Self-Help for Bulimia Nervosa: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors examined the effectiveness of unguided self-help as a first step in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. METHOD: A total of 85 women with bulimia nervosa who were on a waiting list for treatment at a hospital-based clinic participated. The patients were randomly assigned to receive one of two self-help manuals or to a waiting list control condition for 8 weeks. One of the self-help manuals addressed the specific symptoms of bulimia nervosa (cognitive behavior self-help), while the other focused on self-assertion skills (nonspecific self-help). RESULTS: Twenty patients (23.5%) dropped out of the study. The data were analyzed with intention-to-treat analysis. Although the group-by-time interaction for binge eating and purging was not statistically significant, simple effects showed that there was a significant reduction in symptom frequency in both self-help conditions at posttreatment but not in the waiting list condition. There were no statistically significant changes in levels of dietary restraint, eating concerns, concerns about shape and weight, or general psychopathology. A greater proportion of patients in the cognitive behavior self-help (53.6%) and nonspecific self-help (50.0%) conditions reported at least a 50% reduction in binge eating or purging at posttreatment, compared with the waiting list condition (31.0%). A lower baseline knowledge about eating disorders, more problems with intimacy, and higher compulsivity scores predicted a better response. CONCLUSIONS: The findings suggest that a subgroup of patients with bulimia nervosa may benefit from unguided self-help as a first step in their treatment. Cognitive behavior self-help and nonspecific self-help had equivalent effects.

Accumulating research evidence suggests that self-help manuals used either independently or in combination with guidance and support from a therapist are beneficial for a significant subgroup of patients with bulimia nervosa. In two case series, Cooper and colleagues (1, 2) obtained substantial reductions in the frequency of binge eating and vomiting after guided use of a cognitive behavior self-help manual (3) for 4 months. The guidance involved six to eight brief sessions with a nonspecialist therapist who provided support and encouragement in the use of the manual. Treasure and colleagues (4, 5) reported that one-third of the patients who were asked to follow a self-help manual (6) independently for 8 weeks experienced a significant improvement in binge eating and purging that was maintained at the 18-month follow-up. Using the same self-help manual, Thiels and colleagues (7) found that eight biweekly sessions of guided self-help was equivalent to 16 weekly sessions of individual cognitive behavior therapy in terms of rates of remission from binge eating and purging at a 1-year follow-up. Finally, Mitchell and colleagues (8) found that combining fluoxetine with a self-help manual produced better results than fluoxetine alone.

Attempts to identify the characteristics of a subgroup of patients with bulimia nervosa who respond to self-help suggest that less severe cases are more likely to benefit. In studies to date, the following pretreatment variables have been associated with lack of response to self-help interventions: a history of anorexia nervosa (2), more frequent binge eating at baseline (9, 10), more intense concerns about shape and weight (11), comorbid personality disorder (2), and higher levels of general psychopathology (12).

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a cognitive behavior self-help manual for patients with bulimia nervosa who were on a waiting list for treatment at a hospital-based specialist clinic. One of the limitations of previous self-help studies is that none have included attention-placebo control conditions designed to control for nonspecific factors, such as receiving a self-help manual, hearing a plausible rationale, and expecting to improve. The present study addressed this limitation by including a control self-help manual that focused on assertiveness skills but did not address the specific symptoms of the eating disorder. A second aim of the study was to identify predictors of outcome.

Method

Study Design

A total of 85 women who met DSM-IV criteria for bulimia nervosa were randomly assigned to one of three experimental conditions for 8 weeks: one of two different self-help programs or a waiting list control condition. The first self-help condition (cognitive behavior self-help) involved following the self-help manual Overcoming Binge Eating(13). This self-help manual is based on the cognitive behavior approach to the treatment of binge eating and bulimia nervosa (14). It contains both psychoeducational material and basic behavioral strategies designed to address specific eating disorder symptoms. The second self-help condition (nonspecific self-help) was designed to control for nonspecific factors, such as receiving a self-help book, hearing a plausible rationale, and expecting to improve. It involved following the self-help manual Self-Assertion for Women(15). This self-help manual focuses on developing assertiveness skills and does not in any way address the specific symptoms of bulimia nervosa. This control intervention was selected because it might be regarded by patients as a credible alternative treatment, since many women with eating disorders report experiencing significant interpersonal difficulties, including inhibited self-assertion. Like the cognitive behavior self-help manual, the nonspecific self-help book contains both psychoeducational information and practical advice designed to foster behavioral change. Both books were similar in length and level of difficulty. Individuals assigned to the waiting list condition received no intervention. Blind assessments took place immediately before and after treatment.

Patients and Recruitment

Eighty-five patients who met diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa as operationally defined by the Eating Disorder Examination (16, 17) and were seeking specialized treatment for the first time took part in the study. The participants were recruited from among those on a waiting list for treatment at an eating disorders clinic in a large general hospital. The patients whose letters of referral suggested that they were suitable for the study were sent a letter that briefly described the study and stated that a research assistant would be telephoning them to find out if they were eligible to take part. Potential participants received a brief telephone screening interview that assessed the study inclusion and exclusion criteria. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) younger than age 17, 2) pregnant, 3) medical illness or treatment known to influence eating or weight (e.g., diabetes mellitus), 4) current or previous specialist treatment for an eating disorder, and 5) body mass index (kg/m2) under 18. Patients who were taking an established dose of antidepressant medication were eligible to take part.

Of 245 patients screened, 123 appeared eligible and were invited for a formal assessment interview. The main reasons for exclusion at telephone screening were absence of binge eating symptoms, binge eating/purging symptoms less than once weekly, episodes of overeating not objectively large (by definition of the Eating Disorder Examination), and lack of interest in the study. Of note, we used a threshold frequency of once per week for binge eating and compensatory behaviors rather than the twice-weekly threshold specified in DSM-IV. This is because the twice-weekly threshold is arbitrary. No significant differences have been found between those who binge eat and purge on average once per week compared with those who have more frequent symptoms (18, 19). Of the 123 eligible patients, 89 attended the assessment interview. The main reasons that the remaining 34 patients did not attend the initial assessment were 1) lack of interest or time, 2) living too far away, and 3) seeking treatment elsewhere. At this appointment, a complete description of the study was provided, and written informed consent was obtained. It was explained that the purpose of the study was to compare two self-help programs for women with eating disorders, one focusing on eating behavior and the other focusing on interpersonal issues. Potential participants were also told that if they decided to take part in the study, they would be randomly assigned to one of three conditions, one of which was a waiting list control condition. Of those who attended the assessment interview, four were excluded, three because their episodes of overeating were not objectively large and one because she was pregnant. This resulted in a final sample size of 85 participants.

A restricted randomization procedure employing random permuted blocks of three people was used to ensure approximately equal numbers of participants in the three conditions. The randomization list was prepared with a table of random numbers and transferred to a numbered sequence of opaque sealed envelopes by a research assistant who was not involved in carrying out the study. After each initial assessment interview, the next envelope in the sequence was opened. Neither the interviewer nor the patient knew the treatment assignment until after the assessment had been completed.

Assessment Protocol and Measures

The initial assessment interview lasted approximately 90 minutes. We assessed key eating disorder symptoms using the diagnostic items of the Eating Disorder Examination. Measures derived from this interview included the frequency of objective binge episodes, self-induced vomiting, laxative and diuretic misuse, and intense exercise; degree of concern about shape and weight; and dietary restriction. We measured other eating disorder features using the fourth edition of the self-report version of the Eating Disorder Examination (20) and the Eating Disorder Inventory (21). In addition, weight and height were measured in order to calculate body mass index (kg/m2). We measured aspects of general psychopathology using the Beck Depression Inventory (22), the Beck Anxiety Inventory (23), and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (24). We assessed interpersonal functioning using the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (25), and we measured personality disturbance using the Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology—Basic Questionnaire (26). Two separate true/false questionnaires (one 12-item and one 13-item) were developed to measure the participants’ knowledge of the psychoeducational contents of the two self-help manuals (nonspecific knowledge and cognitive behavior knowledge).

After completing all of the above measures, the patients were informed of their treatment assignments. The nature of the self-help program they would be receiving was described to those randomly assigned to one of the two self-help conditions. They were asked to do their best to read the book and follow the advice contained in it over the next 2 months. Next, they were asked to complete a measure of their expectations concerning the suitability and likely effectiveness of the self-help program they had received. This consisted of two 10-cm visual analogue scales whose poles were labeled “not at all” and “extremely.”

An assessor who was blind to the patients’ treatment assignment performed the posttreatment assessments 8 weeks later. The diagnostic items of the Eating Disorder Examination were readministered together with the Eating Disorder Examination, 4th ed., the Eating Disorder Inventory, the Beck Depression Inventory, the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems, and both knowledge questionnaires. In addition, a brief interview was used to measure compliance with the self-help program. This semistructured interview asked participants what proportion of the self-help manual they had read and whether or not they had completed the practical exercises contained in the manual (for example, self-monitoring).

Statistical Analyses

The primary outcome variables were the frequencies of objective binge eating and compensatory behaviors (i.e., self-induced vomiting, laxative and diuretic misuse, intense exercise, and dietary restraint) as assessed by the Eating Disorder Examination interview. Secondary outcome measures included other eating disorder features (Eating Disorder Examination, 4th ed., global scores and Eating Disorder Inventory subscale scores), knowledge scores, self-esteem ratings (Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale score), depression ratings (Beck Depression Inventory score), and interpersonal problems ratings (Inventory of Interpersonal Problems score). The binge eating and purging data were positively skewed and were therefore logarithmically transformed before analysis.

The data were analyzed with intention to treat. We examined two methods of data imputation for missing posttreatment data. The first method involved carrying forward the pretreatment value on the basis of the rationale that a group from a tertiary care clinic is unlikely to improve in the absence of treatment. The second method was multiple imputation by using the procedure recommended by Yuan (27). Missing values were imputed by using both a simple regression equation as well as a more advanced model employing treatment condition and duration of illness as covariates in addition to pretreatment scores. The findings were the same regardless of the method used. The results reported in this article are based on the first method.

The three conditions were compared on the outcome measures by using two-by-three (pretreatment versus posttreatment by cognitive behavior self-help versus nonspecific self-help versus waiting list) repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Significant results were followed by the appropriate post hoc comparisons (i.e., paired t tests and one-way ANOVAs followed by between-groups t tests) with alpha set at 0.01. For binge eating and purging, the simple effects of self-help or waiting list control groups were examined because we had specific focused hypotheses about the effects of self-help within each group. Next, Pearson’s chi-square tests were used to compare the proportions of participants in each condition who were classified as responders. Response was defined as a reduction of at least 50% in the frequency of binge eating or purging. To identify the characteristics of responders, logistic regression analysis was used to examine whether baseline characteristics (including personality disturbance) or self-help condition predicted outcome. In all cases, two-tailed tests were used.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The mean age of the 85 participants was 27 years (SD=8, range=17–53). The majority of the participants (93%) were of the purging subtype (i.e., they used self-induced vomiting or laxative or diuretic misuse to compensate for binge eating). On average, the participants reported 28 episodes of objective binge eating (SD=23, range=4–112) and 41 episodes of purging (SD=35, range=0–112) over the previous 4 weeks. They were of normal body weight on average, with a mean body mass index of 23 kg/m2 (SD=5, range=18–41). The average age at onset of regular binge eating and compensatory behavior was 19 years (SD=6, range=10–38 years), and the average duration of regular binge eating and compensatory behavior was 7 years (SD=6, range=6 months to 33 years). A total of 71% were single, 22% were married or cohabiting, 6% were divorced, and 1% were widowed. The ethnic distribution of the group was 83% Caucasian, 2% African Caribbean, 7% Asian, and 8% other. The baseline characteristics of the group were similar to those reported in other treatment studies (e.g., references 27–29).

Random Assignment

At baseline, the patients in the three treatment conditions were similar in terms of age, age at onset of illness, duration of bulimia nervosa, frequency of binge eating, and scores on the assessment measures. However, the waiting list control group reported a significantly higher baseline frequency of purging compared with the other two groups. Therefore, baseline purge frequency was employed as a covariate for all ensuing analyses. There were also no significant differences between the cognitive behavior self-help group and the nonspecific self-help group with regard to the participants’ ratings of the suitability (for cognitive behavior: mean=6.7, SD=2.2; for nonspecific: mean=6.3, SD=1.7) and expected effectiveness (for cognitive behavior: mean=4.8, SD=2.5; for nonspecific, mean=5.7, SD=2.1) of the self-help programs.

Attrition

Twenty participants (23.5%) dropped out of the study and did not attend the posttreatment assessment: five (17.9%) of these were from the cognitive behavior self-help group (N=28), seven (25.0%) were from the nonspecific self-help group (N=28), and eight (27.6%) were from the waiting list control group (N=29). There was no statistically significant difference between the three conditions in terms of the rate of attrition. This dropout rate is similar to those reported in previous treatment studies (e.g., references 27–29). There were no significant differences between the dropouts and completers in terms of baseline characteristics.

Response to Treatment: Intention-to-Treat Analyses

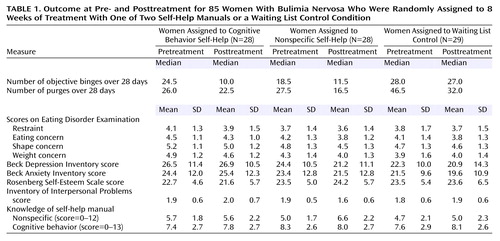

Data on the outcome measures at pre- and posttreatment are presented in Table 1.

Key eating disorder behaviors

The two-by-three repeated-measures ANCOVA for binge eating yielded a significant main effect of time (F=20.2, df=1, 82, p<0.0001), but the main effect of treatment condition and the time-by-treatment interaction were not statistically significant. An examination of the simple effect of time revealed a significant decrease in binge eating from pre- to posttreatment in both cognitive behavior self-help (t=3.0, df=27, p=0.006) and nonspecific self-help (t=2.9, df=27, p=0.008) groups but not in the waiting list control group.

A similar pattern of results emerged for the frequency of purging (i.e., self-inducing vomiting and laxative and diuretic misuse). A one-way ANCOVA was performed, with pretreatment purge frequency employed as a covariate and posttreatment purge frequency used as the dependent variable. The effect of treatment condition was not statistically significant. An examination of the simple effect of time revealed a significant reduction in purge frequency in the nonspecific self-help (t=3.1, df=22, p=0.005) and cognitive behavior self-help (t=2.1, df=26, p=0.04) groups. There was no significant change over time in the waiting list control group.

Patients who reported at least a 50% reduction in binge eating or purging at the posttreatment assessment were classified as responders. The proportions of responders in each condition were 53.6% of the cognitive behavior self-help group (N=15), 50.0% of the nonspecific self-help group (N=14), and 31.0% of the waiting list control group (N=9). The difference between the cognitive behavior group and the waiting list group (χ2=2.6, df=1, N=56, p=0.10) and the difference between the nonspecific self-help group and the waiting list group (χ2=3.1, df=1, N=53, p=0.08) approached statistical significance. The difference between the nonspecific self-help group and the cognitive behavior self-help group was not statistically significant.

Severity of other eating disorder features

The repeated-measures ANOVA for intense exercising revealed a statistically significant time-by-treatment interaction (F=3.4, df=2, 82, p=0.04). Post hoc comparisons showed that intense exercising decreased significantly from pretreatment to posttreatment in the cognitive behavior self-help group (t=2.5, df=27, p=0.01) but not in the nonspecific self-help or waiting list groups. There were no statistically significant changes in the level of dietary restraint, eating concern, or concern about shape or weight as measured by the Eating Disorder Examination, 4th ed., and no statistically significant changes in Eating Disorder Inventory subscale scores.

General psychopathology

There were no statistically significant changes in depression (Beck Depression Inventory), anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory), self-esteem (Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale), or interpersonal problems (Inventory of Interpersonal Problems) scores.

Knowledge

The repeated-measures ANOVA for nonspecific knowledge (i.e., from the self-assertion manual) revealed a statistically significant time-by-treatment interaction (F=4.2, df=2, 78, p=0.02). Post hoc comparisons indicated that nonspecific knowledge increased significantly from pretreatment to posttreatment in the nonspecific self-help group (t=3.1, df=26, p=0.005) but not in the cognitive behavior self-help or waiting list groups. There were no statistically significant changes in specific knowledge (i.e., from the cognitive behavior manual).

Response to Treatment: Completer Analyses

These analyses were repeated with the group restricted to those who had completed the study. The results were unchanged, with one exception. The group-by-time interaction for the Beck Depression Inventory approached statistical significance (F=2.8, df=2, 60, p=0.07).

Compliance

In the cognitive behavior self-help group, the patients reported reading an average of 78% of the self-help manual in comparison with 59% of the manual in the nonspecific self-help group (t=2.8, df=36, p=0.09). In terms of compliance with the behavioral exercises recommended in the manuals, 28.6% (eight of 28) of the cognitive behavior self-help group, compared with 21.4% (six of 28) of the nonspecific self-help group, indicated that they had completed the exercises (χ2=1.1, df=1, N=54, p=0.77). Those who complied with the behavioral exercises were more likely to be classified as responders than those who did not (χ2=11.2, df=1, N=51, p=0.01).

Characteristics of responders

To examine predictors of outcome, the baseline characteristics of responders and nonresponders in the two self-help groups were first compared by using a series of t tests. Four significant differences emerged: compared to nonresponders, responders had higher Eating Disorder Inventory perfectionism scores (t=2.2, df=50, p=0.03), higher Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology compulsivity scores (t=2.0, df=49, p=0.04), higher Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology intimacy problems scores (t=2.4, df=49, p=0.02), and lower cognitive behavior knowledge scores (t=2.3, df=49, p=0.03). These four variables together with treatment condition were then entered into a standard logistic regression analysis. A dichotomous measure of compliance, whether or not participants completed the behavioral exercises in the self-help manual, was forced into the regression equation first (Wald χ2=3.9, df=1, odds ratio=0.87, R2=0.02, p=0.04). Intimacy problems (Wald χ2=5.7, df=1, odds ratio=1.1, R2=0.05, p=0.02), cognitive behavior knowledge scores (Wald χ2=5.2, df=1, odds ratio=0.72, R2=0.04, p=0.02), and Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology compulsivity scores (Wald χ2=4.3, df=1, odds ratio=1.1, R2=0.05, p=0.02) emerged as significant predictors of treatment response. Lower baseline knowledge about eating disorders, more problems with intimacy, and higher compulsivity scores predicted better response. Self-help condition was not a significant predictor of outcome.

Discussion

This aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a cognitive behavior self-help manual for patients with bulimia nervosa who were on a waiting list for treatment at a hospital-based specialist clinic. A particular strength of the study design was that it included an attention-placebo control condition designed to control nonspecific factors (i.e., receiving a self-help book, hearing a plausible rationale, and expecting to improve). The finding that patients gave equivalent ratings to the two self-help conditions in terms of suitability and likely effectiveness suggests that the nonspecific self-help manual was a credible control treatment. The results of the study indicate that both self-help interventions produced modest reductions in the primary behavioral symptoms of binge eating and purging for a subgroup of the participants. This was not accompanied by parallel changes in other eating disorder features, such as dietary restraint or concern about shape and weight, nor was it associated with improvements in general psychopathology, such as depression or self-esteem. In addition, there was no significant overall improvement in knowledge about eating disorders. A limitation of the study is that only 69.1% of those who appeared eligible to take part, according to the telephone screening interview, agreed to participate. This may limit the generalizability of the findings.

The effect sizes observed in this study were relatively small in comparison with previous studies (e.g., references 2, 7, 12). One possible reason for this may be the conservative method we chose for the intent-to-treat analysis. Given that the participants were tertiary referrals on a waiting list for specialist treatment, it was assumed that their eating disorder symptoms would be unlikely to change in the absence of treatment. Two previous studies found that guided self-help was significantly more effective than unguided self-help, even when the guidance was provided by nonspecialists (12, 30). The effect sizes might have been larger if the participants had received some form of guidance.

The predictor analyses indicated that the patients with less baseline knowledge about eating disorders and greater difficulties with intimacy were more likely to benefit, after control for compliance. Perhaps, for patients who are treatment naive, a self-help manual may be a useful means of conveying educational information and basic practical advice. The unguided self-help format may be particularly well suited to those with intimacy problems, while patients with better interpersonal functioning may benefit more from human contact to support behavioral change. Responders also had higher compulsivity and higher perfectionism scores. Such patients may have been more likely to have read the self-help book and complied with the advice contained in it. In contrast to previous studies, indicators of illness severity were not predictive of outcome in this study.

One possible explanation for the findings is that the observed changes were due to nonspecific factors, such as expecting to improve or experiencing an greater sense of hope. Another possibility is that both self-help interventions exerted an equivalent, albeit modest, effect through different mechanisms of action. The cognitive behavior self-help manual may have exerted its effect on the specific symptoms of bulimia nervosa directly, whereas the nonspecific self-help manual may have had an indirect effect by means of changes in interpersonal skills. Our finding that behavioral change occurred in the absence of attitudinal change is consistent with previous studies on the time course of change with cognitive behavior therapy for bulimia nervosa. It has been shown that most of the behavioral change typically occurs within the first 4 weeks of treatment, with a time lag for attitudinal change (31, 32).

Given the current shortage of specialist treatment services for the treatment of eating disorders, significant wait times are common. Our findings support the idea of offering a self-help manual to patients with bulimia nervosa who are on a waiting list for specialist treatment as part of a stepped-care approach to treatment delivery, since a subgroup may benefit from this type of intervention (33). A self-help manual may be a useful means of delivering psychoeducational information to treatment-naive patients and may be associated with modest improvements in core symptoms for a subgroup.

|

Presented in part at the sixth annual meeting of the Eating Disorders Research Society, Prien, Germany, Nov. 9–12, 2000. Received July 6, 2001; revisions received July 16 and Oct. 17, 2002; accepted Nov. 13, 2002. From the Department of Psychiatry, Toronto General Hospital; and the University Health Network, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Address reprint requests to Dr. Carter, Department of Psychiatry, Toronto General Hospital, 200 Elizabeth St., Eaton Wing 8-231, Toronto, Ont. M5G 2C4, Canada; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a grant from the Dean’s Fund, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto. The authors thank Dr. Robert Cribbie, Ms. Elizabeth Blackmore, and Ms. Kalam Sutandar-Pinnock for assistance with data analysis and Dr. Gary Rodin for comments on the manuscript.

1. Cooper PJ, Coker S, Fleming C: Self-help for bulimia nervosa: a preliminary report. Int J Eat Disord 1994; 16:401-404Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Cooper PJ, Coker S, Fleming C: An evaluation of the efficacy of supervised cognitive behavioral self-help for bulimia nervosa. J Psychosom Res 1996; 40:281-287Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Cooper PJ: Bulimia Nervosa: A Guide to Recovery. London, Robinson, 1993Google Scholar

4. Schmidt U, Tiller J, Treasure J: Self-treatment of bulimia nervosa: a pilot study. Int J Eat Disord 1993; 13:273-277Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Treasure J, Schmidt U, Troop N, Tiller J, Todd G, Turnbull S: Sequential treatment for bulimia nervosa incorporating a self-care manual. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168:94-98Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Schmidt U, Treasure J: Getting Better Bite by Bite. Hove, East Sussex, UK, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1993Google Scholar

7. Thiels C, Schmidt U, Treasure J, Garthe R, Troop N: Guided self-change for bulimia nervosa incorporating use of a self-care manual. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:947-953Link, Google Scholar

8. Mitchell JE, Fletcher L, Hanson K, Mussell MP, Seim H, Al-Banna M: The relative efficacy of fluoxetine and manual-based self-help in the treatment of outpatients with bulimia nervosa. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001; 21:298-304Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Turnbull SJ, Schmidt U, Troop NA, Tiller J, Todd G, Treasure JL: Predictors of outcome for two short treatments for bulimia nervosa: short and long-term. Int J Eat Disord 1997; 21:17-22Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Thiels C, Schmidt U, Troop N, Treasure J, Garthe R: Binge frequency predicts outcome in guided self-care treatment of bulimia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Rev 2000; 8:272-278Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Troop N, Schmidt U, Tiller J, Todd G, Keilen M, Treasure J: Compliance with a self-care manual for bulimia nervosa: predictors and outcome. Br J Clin Psychol 1996; 35:435-438Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Loeb KL, Wilson GT, Gilbert JS, Labouvie E: Guided and unguided self-help for binge eating. Behav Res Ther 1999; 38:259-272Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Fairburn CG: Overcoming Binge Eating. New York, Guilford, 1995Google Scholar

14. Fairburn CG, Marcus MD, Wilson GT: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for binge eating and bulimia nervosa: a comprehensive treatment manual, in Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment and Treatment. Edited by Fairburn CG, Wilson GT. New York, Guilford, 1993, pp 361-404Google Scholar

15. Butler PE: Self-Assertion for Women. New York, HarperCollins, 1992Google Scholar

16. Cooper Z, Fairburn CG: The Eating Disorder Examination: a semi-structured interview for the assessment of the specific psychopathology of eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 1987; 6:1-8Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z: The Eating Disorder Examination, 12th ed, in Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment and Treatment. Edited by Fairburn CG, Wilson GT. New York, Guilford, 1993, pp 317-360Google Scholar

18. Garfinkel PE, Lin E, Goering P, Spegg C, Goldbloom DS, Kennedy S, Kaplan AS, Woodside DB: Bulimia nervosa in a Canadian community sample: prevalence and comparison of subgroups. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1052-1058Link, Google Scholar

19. Wilson GT, Eldredge KL: Frequency of binge eating in bulimic patients: diagnostic validity. Int J Eat Disord 1991; 10:557-561Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ: Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord 1994; 16:363-370Medline, Google Scholar

21. Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Polivy J: Development and validation of a multidimensional Eating Disorder Inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Int J Eat Disord 1983; 2:15-24Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561-571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Beck AT, Steer RA: Beck Anxiety Inventory. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1993Google Scholar

24. Rosenberg M: Conceiving of the Self. New York, Basic Books, 1979Google Scholar

25. Horowitz LM, Rosenberg SE, Baer BA, Ureno G, Villasenor VS: Inventory of Interpersonal Problems: psychometric properties and clinical applications. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988; 56:885-892Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Livesley WJ, Jackson DW, Schroeder ML: Dimensions of personality pathology. Can J Psychiatry 1991; 36:557-562Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Yuan YC: Multiple Imputation for Missing Data: Concepts and New Development. Rockville, Md, SAS Institute, 2002Google Scholar

28. Fairburn CG, Jones R, Peveler RC, Carr SJ, Solomon RA, O’Connor ME, Burton J, Hope RA: Three psychological treatments for bulimia nervosa: a comparative trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:463-469Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Walsh BT, Wilson GT, Loeb KL, Devlin MJ, Pike KM, Roose SP, Fleiss J, Waternaux C: Medication and psychotherapy in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:523-531Link, Google Scholar

30. Agras WS, Walsh BT, Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, Kraemer HC: A multicenter comparison of cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy for bulimia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:459-466Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Wilson GT, Vitousek KM, Loeb KL: Stepped care treatment for eating disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000; 68:564-572Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Wilson GT: Rapid response to cognitive behavior therapy. Clin Psychol Sci and Practice 1999; 6:289-292Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Carter JC, Fairburn CG: Cognitive-behavioral self-help for binge eating disorder: a controlled effectiveness study. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998; 66:616-623Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar