What Is a “Mood Stabilizer”? An Evidence-Based Response

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The term “mood stabilizer” is widely used in the context of treating bipolar disorder, but the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not officially recognize the term, and no consensus definition is accepted among investigators. The authors propose a “two-by-two” definition by which an agent is considered a mood stabilizer if it has efficacy in treating acute manic and depressive symptoms and in prophylaxis of manic and depressive symptoms in bipolar disorder. They review the literature on the efficacy of agents in any of these four roles to determine which if any agents meet this definition of mood stabilizer. METHOD: The authors conducted a comprehensive review of English-language literature describing peer-reviewed, U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality class A controlled trials in order to identify agents with efficacy in any of the four roles included in their definition of a mood stabilizer. The trials were classified as positive or negative on the basis of primary outcome variables. An “FDA-like” criterion of at least two positive placebo-controlled trials was required to consider an agent efficacious. The authors also conducted a sensitivity analysis by raising and relaxing the criteria for including trials in the review. RESULTS: The authors identified 551 candidate articles, yielding 111 class A trials, including 81 monotherapy trials with 95 independent analyses published through June 2002. Lithium, valproate, and olanzapine had unequivocal evidence for efficacy in acute manic episodes, lithium in acute depressive episodes and in prophylaxis of mania and depression, and lamotrigine in prophylaxis (relapse polarity unspecified). Thus, only lithium fulfilled the a priori definition of a mood stabilizer. Relaxing the quality criterion did not change this finding, while raising the threshold resulted in no agents fulfilling the definition. CONCLUSIONS: When all four treatment roles are considered, the evidence supported a role for lithium as first-line agent for treatment of bipolar disorder. The analysis also highlights unmet needs and promising agents and provides a yardstick for evaluating new treatment strategies.

The term “mood stabilizer” is in wide use in the context of treating bipolar disorder. However, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not officially recognize the term, and investigators have no consensus definition. Some have suggested that an agent is a mood stabilizer if it has efficacy in decreasing the frequency or severity of any type of episode in bipolar disorder and if it does not worsen the frequency or severity of other types of episodes (1–3). Others have proposed a more stringent definition that requires that an agent possess efficacy in treating both manic and depressive symptoms (4). To our knowledge, no reviews have systematically assessed evidence from clinical trials in light of either of these definitions.

Based on the treatment needs of persons with bipolar disorder, we propose—similar to the more stringent definition—that an agent be considered a mood stabilizer if it has efficacy in each of four distinct uses: 1) treatment of acute manic symptoms, 2) treatment of acute depressive symptoms, 3) prevention of manic symptoms, and 4) prevention of depressive symptoms.

Doesn’t this “two-by-two” definition set the bar too high? Can we expect any single agent to treat all phases of bipolar disorder? It is clear that monotherapy is the exception rather than the rule (5, 6). Clinical practice has of necessity moved toward rational polypharmacy for various situations (3), and this approach has been endorsed by numerous evidence-based (e.g., references 7–10) and survey-based (11) clinical practice guidelines. Nonetheless, the two-by-two conceptualization clarifies characteristics of the ideal agent.

What about psychotic symptoms? These symptoms are not considered in the definition because they are not a core aspect of bipolar disorder, they occur in a minority of cases, and they are not required for the diagnosis, according to DSM-IV-TR.

What about mixed and hypomanic episodes? Debate continues regarding the definition of mixed episodes and the significance of dysphoria during hypomanic or manic episodes (12, 13). Most studies treat mixed or dysphoric mania as a subset of mania rather than of depressive episodes in terms of phenomenology (12, 14) and treatment response (12, 15, 16). The core symptom sets for mania and hypomania are identical, and the syndromes are distinguished only by the presence of functional impairment, the need for hospitalization, or psychosis in mania (DSM-IV-TR). Therefore, we consider mixed and hypomanic episodes within the overall category of mania and note results for these episodes separately.

Having proposed this conceptualization a priori, we reviewed all available English-language, peer-reviewed, controlled clinical trials of agents used for bipolar disorder through mid-2002 against this definition. We took an “FDA-like” approach, identifying as mood stabilizers those agents with at least two positive placebo-controlled trials in each of the four uses. We subsequently varied this threshold in a sensitivity analysis to provide relaxed and more stringent criteria and, where evidence permitted, also addressed the looser definition of mood stabilizer.

Method

Locating Trials

We sought to locate all pharmacologic treatment studies for bipolar disorder that fulfilled the following criteria: 1) published in a peer-reviewed journal through June 2002; 2) investigated an intervention in a group of patients with bipolar disorder (N=4 or more) or reported separately results for subgroups of bipolar disorder subjects from a diagnostically heterogeneous group; 3) specified quantitative outcome variables and formal statistical analyses; and 4) reported in English.

Literature databases, including MEDLINE, PsychLIT, and the Cochrane Collaboration database, were searched. Authors known to be actively working in the field in the United States and Europe were contacted regarding further work in print or in press. The bibliography of each located article was searched for additional articles. This step was repeated iteratively until no further unreviewed references were found.

Categorizing Trials

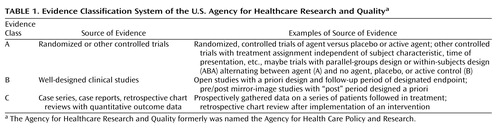

From the trials that were located we culled class A studies (controlled trials), defined according to the criteria of the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (formerly the U.S. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research) (17) as operationalized in prior studies (9, 18) and summarized in Table 1. Evidence-grading agreement between co-authors was high (kappa=0.85).

The class A trials were further categorized according to the four uses. Trials of treatments for acute manic (including hypomanic or mixed episodes) or depressive episodes included subjects who were acutely ill and examined the effects of treatment during a single episode of illness. Prophylactic trials (we use this term rather than “continuation” or “maintenance,” since differentiation between states of recovery and remission [19] was not typically made) typically included subjects with some level of subacute symptoms and examined the effects of treatment over periods of months to years.

Trials were also classified according to the use of placebo versus active control and according to whether they used parallel-groups or within-subjects (ABA) designs alternating agent (A) and no agent, placebo, or active control (B). They were also separated according to whether they examined use of monotherapy or combination therapy, with the latter group including studies of subjects who were receiving an ongoing medication regimen to which an additional agent (or control condition) was added.

The trials were also classified according to agent of interest. With placebo-controlled trials, identification of the agent of interest was straightforward. In trials in which two agents were compared to placebo, both were listed as agents of interest. With active control trials (e.g., lithium versus chlorpromazine or carbamazepine versus lithium for acute mania), a judgment of which agent was the agent of interest and which was the established comparator was made on the basis of study design features reported in the article.

Combining Trials

Traditional reviews treat study findings as qualitative data and integrate them according to the reviewer’s judgment of the studies’ relevance, quality, etc. On the other end of the spectrum, meta-analytic techniques treat study findings in aggregate as an interval datum, converting all to a common metric and making a summary judgment based on statistical techniques (20). Recent meta-analytic reviews of treatments for bipolar disorder have evaluated the efficacy of carbamazepine in prophylaxis (21), lithium in acute mania (22), lithium in prophylaxis (23), and valproate in maintenance (24).

Although meta-analytic techniques could potentially be used for establishing each individual use considered in our definition of mood stabilzers, they cannot easily be used for the synthesis across uses. Moreover, we anticipated small numbers of class A trials in some use subcategories for several agents. We therefore treated trial findings as categorical data (positive/negative). As our a priori criterion we opted for an FDA-like approach, requiring at least two placebo-controlled trials with positive findings to be considered efficacious in that use. For placebo-controlled trials, the positive-trial criterion was a better effect of the agent of interest than of placebo at p<0.05 (for parallel-groups trials) or a ≥50% relapse rate with placebo substitution (for ABA trials). For active control trials (parallel-groups or ABA trials), the positive-trial criterion was a better effect of the agent of interest than of the comparator or an effect of the agent of interest that was equal to or better than that of the comparator and better than baseline at p<0.05.

Trials were categorized as positive or negative on the basis of the primary outcome variables. If independent analyses were done for several uses or agents, the trial was categorized for each separately (e.g., two agents versus placebo) and noted as such in the results tables. Most prophylaxis trials measured efficacy in preventing relapse to either (hypo)mania or depression rather than to each type of episode separately; where these latter more specific outcomes could be identified among primary or secondary analyses, each was used as a primary outcome variable.

After having analyzed findings for agents according to our main criterion, we conducted a sensitivity analysis both by raising the threshold to use only parallel-groups, placebo-controlled class A trials and by lowering the threshold to include active control class A trials. We also reviewed available data for mixed and hypomanic episodes. Finally, we reviewed the evidence according to a broader mood stabilizer definition suggested by some authors (1–3).

Results

Data Set

Among several thousand citations, we located 551 candidate articles, which provided 111 class A trials (81 monotherapy trials, 30 combination therapy trials; the findings from the combination trials are not presented because of space limitations, but the results are available from the first author on request). Monotherapy trials provided 95 independent analyses, including 48 for treatment of acute mania, 16 for acute depression, and 31 for prophylaxis.

Several classic trials were excluded because of a lack of study group statistics (e.g., references 25 and 26) or a lack of separation of bipolar disorder subjects from subjects with other disorders (e.g., reference 27). Several earlier reports were superseded by later extensions of the same dataset (e.g., references 28 and 29). Two prophylaxis trials were included, although they focused on subsets of bipolar disorder patients, such as those with rapid cycling (30) or with comorbid borderline personality disorder (31). One trial of treatment for acute mania was excluded because it lasted for only one day (32).

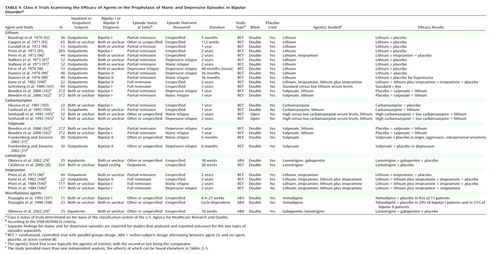

The trial characteristics and results are summarized in Table 2, Table 3, and Table 4. For treatment of acute mania, at least one positive placebo-controlled trial supported the efficacy of lithium, valproate, haloperidol, olanzapine, clonazepam, verapamil, or lecithin. In addition, evidence from at least one active control trial supported the efficacy of carbamazepine, lamotrigine, pimozide, risperidone, lorazepam, ECT, ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA) plus ascorbic acid, l-tryptophan, and d,l-propranolol.

In acute depression, at least one positive placebo-controlled trial supported the efficacy of fluoxetine, imipramine, lithium, lamotrigine, piribedil, and ascorbic acid. Evidence from at least one active control trial supported the efficacy additionally of tranylcypromine, ECT, a low-vanadium diet, and EDTA plus ascorbic acid.

At least one positive placebo-controlled trial supported the prophylactic efficacy of lithium, valproate, and lamotrigine, with one trial indicating a trend toward significant effects of carbamazepine versus placebo (103). No additional agents were supported by evidence from active control trials. However, one trial showed equivalence among low- and high-dose carbamazepine and lithium for prophylaxis of both mania and depression (105), and one trial showed equivalence between carbamazepine and lithium (104). These are not ranked as positive trials because they did not meet the a priori criteria of both including data indicating improvement over baseline and exceeding effects of comparator(s).

Candidate Mood Stabilizers According to the “Two-by-Two” Definition

Data for agents that had at least two class A trials (positive or negative), as shown in Table 2, Table 3, and Table 4, and that were therefore candidates for mood stabilizer status, are summarized in Table 5, Table 6, and Table 7. These tables are organized with the highest quality trials (placebo-controlled, parallel-groups trials) listed in the leftmost column, other placebo-controlled (ABA) trials in the next column to the right, and active control trials following rightward.

The trial quality threshold can be conceptually “moved” to the left to raise the evidence threshold or to the right to relax the requirement in a post hoc categorical sensitivity analysis. Although this categorical analysis does not formally distinguish the weight of evidence on the basis of sample size (as a meta-analysis would indirectly do), interpretation of the findings can be tempered by inspection of such considerations, as noted below. Further, no notation is made as to whether a trial was adequately powered for specific comparisons. In most trials the authors did not comment on power, although the authors who did comment sometimes noted insufficient power (e.g., in a study of lithium versus placebo for prophylaxis [100]); nevertheless, by convention such trials are listed, as are those for which no comment on power is available.

