A Controlled Study of Behavioral Inhibition in Children of Parents With Panic Disorder and Depression

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: “Behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar” has been proposed as a precursor to anxiety disorders. Children with behavioral inhibition are cautious, quiet, introverted, and shy in unfamiliar situations. Several lines of evidence suggest that behavioral inhibition is an index of anxiety proneness. The authors sought to replicate prior findings and examine the specificity of the association between behavioral inhibition and anxiety. METHOD: Laboratory-based behavioral observations were used to assess behavioral inhibition in 129 young children of parents with panic disorder and major depression, 22 children of parents with panic disorder without major depression, 49 children of parents with major depression without panic disorder, and 84 children of parents without anxiety disorders or major depression (comparison group). A standard definition of behavioral inhibition based on previous research (“dichotomous behavioral inhibition”) was compared with two other definitions. RESULTS: Dichotomous behavioral inhibition was most frequent among the children of parents with panic disorder plus major depression (29% versus 12% in comparison subjects). For all definitions, the univariate effects of parental major depression were significant (conferring a twofold risk for behavioral inhibition), and for most definitions the effects of parental panic disorder conferred a twofold risk as well. CONCLUSIONS: These results suggest that the comorbidity of panic disorder and major depression accounts for much of the observed familial link between parental panic disorder and childhood behavioral inhibition. Further work is needed to elucidate the role of parental major depression in conferring risk for behavioral inhibition in children.

It has been proposed that “behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar” (1) is an early temperamental precursor of later anxiety disorders (2–4). This temperamental construct, which can be measured in a laboratory setting, reflects the consistent tendency to display fear and withdrawal in situations that are novel or unfamiliar. Since these responses are assumed to indicate low thresholds of limbic arousal or increased sympathetic outflow in response to challenge, they may indicate a predisposition to develop anxiety disorders that can be measured long before the disorders can be assessed with a standard psychiatric instrument. Children with behavioral inhibition are easily aroused to motor activity and distress as infants, shy and fearful as toddlers, shy with strangers and timid in unfamiliar situations as preschoolers, and cautious, quiet, and introverted at school age (1).

Descriptions of inhibited school-age children are similar to clinical descriptions of children whose parents have panic disorder and to retrospective descriptions of childhood by adults with panic disorder or agoraphobia (5–12). For example, inhibited children show school refusal and separation anxiety (13). These features, along with evidence of increased arousal in the limbic-sympathetic axes (14–16), fit well with hypotheses about the underpinnings of anxiety disorders, particularly panic disorder (17–21).

Although it is well known that children of parents with panic disorder are at high risk for anxiety disorders (22–24), most of these children will not develop disorders. In contrast, because behavioral inhibition can be measured in young children and is believed to reflect a predisposition to anxiety disorders, it may provide a clinically useful means of better identifying the children most likely to benefit from programs aimed at prevention of anxiety disorders (for very young children) or early intervention (for older children who may already show some signs of anxiety disorder).

Family studies of anxiety disorders suggest that behavioral inhibition is an index of anxiety proneness. In a pilot study (25), we found behavioral inhibition to be more prevalent among 33 children of patients with panic disorder (with or without comorbid major depression) than among 23 children who were relatives of psychiatric comparison subjects. Another group of investigators (26) found that 65% of 20 children of a heterogeneous group of anxious parents had behavioral inhibition, and a third group (27) showed that 19 children of parents with panic disorder exhibited more inhibited behaviors than did 16 children of comparison parents. Although promising, these results can only be viewed as preliminary because of the small numbers of subjects in the studies, the absence of nonclinical comparison groups (in all but one), and the lack of attention in the studies by other groups to effects of comorbid major depression in the anxious parents. They require further replication with larger groups of subjects.

Therefore, in the present study we sought to replicate and extend these prior findings by 1) using a much larger group of subjects, 2) including a nonclinical comparison group, 3) examining the specificity of the association between behavioral inhibition and anxiety by assessing the effects of parental depression, and 4) examining the predictive validity of different definitions of behavioral inhibition.

We hypothesized that behavioral inhibition would be more prevalent among children of parents with panic disorder (with or without comorbid depression) than among children of nonclinical comparison parents. We included a small group of children of parents with major depression in order to explore whether children of parents with major depression also have higher rates of behavioral inhibition than children of nonclinical comparison parents.

Method

Subjects

We recruited three groups of parents who had at least one child in the proper age range to be assessed for behavioral inhibition according to established age-specific protocols (age=2–6 years). The first group comprised 131 parents being treated for panic disorder and their 227 children; 102 of these parents and an additional 11 of their spouses had had at least one episode of major depression. The second group consisted of 61 comparison parents with neither major anxiety syndromes (panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, or obsessive-compulsive disorder [OCD]) nor mood disorders and their 119 children. Third were 39 parents being treated for major depression who did not have a history of either panic disorder or agoraphobia and their 67 children. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Massachusetts General Hospital. The parents provided written informed consent for themselves and their children. The children assented to the study procedures in writing. As an incentive, we offered the subjects a modest stipend for completing the assessments.

We recruited parents with panic disorder and major depression from clinical referrals and advertising. Only patients who received a positive lifetime diagnosis of panic disorder or major depression and who had been treated for these disorders were included. We recruited comparison subjects from hospital personnel and through community advertisements calling for healthy adults with young children. Potential comparison subjects were included only if they and their spouses did not meet the DSM-III-R criteria for lifetime panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, OCD, bipolar disorder, bipolar II disorder, depression, or dysthymia. We did not use either posttraumatic stress disorder or simple phobia as an exclusion for the comparison subjects, but the rates of these disorders in the comparison subjects were low (1% and 5%, respectively). Subjects who would not cooperate, could not understand, or could not communicate sufficiently were excluded, as were families containing a parent who had a psychotic disorder, a parent who was suicidal, or a child or parent who was mentally retarded.

Diagnostic Assessments of Parents

To assure blindness, 1) only the project coordinator knew the ascertainment group of the parent, 2) the staff assessing behavioral inhibition were blind to all other data, and 3) the psychiatric interviewers were blind to ascertainment status (e.g., panic disorder, depression, comparison, spouse) and the behavioral inhibition classification of the children.

The parents were interviewed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (28). We made every effort to interview both parents from each family, regardless of marital status. Complete diagnostic interviews were available for 229 mothers (including all divorced mothers) and 221 fathers (including 39 of the 43 divorced fathers). Social class was assessed with the Hollingshead Four-Factor Index of Social Status (29). Based on 173 interviews, the kappa coefficients of agreement between the six study interviewers and three board-certified psychiatrists (who listened to audiotaped interviews made by the raters) were 0.86 for major depression, 0.96 for panic disorder, 0.90 for agoraphobia, 0.83 for social phobia, 0.84 for simple phobia, and 0.83 for generalized anxiety disorder.

All subjects were diagnosed on the basis of a consensus judgment by two board-certified psychiatrists (J.B. and J.F.R.) who used information gathered with the structured interviews and from medical records when they were available. In cases of diagnostic uncertainties, this review included examination of the audiotape of the interview. The diagnosticians were blind to the subject’s recruitment group, to all nonpsychiatric data collected from the individual being diagnosed, and to all information about other family members.

Assessment of Behavioral Inhibition

From the pool of 413 children at risk, all of the children aged 2 to 6 years (N=284) were assessed for behavioral inhibition. The behavioral inhibition assessments measured the child’s reaction to unfamiliar events—primarily people, rooms, objects, and test procedures (Appendix 1). The children’s behaviors in these situations were observed and rated as described in Table 1.

The criteria for classification of behavioral inhibition according to the three definitions used are presented in Table 2. Prior work (1) had shown that the displays of distress and/or avoidance in response to unfamiliar people or events—signs of fear—were a sensitive index of behavioral inhibition at 2 years of age. Therefore, children 2 years old were categorized as inhibited if they displayed four or more fears or were rated as having minimal vocalizations or minimal smiles. For 4-year-old and 6-year-old children, the number of spontaneous comments made to the unfamiliar examiner and the number of spontaneous smiles over the 60-minute battery were used because they have proven to be sensitive indexes of behavioral inhibition (1). Because behavioral inhibition has an estimated prevalence of 10% to 20% in this age range, the numbers of comments and smiles that defined the lowest 20th percentile of the comparison children were set as the criteria for behavioral inhibition. Thus, 4-year-old children who made eight or fewer spontaneous comments and had six or fewer smiles were classified as behaviorally inhibited. Six-year-old children who made four or fewer spontaneous comments and had eight or fewer smiles were classified as behaviorally inhibited. We call this index “dichotomous behavioral inhibition.” The intraclass correlation indicating interrater reliability of the coding of smiles was 0.96, and the correlation for spontaneous comments was 1.00.

A second, related index of behavioral inhibition was a 4-point global rating made by one of the authors (J.K.) on the basis of the child’s behavior across the entire laboratory battery. A rating of 1 reflected the most uninhibited behavior, and a rating of 4 indicated extremely inhibited behavior. The kappa value for the reliability of the 4-point rating, according to an independent coding of a random sample of 47 children, was 0.70. Children who received ratings of 3 or 4 were considered inhibited. We call this index “global behavioral inhibition.” This index was determined for only the 4-year-olds and 6-year-olds.

In addition, all of the other behavioral variables assessed for each age group were used to create a third index, called the “behavioral inhibition summary score.” The score was derived from a principal-factors factor analysis (with varimax rotation) of all the behavioral variables listed in Table 1(30). The factor analyses were computed separately for the 2-year-old, 4-year-old, and 6-year-old children. We retained factors having eigenvalues greater than 1 and selected for each age group the factor that best reflected behavioral inhibition. For these factors, we computed factor scores that served as the summary variables. These factor analyses were done to compute a summary score that condensed many behavioral inhibition measures into a single variable; the analyses were not used to define and validate the underlying factor structure of behavioral inhibition, since a much larger group of subjects would be needed for that purpose.

In the factor analysis used to derive the summary behavioral inhibition measure, two factors were retained for the 2-year-olds, and they explained 100% of the variance for the variables coded for the 2-year-olds listed in Table 1. The first factor had a moderate loading for distress displays (0.39) and high loadings for resistance to having electrodes and a blood pressure cuff applied (0.89) and for distractibility (0.89). The second factor clearly measured the inverse of behavioral inhibition, as indicated by high loadings for vocalization (0.60) and smiling (0.69) and a low loading for avoidance displays (–0.50). Thus, the second factor, reversed, was used for the behavioral inhibition summary score for this age group.

Two factors were retained for the 4-year-olds, and they explained 90% of the variance for the variables listed for the 4-year-olds in Table 1. The first factor clearly measured behavioral inhibition, with negative loadings for smiles (–0.41) and spontaneous comments (–0.62) and positive loadings for shyness (0.82), fear (0.42), voice quality (0.83), and reluctance to play with toys in the risk room with (0.43) and without (0.40) the examiner present, and it was used as the behavioral inhibition summary score. The second factor reflected resistance to having electrodes (0.76) and a blood pressure cuff (0.67) applied and may indicate oppositionality.

Two similar factors, explaining 91% of the variance in the variables listed in Table 1, were retained for the 6-year-olds. The first factor had low loadings for smiles (–0.36) and spontaneous comments (–0.47) and high loadings for shyness (0.88) and fear (0.43), and it clearly constituted the behavioral inhibition summary score. The second reflected resistance to having a blood pressure cuff (0.79) and electrodes (0.84) applied.

To classify the children on the basis of this summary score, the children in each age group who had higher behavioral inhibition summary scores than 80% of the comparison children in their age range (i.e., children in the highest 20th percentile of inhibition) were classified as behaviorally inhibited. We called this classification “summary behavioral inhibition.”

Data Analyses

The data analyses were designed to accommodate two features of our data. First, as in epidemiologic studies of panic disorder (31, 32), many of the panic disorder patients in this study also had major depression. Second, some of the panic disorder probands had spouses with major depression. Thus, we analyzed the data by using logistic (33) and ordinal regression procedures that modeled behavioral inhibition outcomes as a function of parental panic disorder (i.e., one or both parents had panic disorder) and parental depression (i.e., one or both parents had major depression). We used the 0.05, two-tailed alpha level to determine statistical significance.

To determine whether demographic variables confounded our tests of the effects of panic disorder and major depression, we followed the guidelines of Weinberg (34) by using the following approach. First, we classified a demographic variable as a potential confound if logistic or ordinal regression showed it to be significantly associated with parental panic disorder or parental major depression and with behavioral inhibition in the child (i.e., with both the predictor and outcome variables). Second, if a variable was shown to be a potential confound, we used it as a covariate in the logistic and ordinal regression models used to assess the link between parental diagnoses and child outcomes.

Multiple members of a single family (i.e., multiple siblings) cannot be considered independently sampled because they share genetic, cultural, and social risk factors. To deal with this problem, for all comparisons we used the generalized estimating equation method to estimate regression models (35, 36), controlling for one or more potentially confounding variables where necessary, as implemented in Stata statistical software (37). Unlike standard linear or logistic regression models, generalized estimating equation models take into account the nonindependence of observations. Thus, unlike standard methods, they produce accurate p values in the presence of intrafamilial clustering. We chose specific models to conform to the distribution of the variable: we used the binomial family and a logit link for binary outcomes, the Gaussian family and identity link for normally distributed outcomes, and the Poisson family and log link for ordinal outcomes. We used Wald’s test to assess the statistical significance of individual regressors.

Results

This analysis was limited to the 284 children who were between the ages of 2 years and 6 years and who were therefore of appropriate age to be assessed for behavioral inhibition. These included 129 children from 102 families in which the parents had both panic disorder and major depression, 22 children from 17 families in which one or both parents had panic disorder without major depression, 49 children from 37 families in which one or both parents had major depression without panic disorder, and 84 children from 60 families in which neither parent had either depression or a major anxiety disorder (comparison group).

Table 3 shows demographic variables for the four different parental diagnostic groups and indicates the significance of the association of these variables with parental panic disorder and major depression. Social class was associated with both major depression (significantly) and panic disorder (nonsignificantly) in parents, family intactness was associated with major depression in parents (significantly), and race/ethnicity was associated with panic disorder in parents (nonsignificantly). Of these variables, only social class was significantly associated with behavioral inhibition. For all definitions of behavioral inhibition, lower social class predicted behavioral inhibition, significantly for dichotomous and summary behavioral inhibition (generalized estimating equation, p<0.05) and marginally for global behavioral inhibition (p=0.08). The odds ratios (and 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) were 1.4 (95% CI=1.0–1.8), 1.3 (95% CI=1.0–1.6), and 1.3 (95% CI=1.0–1.7), respectively. Therefore, we statistically controlled our analyses for social class as described in the Method section.

Dichotomous Behavioral Inhibition

Using a generalized estimating equation model that covaried social class, we found that parental major depression was a small but significant predictor of behavioral inhibition in the children (odds ratio=2.0, 95% CI=1.0–3.7, z=2.06, p=0.04). Parental panic disorder predicted dichotomous behavioral inhibition in the univariate comparison (odds ratio=1.9, 95% CI=1.1–3.3, z=2.14, p=0.04), but this effect lost significance after we controlled for social class (odds ratio=1.7, 95% CI=1.0–3.1, z=1.85, p<0.07).

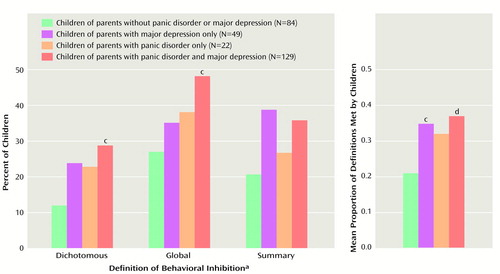

Given the well-known comorbidity of panic disorder and major depression, Figure 1 illustrates the joint effects of these disorders by separating the children by parental diagnosis, into those not exposed to familial risk for either disorder, those at risk for panic disorder but not major depression, those at risk for major depression but not panic disorder, and those at risk for both disorders. As Figure 1 shows, we found the largest proportion of children with dichotomous behavioral inhibition in the families in which one or both parents had panic disorder plus major depression. The four-group comparison was statistically significant (χ2=12.37, df=4, p=0.02). The only statistically significant pairwise comparison for this definition was between the group with parental panic disorder plus major depression and the comparison group (odds ratio=2.6, 95% CI=1.2–5.6, z=2.44, p=0.02).

Global Behavioral Inhibition

We found a small but significant effect on global behavioral inhibition from parental panic disorder (odds ratio=1.9, 95% CI=1.1–3.4, z=2.29, p=0.03, by logistic regression with social class as a covariate). The effect of major depression was in the univariate comparison (odds ratio=1.9, 95% CI=1.1–3.3, z=2.16, p=0.04) but dropped to marginal significance when social class was covaried (odds ratio=1.7, 95% CI=1.0–3.1, z=1.86, p<0.07). As seen in Figure 1, when we classified families to account for comorbidity, the four-group comparison was statistically significant (χ2=9.29, df=4, p=0.05). The only statistically significant pairwise comparison was between the group with parental panic disorder plus major depression and the comparison group (odds ratio=2.2, 95% CI=1.1–4.2, z=2.28, p<0.09).

Summary Behavioral Inhibition

Using summary behavioral inhibition as our definition and covarying for socioeconomic status, we found small but significant effects of parental major depression (odds ratio=1.8, 95% CI=1.1–3.2, z=2.19, p=0.03) but not parental panic disorder (odds ratio=1.3, 95% CI=0.8–2.2, z=0.96, p=0.33). When we classified families to account for comorbidity (Figure 1), no comparison achieved significance (χ2=8.74, df=4, p=0.07).

Proportion of Behavioral Inhibition Definitions Met

In order to identify the children who were most clearly inhibited, we counted the number of behavioral inhibition definitions each child satisfied. Since the children in the different age groups had different total numbers of definitions they could satisfy (maximum of two for 2-year-olds and three for 4–6-year-olds), we calculated the proportion of definitions each child met. Using a generalized estimating equation ordered regression model that covaried social class, we found a small but significant effect on the proportion of definitions met for parental major depression (z=2.46, p=0.02). The effect of parental panic disorder on the proportion of behavioral inhibition definitions met was significant in the univariate comparison (z=2.18, p=0.03) but dropped to marginal significance when social class was covaried (z=1.89, p<0.06).

In addition, as seen in Figure 1, when we classified families to account for parental comorbidity of panic disorder and major depression, we found the largest proportion of definitions met among the children in the groups with parental panic disorder plus major depression and with major depression only (χ2=15.07, df=4, p=0.005), and both of these groups differed significantly from the children of the comparison parents (panic disorder plus major depression: z=2.66, p=0.008; major depression: z=2.21, p=0.03). The difference between the children of the parents with panic disorder and the comparison subjects was only marginally significant (z=1.67, p=0.09).

Discussion

The current work confirms and extends prior findings suggesting that children whose parents have both panic disorder and major depression may be particularly at risk for behavioral inhibition. Our dichotomous measure of behavioral inhibition, which was based on the degree to which the child smiled and made spontaneous comments or exhibited fears during the laboratory battery, showed significant univariate effects for both parental major depression and panic disorder. Moreover, it showed that children whose parents had both panic disorder and major depression had significantly higher rates of behavioral inhibition than comparison subjects, whereas children whose parents had either disorder alone had intermediate rates of behavioral inhibition not distinguishable from the rates of the comparison subjects or the children whose parents had both disorders. These results suggest that the comorbidity of panic disorder and major depression accounts for much of the observed familial link between parental panic disorder and childhood behavioral inhibition. The proportion of cases of behavioral inhibition attributable to parental panic disorder plus major depression (that is, the attributable risk percent, or the probability that a child developed behavioral inhibition as a result of parental panic disorder plus major depression) was 59%.

In addition to a dichotomous definition of behavioral inhibition based on smiles, spontaneous comments, or exhibited fears, we also examined three other indices of behavioral inhibition: global behavioral inhibition, derived from a global impression of the child’s inhibition; summary behavioral inhibition, derived from a factor analysis of all of the behavior variables rated during the assessment; and the proportion of the behavioral inhibition definitions met by the child. Each of these definitions showed a significant univariate effect of major depression, and all but summary behavioral inhibition also showed a significant univariate effect of panic disorder. That the effects of panic disorder on dichotomous behavioral inhibition and on the proportion of behavioral inhibition definitions met were reduced to marginal significance when social class was covaried may be due to the fact that none of the families with panic disorder (but no major depression) was below socioeconomic status class II. Thus, it is possible that the excess of behavioral inhibition in lower-class families may have operated to reduce the effect of panic disorder. When the analyses were limited to families from social classes I and II (the two highest classes), the effect of panic disorder became significant for dichotomous behavioral inhibition (odds ratio=2.0, 95% CI=1.0–4.1, z=1.97, p=0.05), summary behavioral inhibition (odds ratio=1.8, 95% CI=1.0–3.3, z=2.05, p=0.04), and proportion of definitions met (z=2.53, p=0.02).

Notably, the higher concentration of behavioral inhibition among the children whose parents had both panic disorder and major depression was evident across all measures of behavioral inhibition. In fact, our analyses suggest that it is the comorbid group that accounts for our finding that panic disorder and major depression in parents predict behavioral inhibition in children. The proportions of cases of global and summary behavioral inhibition attributable to parental panic disorder plus major depression were 44% and 42%, respectively. But our conclusions about children of parents who have panic disorder (with no major depression) or major depression (with no panic disorder) are limited by the small size of the depression and panic disorder groups. Moreover, the extensive comorbidity of these disorders highlights how difficult it is to assess the implications of one of these disorders without also assessing the other. Future work with more subjects is needed to determine whether the children from the noncomorbid groups have a significantly greater risk for behavioral inhibition than do the children at risk for neither disorder.

It is, however, unlikely that larger groups of subjects will show clinically meaningful differences in the prevalence of childhood behavioral inhibition between the depression-only and panic-only groups. We found that they were very similar to one another for dichotomous behavioral inhibition (24% versus 23%), global behavioral inhibition (35% versus 38%), and the proportion of behavioral inhibition definitions met (0.35 versus 0.32). Thus, the differences in risk for behavioral inhibition afforded by major depression and panic disorder may not be clinically significant even if they are eventually shown to be statistically significant in larger groups of subjects.

The finding that many parents ascertained for panic disorder also had major depression is consistent with the substantial evidence for extensive comorbidity of these two disorders (31, 32, 38). Moreover, a history of childhood anxiety disorders among adults with panic disorder appears to confer vulnerability to comorbid depression (12), and twin studies suggest etiologic links between the two disorders (39, 40).

The high rates of behavioral inhibition among children of parents with both disorders is consistent with a multifactorial model that views panic disorder plus major depression as a relatively severe condition arising from the same pool of etiologic factors that cause the milder, individual disorders. Under this model, children at risk for both disorders would be exposed to a stronger dose of familial risk factors and thus would show more evidence for outcomes, such as behavioral inhibition, associated with that risk. This view of panic disorder plus major depression is consistent with clinical data. A recent literature review (41) showed that patients with both disorders usually have more severe symptoms, earlier treatment, more frequent hospitalizations, a greater risk for suicide, and worse outcomes.

Although our data suggest that behavioral inhibition reflects the familial predisposition to major depression and panic disorder, we cannot determine whether behavioral inhibition is a genetically transmitted trait or whether its transmission in families is due to cultural transmission, social learning, or pathogenic child-rearing practices. We know from twin studies (42–44) that behavioral inhibition does have a significant, but not exclusive, genetic contribution. Clearly, further work is needed to clarify the respective roles of nature and nurture in the transmission of this trait.

Even if behavioral inhibition does mark a predisposition to major depression and panic disorder, we need longitudinal data to show that it predicts subsequent illness. The only studies addressing this issue prospectively were our pilot studies (45, 46). These showed that baseline behavioral inhibition predicted multiple anxiety disorders, avoidant disorder, separation anxiety disorder, and agoraphobia at follow-up. Notably, the rates of illness were greatest among children who were consistently inhibited at assessments from 21 months to 7 years. These results support the idea that behavioral inhibition is a predictor of subsequent anxiety disorders.

The results of the present study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Our statistical power to examine the effects of noncomorbid panic disorder and major depression was low, as was our power to detect effects for each age group. Moreover, because most of our effects were small, it is likely that more accurate measures of behavioral inhibition will be needed to make our results clinically significant. Our proband parents were clinically referred, limiting the generalizability of our findings. It is possible that anxious and depressed parents with shy children were more likely to participate in our study than anxious or depressed parents without shy children. If so, the rates of behavioral inhibition in these groups might be exaggerated, but the group differences would not be confounded because any bias toward recruiting parents with shy children should apply equally to comparison subjects. We did not assess parents to determine whether they had had behavioral inhibition as children. Future work would benefit from such assessments to determine whether a parental history of behavioral inhibition accounts for the observed link of panic disorder and major depression in parents to behavioral inhibition in children.

Despite these considerations, we found that parental panic disorder and major depression confer a significant risk for behavioral inhibition in children. Further longitudinal follow-up of these subjects is needed to determine whether this trait will confer vulnerability to psychopathology among these children. Other studies are needed to further explore the specificity of the association of childhood behavioral inhibition with anxiety disorders and depression and to determine whether behavioral inhibition will be a useful marker for choosing children for primary prevention or early intervention protocols.

|

|

|

Received Jan. 11, 2000; revision received June 16, 2000; accepted July 12, 2000. From the Clinical Psychopharmacology Unit and the Pediatric Psychopharmacology Unit, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital; the Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston; and the Department of Psychology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Address reprint requests to Dr. Rosenbaum, Clinical Psychopharmacology Unit, WACC 812, Massachusetts General Hospital, 15 Parkman St., Boston, MA 02114; jrosenbaum@ partners.org. Supported by NIMH grants MH-47077 (to Drs. Rosenbaum and Biederman) and MH-01538 (to Dr. Hirshfeld-Becker).

Figure 1. Behavioral Inhibition in 2-, 4-, and 6-Year-Old Children of Parents With Panic Disorder, Depression, Both, or Neither, by Definition of Behavioral Inhibitiona and Number of Definitions Metb

aThe dichotomous measure of behavioral inhibition was based on the degree to which the child smiled, made spontaneous comments, or exhibited fears during the laboratory battery. Global behavioral inhibition was derived from a global impression of the child’s inhibition. Summary behavioral inhibition was derived from a factor analysis of all of the behavior variables rated during the assessment. Global behavioral inhibition was rated for only the 4- and 6-year-olds, and the numbers of children were as follows: no panic disorder or major depression, N=73; major depression only, N=40; panic disorder only, N=16; panic disorder plus major depression, N=103.

bAssociations were tested by using a generalized estimating equation model comparing the three diagnostic groups and the nonclinical comparison subjects (df=3) for their effect on behavioral inhibition, with covariance for socioeconomic status (df=1) and control for intrafamilial clustering (total df=4).

cSignificantly different from the comparison group (p<0.05).

dSignificantly different from the comparison group (p<0.01).

1. Kagan J: Galen’s Prophecy. New York, Basic Books, 1994Google Scholar

2. Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Hirshfeld DR, Bolduc EA, Chaloff J: Behavioral inhibition in children: a possible precursor to panic disorder or social phobia. J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52:5–9Medline, Google Scholar

3. Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Bolduc EA, Hirshfeld DR, Faraone SV, Kagan J: Comorbidity of parental anxiety disorders as risk for childhood-onset anxiety in inhibited children. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:475–481Link, Google Scholar

4. Rosenbaum J, Biederman J, Bolduc-Murphy E, Faraone S, Chaloff J, Hirshfeld D, Kagan J: Behavioral inhibition in childhood: a risk factor for anxiety disorders. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1993; 1:2–16Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Klein D: Delineation of two drug-responsive anxiety syndromes. Psychopharmacologia 1964; 5:397–408Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Berg I, Marks I, McGuire R, Lipsedge M: School phobia and agoraphobia. Psychol Med 1974; 4:428–434Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Berg I: School phobia in the children of agoraphobic women. Br J Psychiatry 1976; 128:86–89Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Deltito JA, Perugi G, Maremmani I, Mignani V, Cassano GB: The importance of separation anxiety in the differentiation of panic disorder from agoraphobia. Psychiatr Dev 1986; 4:227–236Medline, Google Scholar

9. Aronson TA, Logue CM: On the longitudinal course of panic disorder: development history and predictors of phobic complications. Compr Psychiatry 1987; 28:344–355Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Lipsitz JD, Martin LY, Mannuzza S, Chapman TF, Liebowitz MR, Klein DF, Fyer AJ: Childhood separation anxiety disorder in patients with adult anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:927–929Link, Google Scholar

11. Otto MW, Pollack MH, Rosenbaum JF, Sachs GS, Asher RH: Childhood history of anxiety in adults with panic disorder: association with anxiety sensitivity and comorbidity. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1994; 1:288–293Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Pollack MH, Otto MW, Sabatino S, Majcher D, Worthington JJ, McArdle ET, Rosenbaum JF: Relationship of childhood anxiety to adult panic disorder: correlates and influence on course. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:376–381Link, Google Scholar

13. Gersten M: Behavioral inhibition in the classroom, in Perspectives on Behavioral Inhibition. Edited by Reznick JS. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1989, pp 71–91Google Scholar

14. Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N: The physiology and psychology of behavioral inhibition in children. Child Dev 1987; 58:1459–1473Google Scholar

15. Snidman N: Behavioral inhibition and sympathetic influence on the cardiovascular system, in Perspectives on Behavioral Inhibition. Edited by Reznick JS. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1989, pp 51–70Google Scholar

16. Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N, Johnson MO, Gibbons JL, Gersten M, Biederman J, Rosenbaum JF: Origins of panic disorder, in Neurobiology of Panic Disorder: Frontiers of Clinical Neuroscience, vol 8. Edited by Ballenger JC. New York, Wiley-Liss, 1990, pp 81–87Google Scholar

17. Charney DS, Redmond DE Jr: Neurobiological mechanisms in human anxiety: evidence supporting central noradrenergic hyperactivity. Neuropharmacology 1983; 22:1531–1536Google Scholar

18. Reiman EM, Raichle ME, Butler FK, Herscovitch P, Robins E: A focal brain abnormality in panic disorder, a severe form of anxiety. Nature 1984; 310:683–685Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Charney DS, Heninger GR: Noradrenergic function and the mechanism of action of antianxiety treatment, II: the effect of long-term imipramine treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:473–481Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Goddard AW, Charney DS: Toward an integrated neurobiology of panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:4–11Medline, Google Scholar

21. Charney DS, Woods SW, Nagy LM, Southwick SM, Krystal JH, Heninger GR: Noradrenergic function in panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1990; 51:5–11Google Scholar

22. Weissman MM, Leckman JF, Merikangas KR, Gammon GD, Prusoff BA: Depression and anxiety disorders in parents and children: results from the Yale Family Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:845–852Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Turner SM, Beidel DC, Costello A: Psychopathology in the offspring of anxiety disorders patients. J Consult Clin Psychol 1987; 55:229–235Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Sylvester CE, Hyde TS, Reichler RJ: The Diagnostic Interview for Children and Personality Inventory for Children in studies of children at risk for anxiety disorders or depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1987; 26:668–675Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Gersten M, Hirshfeld DR, Meminger SR, Herman JB, Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N: Behavioral inhibition in children of parents with panic disorder and agoraphobia: a controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:463–470Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Manassis K, Bradley S, Goldberg S, Hood J, Swinson R: Behavioural inhibition, attachment and anxiety in children of mothers with anxiety disorders. Can J Psychiatry 1995; 40:87–92Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Battaglia M, Bajo S, Strambi L, Brambilla F, Castronovo C, Vanni G, Bellodi L: Physiological and behavioral responses to minor stressors in offspring of patients with panic disorder. J Psychiatr Res 1997; 31:365–376Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Non-Patient Edition (SCID-NP, Version 1.0). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

29. Hollingshead AB: Four-Factor Index of Social Status. New Haven, Conn, Yale University, Department of Sociology, 1975Google Scholar

30. Harman HH: Modern Factor Analysis, 3rd ed. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1976Google Scholar

31. Boyd JH, Burke JD, Gruenberg E, Holzer CE, Rae DS, George LK, Karno M, Stoltzman R, McEvoy L, Nestadt G: Exclusion criteria of DSM-III: a study of co-occurrence of hierarchy-free syndromes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:983–989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Kessler RC, Stang PE, Wittchen HV, Ustun TB, Roy-Byrne PP, Walters EE: Lifetime panic-depression comorbidity in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:801–808Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Applied Logistic Regression. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1989Google Scholar

34. Weinberg CR: Toward a clearer definition of confounding. Am J Epidemiol 1993; 137:1–8Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Liang KY, Zeger SL: Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 1986; 73:13–22Crossref, Google Scholar

36. Diggle PJ, Liang K-Y, Zeger S: Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 1994Google Scholar

37. Stata Reference Manual, Release 5. College Station, Tex, Stata Corp, 1997Google Scholar

38. Maser JD, Cloninger CR: Comorbidity of Anxiety and Mood Disorders. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

39. Kendler KS, Heath AC, Martin NG, Eaves LJ: Symptoms of anxiety and symptoms of depression: same genes, different environments? Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:451–457Google Scholar

40. Kendler KS, Heath A, Martin NG, Eaves LJ: Symptoms of anxiety and depression in a volunteer twin population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:213–221Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Johnson MR, Lydiard RB: Comorbidity of major depression and panic disorder. J Clin Psychol 1998; 54:201–210Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Matheny AP: Children’s behavioral inhibition over age and across situations: genetic similarity for a trait during change. J Pers 1989; 57:215–235Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Robinson JL, Kagan J, Reznick JS, Corley R: The heritability of inhibited and uninhibited behavior: a twin study. Dev Psychol 1992; 28:1030–1037Google Scholar

44. DiLalla LF, Kagan J, Reznick JS: Genetic etiology of behavioral inhibition among 2-year-old children. Infant Behav Dev 1994; 17:405–412Crossref, Google Scholar

45. Biederman J, Rosenbaum JF, Hirshfeld DR, Faraone SV, Bolduc EA, Gersten M, Meminger SR, Kagan J, Snidman N, Reznick JS: Psychiatric correlates of behavioral inhibition in young children of parents with and without psychiatric disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:21–26Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Biederman J, Rosenbaum JF, Bolduc-Murphy EA, Faraone SV, Chaloff J, Hirshfeld DR, Kagan J: A 3-year follow-up of children with and without behavioral inhibition. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1993; 32:814–821Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar