Depression and Other Mental Health Diagnoses Increase Mortality Risk After Ischemic Stroke

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Poststroke depression has been linked to higher mortality after stroke. However, the effect of other mental health conditions on poststroke mortality has not been examined. The objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of poststroke depression and other mental health diagnoses on mortality after ischemic stroke. METHOD: The authors examined a national cohort of veterans hospitalized after an ischemic stroke at any U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center from 1990 to 1998. Demographic, admission, and all-cause mortality data were abstracted from VA administrative databases. Chronic conditions present at discharge and new poststroke depression and other mental health diagnoses within 3 years after the stroke were identified with ICD-9 codes. Mortality hazard ratios were modeled by using Cox regression models. RESULTS: A total of 51,119 patients hospitalized after an ischemic stroke who survived beyond 30 days afterward were identified; 2,405 (5%) received a diagnosis of depression, and 2,257 (4%) received another mental health diagnosis within 3 years of their stroke. Patients with poststroke depression were younger, more often white, and less likely to be alive at the end of the 3-year follow-up period. Both poststroke depression (hazard ratio=1.13, 95% CI=1.06–1.21) and other mental health diagnoses (hazard ratio=1.13, 95% CI=1.07–1.22) independently increased the hazard for death even after other chronic conditions were controlled. CONCLUSIONS: Despite being younger and having fewer chronic conditions, a higher 3-year mortality risk was seen in patients with poststroke depression and other mental health diagnoses after hospitalization for an ischemic stroke. The biological and psychosocial mechanisms driving this greater risk should be further explored, and the effect of depression treatment on mortality after stroke should be tested.

Poststroke depression occurs in approximately one-third of all ischemic stroke survivors and has been linked to worse functional outcome, slower recovery, and worse quality of life (1–3). Prior studies have also linked depression or depressive symptoms to increased mortality for up to 10 years after a stroke, although many of these studies are limited by selection bias, small sample size, and absence of a definitive depression diagnosis (4–8). Further, depression may not exist in a vacuum after a stroke: other mental health conditions may also be present, and few studies have examined whether these diagnoses confer additional mortality risk. Knowing which mental health diagnoses are linked to higher poststroke mortality may provide better mortality risk prediction and may encourage clinicians to identify and treat these conditions more aggressively. The objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of poststroke depression and other mental health diagnoses on survival after hospitalization for ischemic stroke in a national cohort of veterans.

Method

We used U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) administrative databases to construct a national cohort of patients discharged from any VA medical center with a primary diagnosis of ischemic stroke, defined as ICD-9 codes 434 and 436 in the primary position. This strategy has at least 90% positive predictive value for identifying cases of acute ischemic stroke (9). Patients were eligible for inclusion in the database if they were discharged between October 1, 1990, and September 30, 1997. Patients hospitalized at VA medical centers in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands were excluded. For veterans with more than one admission for stroke, the first admission was considered the index event. Since DSM-IV requires depressive symptoms to be present for at least 2 weeks, we excluded stroke patients who died within 30 days of their index stroke event from this study to ensure the depression diagnosis was received poststroke (N=4,974 excluded).

From the centralized VA administrative data center we extracted demographic characteristics and summary information about episodes of inpatient care, including up to 10 ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes at discharge from the index hospitalization. We used these discharge diagnoses to construct the Charlson Index, a well-validated comorbidity index that is predictive of subsequent mortality (10, 11).

We used ICD-9 codes associated with episodes of care within 3 years poststroke to divide patients into three nonoverlapping groups: 1) those with poststroke depression, 2) those with a mental disorder or substance abuse diagnosis other than depression, and 3) those with no poststroke psychopathology. Patients diagnosed with depression comorbid with another mental disorder or substance abuse diagnosis were classified in the depressive group. Diagnosis of depression in the first 3 years poststroke was defined using ICD-9 codes 296, 298, 300.4, 309.0, 309.1, and 311. Patients with a depression ICD-9 code at index hospitalization discharge were not classified in the poststroke depression group, since these patients may have had a preexisting depression diagnosis that may or may not have been clinically symptomatic at the time of their stroke. Other mental health diagnoses were identified using ICD-9 codes for schizophrenia, major affective disorder other than depression, anxiety disorders, personality disorders, and substance abuse and dependence (list of ICD-9 codes available on request).

