An 8-Week Multicenter, Parallel-Group, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Sertraline in Elderly Outpatients With Major Depression

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: There have been few placebo-controlled trials of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for depressed elderly patients. This placebo-controlled study of sertraline was designed to confirm the results of non-placebo-controlled trials. METHOD: The subjects were outpatients age 60 years or older who had a DSM-IV diagnosis of major depressive disorder and a total score on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale of 18 or higher. The patients were randomly assigned to 8 weeks of double-blind treatment with placebo or a flexible daily dose of 50 or 100 mg of sertraline. The primary outcome variables were the Hamilton scale and Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scales for severity and improvement. RESULTS: A total of 371 patients assigned to sertraline and 376 assigned to placebo took at least one dose. At endpoint, the patients receiving sertraline evidenced significantly greater improvements than those receiving placebo on the Hamilton depression scale and CGI severity and improvement scales. The mean changes from baseline to endpoint in Hamilton score were –7.4 points (SD=6.3) for sertraline and –6.6 points (SD=6.4) for placebo. The rate of CGI-defined response at endpoint was significantly higher for sertraline (45%) than for placebo (35%), and the time to sustained response was significantly shorter for sertraline (median, 57 versus 61 days). There were few discontinuations due to treatment-related adverse events, 8% for sertraline and 2% for placebo. CONCLUSIONS: Sertraline was effective and well tolerated by older adults with major depression, although the drug-placebo difference was not large in this 8-week trial.

Considerable progress has been made in understanding the diagnosis and treatment of late-life depression, as summarized in the first National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference held in 1991 (1) and the update conference convened by the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry in 1996 (2). Late-life depression affects a substantial proportion of people over age 65. Overall, approximately 15% of community-dwelling elderly have clinically significant depressive symptoms, 2% to 4% suffer from a current major depressive disorder, and about 10% have minor depression (3–7).

Clinically significant depression is untreated in at least 60% of the cases (4), often has a chronic or recurrent clinical course, and is associated with greater utilization of medical services, greater morbidity and mortality from medical illnesses, lower levels of well-being, poorer physical, social, and cognitive functioning, and a greater risk of suicide, particularly in elderly men (1, 2, 8–11).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are most frequently used for treating late-life depression. SSRIs have advantages over tricyclic antidepressants in treating elderly patients because of equivalent efficacy and overall better-tolerated side effects. In particular, they are associated with substantially less orthostatic, cognitive, anticholinergic, and cardiovascular adverse effects (12–17).

Although there have been many clinical trials of the SSRIs as treatments for late-life depression, few large placebo-controlled trials have been reported. The trials using active comparators provide evidence that the several SSRIs have equivalent efficacy for older patients, equivalent both in terms of each other and in terms of the tricyclic antidepressants (14–21), and SSRI-treated patients generally experience fewer adverse effects than those taking tricyclics. One finding that emerges from published comparator trials is that the magnitude of response, compared to baseline, continues to increase when elderly patients receive a somewhat longer course of treatment for acute episodes, in the range of 8 to 12 weeks (14, 19).

Sertraline has shown equivalent effectiveness in the treatment of late-life depression according to the results of three double-blind, randomized trials including active comparators; two had 12-week durations and compared sertraline with nortriptyline (14) and fluoxetine (19), and one lasted 8 weeks and compared sertraline with amitriptyline (20).

The goal of the current trial was to evaluate the efficacy, by comparison to placebo, of sertraline for treating late-life depression. This double-blind, placebo-controlled trial allowed depressed patients with concomitant medical illnesses and included a stratified randomization based on whether patients met more stringent a priori criteria for severity and duration that were intended to identify a more endogenously depressed subgroup, which was hypothesized to yield a greater drug-placebo difference.

Method

Study Design

This was a multicenter, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sertraline in elderly community-living outpatients with DSM-IV major depressive disorder. After a single-blind placebo washout period of 4 to 14 days, subjects meeting the entry criteria were randomly assigned to 8 weeks of double-blind treatment with either sertraline or placebo. To explore the possibility of differential response, before randomization each subject was classified as to whether an “endogenous subtype” was evident. This classification was made centrally by a board-certified psychiatrist who was given all baseline clinical information and then categorized each subject as either having the endogenous subtype or not on the basis of the following criteria: 1) a score of 21 or higher on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (22), 2) an episode lasting 2 months or more, 3) two or more previous episodes of major depression, and 4) at least one of the following: melancholia (DSM-IV checklist), history of major depressive disorder in a first-degree relative, lack of a psychosocial stressor that precipitated the current episode. This endogenous versus nonendogenous distinction was then used as a stratifying factor in the randomization, but the investigators were kept blind to the factors used for stratification.

Each subject received either a 50-mg sertraline tablet or an identically appearing placebo tablet daily for the first 4 weeks, after which the dose could be increased to 100 mg/day of sertraline (or matched placebo) for the final 4 weeks on the basis of the investigator’s assessment of clinical response and tolerability. The maximum dose of sertraline was limited to 100 mg/day because results from previous comparator trials (14, 19) showed adequate response rates with doses typically in the range of 50 to 100 mg/day. In addition, not allowing titration above 50 mg for 4 weeks was designed to allow for optimal response at a lower dose before titration.

The institutional review board of each site reviewed the trial. The risks and benefits of study participation were explained to each subject, and after all questions and concerns were addressed, written informed consent was obtained before any protocol activities were undertaken.

Patient Selection

The study participants were male or female community-dwelling outpatients age 60 years or over who were recruited by 66 clinical sites between July 1997 and December 1998. The clinical sites included both psychiatric and primary care settings. To be eligible, patients had to have a current diagnosis of major depressive disorder, single episode or recurrent, without psychotic features (DSM-IV) of at least 4 weeks’ duration, with a total score of 18 or higher on the 17-item Hamilton depression scale at baseline (and with a score of 2 or higher on item 1, “depressed mood”). The diagnoses of major depressive disorder were made by using DSM-IV checklists administered by trained evaluators at screening, and they were confirmed by clinical interviews by the site investigators at the end of the placebo washout period just before randomization. In addition, only patients displaying normal or clinically insignificant abnormal results on baseline laboratory screening tests were eligible.

The exclusion criteria included a current DSM-IV diagnosis of depressive disorder with psychotic features, dementia, organic mental disorder, or mental retardation; a score less than 24 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (23); a current or past history of any psychotic disorder or bipolar disorder; a diagnosis of drug or alcohol abuse or dependence within the previous 6 months (except nicotine); a history of seizure disorder; previous nonresponse, known hypersensitivity, or contraindication to sertraline; participation in an investigational drug trial within 3 months before this trial; significant suicide risk, a need for electroconvulsive therapy, additional psychotropic drugs, or hospitalization; regular, daily use of benzodiazepines within 3 weeks, use of antidepressants within 2 weeks, use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors or fluoxetine within 5 weeks of randomization; use of a depot antipsychotic drug within 6 months of entering the study; initiation of individual or group psychotherapy within 3 months of study entry; and any clinically significant unstable medical disorder that might affect study participation (however, patients with stable medical conditions such as insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus were allowed to participate). Concomitant treatment with any other centrally active medication was prohibited except for as-needed use of zolpidem, up to 10 mg/day, or temazepam, up to 30 mg/day, for sleep during the first 4 weeks of the study, although such use was discouraged. Use of benzodiazepines as needed for anxiety was not permitted. The subjects were asked to restrict alcohol intake during the study, and they were asked about alcohol use at each visit. Subjects could be removed from the study at any time because of adverse experiences, insufficient treatment response, or worsening of depression based on the clinical judgment of the investigator.

Efficacy and Safety Evaluations

Efficacy was evaluated by using a range of outcome measures including 1) the total score on the 17-item Hamilton depression scale and scores on three subscales (anxiety/somatization, retardation, and Bech melancholia), 2) the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) severity and improvement scales (24), 3) the Patient Global Impression (a subject-rated global assessment of improvement) (24), 4) the MMSE, 5) the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (25), used to measure the subject’s perceived quality of life in various domains of functional activity, and 6) the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (26). The 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey is a subject-rated instrument designed to assess functional status and well-being; it contains scales measuring limitations in physical and social activities due to physical or emotional problems and scales measuring role limitations, bodily pain, general mental health, vitality, and general health perceptions.

Raters for the Hamilton depression scale were trained at an investigator meeting before the start of the trial. At this meeting, raters rated two videotaped Hamilton scale interviews, and the results were discussed. This procedure was repeated again at a midstudy meeting. Raters were provided were a rating algorithm to assist them in Hamilton scale ratings, and the compliance with use of this algorithm was evaluated at study monitoring visits.

The three a priori primary outcome variables were the 1) Hamilton depression scale score, 2) CGI severity rating, and 3) CGI improvement score. These measures were assessed at baseline (for Hamilton scale and CGI severity rating); at weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8; and at endpoint. Two separate measures of responder status were defined: 1) an endpoint CGI improvement score of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved) and 2) a reduction of 50% or more in Hamilton depression score from baseline. Other secondary efficacy measures were assessed at baseline and endpoint, with the last observation carried forward for subjects who did not complete the trial.

Safety evaluations were performed at study entry and at the last study visit, and they included a physical examination, laboratory assessments (including a complete blood cell count, blood chemistry screen, thyroid function tests, and urinalysis), and 12-lead ECG. Weight, vital signs, and adverse events were assessed at every study visit. All observed or volunteered adverse events, regardless of treatment group or suspected causal relationship to study drug, were recorded and rated as to severity.

Treatment compliance was monitored with pill counts at the study visits. If a count of the tablets in the returned medication indicated that the subject had not received all of the prescribed study drug, the subject was counseled about the importance of compliance and how to take study medication. If the drug compliance calculations indicated that the subject had taken less than 75% of the study medication on any two consecutive visits, the subject was removed from the study.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the two treatment groups were compared by using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for categorical variables, with clinical site as the stratification variable. Because a few sites recruited a small number of patients, the eight sites with fewer than five subjects each were pooled into one site containing 20 subjects.

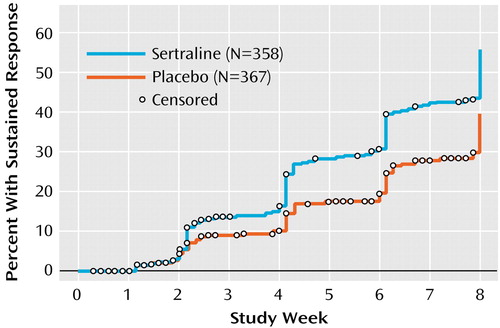

The comparison of clinical response rates was conducted by using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test (with site as a stratification variable). Time until clinical response was examined by using Kaplan-Meier survival plots, and the log-rank test was used to compare the estimated survival functions for sertraline and placebo. Sustained response was defined as the time at which a subject achieved a CGI improvement score of 1 or 2 that was maintained at least at that level in each subsequent study visit through the end of the trial.

Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to test treatment effects on the change from baseline to endpoint in the Hamilton depression score and CGI severity rating, with the baseline values used as covariates and with terms for treatment, endogenous status (endogenous versus not endogenous), site, and treatment-by-endogenous interaction included in the model. For the CGI improvement rating, a similar ANOVA model was specified without a baseline covariate. If the treatment-by-endogenous interaction was significant (p<0.10), then the interaction term was included in the primary model and simple contrasts were used to examine the treatment differences for the endogenous subgroup.

The primary analysis of the response rates based on the Hamilton depression scale and of the scores on the Hamilton depression scale and CGI severity and improvement measures were performed for two groups of subjects: 1) a modified intent-to-treat group consisting of all randomly assigned subjects who received at least one dose of study medication and had at least one valid postbaseline rating with the Hamilton depression scale or CGI during double-blind treatment and 2) the group of completers, i.e., patients who completed 8 weeks of treatment. In addition, analyses of the scores at endpoint and week 8 (for completers) were conducted for a smaller group that excluded 47 patients from two sites whose treatment was found, upon audit, to have violated guidelines for good clinical practice.

Endpoint scores (last observation carried forward) were used for the intent-to-treat analyses, and week 8 scores were used in the analyses for patients who completed treatment. Additional ANCOVA analyses were conducted on the scores at weeks 2, 4, and 6 to examine the time course of response.

The data on the secondary efficacy measures (scores on Hamilton scale subscales, Patient Global Impression, Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire, MMSE, and 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey subscales) were analyzed by using ANCOVA as already described, with baseline scores as covariates (except for the Patient Global Impression, which does not have a baseline assessment) and endpoint scores as the dependent variables. Results of these analyses are presented for the intent-to-treat group only.

Adverse events that had a 5% occurrence or more in either treatment group were tested by using chi-square methods or Fisher’s exact tests for all randomly assigned subjects who received at least one dose of study medication.

The overall number of subjects was based on an analysis using data from a previous trial of fluoxetine in the elderly (27). It was estimated that 336 patients per treatment group would need to be enrolled in order to have 80% power to detect a difference in Hamilton depression scale change scores of 2.0, with equal standard deviations of 8.0, a two-sided alpha significance level of 0.05, and a 25% discontinuation rate. Therefore, an enrollment target of 700 was set.

A two-sided alpha of 0.048 was taken as the critical level for treatment differences in efficacy, in order to account for a planned interim analysis (for which the alpha was set at 0.0052).

Results

Subject Disposition

Of the 752 subjects randomly assigned to treatment, 747 received at least one dose of study medication (371 sertraline, 376 placebo). Of these, 87 in the sertraline group and 65 in the placebo group discontinued prematurely, and 284 (77%) and 311 (83%) completed the study in the respective treatment groups. The reasons for withdrawal for sertraline and placebo included adverse events judged by the investigator to be related to the study drug (8% versus 2%, respectively), adverse events not related to the study drug (6% versus 2%), insufficient clinical response (1% versus 3%), withdrawal of consent (5% versus 6%), and miscellaneous other reasons (4% versus 3%).

Until and including week 4 all but one subject assigned to sertraline received 50 mg/day, or one tablet, and all but 10 assigned to placebo received one tablet per day. At the end of weeks 6 and 8, 61% and 63% of the sertraline-treated subjects were receiving 100 mg/day (two tablets), and 71% and 73% of the placebo-treated subjects were receiving two tablets, respectively.

Baseline Characteristics

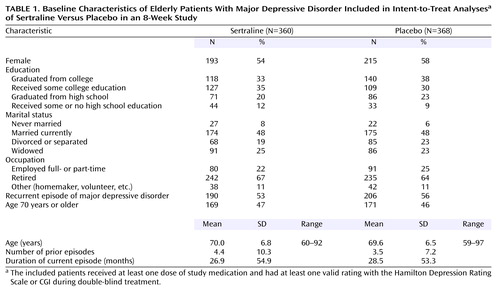

The mean age of the intent-to-treat study group was 69.8 years (range=59–97), 93% of the subjects were Caucasian, and there were slightly more women than men (Table 1). Overall, there were no significant differences between the treatment groups in any demographic or clinical characteristic at baseline.

The median duration of the depressive episode was 52 weeks in both groups. The overall mean age at illness onset was 54.3 years (SD=18.6). Overall, 54% of the subjects had recurrent major depression, and 46% were suffering from a single episode. For the subjects with recurrent depression, the mean duration since first diagnosis was 25 years (SD=17.4). The most common concomitant psychiatric disorders included a past or current history of alcohol dependence (reported by 2% overall), dysthymia (3%), generalized anxiety (1%), and panic disorder (1%). The sertraline-treated subjects were slightly more likely to be smokers (65% versus 59% of placebo subjects).

Concurrent medical conditions were reported by 93% and 94% of the sertraline- and placebo-treated subjects, respectively. For the patients with concurrent medical condition, the average number of medical problems per patient was 4.3 (SD=2.7) for sertraline and 4.4 (SD=2.9) for placebo. The most common comorbid medical conditions were unspecified arthropathies (reported by 31%), essential hypertension (34%), elevated levels of triglycerides or other lipids (22%), osteoarthrosis (15%), acquired hypothyroidism (11%), hyperplasia of prostate (19% of men), and stomach disorders (7%).

At study entry, 88% of the sertraline-treated subjects and 87% of the placebo-treated subjects were taking concomitant medications. The most common medication classes reported were the same for both treatment groups: drugs used as anti-inflammatories or in rheumatic disease and gout (40%), antihypertensive drugs (27%), hormone replacement therapy (41% of women), drugs used in the treatment of hyperlipidemia (14%), thyroid and antithyroid drugs (12%), ulcer-healing drugs (11%), β-adrenergic antagonists (11%), drugs used in diabetes (7%), hypnotics and sedatives (6%), bronchodilators (5%), and corticosteroids (4%). Overall, during the course of the trial, 87% took concomitant medication. For the subgroup of patients taking any concomitant medications, the average number of medications per patient was 5.1 (SD=3.8) for sertraline and 5.5 (SD=3.9) for placebo.

Primary Analyses

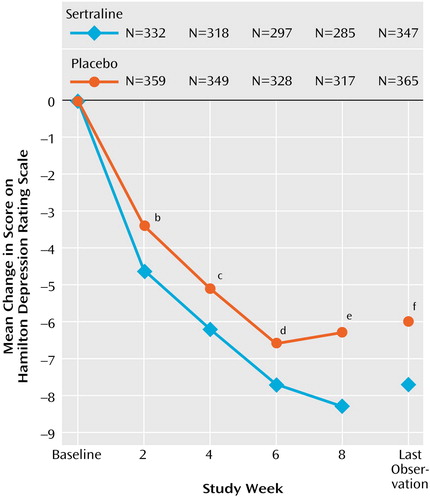

At endpoint, sertraline was significantly more effective than placebo across all three primary outcomes in the intent-to-treat group (Table 2). For the completers, sertraline was more effective on the Hamilton depression scale, CGI improvement rating, and CGI severity rating. Patients treated with sertraline achieved a mean reduction of 7.4 in their Hamilton depression scale total score by endpoint, which was statistically significantly greater than the improvement with placebo of 6.6 (Table 2); the mean decreases adjusted for baseline scores were 7.5 and 6.0 for sertraline and placebo, respectively. Statistically significant differences between sertraline and placebo were apparent as early as week 2 (Figure 1).

A significantly greater proportion of sertraline-treated patients than those treated with placebo achieved responder status according to the CGI improvement rating (i.e., CGI improvement rating of ≤2). The responder rates for sertraline versus placebo were 45% versus 35% for the intent-to-treat group (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel χ2=7.8, df=1, p=0.005) and 53% versus 37% for the completer group (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel χ2=13.8, df=1, p<0.001). The efficacy advantage in favor of sertraline was also found when the time to sustained response, based on CGI improvement rating, was assessed with a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (Figure 2). The time to sustained response was significantly less for sertraline (median=57 days) than for placebo (median=61 days) (log-rank statistic=16.1, df=1, p=0.0001).

Response was alternatively defined as a decrease in the Hamilton depression score at endpoint of 50% or greater. With this definition, the rates of response were 35% for sertraline and 26% for placebo in the intent-to-treat group (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel χ2=7.3, df=1, p=0.007). In the completer analyses, the rates were 41% and 27% (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel χ2=11.3, df=1, p=0.001).

The interaction between treatment and endogenous status for the endpoint Hamilton depression score was nearly significant in the intent-to-treat group (F=3.61, df=1, 650, p=0.06). Simple contrasts revealed that the adjusted mean Hamilton depression total score improved significantly more for the sertraline patients than for the placebo patients among the endogenous subgroup (adjusted mean change scores of –7.6 and –4.9, respectively) (F=6.12, df=1, 650, p=0.01). For the nonendogenous subgroup, the adjusted mean changes were –7.4 for sertraline and –6.9 for placebo (F=0.87, df=1, 519, p=0.35). The treatment-by-endogenous interaction was not significant for the CGI severity rating or CGI improvement score.

In the subject group with the two sites deleted, the pattern of significant findings for the overall comparison of sertraline with placebo was identical to the results for the whole group. However, the treatment-by-endogenous interaction for the endpoint Hamilton depression score was not significant when this reduced study group was examined.

Secondary Analyses

Several secondary outcomes also demonstrated statistically significant advantages of sertraline over placebo in both the intent-to-treat and completer groups. Of interest are the significant effects of sertraline on two common characteristics of late-life depression: endogenous symptoms, as measured by the Bech melancholia subscale of the Hamilton depression scale (in the intent-to-treat group with the last observation carried forward and in the completer group), and anxiety, as measured by the Hamilton depression scale anxiety/somatization factor (for the completer group) (Table 2). Although the score for patient self-rated global improvement (Patient Global Impression) at endpoint was significantly lower in the patients treated with sertraline, there was not significantly greater improvement in functional impairment measures (36-Item Short-Form Health Survey subscales). The difference between treatment groups in change from baseline to endpoint in the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire total score was not significant, but overall quality of life improved for both groups over the course of the trial.

In the efficacy analyses excluding two sites, the pattern of significant findings was identical to the results found for the full study group.

Safety

Relative to placebo treatment, the patients treated with sertraline experienced significantly (p≤0.05, Fisher’s exact test) more of the following adverse events: diarrhea, headache, nausea, somnolence, insomnia, tremor, and fatigue (Table 3). There were 28 serious adverse events in the study: 17 among the patients in the sertraline group and 11 in the placebo group. No serious adverse events in either treatment group were considered by the investigators to be related to study medication.

A total of 71 subjects were prematurely removed from the study because of treatment-emergent adverse events: 53 sertraline-treated subjects (14%) and 18 placebo-treated subjects (5%). The adverse events that contributed to discontinuation most often for the sertraline-treated subjects were nausea (3% versus <1%), diarrhea (2% versus <1%), somnolence (2% versus <1%), abdominal pain (2% versus <1%), dizziness (1% versus <1%), insomnia (each <1%), anxiety (1% versus 0%), fatigue (1% versus 0%), and tremor (1% versus <1%). The rates of discontinuation due to treatment-related adverse events were 8% for sertraline and 2% for placebo.

Four patients left the study because of serious adverse events; all were receiving sertraline. These events included depression and fecal impaction in one patient and syncope, diverticulitis, and accidental bone fracture in one patient each. One subject who received sertraline left the study because of a laboratory abnormality (abnormal liver function). There were no remarkable mean changes from baseline to endpoint in vital signs, laboratory results, or ECG findings. The only clinically significant laboratory abnormalities that affected more than 5% of either treatment group were elevated blood glucose levels (noted in 10% of both groups; the broad inclusion criteria allowed insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus) and decreased albumin levels (in 8% and 6% of the sertraline and placebo subjects, respectively). The only vital sign abnormality that affected more than 1% of either treatment group was elevated sitting systolic blood pressure, which occurred in 2% of each treatment group. A weight decrease of ≥7% occurred in 0.3% of the sertraline-treated group and 0.8% of the placebo-treated group.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the current study is the largest double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of an antidepressant ever conducted for treatment of major depressive disorder in elderly patients. Sertraline demonstrated consistent efficacy across the three primary outcome measures: total score on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, CGI improvement rating, and CGI severity rating. The size of the effect based on the Hamilton scale total score, however, was not large. At endpoint there was a 1.5-point adjusted mean difference between sertraline and placebo in the Hamilton depression score and a modest statistical effect size of 0.25 standard deviation units, somewhat larger than effects found in other major depression trials with elderly outpatients (27).

The effect sizes for categorical responses in the Hamilton depression score and the CGI improvement measure at week 8 were substantially larger. The absolute risk differences were about 10%. The response rate with sertraline of 53% for the completers is similar to response rates ranging from 48% to 58% at the same 8-week time point in previous sertraline trials of depression in late-life that used similar definitions (14, 19, 20). Two of these trials lasted 12 weeks (14, 19), and the additional 4 weeks of treatment was associated with a 15% to 20% higher responder rate. It may be that treatment of late-life depression, especially in patients with substantial medical comorbidity, has a longer response latency than is observed in younger adults. Reasons for this are uncertain, but may be attributable, in part, to the cumulative interplay of comorbidity, life stressors, and a low level of social support—variables that have been identified as being correlated with significantly slower response in the elderly (28, 29)—in addition to age-related changes in most major neurotransmitter systems (30). In the current trial, improvement in the placebo group leveled off after week 6, while the sertraline group continued to evidence improvement up to week 8, suggesting that more improvement in the sertraline group, and a greater drug-placebo difference, may have occurred if the trial had been longer.

Overall scores on the secondary measures, including the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire and the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey, did not show significant differences between sertraline and placebo at endpoint in the current study. Perhaps the 8 weeks were not long enough for the improvement in depression symptoms to translate into improved quality of life or functioning. There are insufficient data from other studies of treatment for depression in the elderly, however, to support or refute this hypothesis.

We defined, a priori, a subgroup with more endogenous depression (i.e., patients meeting specified criteria for severity, duration, and family history), with the hypothesis that the pattern of response would differ in this subgroup, as has been reported previously (29). The fact that this subgroup was smaller than predicted, 137 or 18% of the total group, limited the ability to detect differences. In addition, the validity of the criteria used to define the endogenous subgroup is uncertain. Nonetheless, there was evidence for the superiority of sertraline over placebo in this subgroup. The difference between sertraline and placebo within the endogenous subgroup (adjusted mean changes in Hamilton depression score from baseline to endpoint of –7.6 and –4.9, respectively) was larger than the difference found for the whole study group (adjusted mean changes from baseline to endpoint of –7.5 and –6.0, respectively). In addition, in the intent-to-treat group, sertraline had significantly greater efficacy in improving core melancholic symptoms as indexed by the Bech melancholia factor of the Hamilton depression scale.

Individuals suffering from late-life depression are at greater risk for anxiety disorders and anxious symptoms associated with their depression (31–33). Anxiety symptoms in the elderly may be especially likely to consist of somatic complaints, often related to medical comorbidity, which in turn increase the likelihood of noncompliance with treatment (34, 35), as well as slow the response to treatment (29). For the patients in this study who completed treatment, the effect of sertraline on the Hamilton scale anxiety/somatization factor was significantly greater than that seen with placebo, and despite a 50-mg starting dose of sertraline, the rates of early treatment-emergent anxiety or agitation were low, suggesting that sertraline may be used for elderly patients with anxious depression and that sertraline-related anxiety may not be an issue in this age group.

Only 14% of the sertraline-treated patients discontinued treatment because of treatment-emergent adverse events. There were no serious treatment-related adverse events and few laboratory or ECG abnormalities. There was no difference between sertraline and placebo in the incidence of treatment-emergent laboratory or ECG abnormalities. The 10% rate of elevated blood glucose levels was due to the attempt to allow more “real world” subjects with medical comorbidity into this trial. In addition, comparison of the rates of adverse events in the patients treated with 100 mg/day of sertraline and those receiving 50 mg/day revealed no significant differences—in the rate of either adverse events or discontinuations due to adverse events, although it should be noted that a subject generally had to tolerate 50 mg in order to receive 100 mg.

In summary, this trial provides evidence that sertraline is effective in the treatment of major depression in elderly outpatients and that the effect is greater in patients with more severe symptoms, and these results extend findings from previous trials with active comparators (14, 19, 20). Further investigations are needed to determine whether longer treatment can further improve clinical outcomes and affect non-symptom-based outcomes, such as quality of life, function, and disability, and whether maintenance treatment can prevent recurrence and relapse.

|

|

|

Received Oct. 29, 2001; revisions received March 22 and Dec. 27, 2002; accepted Jan. 10, 2003. From the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, and the Leonard Davis School of Gerontology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles; the Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco; Pfizer, Inc., New York; the Clinical Neuroscience Research Unit, Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont College of Medicine, Burlington; the Department of Psychiatry, Duke University, Durham, N.C.; California Clinical Trials, Beverly Hills, Calif.; and the Department of Psychiatry and the Behavioral Sciences, George Washington University, Washington, D.C. Address reprint requests to Dr. Schneider, KAM-400, 1975 Zonal Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90033; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by Pfizer, Inc. The authors thank Michael Murphy, M.D., Ph.D., Todd Frankum, M.S., and Penny Cohen, M.S., for assisting in the conduct of this study.

Figure 1. Weekly Change in Depression Score Among Elderly Patients With Major Depressive Disorder Included in Intent-to-Treat Analysesa of Sertraline Versus Placebo in an 8-Week Study

aThe included patients received at least one dose of study medication and had at least one valid rating with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale during double-blind treatment.

bSignificant difference between groups (F=6.7, df=1, 629, p=0.01).

cSignificant difference between groups (F=4.0, df=1, 605, p=0.045).

dSignificant difference between groups (F=3.8, df=1, 563, p=0.053).

eSignificant difference between groups (F=9.2, df=1, 540, p=0.003).

fSignificant difference between groups (F=6.6, df=1, 650, p=0.01).

Figure 2. Time to Sustained Responsea for Elderly Patients With Major Depressive Disorder Included in Intent-to-Treat Analysesb of Sertraline Versus Placebo in an 8-Week Study

aSustained response was defined as the time at which a subject achieved a CGI improvement score of 1 or 2 that was maintained at least at that level in each subsequent study visit through the end of the trial.

bThe included patients received at least one dose of study medication and had at least one valid rating with the CGI during double-blind treatment .

1. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life: the NIH Consensus Development Conference Statement. Psychopharmacol Bull 1993; 29:87-100Medline, Google Scholar

2. Lebowitz BD, Pearson JL, Schneider LS, Reynolds CF III, Alexopoulos GS, Bruce ML, Conwell Y, Katz IR, Meyers BS, Morrison MF, Mossey J, Niederehe G, Parmelee P: Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life: consensus statement update. JAMA 1997; 278:1186-1190Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Palsson S, Skoog I: The epidemiology of affective disorders in the elderly: a review. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 12(suppl 2):S3-S13Google Scholar

4. Steffens DC, Skoog I, Norton MC, Hart AD, Tschanz JT, Plassman BL, Wyse BW, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Breitner JC: Prevalence of depression and its treatment in an elderly population: the Cache County study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:601-607Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Katona CLE: Depression in Old Age. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1994Google Scholar

6. Blazer D, Swartz M, Woodbury M, Manton KG, Hughes D, George LK: Depressive symptoms and depressive diagnoses in a community population: use of a new procedure for analysis of psychiatric classification. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:1078-1084Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Beekman AT, Copeland JR, Prince MJ: Review of community prevalence of depression in later life. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174:307-311Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Callahan CM, Hui SL, Nieanaber NA, Musick BS, Tierney WM: Longitudinal study of depression and health services use among elderly primary care patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994; 42:833-838Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Henriksson MM, Marttunen MJ, Isometsa ET, Heikkinen ME, Aro HM, Kuoppasalmi KI, Lonnqvist JK: Mental disorders in elderly suicide. Int Psychogeriatr 1995; 7:275-286Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Katz IR: On the inseparability of mental and physical health in aged persons: lessons from depression and medical comorbidity. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1996; 4:1-16Medline, Google Scholar

11. Conwell Y, Lyness JM, Duberstein P, Cox C, Seidlitz L, DiGiorgio A, Caine ED: Completed suicide among older patients in primary care practices: a controlled study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48:23-29Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Newhouse PA: Use of serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors in geriatric depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57:12-22Medline, Google Scholar

13. Nelson JC, Kennedy JS, Pollock BG, Laghrissi-Thode F, Narayan M, Nobler MS, Robin DW, Gergel I, McCafferty J, Roose S: Treatment of major depression with nortriptyline and paroxetine in patients with ischemic heart disease. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1024-1028Abstract, Google Scholar

14. Bondareff W, Alpert M, Friedhoff AJ, Richter EM, Clary CM, Batzar E: Comparison of sertraline and nortriptyline in the treatment of major depressive disorder in late life. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:729-736Link, Google Scholar

15. Kyle CJ, Petersen HE, Overo KF: Comparison of the tolerability and efficacy of citalopram and amitriptyline in elderly depressed patients treated in general practice. Depress Anxiety 1998; 8:147-153Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Alatamura AC, De Novellis F, Guercetti G: Fluoxetine compared with amitriptyline in major depression: a controlled clinical trial. Int J Pharmacol Res 1989; 9:391-396Medline, Google Scholar

17. Feighner JP, Cohn JB: Double-blind comparative trials of fluoxetine and doxepin in geriatric patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1985; 46:20-25Medline, Google Scholar

18. Guillibert E, Pelicier Y, Archambault JC: A double-blind, multicenter study of paroxetine vs clomipramine in depressed elderly patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1989; 350:132-134Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Newhouse PA, Krishnan KR, Doraiswamy PM, Richter EM, Batzer ED, Clary CM: A double-blind comparison of sertraline and fluoxetine in depressed elderly outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:559-568Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Cohn CK, Shrivastava R, Mendels J, Cohn JB, Fabre LF, Claghorn JL, Dessain EC, Itil TM, Lautin A: Double-blind, multicenter comparison of sertraline and amitriptyline in elderly depressed patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1990; 51(suppl B):28-33Google Scholar

21. Weihs KL, Settle E, Batey S, Batey SR, Houser TL, Donahue RMJ, Ascher JA: Comparison of the safety and efficacy of bupropion sustained release and paroxetine in elderly depressed outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:196-202Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56-62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189-198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 218-222Google Scholar

25. Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R: Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull 1993; 29:321-326Medline, Google Scholar

26. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), I: conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992; 30:473-483Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Tollefson GD, Bosomworth JC, Heiligenstein JH, Potvin JH, Holman S (Fluoxetine Collaborative Study Group): A double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of fluoxetine in geriatric patients with major depression. Int Psychogeriatr 1995; 7:89-104Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Hinrichsen GA, Hernandez NA: Factors associated with recovery from and relapse into major depressive disorder in the elderly. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1820-1825Link, Google Scholar

29. Dew MA, Reynolds CF III, Houck PR, Hall M, Buysse DJ, Frank E, Kupfer DJ: Temporal profiles of the course of depression during treatment: predictors of pathways toward recovery in the elderly. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:1016-1024Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Blennow K, Gottfries CG: Neurochemistry of aging, in Geriatric Psychopharmacology. Edited by Nelson JC. New York, Marcel Dekker, 1998, pp 1-25Google Scholar

31. Alexopoulos GS: Anxiety-depression syndromes in old age. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1990; 5:351-353Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Parmelee PA, Katz IR, Lawton MP: Anxiety and its association with depression among institutionalized elderly. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1993; 1:46-58Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Mulsant BH, Reynolds CF, Shear MK, Sweet RA, Miller M: Comorbid anxiety disorders in late-life depression. Anxiety 1996; 2:242-247Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Palmer BW, Jeste DV, Sheikh JI: Anxiety disorders in the elderly: DSM-IV and other barriers to diagnosis and treatment. J Affect Disord 1997; 46:183-190Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Mulsant BH, Pollock B: Treatment-resistant depression in late life. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1998; 11:186-193Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar