Insurance Expenditures on Bipolar Disorder: Clinical and Parity Implications

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study assessed treatment rates and expenditures for behavioral health care by employers and behavioral health care patients in a large national database of employer-sponsored health insurance claims. METHOD: Insurance claims from 1996 from approximately 1.66 million individuals were examined. Average annual charges per person and payments for behavioral health care were calculated along with patient out-of-pocket expenses and inpatient hospital admission rates. Behavioral health care expenditures for bipolar disorder were compared to expenditures for other behavioral health care diagnoses in these same insurance plans. RESULTS: A total of 7.5% of all covered individuals filed a behavioral health care claim. Of those, 3.0% were identified as having bipolar disorder, but they accounted for 12.4% of total plan expenditures. Patients with bipolar disorder incurred annual out-of-pocket expenses of $568, more than double the $232 out-of-pocket expenses incurred by all claimants. The inpatient hospital admission rate for patients with bipolar disorder was also higher (39.1%) compared to 4.5% for all other behavioral health care claimants. Furthermore, annual insurance payments were higher for covered medical services for individuals with bipolar disorder than for patients with other behavioral health care diagnoses. CONCLUSIONS: Bipolar disorder is the most expensive behavioral health care diagnosis, both for patients with bipolar disorder and for their insurance plans. For every behavioral health care dollar spent on outpatient care for patients with bipolar disorder, $1.80 is spent on inpatient care, suggesting that better prevention management could decrease the financial burden of bipolar disorder.

Bipolar disorder occurs in approximately 1% of the U.S. population (1, 2). The chronic recurrent nature of this disorder, with its high level of disability, potentially interferes with sustained individual employment, leading to an expectation of lower prevalence of the disorder among individuals enrolled in employment-based insurance plans (3). Corresponding lower levels of employment-based insurance payments for bipolar disorder, as opposed to other behavioral health care diagnoses, is also be present. In this study, we examined the cost and prevalence of treatment for bipolar disorder among a large population of privately insured individuals and discuss the importance of our findings to employers and treatment providers, as well as health care policy makers.

Method

Data Source

Data consisted of all insurance claims submitted for behavioral health care services (mental health and substance abuse) in 1996 by a group of approximately 1.66 million individuals enrolled in group health insurance through an employer. This national database contains 911 employers with enrollees in all 50 states. These 911 employers were selected for inclusion because they had stable insurance enrollment in calendar year 1996.

These are claims-level billing data. Each claim contains a plan identifier, a patient identifier (scrambled to protect patient confidentiality), the patient’s relationship to the employee (self, spouse, or child), sex, date of birth, dates of incurred service, primary diagnosis by standard ICD-9-CM code, charges, and payments. Data contain information from all processed claims, including claims that were filed but for which no insurance payments were made because the patients had not yet met their plan’s deductible or had exceeded their available benefit. Pharmacy claims were not available; hence, no information was available on the use or cost of medications. In addition to behavioral health care claims, medical claims were available for 862 of the employer’s insurance plans.

Enrollment Status

The relationship between individuals using services to the employee was identified in the data by enrollment status—employee, spouse, child, or other dependent. Only 0.2% of the patients were enrolled as “other dependents,” and of them, more than 90.0% were less than 19 years of age. Therefore, we included all “other dependents” in the child enrollment category, leaving us with three enrollment categories: employee, spouse, and child.

Expenditures

Each claim contained the amount of the actual bill, the amount considered allowable, and the charge covered by the insurance plan. For the purposes of this study, behavioral health care expenditures were considered the covered charges.

Insurance Reimbursements

Only the amounts actually paid to the providers by the insurance plan were designed insurance reimbursements or plan payments. These are payments paid by the insurance plan for behavioral health care services. These amounts included payments for outpatient and inpatient behavioral health care services from licensed providers; they did not include any payments for medications, copayments made by patients, or patient deductible payments.

Out-of-Pocket Payments

We could not directly observe out-of-pocket payments made by patients, such as copayments and deductible payments. As a proxy for these expenditures, we used the difference between total behavioral health care expenditures and insurance reimbursements.

Behavioral Health Care Services

Claims were identified by the insurance plans as behavioral health care services according to primary ICD-9-CM codes as recorded by the provider on submitted claims. Claims for behavioral health care services in these insurance plans are managed separately by a large managed behavioral health care organization.