One potential variable of interest that may influence both the development of poststroke depression and mortality is severity of stroke. Since the national Veterans Health Administration database did not include any indicator of stroke severity, we reviewed charts of all ischemic stroke patients at our local VA medical center who were also in the national dataset. We matched each of the local patients with an ICD-9 diagnosis of poststroke depression with one local patient with another mental disorder or substance abuse diagnosis and up to three local patients with no poststroke psychopathology. All comparison patients were matched for patient age and year of stroke. We then used a previously published algorithm to abstract the written admission notes and construct a retrospective National Institutes of Health (NIH) Stroke Scale (12). We used this local subset of the national database to examine the effect of admission stroke severity on poststroke mortality.

Date of death was identified through the Beneficiary Information and Resource Locator, which does not contain information regarding the cause of death. No pharmacy data were available during the study period. Data were merged by using scrambled social security numbers and date of discharge from the index stroke admission to construct patient-level data files. This project was approved by the local institutional review board.

We compared the groups of patients with poststroke depression, other mental disorder or substance abuse diagnoses, and no poststroke psychopathology by using analysis of variance. To examine time to death, defined as the number of days between discharge from the index admission and death, we developed Cox proportional hazards models. The following independent variables were included: age, gender, ethnicity (white versus nonwhite), hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, number of discharge diagnoses, Charlson Index >2 (dichotomous), presence of depression (yes/no), and presence of other mental health or substance abuse diagnosis (yes/no). To evaluate the possibility of a cohort effect, we also examined models including a variable for year of index admission. Since including this variable did not alter hazard ratios or confidence intervals by more than 0.005, the models presented do not include year of index admission as an independent variable.

Results

We identified 51,119 patients hospitalized following an ischemic stroke who survived beyond 30 days afterward, of whom 2,405 (4.7%) received an ICD-9 diagnosis of depression and 2,257 (4.4%) received other mental disorder or substance abuse diagnoses within 3 years of their index admission (Table 1). Relative to those with no poststroke psychopathology, those with poststroke depression were younger and were less likely to be alive at the end of the follow-up period. Patients diagnosed with poststroke depression were more likely to be white relative to those with other mental disorder or substance abuse diagnoses and the no poststroke psychopathology group. The other mental disorder or substance abuse diagnosis cohort consisted of 1,369 veterans with substance abuse, 785 with anxiety disorders, 264 with schizophrenia, 207 with personality disorders, and 136 with other affective disorders. The raw numbers sum to more than 2,257 because some veterans had more than one mental disorder or substance abuse diagnosis.

In the local dataset, we identified 55 patients with poststroke depression and matched these with 47 patients with other mental disorder or substance abuse diagnoses subjects and 95 patients with no poststroke psychopathology (Table 2). Admission NIH Stroke Scale severity was not significantly different in patients with poststroke depression and those with no poststroke psychopathology (median admission ratings of 5 and 6, respectively). In a multivariate analysis of the local database, admission NIH Stroke Scale severity was not related to subsequent 3-year mortality (median NIH Stroke Scale admission ratings of 5 and 4 for those alive after 3 years versus those who died within 3 years, respectively).

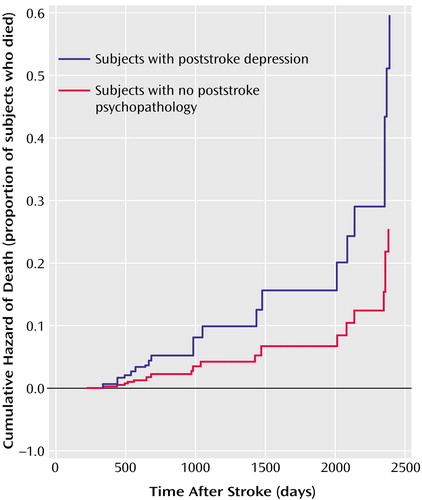

Hazard ratios for time to death are shown in Table 3. Even when we controlled for specific cardiovascular risk factors with ICD-9 diagnoses and overall mortality risk with the Charlson Index, poststroke depression independently increased the risk of death by 13%. It is important to note that the presence of other mental disorder or substance abuse diagnoses also independently conferred mortality risk of similar magnitude. Figure 1 shows the survival curve for patients with poststroke depression and patients with no poststroke psychopathology.

Discussion

This study confirms prior reports of increased long-term mortality in patients with poststroke depression and extends this finding to show that other mental health conditions are also independently associated with an increased risk of death after an ischemic stroke. We found that even after we controlled for common cardiovascular conditions and other diagnoses, mental health diagnoses in the first 3 years after stroke increase the risk of death by more than 10%. In spite of the fact that patients with poststroke depression were younger and had fewer chronic illnesses than nondepressed patients, we found that the mortality risk was still higher in those with poststroke depression and other mental health diagnoses. These data speak to the seriousness of poststroke mental health diagnoses, since the presence of a mental health condition confers as much risk for subsequent mortality as many other cardiovascular risk factors.

Although the national database did not contain data about stroke severity, we constructed a local database in order to be able to assess, albeit on a much smaller and more homogeneous sample, whether admission stroke severity was related to the development of poststroke depression and to mortality after hospital discharge. In our sample, the admission NIH Stroke Scale score was similar between groups with and without poststroke depression, and admission NIH Stroke Scale score was not predictive of subsequent mortality. While it is clear that admission stroke severity is related to early stroke mortality (13, 14), the purpose of this project was to examine the effect of poststroke depression, an outpatient diagnosis typically made weeks to months after a stroke, on long-term mortality. Patients dying within 1 month after a stroke were excluded from these analyses. Thus, the absence of a stroke severity indicator in the national administrative data set is unlikely to influence our long-term mortality models.

No studies have previously examined the impact of other mental health and substance abuse conditions on poststroke mortality. It may be that the mechanisms by which depression increases poststroke mortality risk are common to many mental disorders rather than unique to depression. Many of the disorders in the other mental disorder or substance abuse diagnosis group would be expected to predate the stroke rather than be a consequence of stroke. Potential biologic and social mechanisms by which this increased mortality risk may be incurred include psychoneurological impairments in immune functioning (15, 16), functional and cognitive disability (17, 18), unemployment (19–21), lack of exercise (22, 23), poor nutrition (24), life stress (25), and low levels of social support (26–29) and coping resources (30–32).

Other studies have also reported the association between depression or depressive symptoms and mortality after stroke (4–8). Morris and colleagues (4) reported a threefold increase in mortality during a 10-year follow-up study of a selected group of approximately 200 subjects, but this study had limited power to examine the influence of other chronic conditions on mortality. More recently, other research (5, 8) has pointed to a link between depressive symptoms and negative attitudes and mortality after stroke. Like these more recent studies, our data suggest that the association between depression and mortality after stroke is somewhat smaller than that first reported by Morris and colleagues. Studies using a continuous measure of depression symptoms, like that by House and colleagues (5), suggest that severity of depression symptoms, and perhaps specific symptoms of psychological distress and negative thoughts, may be associated with increased mortality risk. Since we had only a dichotomous diagnosis of depression, we were not able to assess the association between depression severity or specific depression symptoms and poststroke mortality.

The relationship between depression and increased risk of mortality has also been seen in other conditions, especially after cardiovascular disease (33–36). The mechanisms by which depression may be increasing mortality risk in these conditions is not known, although both physiologic (16, 17, 37) and biopsychosocial (19–33, 38–40) associations have been suggested. Future work should focus on both the physiologic and psychosocial mechanisms by which mental health conditions may confer excess mortality risk so that effective interventions can be developed and tested to reduce poststroke mortality.

This study has several limitations. We used administrative data and thus had limited clinical severity indicators and had to use ICD-9 diagnoses to identify clinical conditions. This likely resulted in an underdiagnosis of depression and other mental disorder or substance abuse diagnoses. It is possible that more severely affected patients are more likely to receive an ICD-9 diagnosis of depression, thus these results may pertain only to patients with more severe depression. Likewise, we are unable to examine possible behavioral and biologic links between depression and increased stroke mortality like sedentary lifestyle and increased inflammation and platelet adhesion. We recognized that stroke severity might be an important mediating variable and so evaluated it in a local subset of the national dataset. Although stroke severity was not a predictor of mortality in this analysis, it is possible that the smaller number of deaths in this dataset limited our power to examine the effect of initial stroke severity on long-term mortality. It is possible that sicker patients have greater utilization of health care and thus have more opportunity for a depression diagnosis (ascertainment bias), but in our study poststroke depression and other mental disorder or substance abuse diagnoses were not independently predictive of inpatient utilization poststroke (data not shown). The possibility of residual confounding between unmeasured physical, mental, and social factors is always present in analyses of large administrative databases. However, our findings do correspond to other literature on depression and mortality after stroke, including prospective studies with more sensitive measures of depression. Finally, although our cohort contained more than 1,000 women stroke survivors, the Veterans Health Administration is a unique sample of mostly chronically ill, socioeconomically disadvantaged men. Further studies are needed to examine whether these relationships are also observed in other more heterogeneous populations.

Despite these limitations, these data show that both poststroke depression and other mental health diagnoses are associated with increased mortality risk after stroke. While the precise mechanisms underlying these associations are not known, these findings have important implications for stroke research and for clinical care. Researchers evaluating mortality after stroke should consider including depression and other mental health diagnoses in multivariate models of long-term stroke mortality. Clinicians treating stroke patients should be alert to the diagnosis and treatment of both depression and other mental health diagnoses. Whether treating poststroke depression and other mental health conditions not only improves patient symptoms but also reduces subsequent mortality risk remains an important, unanswered question.

|

|

|

Received May 27, 2003; revision received Sept. 16, 2003; accepted Sept. 19, 2003. From the Roudebush VA Medical Center, Health Services Research and Development; the Department of Neurology, Indiana University School of Medicine, Bloomington; the Regenstrief Institute for Health Care, Indianapolis; the Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, Md.; Outcomes Research U.S. Medical Division, Eli Lilly, Inc., Indianapolis; and the Department of Psychology, Indiana University-Bloomington. Address reprint requests to Dr. Williams, Roudebush VAMC, HSR&D 11H, 1481 West 10th St., Indianapolis, IN 46202; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a Research Career Development Award to Dr. Williams from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. Construction of the database was supported by a contract from Bristol Myers Squibb, Inc. The authors thank Lori Mamlin, M.S., M.B.A., and Ian Welsh, M.S., for their contributions during the construction of the database.

Figure 1. Cumulative Hazard of Death Over Time in Patients With and Without Depression From a National Cohort of Veterans Hospitalized Following an Ischemic Strokea

aPatients who died within the first 30 days poststroke were excluded. Veterans with ICD-9 diagnoses of depression within 3 years poststroke had an increased hazard of death relative to those without depression or other mental health diagnosis; this increased risk of death appeared early and became more pronounced over time.

1. Parikh RM, Robinson RG, Lipsey JR, Starkstein SE, Fedoroff JP, Price TR: The impact of poststroke depression on recovery in activities of daily living over a 2-year follow-up. Arch Neurol 1990; 47:785–789Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Ramasubbu R, Robinson RG, Flint AJ, Kosier T, Price TR: Functional impairment associated with acute poststroke depression: the Stroke Data Bank Study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998; 10:26–33Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kauhanen ML, Korpelainen JT, Hiltunen P, Brusin E, Mononen H, Maatta, R, Nieminen P, Sotaniemie KA, Myllyla VV: Poststroke depression correlates with cognitive impairment and neurological deficits. Stroke 1999; 30:1875–1880Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Morris PLP, Robinson RG, Andrzejewski P, Samuels J, Price TR: Association of depression with 10-year poststroke mortality. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:124–129Link, Google Scholar

5. House A, Knapp P, Bamford J, Vail A: Mortality at 12 and 24 months after stroke may be associated with depressive symptoms at 1 month. Stroke 2001; 32:696–701Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Everson S, Roberts R, Goldberg D, Kaplan G: Depressive symptoms and increased risk of stroke mortality over a 29-year period. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158:1133–1139Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Anderson CS, Jamrozik KD, Broadhurst RJ, Stewart-Wynne EG: Predicting survival for 1 year among different subtypes of stroke: results from the Perth Community Stroke Study. Stroke 1994; 25:1935–1944Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Lewis SC, Dennis MS, O’Rourke LJ, Sharpe M: Negative attitudes among short-term stroke survivors predict worse long-term survival. Stroke 2001; 32:1640–1645Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Benesch C, Witter DM Jr, Wilder AL, Duncan PW, Samsa GP, Matchar DB: Inaccuracy of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9-CM) in identifying the diagnosis of ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Neurology 1997; 49:660–664; correction, 1998; 50:306Google Scholar

10. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR: A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987; 5:373–383Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA: Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992; 45:613–619Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Williams LS, Yilmaz E, Lopez-Yunez AM: Retrospective assessment of initial stroke severity with the NIH Stroke Scale. Stroke 2000; 31:858–862Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Henon H, Godefroy O, Leys D, Mounier-Vehier F, Lucas C, Rondepierre P, Duhamel A, Pruvo JP: Early predictors of death and disability after acute cerebral ischemic event. Stroke 1995; 26:392–398Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Petty GW, Brown RD Jr, Whisnant JP, Sicks JD, O’Fallon WM, Wiebers DO: Ischemic stroke: outcomes, patient mix, and practice variation for neurologists and generalists in a community. Neurology 1998; 50:1669–1678Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, McGuire L, Robles TF, Glaser R: Emotions, morbidity, and mortality: new perspectives from psychoneuroimmunology. Ann Rev Psychol 2002; 53:83–107Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Licinio J, Wong ML: The role of inflammatory mediators in the biology of major depression: central nervous system cytokines modulate the biological substrate of depressive symptoms, regulate stress-responsive systems, and contribute to neurotoxicity and neuroprotection. Mol Psychiatry 1999; 4:317–327Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Coe RM, Romeis JC, Miller DK, Wolinsky FD, Virgo KS: Nutritional risk and survival in elderly veterans: a five-year follow-up. J Community Health 1993; 18:327–334Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Scott WK, Macera CA, Cornman CB, Sharpe PA: Functional health status as a predictor of mortality in men and women over 65. J Clin Epidemiol 1997; 50:291–296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Amick BC III, McDonough P, Chang H, Rogers WH, Pieper CF, Duncan G: Relationship between all-cause mortality and cumulative working life course psychosocial and physical exposures in the United States labor market from 1968 to 1992. Psychosom Med 2002; 64:370–381Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Kasprow WJ, Rosenheck R: Mortality among homeless and nonhomeless mentally ill veterans. J Nerv Ment Dis 2000; 188:141–147Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Stewart JM: The impact of health status on the duration of unemployment spells and the implications for studies of the impact of unemployment on health status. J Health Econ 2001; 20:781–796Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Morey MC, Pieper CF, Crowley GM, Sullivan RJ, Puglisi CM: Exercise adherence and 10-year mortality in chronically ill older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50:1929–1933Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Davidson S, Judd F, Jolley D, Hocking B, Thompson S, Hyland B: Cardiovascular risk factors for people with mental illness. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2001; 35:196–202Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Coe RM, Romeis JC, Miller DK, Wolinsky FD, Virgo KS: Nutritional risk and survival in elderly veterans: a five-year follow-up. J Community Health 1993; 18:327–334Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Krause N: Stressors in highly valued roles, religious coping, and mortality. Psychol Aging 1998; 13:242–255Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Dalgard OS, Lund Haheim L: Psychosocial risk factors and mortality: a prospective study with special focus on social support, social participation, and locus of control in Norway. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998; 52:476–481Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Hanson BS, Isacsson SO, Janzon L, Lindell SE: Social network and social support influence mortality in elderly men: the prospective population study of “men born in 1914,” Malmo, Sweden. Am J Epidemiol 1989; 130:100–111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Roberts H, Pearson JC, Madeley RJ, Hanford S, Magowan R: Unemployment and health: the quality of social support among residents in the Trent region of England. J Epidemiol Community Health 1997; 51:41–45Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Seeman TE: Health promoting effects of friends and family on health outcomes in older adults. Am J Health Promot 2000; 14:362–370Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Frentzel-Beyme R, Grossarth-Maticek R: The interaction between risk factors and self-regulation in the development of chronic diseases. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2001; 204:81–88Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Merlo J, Ostergren PO, Mansson NO, Hanson BS, Ranstam J, Blennow G, Isacsson SO, Melander A: Mortality in elderly men with low psychosocial coping resources using anxiolytic-hypnotic drugs. Scand J Public Health 2000; 28:294–297Medline, Google Scholar

32. Pennix BW, van Tilburg T, Kriegsman DM, Deeg DJ, Boeke AJ, van Eijk JT: Effects of social support and personal coping resources on mortality in older age: the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Am J Epidemiol 1997; 146:510–519Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Arfken CL, Lichtenberg PA, Tancer ME: Cognitive impairment and depression predict mortality in medically ill older adults. J Gerontol 1999; 54A:M152-M156Google Scholar

34. Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Talajic M: Coronary heart disease/myocardial infarction: depression and 18-month prognosis after myocardial infarction. Circulation 1995; 91:999–1005Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Juneau M, Theroux P: Depression and 1 year prognosis in unstable angina. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160:1354–1360Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Ladwig KH, Roll G, Briehardt G, Buddle T, Borggrefe M: Post-infarction depression and incomplete recovery 6 months after acute myocardial infarction. Lancet 1994; 343:20–23Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Laghrissi-Thode F, Wagner S, Pollock B, Johnson P, Finkel M: Elevated platelet factor 4 and beta-thromboglobulin plasma levels in depressed patients with ischemic heart disease. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 42:290–295Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Carney R, Freedland K, Eisen S, Rich M, Jaffe A: Major depression and medication adherence in elderly patients with coronary artery disease. Health Psychol 1995; 14:88–90Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Joynt KE, Whellan DJ, O’Connor CM: Depression and cardiovascular disease: mechanisms of interaction. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 54:248–261Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Desai MM, Perlin JB: Quality of preventive medical care for patients with mental disorders. Med Care 2002; 40:129–136Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar