Lack of Association Between Behavioral Inhibition and Psychosocial Adversity Factors in Children at Risk for Anxiety Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: In a previous controlled study of offspring at risk for anxiety disorders, the authors found that parental panic disorder with comorbid major depression was associated with child behavioral inhibition, the temperamental tendency to be quiet and restrained in unfamiliar situations. To explore whether this association was mediated by environmental factors, the authors examined associations between psychosocial adversity variables and behavioral inhibition in this group of children. METHOD: Subjects included 200 offspring of parents with panic disorder and/or major depression and 84 comparison children of parents without mood or anxiety disorders. Behavioral inhibition was assessed through laboratory observations. The associations between behavioral inhibition and the following psychosocial factors were examined: socioeconomic status; an index of adversity factors found in previous studies to be additively associated with child psychopathology; family intactness, conflict, expressiveness, and cohesiveness; exposure to parental psychopathology; sibship size; birth order; and gender. RESULTS: The results showed no associations between behavioral inhibition and any of the psychosocial factors in the study group as a whole, despite adequate power to detect medium effect sizes. Among low-risk comparison children only, some definitions of behavioral inhibition were associated with low socioeconomic status, low family cohesion, and female gender. CONCLUSIONS: The results suggest that the psychosocial adversity factors examined in this study do not explain the previous finding that offspring of parents with panic disorder are at high risk for behavioral inhibition.

The term “behavioral inhibition” refers to a temperamental tendency to show fear or quiet restraint when exposed to unfamiliar people or situations (1). Our group previously reported a higher rate of behavioral inhibition among 2- to 6-year-old offspring of parents with panic disorder with comorbid major depression, compared with offspring of parents who had no anxiety or mood disorders (2). This report was consistent with previous studies in smaller groups of subjects that found an association between parental panic disorder and child behavioral inhibition (3–5), as well as with studies suggesting that children with behavioral inhibition were more prone to develop childhood anxiety disorders (6–10).

Although previous findings suggest that behavioral inhibition may represent an early index of genetically transmitted “anxiety proneness,” the onset or maintenance of behavioral inhibition in a child at risk could also be influenced by environmental factors associated with living with a parent with panic disorder and major depression. For example, parental anxiety or depression may contribute to a more adverse family environment. Rutter and Quinton (11) have identified multiple psychosocial factors as additive risk factors for child psychopathology, including marital conflict, large family size, low socioeconomic status, and exposure to maternal psychopathology. Although numerous studies have documented associations between these factors, in combination or individually, and externalizing disorders (12–17), a substantial number of reports have noted links with internalizing disorders as well (13, 18), including anxiety disorders (12, 15, 17). The findings suggest that these adversity factors might be hypothesized to be associated with behavioral inhibition as well. Parents with psychiatric illnesses may have lower levels of educational and occupational achievement and therefore lower socioeconomic status. The hardship of difficult economic conditions and their associated stressors might contribute to behavioral inhibition in the child. For example, it has been shown that primate infants reared in experimental conditions with unpredictable foraging opportunities, where mother monkeys were periodically required to work hard to obtain full food rations, developed anxious/avoidant behaviors similar to those of inhibited infants (19).

Moreover, parents afflicted with mood or anxiety disorders may model or encourage anxious or avoidant behaviors. Indeed, primate studies of analogues of inhibited temperament (19–22) and prospective studies of human infants and toddlers (23, 24) have suggested that parental behaviors may mitigate or exacerbate the onset or maintenance of behavioral inhibition, even among primates genetically disposed to be inhibited. In the absence of detailed intensive observations of parent-child interactions, assessment of factors related to parental behaviors can be challenging. However, modeling may be assessed by comparing the times of onset and offset of parental disorder with the child’s age to examine whether the child was exposed to parental psychopathology. This approach, for example, has revealed associations between exposure to parental psychopathology and impairment among children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (25). In our study, we hypothesized that children exposed to parental psychopathology would be more likely to manifest behavioral inhibition than those with a parent who had an anxiety or mood disorder only before the child was born.

Finally, irrespective of parental psychopathology, it has been suggested that other aspects of the social or familial environment might influence behavioral inhibition. For example, Kagan and colleagues (1) found an association between late birth order and behavioral inhibition in one of their study groups, and they speculated that teasing or roughness by older peers might contribute to inhibition in late-born children. Similarly, it has been suggested that inhibited behavior may be more socially acceptable in girls, whereas boys may encounter more pressure from parents, peers, and teachers to be bolder and willing to approach unfamiliar phenomena (8). Accordingly, some studies have found corresponding gender differences in rates or stability of behavioral inhibition (8, 10, 26, 27), although others have not (28, 29).

Understanding the mechanism of transmission of behavioral inhibition to offspring at risk for panic disorder and depression could help inform the development of preventive interventions. As several studies have suggested, young children with behavioral inhibition appear to have increased risk for developing social anxiety disorder (8, 10, 30) or other anxiety disorders with social anxiety as a prominent feature (6, 7), particularly if their parents also have anxiety disorders (30, 31). These social anxiety sequelae appear early in childhood or adolescence, and children with behavioral inhibition whose parents have panic disorder and depression may be at further risk for other disorders later in life. If particular environmental stressors can be shown to influence the development of behavioral inhibition, efforts to remediate these stressors or to buffer children from their effects might help prevent behavioral inhibition and its sequelae. If, in contrast, psychosocial stressors do not appear to affect rates of behavioral inhibition among children at risk, then preventive interventions, including cognitive behavior or psychopharmacological approaches, might be more efficiently targeted toward the symptoms of behavioral inhibition itself or their social anxiety sequelae.

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether behavioral inhibition in a group of children at risk for anxiety disorders was associated with an adverse psychosocial environment. To this end, we examined associations with psychosocial factors hypothesized on the basis of previous studies to be associated with child psychopathology or with behavioral inhibition. These factors include a conflictual family environment; Rutter and Quinton’s indicators of adversity (11); exposure to parental panic disorder, agoraphobia, or major depression; late birth order; and female gender. We hypothesized that there would be an association of behavioral inhibition with each of these variables.

Method

The methods have been described in detail in a prior report (2). Briefly, participants were recruited from clinical settings and through advertisements for a study of temperament and psychopathology in children of parents treated for panic disorder and comparison children. The participants were 284 children between the ages of 21 months and 6 years, including 129 children from 102 families in which one or both parents had both panic disorder and major depression, 22 children from 17 families in which one or both parents had panic disorder without major depression, 49 children from 37 families in which one or both parents had major depression without panic disorder, and 84 children from 60 families in which parents had neither depression nor major anxiety disorders (comparison subjects). Potential comparison parents were included only if they and their spouse did not meet the DSM-III-R criteria for lifetime panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), generalized anxiety disorder, major depression, bipolar disorder, or dysthymia. We did not exclude other disorders because we did not want to create a “super-normal” comparison group. Similarly, no proband parents with panic disorder or major depression were excluded on the basis of comorbid psychiatric disorders. The study was approved by the institutional review board of our hospital. After a complete description of the study, the parents provided written informed consent for themselves and their children. The children provided assent to the study procedures.

Diagnostic Assessments of Parents

Both parents were interviewed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (32) to assess past and current axis I diagnoses and antisocial personality disorder. Interviews were conducted by raters supervised by two senior psychiatrists (J.R. and J.B.). The diagnosticians were blind to the parents’ ascertainment group, to all nonpsychiatric data, and to all information about other family members. On the basis of 173 interviews, the kappa coefficients of agreement between the study interviewers and three board-certified psychiatrists who listened to audiotaped interviews made by the raters were 0.86 for major depression, 0.96 for panic disorder, and 0.90 for agoraphobia.

Laboratory Assessment of Behavioral Inhibition

Behavioral inhibition was assessed by using age-specific protocols that measured the child’s reaction to unfamiliar people, rooms, objects, and test procedures, as previously reported (2). Separate 90-minute protocols were used for children in the age ranges centered on 2, 4, and 6 years; each child was assessed once. In these protocols, the child, with the mother present, encountered a variety of unfamiliar procedures and tasks, including physiological measurements and cognitively challenging tasks administered by an unfamiliar female examiner, and their behavioral responses were observed and quantified. Interrater reliability for 20 randomly selected videotaped assessments of temperament were as follows: intraclass correlation (ICC)=0.89 for the number of spontaneous comments, ICC=0.82 for the number of smiles, and kappa=0.70 for the global rating of behavioral inhibition. Four definitions of behavioral inhibition were used.

| 1. | Dichotomous behavioral inhibition: Two-year-olds were categorized as inhibited if they displayed ≥4 fears or showed minimal vocalization or smiling. Four-year-olds and 6-year-olds were so classified if they made fewer spontaneous comments and smiles than the lowest 20th percentile of comparison children in their age range. | ||||

| 2. | Global behavioral inhibition (rated for 4- and 6-year-olds only): The rating of global behavioral inhibition was made on a 4-point scale on the basis of the child’s behavior across the laboratory battery (scores could range from 1, extremely uninhibited, to 4, extremely inhibited). Children who received ratings of 3 or 4 were considered inhibited. | ||||

| 3. | Summary behavioral inhibition: The summary score was derived from a principal factors factor analysis with varimax rotation of all behavioral variables rated, computed separately for 2-, 4-, and 6-year-old children (see reference 2 for a complete list of variables). Children whose summary score was in the range of the scores for the upper 20th percentile of comparison children in their age range were classified as inhibited. | ||||

| 4. | Consensus behavioral inhibition: To derive a more stringent definition of behavioral inhibition, we classified 2-year-old children as having behavioral inhibition if they met the criteria for both definitions for which they were eligible and 4- and 6-year-olds as having behavioral inhibition if they met the criteria for two of the three definitions. | ||||

Measures of Psychosocial Adversity

Measures of psychosocial adversity included family conflict, Rutter and Quinton’s indicators of adversity (11), and exposure to parental psychopathology. Family conflict was assessed by using the Family Environment Scale, a self-report true-false measure that assesses the quality of interpersonal relationships among family members; the measure has high internal and test-retest reliability, and norms are available (33, 34). The Family Environment Scale was completed by both parents in each family with reference to their current family relationships. They were then asked to complete the measure a second time if there had ever been a time in the past when they would have answered the questions very differently. Both parents’ scores on each of six measures (past and current cohesion, conflict, and expressiveness scales) were compared, and the more adverse score was used in the analyses.

In their study of indicators of adversity, Rutter and Quinton (11) reported on six aspects of the family environment that correlated significantly with childhood psychiatric disorders. The aggregate of these factors, and not any one in particular, significantly increased the risk for mental disorder in children. Other work suggested that the risk to children increased proportionally to the number of risk factors present (14). As in prior studies from our center (16, 17), an index of factors identified in Rutter and Quinton’s work as being associated with childhood psychiatric disorders was derived by adding the number of the following factors that were present: 1) low social class (socioeconomic status III, IV, V) assessed with the Hollingshead Four-Factor Index (35), 2) large family size (three or more children), 3) paternal criminality (presence of antisocial personality in the father), 4) exposure to maternal mental disorder, and 5) severe marital discord. The sixth factor, placement in foster care, was not assessed, since no children in the current study had been placed outside the home. As in previous studies from our center (16, 17), we indexed exposure to maternal mental disorder by the presence of two or more psychiatric disorders in the mother during the child’s lifetime. These disorders included major depression, bipolar disorder, dysthymia, panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, specific phobia, OCD, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol abuse or dependence, substance abuse or dependence, anorexia, bulimia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and antisocial personality disorder. Marital discord was approximated by using scales from the Family Environment Scale. The summary measure of family conflict was defined as a linear combination of the Family Environment Scale subscales (cohesion, expressiveness, and conflict). These subscales assess the quality of interpersonal relationships between family members. This measurement has been previously used by members of our group (16, 17). For each of the three Family Environment Scale scales rated, we defined persistent adversity as being present if both the current and past scores were more than 1.5 standard deviations in the direction of more adversity than the mean for the comparison families (i.e., more adversity was indicated by higher scores for conflict and lower scores for cohesion and expressiveness). We then computed a family adversity summary score consisting of a linear combination of the six standardized Family Environment Scale scales (past and present cohesion [reversed], conflict, and expressiveness [reversed]) and of the three standardized adversity scales; the summary score was dichotomized with reference to the median score of the comparison group.

Exposure to parental psychopathology was rated on the basis of information obtained with the SCID. Whenever parents endorsed a symptom in the SCID interview, they were queried about its onset and offset, so that age at onset and offset of each lifetime diagnosis could be determined. We then used the parent’s date of birth and ages at onset and offset of disorders and the child’s date of birth to create three-tiered exposure variables for each disorder indicating whether the parent 1) never had the disorder (“0, no disorder”), 2) had the disorder only before the child’s birth (“1, disorder present without exposure”), or 3) had the disorder during the child’s lifetime (“2, disorder present with exposure”). Because onsets and offsets were given to the nearest year, when a disorder offset was reported for the year a child was born, the child was classified as having no exposure to the disorder. Similarly, if a disorder onset was reported for the same year as the behavioral inhibition assessment, the child was classified as having been exposed to the disorder.

Data Analysis

Each of the four definitions of behavioral inhibition was tested for its association with each environmental variable assessed. The study group included multiple siblings from some families, and because family members cannot be considered independently sampled since they share genetic, cultural, and social risk factors, for all comparisons we used a generalized estimating equation method to estimate general linear models (36), as implemented in Stata (37). Unlike standard linear or logistic regression models, generalized estimating equation models produce consistent standard errors and p values in the presence of intrafamilial clustering. We chose specific models to conform to the distribution of the variable: for binary outcomes, we used the binomial family and a logit link function; for ordinal outcomes, we used the Poisson family and a log link function. We used Wald’s test to assess the statistical significance of individual regressors. We used Fisher’s exact test in place of a generalized estimating equation when there were one or more zero frequencies in the two-way table defined by the categorical predictor and dichotomous outcome. Since previous studies have suggested that the number of Rutter and Quinton’s indicators of adversity has a linear relationship to worse outcome, we also tested Rutter and Quinton’s index against continuous measures of behavioral inhibition, namely, the proportion of behavioral inhibition definitions met and the number of smiles and comments the child made during the laboratory assessment. All tests were two-tailed, with alpha set at 0.05.

When associations between behavioral inhibition and environmental variables were found, parental diagnostic status (a four-level categorical variable indicating the diagnostic group from which the parent was drawn) was tested for its association with the variable in question and was covaried if it was significantly related, since parental diagnostic status was known to be related to behavioral inhibition and might otherwise have confounded the associations. Because variables might have different patterns of association with behavioral inhibition among offspring at risk versus comparison offspring, we also tested each variable’s association with behavioral inhibition in the group of comparison children (N=84).

To assess exposure to parental psychopathology, for each disorder (panic disorder, depression, agoraphobia, any anxiety disorder, or any mood disorder), we tested the effects of the three-tiered familial risk variable (no parental disorder, parental disorder without exposure, parental disorder with exposure) on the rate of behavioral inhibition in the children. In each of these analyses, the three-tiered variable was coded as an indicator variable so that, for equations found to be significant overall, comparisons could be made between levels of the variable. In particular, we were interested in the comparison between rates of behavioral inhibition in children who were exposed to parental disorder and rates of behavioral inhibition in children whose parents had a disorder to which the child was not exposed. Socioeconomic status was included in these analyses in order to control for its potential confounding effects, since it was associated both with parental diagnostic status and with behavioral inhibition.