Identifying Patient Diagnoses

Bipolar disorder and other specific behavioral health care disorders, including substance abuse disorders, mood disorders, anxiety disorders, adjustment disorders, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) were identified with primary ICD-9-CM codes recorded in insurance billing claims. (Codes used are available from the first author.) Individuals were assigned the diagnosis of bipolar disorder if they had at least one claim with a primary ICD-9-CM code for bipolar disorder during the study year, regardless of whether they also had other behavioral health care diagnoses during that year. Individuals with claims for behavioral health care diagnoses other than bipolar disorder were identified with the primary ICD-9-CM codes found on their claims. Because individuals may have multiple claims with different primary behavioral health care diagnoses, categories of behavioral health care disorders were not mutually exclusive.

Admission Rates

We defined an inpatient hospital admission as one that generated a room-and-board charge by a medical facility and was of 24 hours or more. Readmissions to the same facility within 48 hours of discharge were considered a continuation of the original admission—not a separate admission.

Inpatient admission rates were presented as either the overall admission rate (calculated as the total number of admissions in a year for a defined group of patients, divided by the total number of patients in the defined group) or as admission rates specific to bipolar disorder (calculated as the total number of admissions in a year specifically for the treatment of bipolar disorder, divided by the total number of patients with bipolar disorder).

Analysis

Person-level descriptive analysis was performed on the data. Where appropriate, chi-squire or student’s t test was used to determine significance in observed differences among groups of patients. Data access and handling was approved by the University of Pittsburgh’s Institutional Review Board under exempt review.

Results

There were approximately 1.66 million covered individuals; of these, 7.5% (N=124,744) filed at least one insurance claim for a behavioral health care service received in 1996. Only 0.2% (N=3,793) of all covered individuals filed a behavioral health care claim for bipolar disorder.

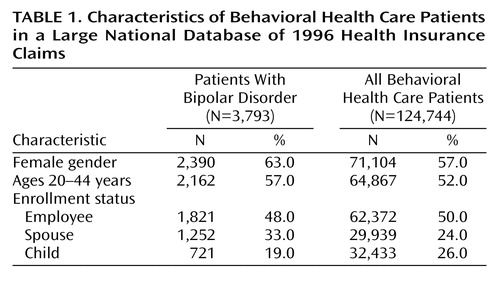

Enrollment Status of Patients With Bipolar Disorder

Of the individuals identified as having bipolar disorder, 48.0% were identified as employees, 33.0% were enrolled as spouses, and the remaining 19.0% were enrolled as children (Table 1). Over one-half of the patients with bipolar disorder (57.0%) were between 20 and 44 years of age. Women accounted for 63.0% of identified patients with bipolar disorder.

Inpatient Hospital Admissions

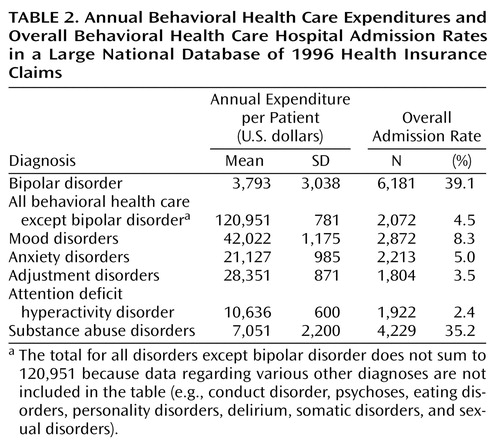

A total of 21.0% (N=797) of all of the bipolar patients identified had at least one behavioral health care hospital admission during 1996, which resulted in an annual inpatient behavioral health care hospital admission rate of 39.1%, surpassing even the 35.2% behavioral health care hospital admission rate for patients with substance abuse diagnoses. Furthermore, they had a high specific bipolar disorder hospital admission rate of 13.3% (N=504). Among patients with bipolar disorder who had a behavioral health care hospital admission during 1996, 6.9% (55 of 797) had more than 30 behavioral health care inpatient days. Table 2 presents a comparison of behavioral health care expenditures and behavioral health care inpatient hospital admission rates between patients with bipolar disorder and patients with other behavioral health care diagnoses.

