The Intermediate-Term Outcome of Chinese Patients With Anorexia Nervosa in Hong Kong

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors determined the intermediate-term outcome of anorexia nervosa for Chinese patients in Hong Kong. METHOD: A consecutive series of 88 patients who fulfilled DSM-III-R criteria for typical (i.e., fat phobic [N=63]) and atypical (i.e., no fat phobia [N=25]) anorexia nervosa were contacted at least 4 years after onset of their illness for semistructured and self-rated assessments of outcome. RESULTS: Three patients (3.4%) died; the mortality ratio for this group against the expected standard for subjects of similar age and gender was 10.5 to 1. Eighty (94.1%) of the remaining 85 patients were successfully traced 9.0 years after onset of their illness. Good, intermediate, and poor outcomes were seen in 61.8%, 32.9%, and 5.3% of the subjects, respectively. Anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or eating disorder not otherwise specified was exhibited by 55.0% of the subjects (N=44). Lifetime depressive (81.6%) and anxiety (27.6%) disorders were common. Older age at onset and the presence of fat phobia independently predicted poor outcome. Patients with atypical anorexia nervosa were symptomatically stable, less likely to demonstrate bulimia, and had a better eating disorder outcome than patients with typical anorexia nervosa. CONCLUSIONS: The outcome profile of Chinese patients supported the cross-cultural disease validity of anorexia nervosa. The cultural fear of fatness not only shaped the manifest content but also added to the chronicity of the illness.

Since a decade ago, anorexia nervosa has become an increasingly common clinical problem among young women in Hong Kong and other high-income Asian societies such as Japan, Singapore, and Taiwan. To a lesser extent, it has also appeared in the urban regions of low- and medium-low-income Asian countries such as China, India, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia, as well as in Eastern Europe and South America (1). Since treatment resources are very limited, the outcome of anorexia nervosa remains obscure in these countries.

Intermediate- and long-term Western outcome studies have revealed that the morbidity and mortality of anorexia nervosa are considerable (2–6). An outcome study in a Chinese community is of interest for several reasons. First, it may shed light on the disease validity of anorexia nervosa, since the illness has exhibited variations over time and place that make its ontology a subject of controversy (1). If sociocultural factors merely shape its manifest content but not its core, we may expect it to exhibit a cross-culturally similar outcome. Second, since atypical anorexia nervosa (i.e., anorexia without the fear of fatness or “fat phobia”) still occurs in Hong Kong (1), an outcome study using a broadened disease definition that encompasses both typical and atypical anorexia nervosa can clarify whether the identity of the illness has “changed” in response to sociocultural forces (7). Third, such a study may reveal cross-culturally applicable outcome predictors of anorexia nervosa.

Method

Subjects

We defined the onset of illness as the point in time when subjects exhibited weight loss of 15% or more of their expected weight and the absence of three consecutive menstrual cycles. Duration of illness referred to the period from the onset of illness to the time of first clinical presentation to medical practitioners. Our subjects were a consecutive group of patients with an onset of illness at least 4 years before the study who had been seen at the psychiatric and eating disorders clinics of a university-affiliated general hospital from May 1984 to July 2000. This group included 88 Chinese female patients who fulfilled DSM-III-R criteria for typical (N=63) and atypical (N=25) anorexia nervosa. This latter group of subjects satisfied all the diagnostic criteria for typical anorexia nervosa except that their rationales for explaining food refusal and weight loss did not include fat phobia (1). The baseline characteristics of the 88 patients are shown in Table 1. In terms of anorexic subtype, 67.0% (N=59) were restrictive, and 33.0% (N=29) were bulimic. Sixty-four patients (72.7%) had been hospitalized because of the illness. Half of the group (N=44) identified themselves as Christian, and 48.9% (N=43) reported that they had no religion; 1.1% (N=1) of the subjects were Buddhist. In terms of socioeconomic status, subjects were placed into one of five social classes as defined by the U.K. Registrar General’s classification of paternal occupation (8) (class I: 5.7% [N=5]; class II: 9.1% [N=8]; class III: 27.3% [N=24]; class IV: 47.7% [N=42]; class V: 10.2% [N=9]).

Three subjects died. Of the 85 living subjects, two refused our study, and three could not be traced but were confirmed alive by the Government Death Registry. Thus, 80 subjects were successfully studied at an average duration of 9.0 years (SD=5.2) after onset of their illness. Written informed consent was obtained. All subjects underwent a semistructured interview, and 74 participants completed self-rated scales. The baseline features of these 74 subjects did not differ from the six subjects who did not complete self-rated scales. The research protocol was approved by the institutional review board.

Procedure

The interview assessed subjects’ disordered eating attitudes and behaviors as well as weight, height, and menstrual status. It also included Chinese versions of the Morgan-Russell Outcome Assessment Schedule (9), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (10), and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (11). The research assistant (Y.Y.L.C.) was blind to the presence or absence of fat phobia of subjects at baseline. Between this assistant and the principal investigator (S.L., an eating disorder specialist), the overall kappas for agreement on the Morgan-Russell Outcome Assessment Schedule and SCID were 0.99 and 0.90, respectively, and the intraclass coefficient of agreement for the Hamilton depression scale was 0.99.

The self-rated scales were in Chinese. They covered both specific and general psychopathology. The former included the Eating Disorder Inventory-1 (12), Eating Attitudes Test-26 (13), and the questionnaire version of the Eating Disorder Examination (14). The general scales included the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (15, 16), SCL-90 (17), Beck Depression Inventory (18), and Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (19). These instruments have demonstrated satisfactory reliability or validity in previous studies of Chinese populations.

The Short-Form Health Survey generated a norm-based physical component summary and mental component summary that encapsulated the eight dimensional scores of the instrument with a population mean of 50 (SD=10) (15, 16). The SCL-90 produced a global severity index that was the mean score of its 90 items (17).

Outcome Assessment

We assessed two types of outcome. For general outcome, a composite score (average outcome score) of the Morgan-Russell Outcome Assessment Schedule was derived from nutritional status, menstrual function, mental status, sexual adjustment, and socioeconomic status (9). A higher score indicated better recovery (range=0–12). On the basis of the average outcome score, the subjects were placed into three outcome category groups (20): poor (score=0–4), intermediate (score >4 and ≤8), and good (score >8). We also assessed eating disorder diagnosis outcome, which included four DSM-III-R categories: 1) no eating disorder; 2) anorexia nervosa, typical or atypical (body mass index ≤16.49 kg/m2 and absence of menstruation); 3) bulimia nervosa (recovered anorexia nervosa with more than two binges a week for 3 months or more); and 4) eating disorder not otherwise specified (less than two binges a week or habitually spitting out food after ingestion).

Statistical Analysis

Simple statistics, including chi-square tests, t tests, analyses of variance (ANOVAs), and Pearson correlation analyses, were used to compare differences in outcome. All p values were two-tailed. When the categorical data analysis involved >25% of cells with an expected count <5, Fisher’s exact test was used. Differences of continuous variables were analyzed by using ANOVA, with post hoc Bonferroni t test delineating group differences. To examine the predictive ability of independent risk factors, we used logistic regression and multiple regression for categorical outcome and continuous outcome variables, respectively. The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis yielded a median recovery time (i.e., the duration for half of the subjects to recover [21, 22]), and recovery over time was plotted.

Results

Two subjects committed suicide within a year of clinical presentation, and one died from emaciation (body mass index=9.2 kg/m2) 4.7 years after clinical presentation. The crude mortality rate was 3.4% (N=3 of 88). According to official death statistics (1976–1999) in Hong Kong, the expected age/gender specific mortality rate for our subjects, using the subjects-years method (3), was 0.285. Thus, the standardized mortality ratio was 10.5 to 1.

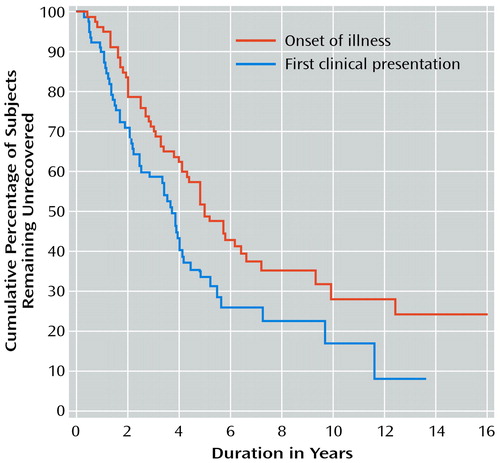

The mean age of the 80 subjects at the time of study was 26.9 years (SD=6.7, range=16.2–47.7). The mean current body mass index was 18.5 kg/m2 (SD=2.8, range=11.9–25.5). Most subjects had regular menstruation (67.5%, N=54), but 6.3% (N=5) and 26.3% (N=21) had irregular (once every 2 to 3 months) and no menstruation, respectively. The mean duration of illness was 2.2 years (SD=3.1, range=0.2–17.4). With respect to the first clinical presentation and onset of illness, the median duration for recovery (defined as body mass index ≥17.5 kg/m2 and three consecutive menstrual cycles) was 3.7 years (95% confidence interval [CI]=3.2–4.2) and 5.0 years (95% CI=3.9–6.1), respectively (Figure 1).

Many subjects continued to exhibit disordered eating behaviors, including exercise to lose weight (40.0%, N=32), binging (46.3%, N=37), vomiting (20.0%, N=16), abuse of laxatives (10.0%, N=8), and taking diet pills and diuretics (8.8%, N=7). Most of the subjects had never been married (80.0%, N=64), while 12.5% (N=10) and 7.5% (N=6) were either married or cohabiting, respectively. Fifty subjects (62.5%) were fully employed, and 21.3% (N=17) were students; the remaining subjects were either irregularly employed (8.8%, N=7) or unemployed (7.5%, N=6).

Semistructured Assessments

According to the average outcome scores of 76 subjects (four subjects did not complete the Morgan-Russell Outcome Assessment Schedule and SCID), 61.8% (N=47), 32.9% (N=25), and 5.3% (N=4) of the subjects were classified as having good, intermediate, and poor outcomes, respectively. Eating disorder diagnosis outcomes were as follows: no eating disorder, 45.0% (N=36); anorexia nervosa, 16.3% (N=13, with six subjects having the restrictive subtype and seven having the bulimic subtype); bulimia nervosa, 20.0% (N=16); and eating disorder not otherwise specified, 18.8% (N=15). A worse outcome category was associated with worse eating disorder diagnosis outcome (Fisher’s exact test=37.70, p<0.001). The mean average outcome score was 8.3 (SD=2.2, range=3.6–11.7). This score was significantly different among the three outcome category groups (F=112.42, df=2, 73, p<0.001) and the four eating disorder diagnosis outcome groups (F=19.57, df=3, 72, p<0.001).

Other axis I diagnoses seen in the 76 subjects who completed the SCID included current major depressive episode (N=15, 19.7%) and dysthymia (N=12, 15.8%). Sixty-two subjects (81.6%) experienced a depressive disorder in their lifetime. Those with current depressive disorder scored significantly higher than those with no current depressive disorder on the Hamilton depression scale (t=5.67, df=72, p<0.001) and Beck Depression Inventory (t=4.78, df=72, p<0.001). Current anxiety disorders were seen in 19.7% (N=15) of the subjects, including obsessive-compulsive disorder (N=4), panic disorder (N=4), agoraphobia without panic (N=0), social phobia (N=4), simple phobia (N=0), and generalized anxiety disorder (N=8). Lifetime anxiety disorders were reported in 27.6% (N=21) of the subjects, including obsessive-compulsive disorder (N=8), panic disorder (N=7), agoraphobia without panic (N=1), social phobia (N=4), and simple phobia (N=3). Those with current anxiety disorders scored significantly higher on the SCL-90 than those with no current anxiety disorder (t=4.48, df=72, p<0.001).

Self-Rated Assessments

Eating disordered behavior

The three outcome category groups demonstrated significant differences in scores on the Eating Attitudes Test-26, the questionnaire version of the Eating Disorder Examination, and all Eating Disorder Inventory-1 subscales except for the maturity fears subscale (F=3.28–16.12, df=2, 71, p value range=0.001 to 0.05). Post hoc comparisons revealed that eating disordered behavior increased significantly from good to poor outcome groups. When subjects were compared on the basis of their eating disorder diagnosis outcome, the four groups showed significant differences in scores on the Eating Attitudes Test-26, the questionnaire version of the Eating Disorder Examination, and four Eating Disorder Inventory-1 subscales (Table 2). Post hoc comparisons indicated that the subjects with no eating disorder exhibited significantly less eating disordered behavior than the anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa groups.

General psychopathology

Significant group differences in scores on the Hamilton depression scale, Beck Depression Inventory, SCL-90, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, and both the physical component summary and mental component summary of the Short-Form Health Survey were found among those classified as having good, intermediate, and poor outcome (F=9.11–27.72, df=2, 71, p value range=0.001–0.05). Post hoc tests showed that the good outcome group had the least general psychopathology, best physical and mental functioning, and highest self-esteem. When subjects were compared on the basis of their eating disorder diagnosis outcome, significant group differences were found for scores on the Beck Depression Inventory, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, and the mental component summary of the Short-Form Health Survey (Table 2). Post hoc tests showed that the subjects with no eating disorder had significantly higher self-esteem than the bulimia nervosa group.

Relationships between clinical variables and outcome

Average outcome scores were negatively correlated with scores on the Eating Attitudes Test-26, the questionnaire version of the Eating Disorder Examination, all Eating Disorder Inventory-1 subscales (except for maturity fears), Hamilton depression scale, Beck Depression Inventory, and SCL-90 (r=–0.34 to –0.67, p value range=0.001–0.003). Average outcome scores were positively correlated with scores on the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale and both the physical component summary and mental component summary of the Short-Form Health Survey (r=0.51 to 0.64, p<0.001). Average outcome score was inversely correlated with duration of illness (r=–0.24, p<0.04) and age of presentation (r=–0.30, p=0.009). Subjects with religious affiliations had a lower average outcome score than those without (t=2.16, df=74, p<0.04).

Typical Versus Atypical Anorexia Nervosa

As seen in Table 3, typicality (i.e., the presence of fat phobia) was significantly associated with poorer outcome. Typicality was marginally associated with poor outcome according to the eating disorder diagnosis outcome. Specifically, more typical than atypical subjects continued to fulfill criteria for anorexia nervosa (18.64% versus 9.52%) or developed bulimia nervosa (25.42% versus 4.76%). Of those subjects with typical anorexia nervosa, 36.4% and 63.6% were restrictive and bulimic, respectively, whereas all subjects with atypical anorexia nervosa were restrictive (Table 3).

Premorbid body mass index and body mass index at presentation were significantly higher in typical anorexia nervosa subjects than in atypical subjects (premorbid: mean=20.1 kg/m2 [SD=2.3] versus 18.5 kg/m2 [SD=2.2], respectively [t=2.97, df=86, p=0.004]; at presentation: mean=14.8 kg/m2 [SD=1.9] versus 13.2 kg/m2 [SD=1.6] [t=3.64, df=86, p<0.001]). The age at onset/presentation and duration of illness were not statistically different. Typical subjects scored higher on specific psychopathology (Table 3). There were no between-group differences in average outcome score, general psychopathology, and current/lifetime rates of depressive/anxiety disorders.

Prediction of Outcome

Putting the clinical and sociodemographic variables into regression equations to predict outcome by eating disorder diagnosis outcome (no eating disorder plus eating disorder not otherwise specified=1, anorexia nervosa plus bulimia nervosa=0) yielded typicality of anorexia nervosa (odds ratio=0.21, 95% CI=0.056–0.80; p<0.03) and age at onset (odds ratio=0.87, 95% CI=0.76–0.98; p<0.03). This indicated that typicality of anorexia nervosa and older age at onset predicted poor outcome (namely, unrecovered anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa). When outcome categories were used (good=1, intermediate plus poor=0), typicality (odds ratio=0.13, 95% CI=0.028–0.62; p=0.01) and age at onset (odds ratio=0.88, 95% CI=0.77–0.99; p<0.05) also predicted poor outcome. Duration of illness contributed significantly to the prediction of lower average outcome score (beta=–0.16, p<0.05). Neither premorbid body mass index nor body mass index at presentation predicted eating disorder diagnosis outcome or outcome category.

Discussion

This study has limitations. First, since our subjects received treatment from a university-affiliated unit, the generalizability of the findings to other treatment settings is limited. Second, the tracking rate was suboptimal (N=80 of 85, 94.1%). Third, the small number of atypical subjects could have precluded more significant differences in outcome from typical subjects from being found.

The overall outcome profile of our subjects (i.e., mortality, average outcome score, eating disorder diagnosis outcome, specific and general psychopathology, and axis I morbidity) was strikingly similar to those reported in Western studies (2–5, 9, 20). Although anorexia nervosa has been described as a Western culture-bound disorder, these findings suggest that the general outcome of the illness is stable across cultures. This lends substantial support to its disease validity.

Kleinman has cautioned that there is a propensity for researchers of psychopathology to inflate what is universal by sampling prototypical subjects and thereby to lose sight of what is culturally salient (1). By including atypical subjects, this study indicated that typical and atypical anorexia nervosa exhibited differences in outcome that are of empirical interest. Although their general psychopathology and axis I morbidity were similar, patients with typical anorexia nervosa were more likely to develop bulimia nervosa or the bulimic subtype of anorexia nervosa. Additionally, the presence of fat phobia was an independent risk factor for poor outcome in terms of developing anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa.

Historical studies have suggested that the anorexic illness is much less frequently associated with bulimia, which led researchers to conclude that bulimia nervosa as we conceptualize it today is a recent disorder (7). From this perspective, it would appear that the cultural fear of fatness not only shapes the content (typical versus atypical) of anorexia nervosa but also lengthens its course through the development of bulimia. This appears consistent with a U.S. study that atypical anorexia nervosa exhibited a more benign outcome and less bulimia than typical anorexia nervosa (22). The two groups of anorexia nervosa subjects in this study continued to exhibit distinct phenomenology 9 years after the onset of illness, suggesting that atypical anorexia nervosa may be a nosologically valid entity.

If we take the liberty to assume that atypical anorexia nervosa was ontologically related to ancient forms of the anorexic illness that did not demonstrate fat phobia (1), this might arguably be the first non-Western study to provide empirical evidence on the intermediate-term course of modern versus plausibly “ancient” forms of the illness. It raises the intriguing possibility that modern typical anorexia nervosa may run a more malignant course than historical forms of the “same” illness in which afflicted subjects refused food for reasons other than fat phobia. While the salience of atypicality in different cultural contexts requires further studies (1), we may speculate why atypical anorexia nervosa might exhibit a better eating disorder outcome than typical anorexia nervosa. Consistent with previous studies (1), subjects with atypical anorexia nervosa were premorbidly slimmer and thus under less pressure to diet than subjects with typical anorexia nervosa. Their illness was usually triggered by psychosocial stressors other than the fear of fatness, which was thus not a perpetuating factor. In contrast, as typical anorexia nervosa patients regained weight, the recalcitrant fear of fatness and the attendant weight control behavior would pose resistance to recovery as well as promote bulimia—itself a risk factor for poor outcome (3, 4)—as a pathological means of weight control. This would suggest that public health interventions that counteract the cultural fear of fatness may improve the outcome of anorexia nervosa.

Some researchers believe that intensive treatment improves the outcome of anorexia nervosa (23). The outcome of our subjects was similar to that of Western anorexia nervosa patients (2, 3) even though they did not receive formal psychotherapeutic interventions. After an hour of intake evaluation, the treatment they received consisted of monthly psychoeducational outpatient visits (roughly 10 minutes in duration) and a varying period of hospitalization with a dominant focus on weight gain under nursing supervision in an acute psychiatric ward. The similar outcome profile thus raised the controversial possibility of whether anorexia nervosa runs a “natural” course independent of treatment (5). However, we have not evaluated subjects’ perspective of recovery. It remains possible that a higher level of subject satisfaction and interpersonal functioning could result from intensive psychotherapy.

Of the baseline features studied in logistic regression, only early age at onset, besides atypicality of anorexia nervosa, predicted better eating disorder outcome. This is in keeping with Western studies (2). Survival analysis affirmed that beyond 6 years after the onset of illness, the chance for recovery might be slim (3). Unfortunately, our subjects did not seek professional help until 2.2 years after the onset of illness, reflecting an impaired access to care that might be due to low awareness, stigma, inadequate service, or poor recognition by practitioners. Since eating disorders in Asian societies have been inadequately managed in overcrowded psychiatric settings, and undertreatment is an escalating global problem under the new managed care culture, the importance of promoting early identification and sufficient intervention by experienced professionals can hardly be overemphasized (24).

|

|

|

Received Nov. 15, 2001; revision received Aug. 29, 2002; accepted Oct. 14, 2002. From the Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong; and the Department of Psychiatry, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston. Address reprint requests to Dr. Lee, Department of Psychiatry–11/F, Tai Po Hospital, Tai Po, Hong Kong; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a grant (CUHK4029/98M) from the Research Grant Council, Hong Kong. The authors thank Dr. Chris Fairburn and Dr. Cindy L.K. Lam for their permission to use, respectively, the Eating Disorder Examination and the Hong Kong Chinese normative data of the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey.

Figure 1. Time to Recovery From Onset of Illness and From First Clinical Presentation for 80 Chinese Women With Anorexia Nervosa

1. Lee S: Fat phobia in anorexia nervosa: whose obsession is it? in Eating Disorders and Cultures in Transition. Edited by Nasser M, Katzman M, Gordon R. London, Routledge, 2001, pp 40-54Google Scholar

2. Eckert ED, Halmi KA, Marchi P, Grove W, Crosby R: Ten-year follow-up of anorexia nervosa: clinical courses and outcome. Psychol Med 1995; 25:143-156Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Hsu LKG: Eating Disorders. New York, Guilford, 1990Google Scholar

4. Zipfel S, Lowe B, Reas DL, Deter HC, Herzog W: Long-term prognosis in anorexia nervosa: lessons from a 21-year follow-up study. Lancet 2000; 355:721-722Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Steinhausen H-C: The outcome of anorexia nervosa in the 20th century. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1284-1293Link, Google Scholar

6. Sullivan PF: Mortality in anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1073-1074Link, Google Scholar

7. Russell GFM, Treasure J: The modern history of anorexia nervosa: an interpretation of why the illness has changed. Ann NY Acad Sci 1989; 575:13-27Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Great Britain Office of Population Census and Surveys: Standard Occupation Classification. London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1990Google Scholar

9. Morgan HG, Russell FM: Value of family background and clinical features as predictors of long-term outcome in anorexia nervosa: four-year follow-up study of 41 patients. Psychol Med 1975; 5:355-371Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Zheng YP, Zhao JP, Phillips M, Liu JB, Cai MF, Sun SQ, Huang MF: Validity and reliability of the Chinese Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 152:660-664Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: User’s Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

12. Lee S, Lee AM, Leung T, Yu H: Psychometric properties of the Eating Disorders Inventory (EDI-1) in a nonclinical Chinese population in Hong Kong. Int J Eat Disord 1997; 21:187-194Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Lee AM, Lee S: Disordered eating and its psychological correlates among Chinese adolescent females in Hong Kong. Int J Eat Disord 1996; 20:177-183Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z: The Eating Disorder Examination, 12th ed, in Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment and Treatment. Edited by Fairburn CG, Wilson GT. New York, Guilford, 1993, pp 317-360Google Scholar

15. Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B: SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, New England Medical Center, Health Institute, 1993Google Scholar

16. Lam LKC, Gandek B, Ren XS, Chan MS: Test of scaling assumptions and construct validity of the SF-36 Health Survey. J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51:1139-1147Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Derogatis LR: How to Use the Symptom Distress Checklist (SCL-90) in Clinical Evaluation: Psychiatric Rating Scale, vol III: Self-Report Rating Scale. Nutley, NJ, Hoffmann-La Roche, 1975Google Scholar

18. Zheng Y, Liang W, Gao L, Zhang G, Wong C: Applicability of the Chinese Beck Depression Inventory. Compr Psychiatry 1988; 29:484-489Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Wang XD (ed): Rating Scales for Mental Health. Beijing, Chinese Mental Health Association, 1993Google Scholar

20. North C, Gowers S, Byram V: Family functioning and life events in the outcome of adolescent anorexia nervosa. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 171:545-549Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Strober M, Freeman R, Morrell W: The long-term course of severe anorexia nervosa in adolescents: survival analysis of recovery, relapse, and outcome predictors over 10-15 years in a prospective study. Int J Eat Disord 1997; 22:339-360Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Strober M, Freeman R, Morrell W: Atypical anorexia nervosa: separation from typical cases in course and outcome in a long-term prospective study. Int J Eat Disord 1999; 25:135-142Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Crisp AH, Callender JS, Halek C, Hsu LKG: Long-term mortality in anorexia nervosa: a 20-year follow-up of the St George’s and Aberdeen cohorts. Br J Psychiatry 1992; 161:104-107Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Sullivan PF, Bulik CM, Fear JL, Pickering A: Outcome of anorexia nervosa: a case-control study. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:939-946Link, Google Scholar