For acute mania, lithium, valproate, and olanzapine unequivocally meet the definition criteria. They continue to meet the criteria if the threshold is raised to include only parallel-groups, placebo-controlled trials. Verapamil presents an equivocal case, which can easily be detected with this data array method. Its antimanic efficacy is supported by two positive placebo-controlled trials; however, the total number of subjects in these two trials, 19, is less than the 32 treated in a higher-quality negative trial. If the criterion is relaxed to include also active control trials, carbamazepine and clonazepam are included, and the evidence for verapamil is strengthened somewhat. Note also that chlorpromazine, the comparator for lithium in early trials, is also included by virtue of its being equal to lithium and better than baseline in five trials summarized in Table 2(35, 37–39, 41), although it is inferior to lithium but still better than baseline in two trials (36, 40). Haloperidol is also included by virtue of one placebo-controlled trial (55) and one active control trial (41).

For acute depression, only lithium is supported by placebo-controlled trials; however, none of these trials had a parallel-groups design. Relaxing the criterion to allow active control trials allows tranylcypromine and ECT to be included.

For prophylaxis, lithium and lamotrigine are each supported by at least two placebo-controlled trials, with the two lamotrigine trials providing analyses without regard to relapse polarity. Lithium is supported by five trials analyzing relapse to either episode, plus two trials reporting relapse specifically to mania and two reporting relapse specifically to depression; one trial, although underpowered for lithium (100), provided negative data for each polarity, and one trial (97) also provided negative data for depression prophylaxis. Evidence for a prophylactic role for valproate is equivocal, with primary analyses negative for mania and depression in the large trial of Bowden and co-workers (102), plus another trial that included subjects with comorbid personality disorder and that reported positive results for manic-like symptoms and negative results for depressive symptoms using measures relevant to, but not specific for, manic and depressive episodes (31).

Lithium also meets the higher threshold requiring parallel-groups, placebo-controlled evidence for manic (97, 99) and depressive (97, 98) episode prophylaxis, while lamotrigine does not (29). Relaxing the criterion to admit active control trials allows inclusion of three equivocal trials for carbamazepine that showed equivalence to lithium but no evidence for improvement over baseline.

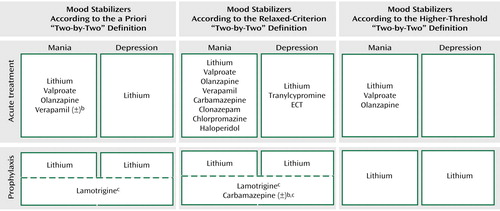

Figure 1 combines data from the foregoing tables for each of the four mood stabilizer uses according to the a priori definition and the sensitivity analyses. Only lithium fulfills the a priori definition. Relaxing the criterion to allow active control trials as evidence does not change this result. Raising the threshold to require at least two parallel-groups, placebo-controlled trials results in no single agent fulfilling the definition.

Subanalyses for Mixed Episodes and Hypomania

Four acute mania trials analyzed agent efficacy in mixed episodes or on depression ratings. Subjects with mixed episodes had similar outcomes to others in trials of olanzapine versus placebo (56, 57). In active control trials, depression ratings were not significantly different in comparisons of olanzapine versus valproate (59) and of carbamazepine versus lithium (48).

Four prophylaxis trials reported results specifically for hypomania. Lithium was more efficacious than placebo in preventing hypomanic episodes (99, 100). Nimodipine response did not differ between bipolar I disorder subjects and bipolar II disorder subjects (108). Lamotrigine demonstrated qualitatively better separation from placebo in bipolar II disorder subjects than in bipolar I disorder subjects with rapid cycling.

Looser Definition of Mood Stabilizer

The looser definition of mood stabilizer noted in the introduction—an agent with efficacy in decreasing the frequency or severity of any type of episode in bipolar disorder while not worsening the frequency or severity of other types of episodes—is actually difficult to evaluate in the clinical trials literature. While many agents have efficacy in at least one use (Figure 1), few trials measured the outcomes of both manic and depressive symptoms concurrently, and lack of evidence of a negative effect does not mean no negative effect.

Two acute mania trials showed improvement in both manic and depressive symptoms, as noted earlier (48, 59), so it is unlikely that these agents worsen either type of episode, at least in the short term. Comparing data across controlled trials, no trials reported that the agent of interest had worse performance than placebo or that the outcome of treatment was worse than baseline. One therefore must rely on noncontrolled trial data to draw conclusions about an agent’s negative effects on course. This approach is clearly needed in the case of antidepressants (109), although the degree of risk from these agents versus other factors (110) and the specific agents of risk remain controversial (111). Thus, the looser definition of mood stabilizer is surprisingly difficult to address with class A data.

Discussion

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Only class A trials were reviewed, although much information, and indeed much clinical practice, is based on class B and C studies. The only quality weighting of individual trials was separating class A trials based on control (placebo versus active) and design (parallel-groups versus ABA). Trials were combined in categorical fashion, allowing small trials to carry the same weight as multisite trials with several hundred subjects. This issue of weighting is of clear importance in meta-analytic reviews that seek to reduce effect to a single quantity (20). The reader is encouraged to investigate in particular the Cochrane Collaboration web site (www.cochrane.org), in which meta-analytic studies for a wide range of treatments are presented, with weighting not only for size but for study quality. Trials were categorized as positive or negative on the basis of only the primary outcome variables, while secondary outcome variables may also be informative (102).

There are also several variables that are clinically relevant but that could not be addressed in this analysis. For instance, some (112, 113), although not all (114) studies suggested that among these agents, lithium may have a specific antisuicide effect. Such events are seldom reported in clinical trials and, on the basis of rates reported in clinical population-based studies (e.g., references 112 and 113), would be expected to be rare. Clinical epidemiologic methods will continue to help to address this important issue. We also could not address mechanisms of action, such as the intriguing finding that according to some studies, verapamil has an antimanic effect, even though it does not cross the blood-brain barrier and likely exerts its central effects indirectly (115). Finally, since the focus of this analysis was efficacy, side effects (also often not reported in earlier trials) were not addressed. However, it is clear that issues of tolerability are of substantial importance as one moves from the realm of efficacy trials to the effectiveness of an intervention in general clinical practice (116).