Behavioral health care hospital admission rates were particularly high among adolescents with bipolar disorder (12–19-year-olds). A total of 39.6% (188 of 475) of the adolescents with bipolar disorder had at least one behavioral health care inpatient hospital admission during the year, and approximately one-half of those had more than one behavioral health care hospital admission during the year, resulting in a high (84.6%, N=402) behavioral health care hospital admission rate for the adolescents with bipolar disorder. Congruent with the fact that multiple hospital admissions are common among adolescents with bipolar disorder who were ever hospitalized, adolescents had more behavioral health care hospital admissions per year than the adult patients with bipolar disorder who were ever hospitalized (rate: 2.14 versus 1.76, respectively).

Among the adults with bipolar disorder, employees experienced significantly fewer (χ2=15.15, df=1, p<0.001) behavioral health care hospital admissions during 1996 than the spouses with bipolar disorder (15.8%, 287 of 1,821, versus 21.2%, 269 of 1,267, respectively).

Behavioral health care hospital admissions were high among the patients with bipolar disorder in our data, but so were medical admissions, indicating high rates of medical comorbidity. Medical insurance claims records were available for 2,910 of the bipolar patients in this study. Among those patients, we observed that 22.0% (N=641) had at least one medical admission during the year compared to 8.6% (N=8,356) of the individuals with all other behavioral health care diagnoses in the same data subset (N=97,167). Furthermore, among the 620 patients with bipolar disorder in this data subset who experienced a behavioral health care hospital admission during the year, 85.0% (527 of 620) also experienced a medical admission during the same calendar year. By comparison, among patients with bipolar disorder with no behavioral health care hospital admissions (N=2,290), only 5% incurred a medical admission during the year. Given the high medical admission rates among patients with bipolar disorder with behavioral health care hospital admissions, it is not surprising that their average medical insurance expenditures were significantly higher (t=17.97, df=769.63, p<0.001) than those for patients with bipolar disorder without behavioral health care hospital admissions ($12,433 versus $3,044 per patient).

Expenditures for Care

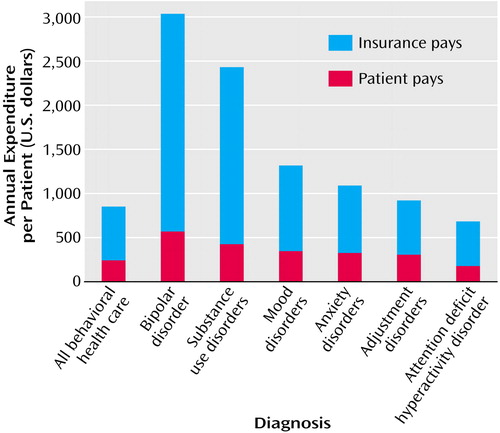

Consistent with the high behavioral health care hospital admission rate we reported, behavioral health care expenditures for patients with bipolar disorder were significantly higher than those for patients with all other behavioral health care diagnoses (t=22.45, df=3,818.78, p<0.001) (Figure 1). A total of 59.9% (N=602) of those with bipolar disorder in the study were high service users of outpatient care as defined by having 20 or more behavioral health care outpatient visits per year.

Insurance plans pay significantly more (t=21.62, df=3,817.50, p<0.001) for behavioral health care for patients with bipolar disorder than for patients with other behavioral health care diagnoses, including substance abuse disorders, mood disorders, anxiety disorders, adjustment disorders, or ADHDs. Insurance plans pay an average of $2,470 per patient per year for behavioral health care for patients with bipolar disorder, a full 400% more per patient per year on average for behavioral health care than for all other claimants. Patients with bipolar disorder themselves pay an estimated $568 out of pocket annually for their care, which significantly surpasses the $232 annual out-of-pocket payments made by patients with all other behavioral health care diagnoses (t=17.57, df=3,830.08, p<0.001). Nonetheless, patients with bipolar disorder bear a lower proportion of their total behavioral health care expenditures, paying 18.7% ($568 of $3,038) of the cost out of pocket compared to 29.7% ($232 of $781) paid by all other behavioral health care patients.

Overall, 3.0% of all behavioral health care patients in our study were treated for bipolar disorder during 1996, but those 3.0% accounted for 12.4% ($9.4 million of $75.8 million) of total behavioral health care expenditures. High expenditures for behavioral health care for patients with bipolar disorder were driven by the disproportionately high use of inpatient care by these patients. For every $1.00 the insurance plans spent for outpatient care for patients with bipolar disorder, $1.80 was spent for inpatient care. Insurers also incurred higher mean annual expenditures for covered medical services for patients with bipolar disorder than for patients with other behavioral health care diagnoses.

Discussion

Given the overall adult incidence of bipolar disorder in the United States, it may appear inconsistent that few enrollees in these employer-sponsored insurance plans (3.0%) were identified as having bipolar disorder. This low prevalence of treatment for bipolar disorder is not unique to this study. Simon and Unutzer (4) reported a similar rate of treatment of bipolar disorder in a large Washington health maintenance organization (HMO) with a large proportion of employment-based enrollees. This level of identification and treatment of bipolar disorder in these plans is not surprising, given that this was not a randomly chosen population sample. This study group represented a large, broad segment of enrollees in an employer-sponsored health insurance plan with behavioral health care coverage. We identified individuals with bipolar disorder by the primary diagnosis code on their insurance claims. Misclassification of patients with bipolar disorder may have occurred, as well as a fundamental underrecognition of bipolar disorder (5). These effects may have underestimated the true number of patients with this clinical diagnosis. Our previous work (6) has suggested that the diagnosis of bipolar disorder by a mental health professional is reliable. Furthermore, more than one-half of the patients identified as having bipolar disorder were enrolled family members rather than employees. In the largest registry of patients with bipolar disorder in the United States (7), only one-third reported being employed. Approximately 13.3% of the patients with bipolar disorder who were identified in our study were adolescents, which supports recent evidence that this disorder is one of early onset (8).

This study captured filed insurance claims, yet behavioral health care expenditures were higher than what has been reported in other studies. In two small studies of veterans (9, 10), Bauer and his colleagues estimated expenditures for behavioral health care (excluding pharmacy costs) for bipolar disorder at $1,749 to $2,557 per patient per year, compared to the average annual behavioral health care expenditure of $3,038 found in this study. These studies estimated behavioral health care expenditures by assigning Veterans Administration cost codes, whereas data reported here are actual expenditures. Simon and Unutzer (4) reported average annual insurance payments of $1,237 for behavioral health care (again, excluding pharmacy costs) for individuals treated for bipolar disorder by an HMO.

Because previous studies were conducted on veterans or on enrollees in an HMO, they did not address out-of-pocket costs for patients. In this study, we found that patients with bipolar disorder paid significantly more out of pocket for their behavioral health care than patients with other behavioral health care diagnoses, including substance abuse disorders, anxiety disorders, adjustment disorders, and mood disorders.

Insurance and Clinical Implications

High overall behavioral health care expenditures for patients with bipolar disorder in this study were a direct result of high behavioral health care hospitalization rates. For every $1.00 spent on outpatient care for these patients, self-insured employers spent $1.80 for inpatient care. This ratio of outpatient to inpatient expense was markedly lower than the 1:7.8 ratio estimated by Wyatt and Henter (11) but not surprising, given that at least one-half of the patients with bipolar disorder in our study were employed at firms enrolling them in insurance plans that included behavioral health care coverage. Yet even in this group of functional patients with bipolar disorder, behavioral health care hospital admission rates were high.

Our findings are in line with recommendations for more comprehensive outpatient management of bipolar disorder, both in the short and the long term. The data support our need to recognize that long-term management strategies that reduce costly hospitalizations represent an important aspect of overall management of bipolar disorder. Such comprehensive treatment might also improve treatment adherence as well as enable individuals to fully restore their level of functioning. Given that many individuals with bipolar disorder were employed in this group, one would expect that such individuals may have been experiencing discrete episodes that allowed them to return to work between episodes. In short, we hope that this study leads to acknowledgment by providers and insurers that providing comprehensive management of bipolar disorder could reduce fiscal and social costs. Furthermore, attention to associated comorbidity of medical and other psychiatric diseases could further reduce overall cost. We cannot discern whether the high use of medical services among this group of patients with bipolar disorder relates to the existence of nonpsychiatric illness or to distress produced by bipolar disorder, which resulted in the presentation of somatic complaints to a primary care provider. However, the question of whether patients with bipolar disorder are at high risk for medical morbidity is an interesting one. Finally, the low prevalence of treatment for bipolar disorder in this group raises the question of whether people in need of treatment for bipolar disorder simply do not receive behavioral health care services.

Implications for Mental Health Parity

Financial parity between behavioral health care and medical coverage has been addressed by many states, but the persistence of service limitations can still result in inadequate access to covered services. Behavioral health care policies commonly have tighter limits on benefits than medical policies with annual limits of 30 inpatient days and 20 outpatient visits common (12, 13). Previous work has shown that parity legislation aimed at removing or reducing limitations on services for behavioral health care insurance would have little effect on most plan enrollees (12). Yet, 59.9% (N=602) of the patients with bipolar disorder in this study exceeded 20 outpatient visits, and 6.9% (N=55) of those with a behavioral health care hospital admission exceeded 30 inpatient days. The patients with bipolar disorder who were most vulnerable to service limitations in this study were children and adolescents. For those under age 21, nearly one-quarter exceeded 20 outpatient visits, and nearly one-half of those hospitalized exceeded 30 inpatient days. This suggests that benefit limitations would have a real effect on enrollees with bipolar disorder and that benefit parity would be particularly important for them.

What’s Next?

The data used in this study provided a unique opportunity to assess the direct financial burden of behavioral health care services on individuals with bipolar disorder who were enrolled in a commercial insurance plan, but they did not provide the necessary link between the use of services and disease outcome. Many of the behavioral health care hospital admissions for patients with bipolar disorder were attributed to behavioral health care conditions other than bipolar disorder, and almost all patients with bipolar disorder with behavioral health care hospital admissions experienced medical admissions as well. These findings suggest that individuals with bipolar disorder suffer a high rate of comorbidity with other behavioral health care conditions as well as medical comorbidities that merit further investigation.

|

|

Presented in part at the Fourth International Conference on Bipolar Disorder, Pittsburgh, June 14–16, 2001. Received Feb. 11, 2002; revisions received Sept. 17 and Dec. 27, 2002; accepted Jan. 13, 2003. From the Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh. Address reprint requests to Dr. Peele, 130 DeSoto St., GSPH: A649, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15261; [email protected] (e-mail). Funded by grants from NIMH (MH-56925) and the Mental Health Intervention Research Center (MH-30915). The authors thank Magellan Behavioral Health for the data.

Figure 1. Sources of Payment for Selected Behavioral Health Care Diagnoses in a Large National Database of 1996 Health Insurance Claims

1. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:85-94Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, Rubinow DR, Holmes C, Abelson JM, Zhao S: The epidemiology of DSM-III-R bipolar disorder in a general population survey. Psychol Med 1997; 27:1079-1089Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Murray CJL, Lopez AD: The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability From Disease, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard School of Public Health on Behalf of the World Health Organization and the World Bank, 1996Google Scholar

4. Simon GE, Unutzer J: Health care utilization and costs among patients treated for bipolar disorder in an insured population. Psychiatr Serv 1999; 50:1303-1308Link, Google Scholar

5. Angst J, Gamma A: Prevalence of bipolar disorders: traditional and novel approaches. Clinical Approaches in Bipolar Disorder 2002; 1:10-14Google Scholar

6. Cluss PA, Marcus SC, Kelleher KJ, Thase ME, Arvay LA, Kupfer DJ: Diagnostic certainty of a voluntary bipolar disorder case registry. J Affect Disord 1999; 52:93-99Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Scholle SH, Peele PB, Kelleher KJ, Frank E, Jansen-McWilliams L, Kupfer DJ: Effect of different recruitment sources on the composition of a bipolar disorder case registry. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2000; 35:220-227Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Grochocinski VJ, Cluss PA, Houck PR, Stapf DA: Demographic and clinical characteristics of individuals in a bipolar disorder case registry. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:120-125Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Bauer MS, Shea N, McBride L, Gavin C: Predictors of service utilization in veterans with bipolar disorder: a prospective study. J Affect Disord 1997; 44:159-168Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Bauer MS, Kirk GF, Gavin C, Williford WO: Determinants of functional outcome and healthcare costs in bipolar disorder: a high-intensity follow-up study. J Affect Disord 2001; 65:231-241Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Wyatt RJ, Henter I: An economic evaluation of manic-depressive illness—1991. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1995; 30:213-219Medline, Google Scholar

12. Peele PB, Lave JL, Y Xu: Benefit limitations in behavioral health carve-outs: do they matter? J Behav Health Serv Res 1999; 26:430-441Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Sturm R: How expensive is unlimited mental health care coverage under managed care? JAMA 1997; 12:1533-1537Crossref, Google Scholar