Verapamil for the Treatment of Acute Mania: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial

Abstract

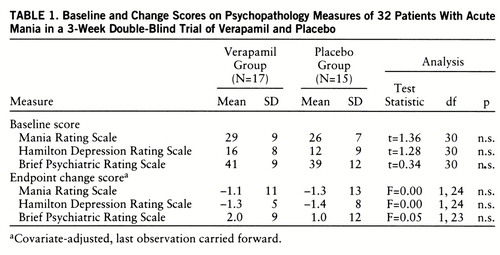

OBJECTIVE: This study investigated the efficacy of verapamil in acute mania. METHOD: The study was a 3-week double-blind, random-assignment, parallel-group, placebo-controlled inpatient trial of verapamil for patients with acute mania. Of the 32 study patients, 15 were given placebo and 17 were given verapamil. RESULTS: Mean absolute change scores on the Mania Rating Scale at endpoint, with baseline scores as the covariates, did not differ between the verapamil and placebo groups. There were no significant differences between the two groups in age, sex, and presence of psychosis. CONCLUSIONS: The investigators found no benefit of verapamil over placebo in treating acute mania. (Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:972–973)

Earlier reports noted that hypomania and acute mania improved with verapamil (1–4). Dubovsky et al. (5) subsequently reported significant improvement in five of seven patients in a random-assignment crossover comparison with placebo. The supportive literature, however, consists of anecdotal case reports, small-sample placebo crossover studies, and parallel-design comparisons with lithium or antipsychotics (6).

By contrast, Arkonac et al. (7) reported a random-assignment, double-blind crossover study of 15 manic patients (4 weeks of lithium or verapamil, 10 days of placebo, then crossover), finding that the patients improved with lithium but worsened with verapamil. The report on this study is available only in abstract form, making critical evaluation difficult. A 4-week single-blind, random-assignment trial of lithium and verapamil in 40 manic patients by Walton et al. (8) showed significantly greater improvement with lithium in comparison with verapamil on all assessments. One potential confounding factor was the use of lorazepam (5–6 mg/day) throughout the study.

To clarify verapamil's efficacy for mania, we conducted a double-blind, parallel-design, placebo-controlled trial in newly hospitalized patients.

METHOD

Patients admitted to our research unit at the University of Illinois at Chicago met the DSM-III-R criteria for an acute manic or mixed episode and had no significant medical conditions. All patients gave written informed consent and underwent a mean total medication washout period of 12.1 days (SD=10.6) (in-hospital washout mean=8.5 days, SD=5.9; prehospital mean=3.7 days, SD=9.0). Diagnosis was determined by a consensus of trained raters and the clinical team. The Mania Rating Scale (9), the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (10), and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (11) were administered at baseline and on days 3, 5, 10, 14, 17, and 21 of the trial. Intraclass correlation coefficients, based on six raters' independent ratings of five videotaped interviews, were 0.66, 0.98, and 0.91 for the three instruments, respectively.

The patients were randomly assigned to receive placebo or verapamil (80 mg) capsules three times a day, starting with two capsules on day 1, then increasing by one capsule until day 7; thereafter, they continued at the optimal dose. Vital signs were checked before each administration. Chloral hydrate (up to 4 g/day) or lorazepam (up to 2 mg/day) was used as a rescue medication during the washout period, but the dose was tapered to zero by day 10. Patients, raters, and investigators were blind to the treatment assignments.

We used an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to compute absolute change scores on the Mania Rating Scale, the Hamilton depression scale, and the BPRS at endpoint (last observation carried forward), with baseline scores as the covariates. We also analyzed data for patients who had a day 10 rating (end of rescue medications) and those who had at least a day 5 rating, to detect early changes. Chi-square and unpaired t tests (two-tailed) clarified differences in sex, age, and race.

RESULTS

Thirty-two acutely ill patients (13 female and 19 male; mean age=36.2 years, SD=10.6) entered the double-blind phase of the study. Thirty patients were in a manic episode, and one in each treatment group was in a mixed episode. The mean total and in-hospital washout days did not differ significantly between the 15 patients who received placebo and the 17 who received verapamil (t=1.5, df=30, and t=1.3, df=30, respectively). All patients given verapamil for at least 7 days tolerated the maximum dose (480 mg/day).

Ten of the 15 placebo patients and 13 of the 17 verapamil patients demonstrated psychosis at baseline, and their mean Mania Rating Scale, Hamilton depression scale, and BPRS scores did not differ. No differences were discerned at endpoint (last observation carried forward) in the comparison of covariate-adjusted mean absolute change scores (table 1). Results of ANCOVAs calculated for days 10 and 5 were also nonsignificant (for day 10, Mania Rating Scale: F=0.0, df=1,14; Hamilton depression scale: F=0.0, df=1,13; BPRS: F=0.3, df=1,13; for day 5, Mania Rating Scale: F=0.4, df=1,22; Hamilton depression scale: F=0.9, df=1,21; BPRS: F=1.0, df=1,22).

Outcomes were remarkably similar for the two groups; three placebo and four verapamil patients showed 20% improvement from their baseline Mania Rating Scale scores. At a criterion of 40% improvement, only two placebo patients and three verapamil patients responded to treatment. The two groups did not differ significantly in age (t=0.05, df=30), sex (χ2=0.00, df=1), race (χ2=0.38, df=1), presence of psychosis (χ2=0.38, df=1), total days of washout (t=1.5, df=30), total days in treatment (t=1.5, df=30), or amount of rescue medication (t=1.8, df=25).

The mean number of treatment days completed was 13.3 (SD=7.0) for the placebo group and 9.3 (SD=7.2) for the verapamil group (t=1.6, df=30, n.s.). Twenty patients continued for at least 8 days (eight in the verapamil group and 12 in the placebo group), and nine completed all 3 weeks (three in the verapamil group and six in the placebo group). Reasons for dropping out were clinical deterioration (10 verapamil subjects and eight placebo subjects) or lack of cooperation (four verapamil subjects). It is interesting that five patients taking verapamil (but none taking placebo) had to drop out during the first week.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the only prospective parallel-design, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of verapamil for acute mania. The study group size is second only to that in the study by Walton et al. (8). The treatment groups were similar in age, sex, baseline level of psychopathology, presence or absence of psychosis, amount and timing of rescue medication, total days of washout, and total treatment days. Twenty-three patients demonstrated psychosis, and mean baseline Mania Rating Scale scores were in the mid- to upper-20s, indicating moderate severity. We found no differences in efficacy between verapamil and placebo. Dropouts were a substantial issue because of the difficulties in managing bipolar patients receiving placebo or ineffective treatment.

Our negative results agree with those in two recent trials comparing verapamil and lithium (7, 8). Possible reasons for disparate findings from earlier reports include small sample sizes, differences in baseline symptom severity, inadequate doses, use of rescue medications, and short duration of treatment. Issues that have not been addressed include verapamil's efficacy for less severe mania, for maintenance/prophylaxis, and as an adjunct medication and the effectiveness of other calcium antagonists (e.g., nimodipine).

Although recent reviews suggest the possible benefit of calcium antagonists when standard treatments fail or cannot be tolerated (12, 13), three better-controlled studies (including ours) do not support verapamil's efficacy for acute mania. Thus, we believe it is premature to recommend this agent.

|

Received Aug. 27, 1997; revision received Jan. 26, 1998; accepted Feb. 26, 1998. From the Psychiatric Institute, University of Illinois at Chicago. Address reprint requests to Dr. Janicak, Psychiatric Institute, 1601 West Taylor St., Chicago, IL 60612. The authors thank Edward Altman, Psy.D., James Peterson, B.S., Sheila Dowd, M.S., and Morris Goldman, M.D., for their contributions to this work.

1 Brotman AW, Farhadi AM, Gelenberg AJ: Verapamil treatment of acute mania. J Clin Psychiatry 1986; 47:136–138Medline, Google Scholar

2 Barton BM, Gitlin MJ: Verapamil in treatment-resistant mania: an open trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1987; 7:101–103Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Dubovsky SL: Calcium antagonists in manic-depressive illness. Neuropsychobiology 1993; 27:184–192Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Dubovsky SL, Franks RD, Lifschitz M, Coen P: Effectiveness of verapamil in the treatment of a manic patient. Am J Psychiatry 1982; 139:502–504Link, Google Scholar

5 Dubovsky SL, Franks RD, Allen S, Murphy J: Calcium antagonists in mania: a double-blind study of verapamil. Psychiatry Res 1986; 18:309–320Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Janicak PG, Davis JM, Preskorn SH, Ayd FA Jr: Treatment with mood stabilizers: alternative treatment strategies, in Principles and Practice of Psychopharmacotherapy, 2nd ed. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1997, pp 441–460Google Scholar

7 Arkonac O, Kantarci E, Eradamlar N, Algur T: Verapamil vs lithium in acute manics (abstract). Biol Psychiatry 1991; 29:376SCrossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Walton SA, Berk M, Brook S: Superiority of lithium over verapamil in mania: a randomized controlled single-blind trial. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57:543–546Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA: A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:429–435Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep 1962; 10:799–812Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Dubovsky SL, Buzan RD: Novel alternatives and supplements to lithium and anticonvulsants for bipolar affective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:224–242Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Frances A, Docherty JP, Kahn DA (Steering Committee): The Expert Consensus Guidelines Series: Treatment of Bipolar Disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(Dec suppl A), p 30Google Scholar