It must also be added that cohort effects and publication bias may affect these results, although these effects are due to the quality of the available literature and not to the methods of this specific study. In terms of cohort effects, agents that have been in use longer—e.g., lithium—have been better studied. The absence of positive data for efficacy for some of the newer agents should not be equated with the absence of efficacy. For instance, the first unequivocally positive trial of prophylaxis with valproate was published in 2002, and this study was a small trial involving an unusual study group (subjects with both bipolar II disorder and borderline personality disorder) (31). Many studies of bipolar disorder are in the “pipeline,” and this analysis must be considered only a snapshot at this time.

Of additional interest in this regard is the relatively small number of negative studies. While the heterogeneity of the data preclude formal analysis by using funnel plots or similar methods (117), the small proportion of negative analyses published for mania (7/48, 14.6%), depression (1/16, 6.3%), and prophylaxis (8/31, 25.8%) leads the astute reader to consider whether the published literature tells the entire story—both now and for the future. Similar concerns about reporting bias against negative studies have been voiced for several years by our colleagues in medicine and public health (118).

All of these limitations were recognized at the outset. However, to address definitional issues and to cover a sample of trials this large—and to do so with uniformity—the above analytic decisions needed to be made. To compensate, we presented the data as explicitly as possible so that readers can formulate their own interpretations. Nonetheless, comparison with the conclusions of meta-analytic reviews indicates that our main interpretations are reasonable.

Key Findings and Comparison With Meta-Analyses

Among the most striking and clinically important findings are the large number of trials in acute mania and the large number of agents meeting the criteria for efficacy in acute mania. This large number of agents with efficacy for acute mania stands in marked contrast to the relative paucity of agents for acute depression. These findings underscore the “ ‘bias’ towards the importance of mania over the last 50 years” (3). Moreover, the evidence for efficacy of agents in acute depression is the least robust, since raising the threshold resulted in no agents meeting the criteria for efficacy (Figure 1).

The findings of our categorical review are in overall agreement with meta-analytic reviews that studied individual uses for agents. The findings include documentation of the efficacy for lithium in acute mania (22) and prophylaxis (23) and equivocal support for carbamazepine (21) and valproate (24) in prophylaxis.

Defining “Mood Stabilizer” and Identifying Needs of the Field

By our a priori definition, lithium alone currently fulfills the definition of mood stabilizer, and no other agents achieve that status even with the relaxed criteria (Figure 1). It is important for clinicians and researchers to recognize the strength of the evidence for lithium’s efficacy, particularly in acute mania and prophylaxis, as well as the gaps in efficacy data for other more widely prescribed agents. Taking acute and prophylactic needs together, our analysis supports a role for lithium as first-line treatment for bipolar disorder.

Nevertheless, lithium monotherapy has been the exception rather than the rule (5, 6), and its introduction has had only modest effects on various aspects of outcome for bipolar disorder (119). These studies provide prima facie evidence of the substantial need that lithium has not met, and additional strategies must be developed.

Specific needs include most prominently additional agents with efficacy for acute depression, continued exploration of prophylaxis alternatives for cases where lithium fails or is not tolerated, and greater exploration of combination therapies in high-quality controlled clinical trials. These analyses identify potential components for trials combining agents “from above” and “from below”(respectively, for manic symptoms and for depressive symptoms, per reference 3). They also suggest a second look at several forgotten agents that may yet hold promise (e.g., verapamil, ascorbic acid).

Finally, in addition to providing a standardized review of a wide array of agents used in bipolar disorder, this report suggests a conceptual framework for the field by providing an evidence-based definition for the commonly used but ill-defined term “mood stabilizer.” This conceptualization provides a yardstick by which to assess other potential agents and combinations.

From Clinical Trials to Clinical Practice

An analysis such as this presents the evidence basis from only published class A controlled trials. This literature addresses only a small proportion of the needs encountered in clinical practice, as inspection of the major evidence-based guidelines for bipolar disorder has revealed (7–10). Some suspect that the limited scope of clinical needs addressed in the literature is at least in part responsible for the poor rates of adherence to mental health clinical practice guidelines (120). Thus, the caveats that apply to the class A clinical trials literature also apply to the conclusions of this study.

We as a field are therefore left with the important questions: What is the applicability of these findings to those who are too ill or otherwise do not qualify or wish to participate in randomized, controlled trials? What of those for whom first-, or second-, and third-line treatments have failed? What of those who cannot tolerate treatment with these agents? As the field becomes more cognizant of the limitations of efficacy data in general (116, 121, 122), we must begin to consider these issues in “messier” effectiveness samples, as several large studies are currently doing (116, 123, 124).

What role, then, can these results play? This analysis may provide a kernel of organization, both conceptually and in terms of data, on which further efficacy and effectiveness studies can build. It can assist investigators in identifying lacunae in the current clinical trials literature that are not readily apparent from comparing multiple review articles with disparate assumptions and methods.

This review can also assist the clinician in evaluating claims from various quarters about this or that agent being a “mood stabilizer.” This review will have served its purpose if its readers, rather than accepting or rejecting the claims at face value, respond rather with the next logical questions: “For what specific use? How strong are the data?”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Earlier versions of this work were reported at the 155th annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Philadelphia, May 18–23, 2002. Received Jan. 22, 2003; revision received June 11, 2003; accepted June 13, 2003. From the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University; and Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Providence, R.I. Address reprint requests to Dr. Bauer, VAMC-116A, 830 Chalkstone Ave., Providence, RI 02806; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by VA Cooperative Study 430.

Figure 1. Agents Meeting A Priori, Relaxed-Criterion, and Higher-Threshold Two-by-Two Definitions of Mood Stabilizera

aThis summary figure consolidates the information from Tables 2–7 to provide a graphical illustration of the agents that meet the “two-by-two” criteria for a mood stabilizer: that the agent has support from class A efficacy studies for the treatment of acute manic symptoms, the treatment of acute depressive symptoms, the prevention of manic symptoms, and the prevention of depressive symptoms. Only lithium meets the a priori criteria as a mood stabilizer (top panel). Sensitivity analysis indicates that lowering the criteria threshold does not change these results (center panel), while raising the threshold does not identify any agents as mood stabilizers (bottom panel). See text for details.

bEquivocal results (±) for this agent. See text for details.

cEfficacy of agent is supported by prophylaxis studies that examined relapse to episode, with relapse to mania versus depression not specified. In contrast, lithium is supported by enough accumulated studies to reach the mood stabilizer criteria separately for each episode type.

1. Sachs GS: Treatment-resistant bipolar depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1996; 19:215–236Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Bowden CL: New concepts in mood stabilization: evidence for the effectiveness of valproate and lamotrigine. Neuropsychopharmacology 1998; 19:194–119Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Ketter TA, Calabrese JR: Stabilization of mood from below versus above baseline in bipolar disorder: a new nomenclature. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:146–151Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Calabrese JR, Rapport DJ: Mood stabilizers and the evolution of maintenance study designs in bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60(suppl 5):5–13Google Scholar

5. Sachs G, Lafer B, Truman C, Noeth M, Thibault A: Miracle, myth, and misunderstanding. Psychiatr Annals 1994; 24:299–306Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Unützer J, Simon G, Pabiniak C, Bond K, Katon W: The treated prevalence of bipolar disorder in a large staff-model HMO. Psychiatr Serv 1998; 49:1072–1078Link, Google Scholar

7. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder (Revision). Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159(April suppl)Google Scholar

8. Haslam D, Kennedy S, Kusumakar V, Kutcher S, Matte R, Parikh S, Sharma V, Silverstone P, Yatham L: The treatment of bipolar disorder: review of the literature, guidelines, and options. Can J Psychiatry 1997; 42:67S-99SGoogle Scholar

9. Bauer MS, Callahan A, Jampala C, Petty F, Sajatovic M, Schaefer V, Wittlin B, Powell B: Clinical practice guidelines for bipolar disorder from the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Clin Psychiatry, 1999; 60:9–21Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Suppes T, Dennehy EB, Swann AC, Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Hirschfeld RMA, Keck PE, Sachs GS, Crismon ML, Toprac MG, Shon SP for the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Bipolar Disorder: Report of the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Bipolar Disorder 2000. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:288–299Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Sachs GS, Printz DJ, Kahn DA, Carpenter D: The Expert Consensus Guideline Series: Medication Treatment of Bipolar Disorder, 2000. Minneapolis, Postgraduate Medicine, 2000Google Scholar

12. McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, Pope HG Jr, Hudson JI, Faedda GL, Swann AC: Clinical and research implications of the diagnosis of dysphoric or mixed mania or hypomania. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1633–1644Link, Google Scholar

13. Bauer MS, Gyulai L, Yeh H-S, Gonnel J, Whybrow P: Testing definitions of dysphoric mania and hypomania: prevalence, clinical characteristics, and inter-episode stability. J Affect Disord 1994; 32:201–211Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Swann AC, Secunda SK, Katz MM, Croughan J, Bowden CL, Koslow SH, Berman N, Stokes PE: Specificity of mixed affective states: clinical comparison of dysphoric mania and agitated depression. J Affect Disord 1993; 28:81–89Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Dilsaver SC, Swann AC, Shoaib AM, Bowers TC, Halle MT: Depressive mania associated with nonresponse to antimanic agents. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1548–1551Link, Google Scholar

16. Swann AC, Bowden CL, Morris D, Calabrese JR, Petty F, Small J, Dilsaver SC, Davis JM: Depression during mania: treatment response to lithium or divalproex. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:37–42Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research: Depression Panel Guideline Report. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1993Google Scholar

18. Bauer MS: An evidence-based review of psychosocial interventions for bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 2001; 35:109–134Medline, Google Scholar

19. Frank E, Prien R, Jarrett R, Keller MB, Kupfer DJ, Lavori P, Rush AJ, Weissman M: Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorders. remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:851–855Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Egger M, Davey-Smith G, Altman D (eds): Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-Analysis in Context. London, BMJ Books, 2001Google Scholar

21. Dardennes R, Even C, Bange F, Heim A: Comparison of carbamazepine and lithium in the prophylaxis of bipolar disorders. a meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166:378–381Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Poolsup N, Li Wan Po A, de Oliveira IR: Systematic overview of lithium treatment in acute mania. J Clin Pharm Ther 2000; 25:139–156Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Burgess S, Geddes J, Hawton K, Townsend E, Jamison K, Goodwin G: Lithium for maintenance treatment of mood disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001; 3:CD003013Google Scholar

24. Macritchie KA, Geddes JR, Scott J, Haslam DR, Goodwin GM: Valproic acid, valproate and divalproex in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001; 3:CD003196Google Scholar

25. Goodwin FK, Murphy DL, Bunney WE: Lithium-carbonate treatment in depression and mania. a longitudinal double-blind study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1969; 21:486–496Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Ballenger JC, Post RM: Therapeutic effects of carbamazepine in affective illness: a preliminary report. Commun Psychopharmacol 1978; 2:159–175Medline, Google Scholar

27. Fieve RR, Platman SR, Plutchik RR: The use of lithium in affective disorders, II: prophylaxis of depression in chronic recurrent affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1968; 125:492–498Link, Google Scholar

28. Frye M, Ketter TA, Kimbrell TA, Dunn RT, Speer AM, Osuch EA, Luckenbaugh DA, Cora-Locatelli G, Leverich GS, Post RM: A placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine and gabapentin monotherapy in refractory mood disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 20:607–614Google Scholar

29. Obrocea GV, Dunn RM, Frye MA, Ketter TA, Luckenbaugh DA, Leverich GS, Speer AM, Osuch EA, Jajodia K, Post RM: Clinical predictors of response to lamotrigine and gabapentin monotherapy in refractory affective disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 51:253–259Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Calabrese JR, Suppes T, Bowden CL, Sachs GS, Swann AC, McElroy SL, Kusumakar V, Ascher JA, Earl NL, Greene PL, Monaghan ET: A double-blind placebo controlled, prophylaxis study of lamotrigine in rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:841–850Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Frankenberg FR, Zanarini MC: Divalproex sodium treatment of women with borderline personality disorder and bipolar II disorder: a double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:442–444Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Meehan K, Zhang F, David S, Tohen M, Janicak P, Small J, Koch K, Rizk R, Walker D, Tran P, Breier A: A double-blind randomized comparison of the efficacy and safety of intramuscular injections of olanzapine, lorazepam, or placebo in treating acutely agitated patients diagnosed with bipolar mania. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001; 21:389–397Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Maggs R: Treatment of manic illness with lithium carbonate. Br J Psychiatry 1963; 109:56–65Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Stokes PE, Shamoian CA, Stoll PM, Patton MJ: Efficacy of lithium as acute treatment of manic depressive illness. Lancet 1971; 1:1319–1325Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Johnson G, Gershon S, Hekimian LJ: Controlled evaluation of lithium and chlorpromazine in the treatment of manic states: an interim report. Compr Psychiatry 1968; 9:563–573Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Platman SR: A comparison of lithium carbonate and chlorpromazine in mania. Am J Psychiatry 1970; 127:351–353Link, Google Scholar

37. Spring G, Schweid D, Gray C, Steinberg J, Horwitz M: A double-blind comparison of lithium and chlorpromazine in the treatment of manic states. Am J Psychiatry 1970; 126:1306–1310Link, Google Scholar

38. Johnson G, Gershon S, Burdock EI, Floyd A, Hekimian L: Comparative effects of lithium and chlorpromazine in the treatment of acute manic states. Br J Psychiatry 1971; 119:267–276Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Prien R, Caffey E, Klett C: Comparison of lithium carbonate and chlorpromazine in the treatment of mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1972; 26:146–153Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Takahashi R, Sakuma A, Itoh K, Itoh H, Kurihara M, Saito M, Watanabe M: Comparison of efficacy of lithium carbonate and chlorpromazine in mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1975; 32:1310–1318Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Shopsin B, Gershon S, Thompson H, Collins P: Psychoactive drugs in mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1975; 32:34–42Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Bowden C, Brugger A, Swann A, Calabrese J, Janicak P, Petty F, Dilsaver S, Davis J, Rush J, Small J, Trevino E, Risch C, Goodnick P, Morris D: Efficacy of divalproex vs lithium and placebo in treatment of mania. JAMA 1994; 271:918–924Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Okuma T, Inanaga K, Otsuki S, Sarai K, Takahashi R, Hazama H, Mori A, Watanabe M: Comparison of the antimanic efficacy of carbamazepine and chlorpromazine: a double-blind controlled study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1979; 66:211–217Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Lerer B, Moore N, Meyendorff E, Cho SR, Gershon S: Carbamazepine versus lithium in mania: a double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry 1987; 48:89–93Medline, Google Scholar

45. Lusznat R, Murphy D, Nunn C: Carbamazepine vs lithium in the treatment and prophylaxis of mania. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 153:198–204Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Brown D, Silverstone T, Cookson J: Carbamazepine compared to haloperidol in acute mania. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1989; 4:229–238Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Okuma T, Yamashita I, Takahashi R, Itoh H, Otsuki S, Watanabe S, Sarai K, Hazama H, Inanaga K: Comparison of the antimanic efficacy of carbamazepine and lithium carbonate by double-blind controlled study. Pharmacopsychiatry 1990; 23:143–150Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Small J, Klapper M, Milstein V, Kellams J, Miller M, Marhenke J, Small I: Carbamazepine compared with lithium in the treatment of mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:915–921Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Emrich HM, Zerssen DV, Kissling W, Moller HJ, Windorfer A: Effect of sodium valproate on mania: the GABA hypothesis of affective disorders. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr 1980; 229:1–16Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Pope H, McElroy S, Keck P, Hudson J: Valproate in the treatment of acute mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:62–68Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Freeman TW, Clothier JL, Pazzaglia P, Lesem MD, Swann AC: A double-blind comparison of valproate and lithium in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:108–111Link, Google Scholar

52. Vasudev K, Goswami U, Kohli K: Carbamazepine and valproate monotherapy: feasibility, relative safety and efficacy and therapeutic drug monitoring in manic disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000; 150:15–23Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Ichim L, Berk M, Brook S: Lamotrigine compared with lithium in mania: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2000; 12:5–10Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Cookson JC, Silverstone T, Wells B: A double-blind controlled study of pimozide vs chlorpromazine in mania. Neuropharmacology 1979; 18:1011–1013Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. Garfinkel PE, Stancer HC, Persad E: A comparison of haloperidol, lithium carbonate and their combination in the treatment of mania. J Affect Disord 1980; 2:279–288Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. Tohen M, Sanger TM, McElroy SL, Tollefson GD, Chengappa KNR, Daniel DG, Petty F, Centorrino F, Wang R, Grundy SL, Greaney MG, Jacobs TG, David SR, Toma V (Olanzapine HGEH Study Group): Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:702–709Abstract, Google Scholar

57. Tohen M, Jacobs TG, Grundy SL, McElroy SL, Banov MC, Janicak PG, Sanger T, Risser R, Zhang F, Toma V, Francis J, Tollefson GD, Breier A: Efficacy of olanzapine in acute bipolar mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:841–849Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58. Segal J, Berk M, Brook S: Risperidone compared with both lithium and haloperidol in mania: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Clin Neuropharmacol 1998; 21:176–180Medline, Google Scholar

59. Tohen M, Baker RW, Altshuler LL, Zarate CA, Suppes T, Ketter TA, Milton DR, Risser R, Gilmore JA, Breier A, Tollefson GA: Olanzapine versus divalproex in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1011–1017Link, Google Scholar

60. Edwards R, Stephenson U, Flewett T: Clonazepam in acute mania: a double blind trial. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1991; 25:238–242Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Chouinard G, Young SN, Annable L: Antimanic effect of clonazepam. Biol Psychiatry 1982; 18:451–466Google Scholar

62. Bradwejn J, Shriqui C, Koszycki D, Meterissian G: Double-blind comparison of the effects of clonazepam and lorazepam in acute mania. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1990; 10:403–408Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63. Clark HM, Berk M, Brook S: A randomized controlled single blind study of the efficacy of clonazepam and lithium in the treatment of acute mania. Hum Psychopharmacol 1997; 12:325–328Crossref, Google Scholar

64. Giannini AJ, Houser WL Jr, Loiselle RH, Giannini MC, Price WA: Antimanic effects of verapamil. Am J Psychiatry 1984; 141:1602–1603Link, Google Scholar

65. Dubovsky SL, Franks RD, Allen S, Murphy J: Calcium antagonists in mania: a double-blind study of verapamil. Psychiatry Res 1986; 18:309–320Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

66. Janicak PG, Sharma RP, Pandey G, Davis JM: Verapamil for the treatment of acute mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:972–973Link, Google Scholar

67. Garza-Trevino ES, Overall JE, Hollister LE: Verapamil versus lithium in acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:121–122Link, Google Scholar

68. Hoschl C, Kozeny J: Verapamil in affective disorders: a controlled, double-blind study. Biol Psychiatry 1989; 25:128–140Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

69. Walton SA, Berk M, Brook S: Superiority of lithium over verapamil in mania: a randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57:543–546Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

70. Naylor GJ, Smith AHW: Vanadium: a possible aetiological factor in manic depressive illness. Psychol Med 1981; 11:249–256Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

71. Cohen BM, Lipinski JF, Altesman RL: Lecithin in the treatment of mania: double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry 1982; 139:1162–1164Link, Google Scholar

72. Chouinard G, Young SN, Annable L: A controlled clinical trial of l–tryptophan in acute mania. Biol Psychiatry 1985; 20:546–557Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

73. Giannini AJ, Loiselle RH, Price WA, Giannini MC: Comparison of antimanic efficacy of clonidine and verapamil. J Clin Pharmacol 1985; 25:307–308Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

74. Giannini AJ, Pascarzi GA, Loiselle RH, Price WA, Giannini MC: Comparison of clonidine and lithium in the treatment of mania. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:1608–1609Link, Google Scholar

75. Small JG, Klapper MH, Kellams JJ, Miller MJ, Milstein V, Sharpley PH, Small IF: Electroconvulsive treatment compared with lithium in the management of manic states. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:727–732Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

76. Kay DSG, Naylor GH, Smith AHW, Greenwood C: The therapeutic effect of ascorbic acid and EDTA in bipolar psychosis: double-blind comparisons with standard treatments. Psychol Med 1984; 14:533–539Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

77. Prange AJ, Wilson IC, Lynn CL, Alltop LB, Stikeleather RA: l–Tryptophan in mania: contribution to a permissive hypothesis of affective disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1974; 30:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

78. Emrich HM, von Zerssen D, Moller HJ, Kissling W, Cording C, Schietsch HJ, Riedel E: Action of propranolol in mania: comparison of the effects of the d- and the l-stereoisomer. Pharmakopsychiatr Neuropsychopharmakol 1979; 12:295–304Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

79. Janicak PG, Sharma RP, Easton M, Comaty JE, Davis JM: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of clonidine in the treatment of acute mania. Psychopharmacol Bull 1989; 25:243–245Medline, Google Scholar

80. Cohn JB, Collins G, Ashbrook E, Wernicke JF: A comparison of fluoxetine, imipramine and placebo in patients with bipolar depressive disorder. Clin Psychopharmacol 1989; 4:313–322Crossref, Google Scholar

81. Himmelhoch JM, Thase ME, Mallinger AG, Houck P: Tranylcypromine versus imipramine in anergic bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:910–916Link, Google Scholar

82. Thase MF, Mallinger AG, McKnight D, Himmelhoch JM: Treatment of imipramine-resistant recurrent depression, IV: a double-blind crossover study of tranylcypromine for anergic bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:195–198Link, Google Scholar

83. Goodwin FK, Murphy DL, Dunner DL, Bunney WE Jr: Lithium response in unipolar versus bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 1972; 129:44–47Link, Google Scholar

84. Baron M, Gershon ES, Rudy V, Jonas WZ, Buchsbaum M: Lithium carbonate response in depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1975; 32:1107–1111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

85. Mendels J: Lithium in the treatment of depression. Am J Psychiatry 1976; 133:373–378Link, Google Scholar

86. Ballenger JC, Post RM: Carbamazepine in manic-depressive illness: a new treatment. Am J Psychiatry 1980; 137:782–790Link, Google Scholar

87. Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Sachs GS, Ascher JA, Monaghan E, Rudd GD (Lamictal 602 Study Group): A double-blind placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine monotherapy in outpatients with bipolar I depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:79–88Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

88. Sackeim HA, Decina P, Kanzler M, Kerr B, Malitz S: Effects of electrode placement on the efficacy of titrated, low-dose ECT: Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:1449–1455Google Scholar

89. Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Devanand DP, Kiersky JE, Fitzsimmons L, Moody BJ, McElhiney MC, Coleman EA, Settembrino JM: Effects of stimulus intensity and electrode placement on the efficacy and cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy. N Engl J Med 1993; 328:839–846Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

90. Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Devanand DP, Nobler MS, Lisanby SH, Peyser S, Fitzsimmons L, Moody BJ, Clark J: A prospective, randomized, double-blind comparison of bilateral and right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy at different stimulus intensities. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:425–434Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

91. Post RM, Gerner RH, Carman JS, Gillin JC, Jimerson DC, Goodwin FK, Bunney WE: Effects of a dopamine agonist piribedil in depressed patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:609–615Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

92. Baastrup PC, Poulsen JC, Schou M, Thomsen K, Amdisen A: Prophylactic lithium: double blind discontinuation in manic depressive and recurrent-depressive disorders. Lancet 1970; 2:326–330Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

93. Coppen A, Noguera R, Bailey J, Burns BH, Swani MS, Hare EH, Gardner R, Maggs R: Prophylactic lithium in affective disorders: controlled trial. Lancet 1971; 2:275–279Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

94. Cundall RL, Brooks PW, Murray LG: A controlled evaluation of lithium prophylaxis in affective disorders. Psychol Med 1972; 2:308–311Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

95. Prien R, Caffey E, Klett C: Prophylactic efficacy of lithium carbonate in manic depressive illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1973; 28:337–341Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

96. Prien R, Klett C, Caffey E: Lithium carbonate and imipramine in prevention of affective episodes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1973; 29:420–425Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

97. Stallone F, Shelley E, Mendlewicz J, Fieve RR: The use of lithium in affective disorders, III: a double-blind study of prophylaxis in bipolar illness. Am J Psychiatry 1973; 130:1006–1010Link, Google Scholar

98. Fieve RR, Kumbaraci T, Dunner DL: Lithium prophylaxis of depression in bipolar I, bipolar II, and unipolar patients. Am J Psychiatry 1976; 133:925–929Link, Google Scholar

99. Dunner DL, Stallone F, Fieve RR: Lithium carbonate and affective disorders, V: a double-blind study of prophylaxis of depression in bipolar illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:117–120Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

100. Kane JM, Quitkin F, Rifkin A, Ramos-Lorenzi J, Nayak D, Howard A: Lithium carbonate and imipramine in the prophylaxis of unipolar and bipolar II illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:1065–1069Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

101. Gelenberg A, Kane J, Keller M, Lavori P, Rosenbaum J, Cole K, Lavelle J: Comparison of standard and low serum levels of lithium for maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. N Engl J Med 1989; 321:1489–1493Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

102. Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, McElroy SL, Gyulai L, Wassef A, Petty F, Pope HG, Chou JCY, Keck PE, Rhodes LJ, Swann AC, Hirschfeld RM, Wozniak PJ: A randomized, placebo-controlled 12-month trial of divalproex and lithium in treatment of outpatients with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:481–489Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

103. Okuma T, Inanaga K, Otsuki S, Sarai K, Takahashi R, Hazama H, Mori A, Watanabe S: A preliminary double-blind study on the efficacy of carbamazepine in prophylaxis of manic depressive illness. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1981; 73:95–96Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

104. Coxhead N, Silverstone T, Cookson J: Carbamazepine versus lithium in the prophylaxis of bipolar affective disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992; 85:114–118Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

105. Simhandl C, Denk E, Thau K: The comparative efficacy of carbamazepine low and high serum level and lithium carbonate in the prophylaxis of affective disorders. J Affect Disord 1993; 28:221–231Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

106. Prien RF, Kupfer DJ, Mansky PA, Small JG, Tuason VB, Voss CB, Johnson WE: Drug therapy in the prevention of recurrences in unipolar and bipolar affective disorders: report of the NIMH collaborative study group comparing lithium carbonate, imipramine, and a lithium carbonate-imipramine combination. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:1096–1104Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

107. Pazzaglia PJ, Post RM, Ketter TA, George MS, Marangell LB: Preliminary controlled trial of nimodipine in ultra-rapid cycling affective dysregulation. Psychiatry Res 1993; 49:257–272Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

108. Pazzaglia PJ, Post RM, Ketter TA, Callahan AM, Marangeli LB, Frye MA, George MS, Kimbrell TA, Leverich GS, Cora-Locatelli G, Luckenbaugh D: Nimodipine monotherapy and carbamazepine augmentation in patients with refractory recurrent affective illness. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1998; 18:404–413Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

109. Altshuler LL, Post RM, Leverich GS, Mikalauskas K, Rosoff A, Ackerman L: Antidepressant-induced mania and cycle acceleration: a controversy revisited. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1130–1138Link, Google Scholar

110. Goldberg JF, Whiteside JE: The association between substance abuse and antidepressant-induced mania in bipolar disorder: a preliminary study. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:791–795Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

111. Joffe RT, MacQueen GM, Marriott M, Robb J, Begin H, Young LT: Induction of mania and cycle acceleration in bipolar disorder: effect of different classes of antidepressant. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002; 105:427–430Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

112. Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Hennen J: Treating the suicidal patient with bipolar disorder. Ann NY Acad Sci 2001; 932:24–43Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

113. Goodwin FK, Fireman B, Simon GE, Hunkeler EM, Lee J, Revicki D: Suicide risk in bipolar disorder during treatment with lithium and divalproex. JAMA 2003; 290:1467–1473Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

114. Yerevanian BI, Koek RJ, Mintz J: Lithium, anticonvulsants and suicidal behavior in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 2003; 73:223–228Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

115. Chikhale EG, Burton PS, Borchardt RT: The effect of verapamil on the transport of peptides across the blood-brain barrier in rats: kinetic evidence for an apically polarized efflux mechanism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1995; 273:298–303Medline, Google Scholar

116. Bauer MS, Williford WO, Dawson EE, Akiskal HS, Altshuler L, Fye C, Gelenberg A, Glick H, Kinosian B, Sajatovic M: Principles of effectiveness trials and their implementation in VA Cooperative Study #430: “Reducing the Efficacy-Effectiveness Gap in Bipolar Disorder.” J Affect Disord 2001; 67:61–78Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

117. Montori V, Guyatt G: Summarizing the evidence publication bias, in User’s Guide to the Medical Literature: A Manual for Evidence-Based Clinical Practice. Edited by Guyatt G, Drummond R. Chicago, AMA Press, 2000, pp 529–545Google Scholar

118. Dickersin K: How important is publication bias? a synthesis of available data: AIDS Educ Prev 1997; 9(1 suppl):15–21Google Scholar

119. Bauer MS, McBride L: Structured Group Psychotherapy for Bipolar Disorder: The Life Goals Program, 2nd ed. New York, Springer, 2003Google Scholar

120. Bauer MS: Quantitative adherence studies of mental health clinical practice guidelines. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2002; 10:138–153Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

121. Wells KB: Treatment research at the crossroads: the scientific interface of clinical trials and effectiveness research. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:5–10Link, Google Scholar

122. Wells KB, Miranda J, Bauer MS, Bruce M, Durham M, Escobar J, Ford D, Gonzalez J, Hoagwood K, Horowitz SM, Lawson W, Lewis L, McGuire T, Pincus H, Scheffler R, Smith WA, Unützer J: Overcoming barriers to reducing the burden of affective disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 52:655–675Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

123. Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Unützer J, Bauer MS: Design and implementation of a randomized trial evaluating systematic care for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2002; 4:226–236Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

124. Sachs GS, Thase ME, Otto MW, Bauer MS, Miklowitz D, Wisniewski SR, Lavori P, Lebowitz B, Rudorfer M, Frank E, Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Bowden C, Ketter T, Marangell L, Calabrese JR, Kupfer DJ, Rosenbaum JF (STEP-BD investigators): Rationale, design, and methods of the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP=BD): a model for collaborative research. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 53:1028–1042Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar