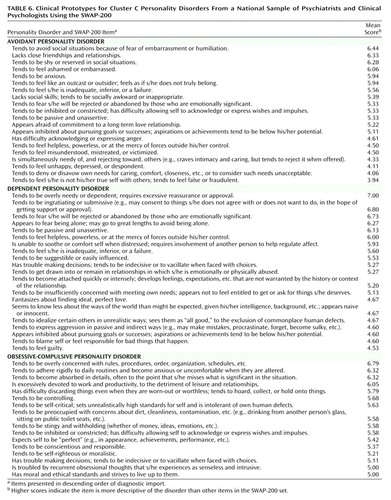

Clinician Conceptions of Cluster C Personality Disorders—The “Anxious” Cluster

Table 6 lists the SWAP-200 items that received the highest scores or rankings in the clinical prototypes. Clinicians’ prototypes of avoidant personality disorder resemble the DSM-IV version of the disorder, including the centrality of inhibition, shame, feelings of inadequacy and inferiority, and interpersonal reserve. However, the second most defining feature of the clinical prototype for avoidant personality disorder—lack of close friendships—was excluded from DSM-IV in an effort to minimize comorbidity with schizoid personality disorder.

The clinical prototype for dependent personality disorder (Table 6) also resembles the DSM-IV description but is less tied to a single trait—willingness to do almost anything to avoid being left alone (which was included in the DSM-IV description to minimize comorbidity with other personality disorders). Instead, the clinical prototype describes a clinically richer constellation of traits addressing ways of feeling (e.g., helpless, inadequate, guilty, fearful of being alone or abandoned), thinking (e.g., indecisive, naive), and behaving (e.g., needy, submissive, passive, etc.).

The clinical prototype for obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (Table 6) resembles the DSM-IV description of the disorder.

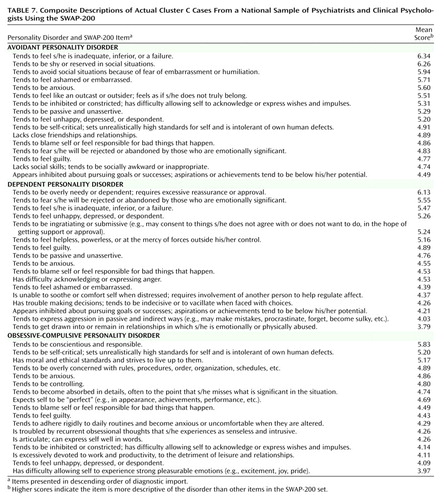

Empirically Observable Characteristics of Cluster C Personality Disorders

Avoidant and dependent personality disorders

The empirical portraits of avoidant and dependent personality disorders in Table 7 help explain the excessive comorbidity between the disorders observed in virtually every study to date, including our own (8, 46). Patients diagnosed with these disorders share a depressive or dysphoric core that appears to pervade all areas of functioning (likely reflecting the personality dimension of negative affectivity [47, 48]). This depression or dysphoria is not captured by the current DSM criteria. Patients diagnosed by their clinicians with avoidant personality disorder attempt to deal with dysphoria by keeping their distance from people, whereas those diagnosed with dependent personality disorder attempt to cope by clinging to others. However, both groups experience depression and despondency and feelings of inferiority, guilt, shame, anxiety, self-criticism, self-blame, passivity, and inhibitions. Clinicians appear to use these diagnostic categories to describe patients who might be better conceptualized as having a depressive or dysphoric personality.

Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder

The composite description (Table 7) describes patients who appear somewhat healthier than the DSM portrayal. Patients diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder in clinical practice have most of the attributes ascribed to them by DSM-IV, but are also articulate, ethical, and conscientious. They share with other cluster C patients a tendency toward dysphoric affect, manifested by depression, anxiety, guilt, and self-criticism; these features are not included in the DSM-IV criterion set. The findings are consistent with the view that the behavioral traits associated with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder serve to mask or manage underlying susceptibility to anxiety (or failure to meet overly rigid internal standards). Also notable among the most defining features of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder are a tendency to be controlling, to be inhibited or constricted, and to have a restrictive attitude toward emotion, particularly warm or tender emotions (features that hearken back to historical descriptions of obsessional neurotic style [44, 45]).

Discussion

Advantages of Expanded Criterion Sets

A consistent theme running through the findings is that DSM-IV criterion sets are too narrow. They do not capture the richness and complexity of personality syndromes as they are understood by clinicians in the community, observed empirically in patients treated in the community, or defined by DSM-IV itself in the preamble to axis II. The preamble defines personality disorders in terms of multiple domains of functioning including cognition, affectivity, interpersonal relations, and impulse regulation. However, the personality disorder criterion sets do not actually encompass these domains of functioning (18, 19).

DSM-IV limits the number of diagnostic criteria to eight or nine items per disorder, but it is clinically and psychometrically impossible for such small item sets both to describe personality syndromes in their complexity, and to describe distinct (nonoverlapping) syndromes. Certain traits play central roles in more than one personality disorder (e.g., lack of empathy is characteristic of both narcissistic and antisocial personality disorders; hostility is characteristic of paranoid, antisocial, borderline, and narcissistic personality disorders). Excluding such traits from personality disorder criterion sets leads to clinically inaccurate descriptions, but including the same item in multiple criterion sets leads to comorbidity. As now constituted, axis II cannot transcend this inherent paradox.

The paradox can be resolved by 1) expanding the size of the criterion sets, and 2) diagnosing personality disorders as configurations or gestalts rather than by tabulating individual symptoms (an approach to diagnosis we have previously addressed [10, 27]). For example, our composite descriptions of narcissistic and antisocial personality disorders contain numerous overlapping traits, yet they are conceptually distinct and would be difficult to confuse. Expanding the size of the criterion sets would 1) help bridge the gap between science and practice by making DSM personality disorder descriptions more faithful to clinical reality, 2) make the personality disorder descriptions more faithful to the theoretical construct of personality disorder (i.e., multifaceted syndromes), and 3) reduce comorbidity among personality disorders by making the diagnostic categories more distinct.

Addressing Inner Experience

A second consistent theme is that DSM-IV tends to underemphasize aspects of inner experience or mental life that are centrally defining of personality disorders; this limits both its clinical relevance and empirical fidelity. For example, the data strongly indicate that externalization and projection are central and defining features of paranoid personality disorder, yet they are not included in the DSM-IV criterion set, which instead emphasizes multiple redundant indicators of chronic suspiciousness. The data indicate that hostility, sadism, lack of empathy, lack of remorse, lack of insight, self-importance, and power-seeking are defining of antisocial personality disorder. However, these aspects of mental life are absent from the DSM description, which instead emphasizes behavioral markers such as criminality and lack of stable employment. Feelings of inadequacy and inferiority, shame, embarrassment, passivity, depression, anxiety, self-blame, and guilt appear centrally defining of avoidant and dependent personality disorders. Instead, DSM-IV emphasizes behavioral indicators of social avoidance in the former and dependency in the latter.

Some researchers may object to diagnostic criteria that address inner experience on the grounds that they are theory-laden or cannot be assessed reliably. However, DSM-IV already includes diagnostic criteria that require inferences about inner experience (e.g., lack of empathy, sense of entitlement, identity disturbance), so the issue is really one of relative emphasis. Second, our data indicate that clinicians of all theoretical persuasions can and do attend to mental life or inner experience. The omission of psychological constructs relevant to such a broad spectrum of clinicians makes personality disorder diagnosis less clinically relevant and contributes to an unnecessary schism between science and practice. Finally, the question of reliability is an empirical one. SWAP-200 personality descriptions appear as reliable as diagnoses based on structured interviews that emphasize self-report and behavioral signs. Clinical inference, when harnessed and quantified using a method such as the SWAP-200, can be highly reliable. Prior studies by Shedler and his associates (49, 50) have also demonstrated the reliability and validity of clinical inference.

Identifying Distinct Diagnoses

The present study focuses on the diagnostic categories currently defined by DSM-IV, but the findings raise broader questions about whether these categories are the optimal ones. For example, the composite descriptions of avoidant and dependent personality disorders overlap substantially and contain numerous features that may be better characterized in terms of a depressive or dysphoric personality syndrome (e.g., the tendency to feel unhappy, depressed, despondent; to feel inadequate, inferior, or a failure; to blame themselves for bad things that happen; to be inhibited about pursuing goals or successes; to feel ashamed or embarrassed; to fear rejection and abandonment; etc.). A depressive or dysphoric personality disorder category should be considered for DSM-V (9).

The findings also do not support a distinction between borderline and histrionic personality disorders as configured in the last three editions of the DSM. Patients diagnosed with these disorders share too many features to allow clear conceptual or empirical distinctions. In the evolution of the historical concept of hysterical personality style (44) to the contemporary concept of histrionic personality disorder, DSM appears to have “ratcheted up” the severity of the syndrome to a degree that renders it a borderline-spectrum disturbance (51) (what Kernberg [52] might describe as a hysterical style organized at a borderline level of functioning). Moreover, the DSM-IV criteria for borderline personality disorder fail to capture the intense emotional pain that appears central to borderline personality.

In four independent samples (9, 31, 33, 53), we have found that most patients with DSM-defined borderline and histrionic personality disorders fall into one of two empirical groupings. One group is defined by emotional dysregulation—that is, intensely painful affect that spirals out of control and often elicits desperate attempts to regulate it (e.g., self-cutting, suicidal gestures, etc.). The other group is defined by a dramatic style of affect expression, sexual seductiveness, an impulsive cognitive style, and somatization. These findings suggest different ways to draw the boundaries between histrionic and borderline personality disorders for DSM-V.

Finally, patients diagnosed with schizoid and schizotypal personality disorders share so many overlapping features that they are empirically indistinguishable. A single, combined personality disorder category might better fit the data, perhaps with an additional qualifier to indicate whether the patient has positive symptoms of schizotypy (understood as a trait, not a personality type [8]).

A Prototype Matching Approach to Diagnosis

The current DSM procedure for diagnosing personality disorders involves making present/absent judgments about a small number of diagnostic criteria, then counting the number of criteria judged “present” to determine whether the number crosses a specified threshold. When disorders are diagnosed this way, thresholds for judging criteria “present” are arbitrary for most criteria (e.g., how little empathy constitutes a lack of empathy?), and any overlap in criteria across personality disorders becomes a source of undesired comorbidity.

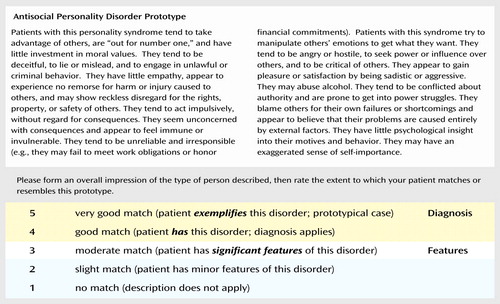

Consider instead the prototype matching approach illustrated in Figure 1. The personality disorder description or prototype is made up of statements from the composite description of actual antisocial patients (Table 5), here arranged in paragraph form. The clinician’s task is to consider the description as a whole—that is, as a configuration or gestalt—and to rate the degree of similarity or match between the prototype and a particular patient. The resulting diagnosis can be treated dimensionally (a 1–5 rating), or it can be treated categorically where a present/absent decision facilitates clinical communication (with a rating ≥4 indicating “caseness”) (10, 27).

This prototype matching method is arguably a more faithful rendition of the prototype-based approach to classification that has informed recent editions of the DSM, particularly the implementation of polythetic diagnostic decision rules (i.e., multiple criteria, none of which is necessary for diagnosis). However, the proposed prototype matching approach has several advantages. First, clinicians can consider individual criteria in the context of an overall gestalt. Each item is contextualized by the whole, and no single item can “make” or “break” the diagnosis. As a result, personality disorders with overlapping features can be clinically distinct and empirically uncorrelated (e.g., as illustrated by the composite descriptions of antisocial and narcissistic patients [9]). Second, this approach appears closer to the way clinicians make diagnoses in practice; research currently underway suggests that clinicians find a prototype-matching approach easier to apply than the symptom counting approach of DSM-IV. Third, a prototype-matching approach provides dimensional personality disorder assessments, allowing clinicians and researchers to diagnose pathology on a continuum instead of categorically diagnosing disorders as present/absent.

Limitations

This study is primarily exploratory, aimed at generating hypotheses and identifying constructs and variables for further investigation. One limitation concerns the sampling method. Although the clinicians invited to participate in the study constituted a random sample, an unknown degree of self-selection may have influenced the findings. It is probable that the reporting clinicians had a greater-than-average interest in personality and personality disorders, which may be associated with differences in training, experience, or theoretical commitments. The concern is mitigated somewhat by the fact that the sample did include clinicians of diverse theoretical orientations and practice settings, and comparable findings emerged in separate analyses stratified by theoretical orientation. However, future studies using larger samples and more rigorous sampling methods are warranted.

Selection bias may have also played a role in the clinicians’ choices regarding the patients they described. We sought to minimize this type of bias by specifying the specific personality disorder for each clinician to describe as well as other parameters, but we cannot rule it out (e.g., clinicians treating more than one patient who met the study criteria may have selected the patient who seemed more interesting or prototypical). In subsequent research we have implemented procedures to maximize the likelihood not only of random selection of clinicians but also of random selection of patients by clinicians, and similar findings are emerging.

Finally, an important limitation is that the assessors were not blind to the diagnosis of the patients they were assessing, leading to the possibility of confirmatory biases. The strongest version of this criticism is that clinicians who described current patients may have described their stereotypes or theoretical preconceptions rather than the actual characteristics of their patients. This seems implausible, given the pattern of findings that have emerged from this data set (see reference 9 for a detailed discussion). For example, the considerable discrepancy for some personality disorders between clinical prototypes and composite descriptions indicate that the clinicians were indeed describing the characteristics of their patients, not their theories. Other, more subtle confirmatory biases cannot be ruled out. Future studies (currently underway) can minimize such biases to some extent by asking clinicians to describe randomly selected patients without specific personality disorder diagnoses.

Conclusions

Perhaps the greatest challenge in personality disorder research is how to integrate the findings of empirical studies with those of the clinical consulting room. This study represents one step in the direction of integration. It draws on the combined experience of seasoned clinical practitioners, while utilizing empirical methods to harness the resulting information. We rely on clinical practitioners to do what they do best, namely making specific and detailed observations and inferences about the individual patients they know and treat. We rely on quantitative methods to do what they do best, namely aggregating data across patients to identify patterns and commonalities (36). We believe such integration of science and practice is essential to developing a classification of personality syndromes that is both empirically sound and clinically useful.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Received Sept. 11, 2001; revisions received May 29 and July 1, 2003; accepted Nov. 18, 2003. From the Graduate School of Professional Psychology, University of Denver; and the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and the Department of Psychology, Emory University, Atlanta. Address correspondence to Dr. Shedler, Graduate School of Professional Psychology, University of Denver, 2450 S. Vine St., Denver, CO 80208; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by NIMH grants MH-62377 and MH-62378. The authors thank the more than 950 clinicians for their assistance in helping to refine the SWAP-200 assessment instrument, including the 797 who participated in the present study. The authors also thank their research assistants: Michelle Levine, Alan Reyes, Lisa Goldstein, and Elizabeth Schafer.

Figure 1. Antisocial Personality Disorder Prototype

1. Livesley WJ, Jackson DN: Guidelines for developing, evaluating, and revising the classification of personality disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992; 180:609–618Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Millon T: Classification in psychopathology: rationale, alternatives and standards. J Abnorm Psychol 1991; 100:245–261Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Robins E, Guze SB: Establishment of diagnostic validity in psychiatric illness: its application to schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1970; 126:983–987Link, Google Scholar

4. Clark L: Resolving taxonomic issues in personality disorders: the value of larger scale analyses of symptom data. J Personal Disord 1992; 6:360–376Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Grove WM, Tellegen A: Problems in the classification of personality disorders. J Personal Disord 1991; 5:31–41Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Jackson DN, Livesley WJ: Possible contributions from personality assessment to the classification of personality disorders, in The DSM IV Personality Disorders. Edited by Livesley WJ. New York, Guilford, 1995, pp 459–481Google Scholar

7. Livesley WJ (ed): The DSM-IV Personality Disorders. New York, Guilford, 1995Google Scholar

8. Westen D, Shedler J: Revising and assessing axis II, part I: developing a clinically and empirically valid assessment method. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:258–272Abstract, Google Scholar

9. Westen D, Shedler J: Revising and assessing axis II, part II: toward an empirically based and clinically useful classification of personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:273–285Abstract, Google Scholar

10. Westen D, Shedler J: A prototype matching approach to diagnosing personality disorders toward DSM-V. J Personal Disord 2000; 14:109–126Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Widiger T, Frances A: The DSM-III personality disorders: perspectives from psychology. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:615–623Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Pilkonis PA, Heape CL, Proietti JM, Clark SW, McDavid JD, Pitts TE: The reliability and validity of two structured diagnostic interviews for personality disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:1025–1033Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Kellman HD, Hyler SE, Rosnick L, Davies M: Diagnosis of DSM-III-R personality disorders by two structured interviews: patterns of comorbidity. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:213–220Link, Google Scholar

14. Blais M, Norman D: A psychometric evaluation of the DSM-IV personality disorder criteria. J Personal Disord 1997; 11:168–176Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, McGlashan TH: Co-occurrence of DSM-IV personality disorders with borderline personality disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 2002; 190:552–553Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Watson D, Sinha BK: Comorbidity of DSM-IV personality disorders in a nonclinical sample. J Clin Psychol 1998; 54:773–780Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Widiger TA, Corbitt EM: Antisocial personality disorder, in The DSM-IV Personality Disorders: Diagnosis and Treatment of Mental Disorders. Edited by Livesley JW. New York, Guilford, 1995, pp 103–126Google Scholar

18. Millon T: Toward a New Psychology. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1990Google Scholar

19. Millon T, Davis RD: The place of assessment in clinical science, in The Millon Inventories: Clinical and Personality Assessment. Edited by Millon T. New York, Guilford, 1997, pp 3–20Google Scholar

20. Frances A: Categorical and dimensional systems of personality diagnosis: a comparison. Compr Psychiatry 1982; 23:516–527Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Widiger T: Categorical versus dimensional classification: implications from and for research. J Personal Disord 1992; 6:287–300Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Widiger TA, Clark LA: Toward DSM-V and the classification of psychopathology. Psychol Bull 1999; 126:947–963Google Scholar

23. Clark LA, Livesley WJ, Morey L: Personality disorder assessment: the challenge of construct validity. J Personal Disord 1997; 11:205–231Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Kim NS, Ahn W: Clinical psychologists’ theory-based representations of mental disorders predict their diagnostic reasoning and memory. J Exp Psychol 2002; 131:451–476Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Blashfield R: Exemplar prototypes of personality disorder diagnoses. Compr Psychiatry 1985; 26:11–21Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Cantor N, Genero N: Psychiatric diagnosis and natural categorization: a close analogy, in Contemporary Directions in Psychopathology: Toward the DSM-IV. Edited by Klerman GL. New York, Guilford, 1986, pp 233–256Google Scholar

27. Westen D, Heim AK, Morrison K, Patterson M, Campbell L: Classifying and diagnosing psychopathology: a prototype matching approach, in Rethinking the DSM: Psychological Perspectives. Edited by Malik M. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2002, pp 221–250Google Scholar

28. Westen D, Arkowitz-Westen L: Limitations of axis II in diagnosing personality pathology in clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1767–1771Link, Google Scholar

29. Sokal RR: Classification: purposes, principles, progress, prospects. Science 1974; 185:1115–1123Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Tyrer P: Are personality disorders well classified in DSM-IV? in The DSM IV Personality Disorders. Edited by Livesley WJ. New York, Guilford, 1995, pp 29–44Google Scholar

31. Shedler J, Westen D: Refining the measurement of axis II: a Q-sort procedure for assessing personality pathology. Assessment 1998; 5:333–353Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Block J: The Q-Sort Method in Personality Assessment and Psychiatric Research. Palo Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1978Google Scholar

33. Westen D, Shedler J, Durrett C, Glass S, Martens A: Personality diagnoses in adolescence: DSM-IV axis II diagnoses and an empirically derived alternative. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:952–966Link, Google Scholar

34. Westen D, Chang C: Personality pathology in adolescence: a review. Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 25:61–100Google Scholar

35. Horowitz L, Inouye D, Siegelman E: On averaging judges’ ratings to increase their correlation with an external criterion. J Consult Clin Psychol 1979; 47:453–458Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Rushton JP, Brainerd CJ, Preisley M: Behavioral development and construct validity: the principle of aggregation. Psychol Bull 1983; 94:18–38Crossref, Google Scholar

37. Block J: Lives Through Time. Berkeley, Calif, Bancroft, 1971Google Scholar

38. Jones EE, Hall SA, Parke LA: The process of change: the Berkeley Psychotherapy Research Group, in Psychotherapy Research: An International Review of Programmatic Studies. Edited by Crago M. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1991, pp 99–106Google Scholar

39. Shedler J, Block J: Adolescent drug use and psychological health: a longitudinal inquiry. Am Psychol 1990; 45:612–630Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Walker E, Lewine RJ: Prediction of adult-onset schizophrenia from childhood home movies of the patients. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1052–1056Link, Google Scholar

41. Cleckley H: The Mask of Sanity. St Louis, Mosby Co, 1941Google Scholar

42. Patrick CJ, Zempolich KA: Emotion and aggression in the psychopathic personality. Aggress Violent Behav 1998; 3:303–338Crossref, Google Scholar

43. Widiger T, Hare R, Rutherford M, Corbitt EM, Hart SD, Woody G, Cadoret R, Robins L, Zanarini M, Apple M, Forth A, Kultermann J, Frances A: DSM-IV antisocial personality disorder field trial. J Abnorm Psychol 1996; 105:3–16Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Shapiro D: Neurotic Styles. New York, Basic Books, 1965Google Scholar

45. MacKinnon R, Michels R: The Psychiatric Interview in Clinical Practice. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1971Google Scholar

46. Millon T, Martinez A: Avoidant personality disorder, in The DSM IV Personality Disorders. Edited by Livesley WJ. New York, Guilford, 1995, pp 218–233Google Scholar

47. Clark LA, Watson D: Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implication. J Abnorm Psychol 1991; 100:316–336Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Brown TA, DiNardo P, Lehman CL, Campbell L: Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: implications for the classification of emotional disorders. J Abnorm Psychol 2001; 110:49–58Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Shedler J, Mayman M, Manis M: The illusion of mental health. Am Psychol 1993; 48:1117–1131Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Shedler J, Karliner R, Katz E: Cloning the clinician: a method for assessing illusory mental health. J Clin Psychol 2003; 59:635–659Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Pfohl B: Histrionic personality disorder, in The DSM IV Personality Disorders. Edited by Livesley WJ. New York, Guilford, 1995, pp 173–192Google Scholar

52. Kernberg O: Borderline Conditions and Pathological Narcissism. Northvale, NJ, Jason Aronson, 1975Google Scholar

53. Bradley, R, Zittel C, Westen D: Borderline personality disorder in adolescents: phenomenology and subtypes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry (in press) Google Scholar