Results

Associations With Psychosocial Adversity Factors

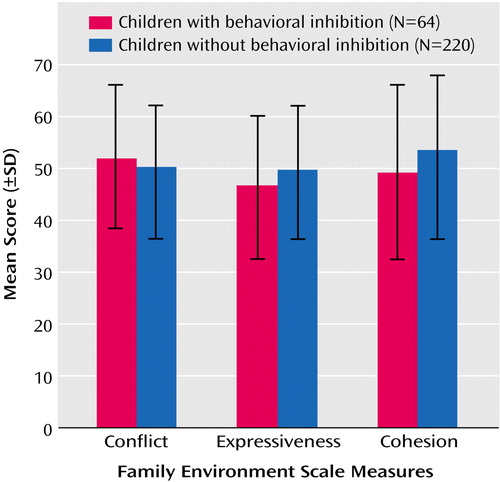

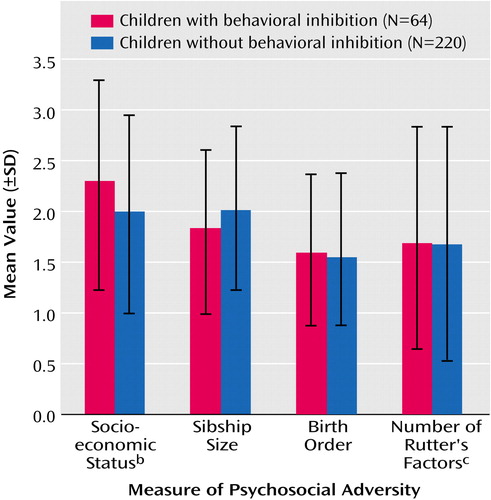

There were no significant associations between behavioral inhibition and any of the measures of psychosocial adversity examined. The figures present associations with these factors for children classified by using the dichotomous behavioral inhibition definition; however, no differences were found when the other definitions of behavioral inhibition were used. As Figure 1 shows, children with and without behavioral inhibition did not differ in rates of family conflict, expressiveness, or cohesion. Similarly, as Figure 2 shows, they did not differ in socioeconomic status (after parental diagnostic status, also related to socioeconomic status, was covaried), sibship size, or birth order or in the mean number of Rutter and Quinton’s adversity factors. Moreover, the number of Rutter and Quinton’s indicators of risk was not significantly associated with the proportion of behavioral inhibition definitions met (Wald χ2=0.13, df=1, p=0.72) or with the number of smiles (Wald χ2=0.35, df=1, p=0.55) or spontaneous comments (Wald χ2=0.25, df=1, p=0.61) the child made during the assessment battery (in univariate tests or in tests in which the child’s age was controlled). These negative findings occurred in a sample sufficiently large that our power to detect a medium effect size (Cohen’s d=0.5) was greater than 90%.

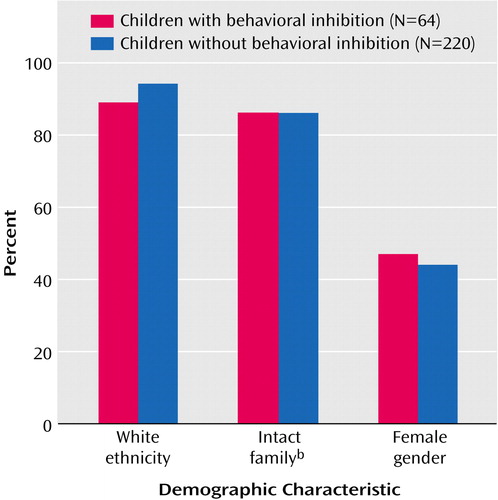

As Figure 3 shows, no associations were noted either for family intactness (whether the child was living with both biological parents) or ethnicity (white or nonwhite). In general, gender did not differ significantly between children with and without behavioral inhibition; only by using the global behavioral inhibition definition did the difference reach significance (54% of the children with behavioral inhibition were female, compared with 40% of the children without behavioral inhibition) (Wald χ2=3.99, df=1, odds ratio=1.72, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.01–2.94, p<0.05).

When associations were examined within the comparison families only (where neither parent had a mood or major anxiety disorder), only a few associations were found, and they were not consistent across definitions. Poorer socioeconomic status was associated with dichotomous behavioral inhibition only (for children with [N=10] versus those without [N=74] behavioral inhibition: mean=2.40, SD=1.07, versus mean=1.66, SD=0.91; Wald χ2=4.49, df=1, p<0.04; odds ratio=1.93, 95% CI=1.05–3.53), and lower family cohesiveness was associated with summary behavioral inhibition (for children with [N=18] and children without [N=63] behavioral inhibition: mean=53.8, SD=13.4, versus mean=60.1, SD=6.8; Wald χ2=6.42, df=1, p<0.02; odds ratio=0.93, 95% CI=0.89–0.98) and with consensus behavioral inhibition (for children with [N=18] versus those without [N=63] behavioral inhibition: mean=54.2, SD=13.7, versus mean=60.0, SD=6.7; Wald χ2=5.36, df=1, p<0.03; odds ratio=0.94, 95% CI=0.89–0.99). Female gender was significantly associated with global behavioral inhibition (in children with [N=20] versus those without [N=53] behavioral inhibition: 60.0% versus 32.1% were female; Wald χ2=4.28, df=1, p<0.04; odds ratio=3.11, 95% CI=1.06–9.13) and with summary behavioral inhibition (in children with [N=18] versus those without [N=63] behavioral inhibition: 61.1% versus 34.8% were female; Wald χ2=3.82, df=1, p=0.05; odds ratio=2.82, 95% CI=1.0–7.97).

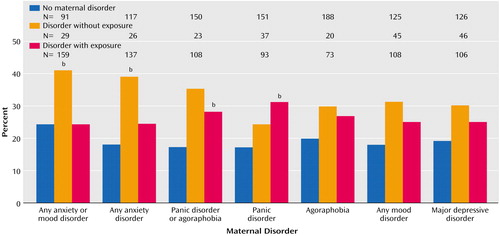

Associations With Exposure to Maternal Psychopathology

Because fathers with panic disorder, agoraphobia, and major depression were uncommon in our study group (N=31, N=23, and N=66, respectively), we did not have adequate power to examine associations between behavioral inhibition and exposure to paternal disorders; therefore we restricted our analysis to exposure to mothers’ disorders. As Figure 4 shows, our hypothesis that rates of behavioral inhibition would be higher among children exposed to maternal psychopathology than among children whose mothers had the disorder only before they were born was not supported. For all comparisons involving all disorders, except panic disorder, raw rates of behavioral inhibition were higher among the children whose mothers had these disorders before they were born. In addition, for the general category denoting the presence of any anxiety or mood disorder, the rate of behavioral inhibition in the disorder-without-exposure group was significantly higher than that in the group with no maternal disorders. The difference for panic disorder did not reach significance, despite a large enough number of subjects to detect a relative risk of 2.175 with 80% power. No significant differences were found for any of the other behavioral inhibition definitions; for all comparisons (including comparisons for maternal panic disorder), the rates were either higher or not more than 5 percentage points lower in the disorder-without-exposure group.

To determine whether behavioral inhibition was related to current symptoms in the mothers, we examined associations of current anxiety and mood disorders and current DSM-III-R Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF) scores with child behavioral inhibition status. No significant associations were found between child behavioral inhibition and the number of maternal anxiety disorders (odds ratio=1.2, p=0.07; odds ratio with parental diagnostic status covaried=1.1, p=0.46), number of maternal mood disorders (odds ratio=1.2, p=0.51), presence of any (one or more) anxiety disorder (odds ratio=1.5, p=0.16), presence of any (one or more) mood disorder (odds ratio=1.4, p=0.30), or current GAF scores (odds ratio=1.0, p=0.08; odds ratio with parental diagnostic status covaried=1.0, p=0.89).

Discussion

This study explored whether higher rates of behavioral inhibition among children of parents with panic disorder and major depression might be accounted for by psychosocial adversity factors previously found to be associated with childhood psychopathology. We found no significant associations between any of the multiple measures of adversity examined and any of the definitions of behavioral inhibition. The only factor significantly linked to behavioral inhibition in the overall study group was female gender, and this association was found only for one of the four definitions of behavioral inhibition.

These results suggest that the psychosocial factors we examined do not explain the link between behavioral inhibition and maternal panic disorder and agoraphobia. The findings are consistent with twin studies suggesting that behavioral inhibition has a moderate to high heritability, with estimates of heritability rates ranging from 0.40 to 0.70 (26, 38–40). Studies of non-at-risk children have found moderate heritability of behavioral inhibition across toddlerhood (26), as well as higher monozygotic than dizygotic concordance for change in behavioral inhibition status over time (39–41). One study suggested that heritability rates were higher when the analysis was restricted to children with extreme behavioral inhibition or extreme lack of inhibition (one standard deviation above or below the mean) (e.g., >70% at 2 years of age); however, the accuracy of the estimate is limited by the small number of subjects (26, 40). As Plomin (42) and others have discussed, the twin study literature has suggested that the nongenetic variance in anxiety disorders appears attributable to environmental influences unique to the individual rather than to aspects of the family environment common to all siblings. Our results are consistent with this hypothesis for behavioral inhibition in offspring at risk, in finding no associations with family-wide adversity factors such as conflictual relations and low socioeconomic status. Exposure to maternal disorder, which arguably may represent an “unshared” influence, since it may differ between siblings in a family, similarly showed no association. Further studies are needed to examine other possible nonshared environmental influences on behavioral inhibition.

The lack of association between behavioral inhibition and the psychosocial adversity factors we examined contrasts with cross-sectional and longitudinal studies that have documented associations between adversity factors and both externalizing (13, 15–17, 25, 43) and internalizing (12, 13, 15, 1843) disorders in children (11, 44, 45). For example, in their study on the Isle of Wight, Rutter and Quinton (11) found that the aggregate of severe marital conflict, low social class, large family size, paternal criminality, maternal mental disorder, and foster placement conferred higher risk for mental disturbance in the child. In their study of youth in inner London, Rutter and Quinton (12) found that anxious depressed behavior was associated with exposure to parental hostile behavior. In the Ontario Child Health study, low income and family dysfunction predicted onset and maintenance of psychiatric disorders in children over a 4-year period (45). Similarly, in the New York Child Longitudinal Study (15), low socioeconomic status was significantly associated with all disruptive behavior disorders and with separation anxiety disorder at 8-year-follow-up (range of odds ratios: 2.2–2.7). In a large Puerto Rican study that included 4–16-year-olds, low socioeconomic status was cross-sectionally associated with oppositional disorder, ADHD, depression, and separation anxiety disorder; marital disharmony and family dysfunction were associated with oppositional disorder and depression, respectively (13). Using the same methods that were used in the present study, Biederman and colleagues (16, 17) found that among clinically referred youths with ADHD and comparison youngsters, the risk for ADHD (16, 17) and associated comorbidity, including mood and anxiety disorders (17), increased as the number of Rutter and Quinton’s adversity indicators increased. Moreover, again using the same methods used in the present study, they found significant associations between children’s ADHD status and multiple measures of family adversity, including parental conflict, decreased cohesion, and exposure to maternal psychopathology (25). Similarly, among children at risk for major depression, Keller and colleagues (18) found significant associations of exposure to parental psychopathology and marital discord with impaired function in children. With regard to anxiety disorders in particular, several studies involving community or pediatrically referred children have found links between anxiety disorders and low socioeconomic status (13, 15), adverse life events (43, 46), and living in a single-parent family (43).

It is noteworthy that some definitions of behavioral inhibition did show significant links to either socioeconomic status (dichotomous behavioral inhibition) or family cohesion (summary behavioral inhibition, consensus behavioral inhibition) within the comparison offspring of parents with no mood or major anxiety disorders. These results are similar to those of Fendrich et al. (47), who found that family risk factors were associated with major depression in children of nondepressed parents but not in children of depressed parents. It is possible that in the absence of parental anxiety or mood disorder, behavioral inhibition may have a different etiology that involves environmental influences. That certain genetic factors may be activated only in the presence of environmental stressors has been demonstrated by Sillaber and colleagues (48), who found that alterations in the corticotropin-releasing hormone 1 (CRH1) receptor gene in mice conferred risk for increased alcohol intake only after the mice were exposed to environmental stressors. It should be noted that family-wide factors such as socioeconomic status or family cohesion might still reflect “unshared” influences if they differentially affect children with different genetic or temperamental characteristics. That is, a child with nascent temperamental features of inhibition (or with genetic factors predisposing the child to this characteristic) may be more sensitive to certain adversity factors (e.g., low socioeconomic status, low family cohesion) and may therefore have a different response to the same stressor (e.g., withdrawing further from novelty or preserving or amplifying their inhibited style), compared with siblings without such tendencies or genes. Moreover, children in our low-risk comparison group may have been similar to the nonclinical groups in the two studies mentioned earlier that did find associations between parental behaviors and child inhibition (23, 24).

It should be underscored that etiology need not determine intervention. Since behavioral inhibition may predispose some children to social difficulties (49) or social anxiety disorders (6, 7, 9, 10, 30), it may well be that cognitive behavior methods aimed at reducing social anxiety and improving social skills may help reduce the risk conferred by behavioral inhibition. Similarly, it is possible that parental behaviors might also influence the outcome of childhood behavioral inhibition, i.e., whether the child learns to function adaptively or develops debilitating social anxiety. To draw on an example from the primate literature, Suomi (22) has demonstrated that about 20% of infant rhesus monkeys exhibit inborn profiles of inhibition in the face of novelty that are very similar to the profiles of youngsters with behavioral inhibition. A cross-fostering study, however, revealed that selectively bred high-reactive rhesus infants fostered by highly nurturant rhesus mothers left their mothers earlier, explored more, and became more socially adept, compared to high-reactive infants fostered by normal mothers and even compared to nonreactive fostered monkeys (22).

Our study should be interpreted in light of its methodological limitations. First, although we had ample power to detect medium or larger effect sizes and relative risk ratios of 2.175 or higher, we would not have been likely to detect lower effect sizes or risk ratios. Second, the factors we examined were limited to those that have been shown to have longitudinal or correlational associations with child psychopathology. Other nonshared environmental factors may yet be found to be associated with behavioral inhibition. Thus, although the measures we used have shown demonstrably robust associations with other child outcome variables (e.g., ADHD [16, 25]), it is possible that other more intensive measures of family behavior or child-parent interactions or relationship might have yielded other findings. For example, the variables we looked at would not necessarily have indexed the variables found in other studies to be associated with behavioral inhibition in toddlerhood (e.g., holding of the infant when distressed, firm limit-setting about unsafe behaviors [23], sensitivity, or “intrusiveness” [24]). In addition, it may be that other adversity measures, such as parental hostility directed toward the child (12), parental social dysfunction (50), or exposure to trauma, might have been associated with child outcome. Moreover, the exposure variables were based on retrospective reports and might have been subject to errors in recall. Longitudinal prospective studies that follow mothers from the time of the child’s birth could provide more accurate assessments of the child’s exposure to maternal psychopathology. Finally, a naturalistic family-genetic study design cannot clearly separate the effects of genetic and environmental influences, since exposure variables and severity of disorder are highly overlapping. Nonetheless, our finding that the majority of associations with exposure to maternal disorder went against the expected direction was telling. A more definitive answer to the question of whether behavioral inhibition is influenced mainly by genetic factors will require adoption studies in which both the biological and adoptive parents’ psychopathology are assessed so that genetic and environmental effects can clearly be separated.

Despite these limitations, this study suggests that several well-established environmental adversity risk factors for child psychopathology have no association with behavioral inhibition among children at high risk. Further studies are needed to confirm these results.

Received Nov. 7, 2002; revision received July 22, 2003; accepted July 25 2003. From the Pediatric Psychopharmacology Unit and Clinical Psychopharmacology Unit, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital; the Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston; and the Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts Mental Health Center and Harvard Institute of Psychiatric Epidemiology and Genetics, Boston. Address reprint requests to Dr. Hirshfeld-Becker, Pediatric Psychopharmacology Unit, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, 185 Alewife Brook Parkway, Suite 2100, Cambridge, MA 02138; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants MH-47077-05 (to Drs. Rosenbaum and Biederman) and MH-01538-02 (to Dr. Hirshfeld-Becker). The authors thank Dr. Jerome Kagan and Dr. Nancy Snidman for their contributions to this project.

Figure 1. Family Environment Scale Scores of Children With and Without Behavioral Inhibitiona

aBehavioral inhibition was assessed by using age-specific protocols that measured the child’s reaction to unfamiliar people, rooms, objects, and test procedures. Two-year-olds were categorized as inhibited if they displayed four or more fears or showed minimal vocalization or smiling, and 4- and 6-year-olds were so classified if they made fewer spontaneous comments and smiles than the lowest 20th percentile of comparison children (children of parents without mood or anxiety disorders). Associations were tested by using a generalized estimating equation model, with intrafamilial clustering controlled and parental psychopathology covaried.

Figure 2. Measures of Psychosocial Adversity for Children With and Without Behavioral Inhibitiona

aAssociations were tested by using a generalized estimating equation model, with intrafamilial clustering controlled and parental psychopathology covaried.

bSocioeconomic status refers to class (range=1–5) measured with the Hollingshead Four-Factor Index, on which higher scores indicate lower socioeconomic class.

cRutter’s factors of psychosocial adversity are low socioeconomic status, large family size, presence of family conflict, exposure to maternal psychiatric disorders, and paternal antisocial behavior.

Figure 3. Demographic Characteristics of Children With and Without Behavioral Inhibitiona

aAssociations were tested by using a generalized estimating equation model, with intrafamilial clustering controlled and parental psychopathology covaried.

bIntact family denotes that the children’s biological parents were both living with the child.

Figure 4. Rates of Behavioral Inhibition in Children With and Without Exposure to Maternal Disorders and Children With No Maternal Disordersa

aAssociations were tested by using a generalized estimating equation model, with intrafamilial clustering controlled and socioeconomic status covaried.

bSignificant difference from no-maternal-disorder group (p<0.05).

1. Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N: Biological bases of childhood shyness. Science 1988; 240:167–171Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Kagan J, Snidman N, Friedman D, Nineberg A, Gallery DJ, Faraone SV: A controlled study of behavioral inhibition in children of parents with panic disorder and depression. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:2002–2010Link, Google Scholar

3. Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Gersten M, Hirshfeld DR, Meminger SR, Herman JB, Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N: Behavioral inhibition in children of parents with panic disorder and agoraphobia: a controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:463–470Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Manassis K, Bradley S, Goldberg S, Hood J, Swinson RP: Behavioural inhibition, attachment and anxiety in children of mothers with anxiety disorders. Can J Psychiatry 1995; 40:87–92Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Battaglia M, Bajo S, Strambi LF, Brambilla F, Castronovo C, Vanni G, Bellodi L: Physiological and behavioral responses to minor stressors in offspring of patients with panic disorder. J Psychiatr Res 1997; 31:365–376Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Biederman J, Rosenbaum JF, Hirshfeld DR, Faraone SV, Bolduc EA, Gersten M, Meminger SR, Kagan J, Snidman N, Reznick JS: Psychiatric correlates of behavioral inhibition in young children of parents with and without psychiatric disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:21–26Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Biederman J, Rosenbaum JF, Bolduc-Murphy EA, Faraone SV, Chaloff J, Hirshfeld DR, Kagan J: A 3-year follow-up of children with and without behavioral inhibition. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1993; 32:814–821Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Hirshfeld DR, Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Bolduc EA, Faraone SV, Snidman N, Reznick JS, Kagan J: Stable behavioral inhibition and its association with anxiety disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31:103–111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Hayward C, Killen JD, Kraemer HC, Taylor CB: Linking self-reported childhood behavioral inhibition to adolescent social phobia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37:1308–1316Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Schwartz C, Snidman N, Kagan J: Adolescent social anxiety as an outcome of inhibited temperament in childhood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:1008–1015Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Rutter M, Quinton D: Psychiatric disorder: ecological factors and concepts of causation, in Ecological Factors in Human Development. Edited by McGurk H. Amsterdam, North Holland, 1977, pp 173–187Google Scholar

12. Rutter M, Quinton D: Parental psychiatric disorder: effects on children. Psychol Med 1984; 14:853–880Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Bird HR, Gould MS, Yager T, Staghezza B, Canino G: Risk factors for maladjustment in Puerto Rican children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1989; 28:847–850Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Blantz B, Schmidt M, Esser G: Familial adversities and child psychiatric disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatr Disord 1991; 32:939–950Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Velez CN, Johnson J, Cohen P: A longitudinal analysis of selected risk factors for childhood psychopathology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1989; 28:861–864Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Biederman J, Milberger S, Faraone SV, Kiely K, Guite J, Mick E, Ablon S, Warburton R, Reed E: Family-environment risk factors for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a test of Rutter’s indicators of adversity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:464–470Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Biederman J, Faraone SV, Monuteaux MC: Differential effect of environmental adversity by gender: Rutter’s index of adversity in a group of boys and girls with and without ADHD. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1556–1562Link, Google Scholar

18. Keller MB, Beardslee WR, Dorer DJ, Lavori PW, Samuelson H, Klerman GR: Impact of severity and chronicity of parental affective illness on adaptive functioning and psychopathology in children. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:930–937Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Rosenblum LA, Coplan JD, Friedman S, Bassoff T, Gorman JM, Andrews MW: Adverse early experiences affect noradrenergic and serotonergic functioning in adult primates. Biol Psychiatry 1994; 35:221–227Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Suomi SJ, Kraemer GW, Baysinger CM, DeLizio RD: Inherited and experiential factors associated with individual differences in anxious behavior displayed by rhesus monkeys, in Anxiety: New Research and Changing Concepts. Edited by Klein DF, Rabkin J. New York, Raven Press, 1981, pp 179–200Google Scholar

21. Suomi SJ: Anxiety-like disorders in young nonhuman primates, in Anxiety Disorders of Childhood. Edited by Gittelman R. New York, Guilford, 1986, pp 1–23Google Scholar

22. Suomi SJ: Early determinants of behaviour: evidence from primate studies. Br Med Bull 1997; 53:170–184Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Arcus DM: The Experiential Modification of Temperamental Bias in Inhibited and Uninhibited Children. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1991Google Scholar

24. Belsky J, Hsieh K-H, Crnic K: Mothering, fathering, and infant negativity as antecedents of boys’ externalizing problems and inhibition at age 3 years: differential susceptibility to rearing experience? Dev Psychopathol 1998; 10:301–319Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Biederman J, Milberger S, Faraone SV, Kiely K, Guite J, Mick E, Ablon JS, Warburton R, Reed E, Davis SG: Impact of adversity on functioning and comorbidity in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:1495–1503Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Robinson JL, Kagan J, Reznick JS, Corley RP: The heritability of inhibited and uninhibited behavior: a twin study. Dev Psychol 1992; 28:1030–1037Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Kerr M, Lambert WW, Stattin H, Klackenberg-Larsson I: Stability of inhibition in a Swedish longitudinal sample. Child Dev 1994; 65:138–146Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Broberg A, Lamb M, Hwang P: Inhibition: its stability and correlates in sixteen- to forty-month-old children. Child Dev 1990; 61:1153–1163Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Chen X, Hastings PD, Rubin KH, Chen H, Cen G, Stewart SL: Child-rearing attitudes and behavioral inhibition in Chinese and Canadian toddlers: a cross-cultural study. Dev Psychol 1998; 34:677–686Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Rosenbaum JF, Hérot C, Friedman D, Snidman N, Kagan J, Faraone SV: Further evidence of association between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1673–1679Link, Google Scholar

31. Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Bolduc EA, Hirshfeld DR, Faraone SV, Kagan J: Comorbidity of parental anxiety disorders as risk for child-onset anxiety in inhibited children. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:475–481Link, Google Scholar

32. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Non-Patient Edition (SCID-NP, Version 1.0). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

33. Moos RH, Moos BS: Manual for the Family Environment Scale. Palo Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1974Google Scholar

34. Moos RH, Moos BS: A typology of family environments. Fam Proc 1976; 15:357–372Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Hollingshead AB: Four-Factor Index of Social Status. New Haven, Conn, Yale University, Department of Sociology, 1975Google Scholar

36. Liang KY, Zeger SL: Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 1986; 73:13–22Crossref, Google Scholar

37. Stata Reference Manual: Release 5.0. College Station, Tex, Stata Corp, 1997Google Scholar

38. Emde RN, Plomin R, Robinson JA, Corley R, DeFries J, Fulker DW, Reznick JS, Campos J, Kagan J, Zahn-Waxler C: Temperament, emotion, and cognition at fourteen months: the MacArthur Longitudinal Twin Study. Child Dev 1992; 63:1437–1455Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Matheny AP Jr: Children’s behavioral inhibition over age and across situations: genetic similarity for a trait during change. J Pers 1989; 57:215–235Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. DiLalla LF, Kagan J, Reznick JS: Genetic etiology of behavioral inhibition among 2-year-old children. Infant Behavioral Development 1994; 17:405–412Crossref, Google Scholar

41. Plomin R, Emde RN, Braungart JM, Campos J, Corley R, Fulker DW, Kagan J, Reznick JS, Robinson J, Zahn-Waxler C, et al: Genetic change and continuity from fourteen to twenty months: the MacArthur Longitudinal Twin Study. Child Dev 1993; 64:1354–1376Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Plomin R: Development, Genetics, and Psychology. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1986Google Scholar

43. Kroes M, Kalff AC, Steyaert J, Kessels AG, Feron FJ, Hendriksen JG, van Zeben TM, Troost J, Jolles J, Vles JS: A longitudinal community study: do psychosocial risk factors and Child Behavior Checklist scores at 5 years of age predict psychiatric diagnoses at a later age? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41:955–963Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Graham P, Rutter M: Psychiatric disorder in the young adolescent: a follow-up study. Proc R Soc Med 1973; 66:1226–1228Medline, Google Scholar

45. Offord DR, Boyle MH, Racine YA, Fleming JE, Cadman DT, Blum HM, Byrne C, Links PS, Lipman EL, MacMillan HL, et al: Outcome, prognosis, and risk in a longitudinal follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31:916–923Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Costello EJ, Costello AJ, Edelbrock C, Burns BJ, Dulcan MK, Brent D, Janiszewski S: Psychiatric disorders in pediatric primary care: prevalence and risk factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:1107–1116Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Fendrich M, Warner V, Weissman MM: Family risk factors, parental depression, and psychopathology in offspring. Dev Psychol 1990; 26:40–50Crossref, Google Scholar

48. Sillaber I, Rammes G, Zimmermann S, Mahal B, Zieglgansberger W, Wurst W, Holsboer F, Spanagel R: Enhanced and delayed stress-induced alcohol drinking in mice lacking functional CRH1 receptors. Science 2002; 296:931–933Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Asendorpf J: The malleability of behavioral inhibition: a study of individual developmental functions. Dev Psychol 1994; 30:912–919Crossref, Google Scholar

50. Mufson L, Aidala A, Warner V: Social dysfunction and psychiatric disorder in mothers and their children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 33:1256–1264Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar