Capsulotomy for Refractory Anxiety Disorders: Long-Term Follow-Up of 26 Patients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The objective of the present study was to evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of capsulotomy in patients with anxiety disorders. METHOD: Twenty-six patients who had undergone bilateral thermocapsulotomy were followed up 1 year after the procedure and after a mean of 13 years. Primary diagnoses were generalized anxiety disorder (N=13), panic disorder (N=8), and social phobia (N=5). Measures of psychiatric status included symptom rating scales and neuropsychological testing. Ratings were done by psychiatrists not involved in patient selection or postoperative treatment. A quantitative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluation was conducted to search for common anatomic denominators. Seventeen of the 23 patients who were alive at long-term follow-up were followed up in person, and one was interviewed by telephone; the relatives of these 18 patients were interviewed. RESULTS: The reduction in anxiety ratings was significant both at 1-year and long-term follow-up. Seven patients, however, were rated as having substantial adverse symptoms; the most prominent adverse symptoms were apathy and dysexecutive behavior. Neuropsychological performance was significantly worse in the patients with adverse symptoms. No common anatomic denominator could be found in responders in the analysis of MRI scans. CONCLUSIONS: Thermocapsulotomy is an effective treatment for selected cases of nonobsessive anxiety but may carry a significant risk of adverse symptoms indicating impairment of frontal lobe functioning. These findings underscore the importance of face-to-face assessments of adverse symptoms.

Some cases of severe anxiety disorders may benefit from neurosurgery for mental disorders (1–3). Current neurosurgery procedures for mental disorders include cingulotomy, subcaudate tractotomy, and capsulotomy. Capsulotomy, where bilateral lesions are produced in the anterior limb of the internal capsule, was first reported in 1949 by Talairach et al. (4). Leksell et al. (5) developed the method further and termed it “bilateral internal capsulotomy.”

The main indication for capsulotomy and cingulotomy is obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). The reported efficacy for this disorder in most studies is satisfactory, ranging from 40% of patients with permanent improvement (6) to 73% at least “much improved” (7). All studies of neurosurgery for mental disorders have been uncontrolled in that placebo or sham operations have not been applied. A review of capsulotomy studies is presented in Table 1.

The reported rate of adverse symptoms arising from capsulotomy varies considerably. Herner (6) noted that frontal lobe deficit syndrome was obvious at follow-up in 30% of 116 capsulotomy cases. Among subjects given capsulotomy for anxiety, 40% had adverse symptoms of mild severity and 13% had adverse symptoms of moderate severity. Adverse symptoms in Herner’s study and in a study by Kullberg (9) included fatigue, emotional blunting, emotional incontinence, indifference, low initiative, disinhibition, and impaired sense of judgment. A few studies have compared different neurosurgical methods: Kullberg (9) noted that cingulotomy produced fewer adverse symptoms (transient confusion and affective deficit) in the immediate postoperative phase than capsulotomy. In another study (10), conventional thermocapsulotomy was compared with gamma-radiation capsulotomy in OCD patients. The efficacy was satisfactory in both groups, but in the gamma-radiation capsulotomy group there were no signs of postoperative confusion and disorientation, common temporary adverse symptoms after thermocapsulotomy. Postoperative seizures have been reported in 3% of patients by Herner (6) and in 4% by Mindus (14).

Nyman and Mindus (11) found that the general neuropsychological performance of patients whose performance on neuropsychological tests was within normal ranges before capsulotomy remained remarkably intact 1 year after capsulotomy. However, perseverative responses on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test were significantly more common after capsulotomy in some patients, possibly indicating a dysfunction of systems involving the frontal lobes.

The aim of the present study was to assess the efficacy (after 1 year and long-term) and safety of capsulotomy in 26 consecutive patients with nonobsessional anxiety disorders by applying clinical symptom ratings and cognitive tests.

Method

Patients

All 26 consecutive patients with anxiety disorders other than OCD who were treated with bilateral thermocapsulotomy between 1975 and 1991 at the Karolinska Hospital in Stockholm were included in the study. Fifteen of the patients were women, and 11 were men.

The patients’ mean age at first capsulotomy was 41.4 years (SD=6.5, range=31–54), and their mean duration of illness at the time of surgery was 18.0 years (SD=9.2, range=5–40). Their mean age at long-term follow-up was 54.5 years (SD=8.3, range=42–71, N=18).

For patients operated on after 1980, the DSM-III or DSM-III-R criteria for anxiety disorders were systematically assessed on the basis of a clinical semistructured interview. At long-term follow-up, the preoperative diagnoses were checked by P.M. and C.R. The patients’ primary diagnoses were generalized anxiety disorder (N=13), panic disorder (N=8), and social phobia (N=5). Table 2 shows other current and lifetime comorbid psychiatric disorders at the time of surgery. None of the patients had OCD as their primary diagnosis, although six had OCD of minor severity as a comorbid condition.

Inclusion criteria for capsulotomy have been described elsewhere (15, 16). In sum, they were 1) illness was chronic (duration ≥5 years), 2) illness caused substantial suffering and considerable reduction in psychosocial functioning, 3) current psychological and pharmacological treatment options were tried systematically for at least 5 years without substantial effect, and 4) the patient provided informed consent.

All patients had participated in psychotherapeutic trials to little or no avail. Nine patients had been treated with individual behavioral therapy, and the remaining patients had received different long-term psychodynamic psychotherapies.

All patients had been treated with benzodiazepines and antidepressants. Eighteen patients had been treated with serotonin reuptake inhibitors (clomipramine, zimelidine, or citalopram), seven had been treated with monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and 16 had been treated with neuroleptics. Thirteen had received ECT.

Eighteen of the 26 patients were available for long-term follow-up; 17 were followed up in person, and one was interviewed by telephone because the illness of a relative prevented her from coming to the interview. Of the eight patients lost to long-term follow-up, three had died (of suicide, chronic alcoholism, and cardiovascular disease, respectively), two were too somatically ill to be interviewed, one refused to participate, and two did not show up. The patient who committed suicide (patient 12) made multiple suicide attempts before the first surgery and had long been suicidal. Relatives of all 18 patients were interviewed.

The ethics committee at the Karolinska Hospital approved the study. After a complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. Fourteen of the patients were previously included in a 1-year follow-up study of capsulotomy (14), and five patients were included in an earlier neuropsychological study (11).

Surgical Technique

All patients were given stereotactic, bilateral thermocapsulotomy (performed by B.A.M.). The target was located about halfway along the line connecting the anterior commissure and the tip of the frontal horn, i.e., 19–21 mm anterior to the anterior commissure. Surgery was performed under local anesthesia with moderate sedation. Lesions were produced with monopolar (nine operations) or bipolar (21 operations) electrodes. For bipolar lesions the interelectrode distance was 6 mm. The height of the lesions was 18–20 mm, and for bipolar lesions the mediolateral extension was approximately 8 mm. Three patients were operated on a second time due to lack of improvement; one of these patients (patient 10) was operated on a third time.

Follow-Up Assessments

Short-term (1 year after first surgery) and long-term (mean=13 years after first surgery, SD=4.1, range=7–23) assessments were compared with preoperative data. The clinical ratings at the long-term follow-up were done by C.R. or S.A., who were not involved in patient selection or postoperative care. The long-term follow-up was conducted in 1998 and 1999. The preoperative and 1-year ratings were done by P.M.

The Brief Scale for Anxiety (17) is a rating scale for measuring anxiety symptoms, derived from the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale (18). The Brief Scale for Anxiety consists of eight reported and two observed items, scored on a 0–6 Likert scale. In the present study, only the eight reported items were used.

The Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (19) is a widely used depression rating scale. Global improvement was measured by the investigator on the Physician’s Global Improvement Scale and by the patient on the Patient’s Global Improvement Scale (20). In the present study an 11-point Likert scale was used on which a score of 10 indicates maximal improvement. The Global Assessment of Functioning Scale, i.e., axis V of DSM-IV (p. 32), is a composite measure of current psychological, social, and occupational functioning. The Physician’s Global Improvement Scale, Patient’s Global Improvement Scale, and Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scales were used only at long-term follow-up.

All adverse symptoms were recorded during a semistructured clinical interview at long-term follow-up. Because we were unaware of rating instruments for symptoms of frontal lobe functioning, we constructed a simple rating scale, the Execution, Apathy, Disinhibition Scale, designed to measure three important functions of what has been postulated to be frontal lobe dysfunction, namely, executive dysfunction, apathy, and disinhibition (21). Severity is rated on a 4-point Likert scale (scores=0–3) for each of the three items. A score of 3 indicates the highest level of severity. Patients with a total score ≥3 were rated as having significant dysfunction. All patients were rated by two psychiatrists (C.R. and S.A.) on the basis of videotaped clinical interviews with each patient and his or her relatives and/or other available material (e.g., patient files). The interrater reliability for the total Execution, Apathy, Disinhibition Scale scores was 0.92 (p<0.001). Disagreement occurred regarding only one patient. For the separate ratings, the interrater reliability varied between 0.72 (disinhibition, p<0.001) and 1.00 (apathy, p<0.001). There were no significant differences between the two raters. Consensus was reached for all ratings before the Execution, Apathy, Disinhibition Scale scores were entered into the raw data matrix.

The Karolinska Scales of Personality (22) were administered preoperatively and postoperatively. Results for this measure will be presented elsewhere. A battery of neuropsychological tests was applied at long-term follow-up. These tests assess premorbid cognitive function, executive functions, and short-term working memory (Table 3).

The stereotactic CT scan that preceded the surgical procedure and served to define the coordinates for the intended lesions in the internal capsule also served as baseline examination. CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were obtained to confirm lesion placement in all but two patients (patients 20 and 21). At the time of long-term follow-up, 12 patients were available for a second imaging study with MRI (1.5-T GE Signa scanner [GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee]) that included standard imaging sequences (T1, proton density, and T2 weightings). The mean postoperative MRI follow-up duration was 13.8 years (SD=4.4, range=8–23). One of the 12 follow-up MRI data sets was lost. A well-demarcated hyperintense signal change within the anterior limb of the internal capsule on proton-weighted sequences was defined as the lesion. Lesion size and site were quantified on three anatomic levels according to the method described by Lippitz et al. (13).

Statistical Analyses

All variables were summarized with standard descriptive statistics (frequency, mean, standard deviation, and median). For approximately normal distributions, statistical analyses of continuous variables were performed with parametric statistics (independent and dependent Student’s t test and analysis of variance for repeated measurements). Because of skewed distributions, interrater reliability for the Execution, Apathy, Disinhibition Scale ratings were calculated by the Kendall rank correlation method. If nonnormality and/or outliers were observed, nonparametric methods (Mann-Whitney test and Wilcoxon rank sum test) were applied. For discrete variables, the chi-square method and Fisher’s exact test were used.

Results

Efficacy Variables

Preoperative and postoperative data for the individual patients are presented in Table 4. For the whole group of 26 patients, the mean preoperative Brief Scale for Anxiety score was 22.0 (SD=5.6, range=12–31); for 25 patients 1 year after the operation the mean score was 4.6 (SD=4.2, range=0–18), and for 18 patients at long-term follow-up it was 9.9 (SD=5.8, range=1–23). The changes were significant both at 1 year (Z=4.38, p<0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test) and at long-term follow-up (Z=3.58, p<0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test) compared to preoperative ratings. When the last observations (the baseline or 1-year data) for the eight subjects not seen at long-term follow-up were carried forward (last observation carried forward), the results were still significant.

There were no significant between-diagnoses differences. Using a definition of a ≥50% reduction in Brief Scale for Anxiety score, we rated 23 (92%) of 25 patients as responders at the 1-year follow-up (Table 4). At long-term follow-up the responder rate was 67% (12 of 18 patients) (Table 4). With a 9–10 score (markedly improved, major improvement, or back to normal) on the Patient’s Global Improvement Scale and Physician’s Global Improvement Scale as additional criteria to the ≥50% reduction in Brief Scale for Anxiety score to indicate remission, the remission rate at long-term follow-up was 56% (10 of 18 patients) for the Patient’s Global Improvement Scale and 33% (six of 18 patients) for the Physician’s Global Improvement Scale.

The mean preoperative Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale score was 17.6 (SD=7.6, range=5–36), indicating mild to moderate depression (28). One year after the operation the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale score had decreased to 6.8 (SD=7.0, range=0–26), and at long-term follow-up it was 8.0 (SD=6.8, range=0–24). The changes from preoperative scores were significant (Z=4.29, p<0.001, and Z=3.14, p<0.01, respectively, Wilcoxon rank sum test). The mean ratings of global improvement at long-term follow-up were 7.2 (SD=3.9, range=0–10) for the Patient’s Global Improvement Scale and 7.0 (SD=2.8, range=2–10) for the Physician’s Global Improvement Scale, indicating that on average the patients were moderately improved. The mean current Global Assessment of Functioning Scale at long-term follow-up was 53 (SD=14, range=30–75), indicating moderate symptom severity and/or functional disability. There were no significant differences between the diagnoses in the results for the secondary efficacy variables.

Adverse Symptoms

Seven patients had attempted suicide after the operation, and 11 had made attempts before the baseline assessment. Long-term postoperative scores on the Execution, Apathy, Disinhibition Scale are displayed in Table 4. Nine patients scored ≥1 on the execution variable, seven scored ≥1 on the apathy variable, and seven scored ≥1 on the disinhibition variable. Examples of poor execution were poor planning and problem-solving abilities, including inability to perform simple household tasks, such as taking out the garbage, and showing poor judgment, resulting in several economically disastrous car deals. Examples of apathy included neglect of hygiene and clothing, lack of initiative, passivity, and fatigue. Disinhibition included behavior such as foul language and indecent exposure, unmotivated laughter, undue familiarity, being outspoken in an insulting way, and poor control of aggression.

Five of the 18 patients examined at long-term follow-up had a total Execution, Apathy, Disinhibition Scale score ≥3 and were consequently rated as having substantial clinical symptoms indicating frontal lobe dysfunction. The eight patients who could not be examined at long-term follow-up were rated on the basis of all available material, including medical records. Two of these patients (patients 1 and 19) had Execution, Apathy, Disinhibition Scale scores ≥3. The seven patients with Execution, Apathy, Disinhibition Scale scores ≥3 were compared with the 19 whose scores were <3.

The patients with Execution, Apathy, Disinhibition Scale scores ≥3 had significantly lower scores on the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale than those whose scores were <3 (t=3.01, df=16, p<0.01, unpaired t test). The Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale scores at long-term follow-up were nonsignificantly higher (Mann Whitney U=18, p=0.15) for the patients with Execution, Apathy, Disinhibition Scale scores ≥3. The Patient’s Global Improvement Scale and Physician’s Global Improvement Scale scores indicated greater improvement in the patients with scores <3 (Patient’s Global Improvement Scale: Mann Whitney U=17, p=0.15, and Physician’s Global Improvement Scale: Mann Whitney U=4.5, p<0.01). It is noteworthy that of the three patients who had renewed surgery, two had Execution, Apathy, Disinhibition Scale scores ≥3. There was no relationship between Execution, Apathy, Disinhibition Scale score and the type of electrodes used (monopolar or bipolar).

Case Reports

To illustrate our findings, two short case vignettes are presented.

Case 1

Mr. N (patient 6), age 66, who had a history of unspecified “adjustment problems” during childhood and adolescence, first experienced debilitating anxiety attacks at age 30 that seemed to be triggered by traumatic life events, including the death of his wife. He remarried shortly after. His somatic history included a concussion and suspected encephalitis. Medication and psychotherapy provided minor relief, and the patient periodically consumed alcohol daily for anxiety relief. Capsulotomy was performed at age 48. Directly after the operation and at follow-up his anxiety was markedly decreased and he was enthusiastic about having undergone surgery. A substantial element of tension remained, however, and his alcohol consumption gradually increased. Fatigue and passivity were observed both by his family and the attending physician, and they seemed to progress over the years.

At long-term follow-up the patient clearly lacked drive and initiative. He usually sat in a chair all day and read the same book (about cats) he has been reading for years, neglected his personal hygiene, and was content, oblivious to the fact that his wife was deeply troubled by the situation.

Case 2

Ms A (patient 23) described herself as having been an insecure and shy child. At age 27 her insecurity around people began to increase and she developed severe avoidance of all social situations, including the use of public transportation. Treatments included insight-oriented psychotherapy, clomipramine, benzodiazepines, behavioral therapy, and neuroleptics. By age 34 she was unable to continue her job as a nurse’s assistant and was given a disability pension. Feeling increasingly desperate, she took the initiative to be evaluated for capsulotomy, which was performed at age 40. At the 2-month follow-up most of her avoidance behavior had dissipated and she needed no medication. Within a year she was back at her old job and reported that her social anxiety “was a closed chapter.”

At long-term follow-up, at age 52, she reported leading a life without limitations and stated, “Without the operation I wouldn’t be alive today.”

Other case reports can be obtained on request.

Seizures and Weight Changes

Two cases of postoperative seizures were recorded. In one, seizures occurred three times in the first postoperative year and were subsequently effectively treated with carbamazepine. In the other case, the seizures led to vertebral compression fractures.

Weight change was evaluated in nine women and four men. The patients’ mean weight preoperatively was 74.8 kg (SD=20.9, range=39–120), at 1 year it was 84.2 kg (SD=19.3, range=65–143), and at long-term follow-up it was 86.2 kg (SD=22.2, range=55–130). The weight change was more pronounced in the women, with a mean increase of 15.1 kg (SD=15.7, range=–10–39) at the 1-year follow-up, whereas there was no weight gain in the men (mean=–1.2 kg, SD=6.3, range=–9 to 6).

Neuropsychology

The patients had a low educational level (mean=9.5 years, SD=2.3, range=7–14). There was no difference in this regard between the patients with Execution, Apathy, Disinhibition Scale scores ≥3 and those with scores <3.

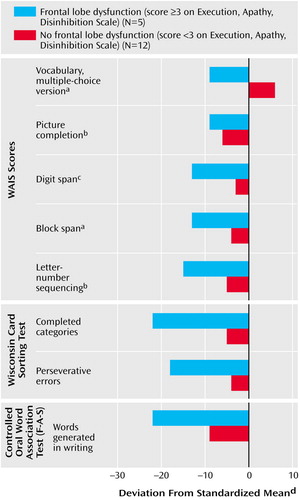

The results of the neuropsychological tests are shown in Table 5 and Figure 1. The patients performed at an average level in the vocabulary test, indicating a normal premorbid functional level. The mean level of executive function was below average, as was that for short-term and working memory.

The patients with Execution, Apathy, Disinhibition Scale scores ≥3 performed worse on all tests than those whose scores were <3. For the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test and measures of short-term and working memory, the patients with Execution, Apathy, Disinhibition Scale scores ≥3 had statistically significantly lower scores than patients whose Execution, Apathy, Disinhibition Scale scores were <3.

Radiology and Quantitative MRI Analysis

The baseline CT scans were unremarkable in all cases. At long-term follow-up with MRI one of 12 patients had signs of generalized brain atrophy, multiple white matter hyperintensities indicating small vessel disease, and residual signs of a frontal infarction. The infarction occurred postoperatively. In the other cases there were no obvious signs of brain pathology except for those induced by the surgery. The lesions appeared as areas of well-demarcated signal change. All lesions proved to be located in the anterior limb of the capsule, one completely contained within the capsule but the others to some minor degree also involving adjacent basal ganglia structure.

There was no common anatomic denominator found on the MRI scans of the eight patients who fulfilled the criteria for response at the long-term follow-up and had follow-up MRI scans. No correspondence between either the area or the site of the lesion and adverse symptoms (as defined by the Execution, Apathy, Disinhibition Scale ratings) was found. More detailed data can be obtained on request and will be presented elsewhere.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a study using up-to-date methods to evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of capsulotomy in patients with nonobsessional anxiety disorders. Ratings were done by two investigators who were not involved in patient selection and treatment, contrary to most previous studies of neurosurgery for mental disorders (12, 13, 29, 30). Of the 23 patients alive at long-term follow-up, 74% were followed up face-to-face, which is a high percentage compared with other studies (29, 31). Moreover, relatives of all patients evaluated at the long-term follow-up were interviewed.

Summary of Findings

The response rate with regard to anxiety symptoms was satisfactory: 67% of the patients were classified as responders at the long-term follow-up. The results for target symptoms in terms of efficacy are well in line with previous data for capsulotomy for OCD and for conditions other than OCD (6, 10, 13). The remission rate was considerably lower than the response rate, possibly reflecting the fact that the reduction in anxiety was not matched by an improvement in functioning according to Global Assessment of Functioning Scale ratings. For example, a substantial number of patients attempted suicide after the operation.

An unexpected finding was that seven of the 26 patients were rated as impaired with regard to clinical frontal lobe functioning. The types of adverse symptoms are similar to those reported previously (6, 9), with executive problems and apathy as the most prominent symptoms. The patients who did not complete the long-term follow-up were also rated on the Execution, Apathy, Disinhibition Scale, since dropouts could be due to adverse symptoms that would be missed if these patients had not been assessed.

Assessment of behavioral changes (Execution, Apathy, Disinhibition Scale) correlated with several of the neuropsychological tests, particularly those assessing executive and working memory functions. It is tempting to interpret this finding as indicating that the executive problems are consequences of the surgical procedure. However, this might not be the case, since patients with OCD who were undergoing capsulotomy were also shown to perform in the impaired range in tests of executive functions before the capsulotomy (32). Even though the patients in this study did not suffer from OCD as their primary diagnosis, they may nevertheless have had executive dysfunctions before the operation. It is possible that the observed association between behavior changes and neuropsychological test performance reflects greater vulnerability to adverse symptoms attributable to an already limited frontal lobe capacity. This also points to the possibility of individual differences in cognitive vulnerability, the details of which are still unknown. We suggest that all patients undergoing capsulotomy should be extensively examined before the operation in order to identify possible predictors of vulnerability. Since neuropsychological testing does not measure the clinical impact of frontal lobe dysfunction, the results of the present study underscore the importance of a clinical evaluation of frontal lobe functioning.

The level of weight increase seen primarily in female patients is in line with previous reports (6, 7, 14). The quantitative MRI analysis available for 11 patients at the long-term follow-up was not able to reproduce earlier findings (13) in OCD patients of a common anatomic denominator on the right side in responders. The patients in the present study had other diagnoses, but the surgical interventions were identical and were carried out during the same period of time.

Limitations

In most cases no preoperative neuropsychological data were available and ratings or measurements of frontal lobe functioning had not been performed preoperatively. Our results must therefore be interpreted with caution. An advantage of this study is that pre- and postoperative medical records were carefully studied and relatives were interviewed.

Like all other studies of neurosurgery for mental disorders, the present investigation lacked a placebo treatment. It has not been possible to establish a control treatment for conventional neurosurgery for mental disorders, and efforts to do this in gamma-radiation surgery have been hampered by technical problems.

The reported results concern patients with anxiety disorders other than OCD, the main indication for neurosurgery for mental disorders today. The extent to which the findings in the present study are valid for OCD cases is unknown, even if the target area in the brain is the same. The validity of these results for gamma-radiation capsulotomy is also unknown.

To some extent our data contradict other reports (12, 14, 33) indicating that the risk of adverse symptoms is small. One possible explanation might be that few of the earlier studies used systematic examinations of symptoms attributable to frontal lobe dysfunction, and some studies of neurosurgery for mental disorders might therefore have underestimated the risks.

The small number of patients with each diagnosis and in the whole group is another limitation, resulting in a low power and a risk of missing small and medium-sized effects (type II error).

Another important issue is how to evaluate the reported outcome. Some patients were satisfied with the results but were unaware of adverse symptoms that were obvious to their relatives. This alludes to the primary question posed by the present study: What price capsulotomy?

|

|

|

|

|

Received March 15, 2002; revision received Aug. 19, 2002; accepted Sept. 24, 2002. From the Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Sections for Psychiatry, Neurosurgery, and Neuroradiology, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm; and the Department of Psychiatry, Danderyd’s Hospital, Danderyd, Sweden. Address reprint requests to Dr. Rück, Psykiatri Centrum Karolinska, SE-171 76 Stockholm, Sweden; [email protected] (e-mail). Dr. Mindus died on Dec. 2, 1998.Supported by grant 01-7153/98 from the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare and grant 5454 from the Swedish Research Council.

Figure 1. Performance on Neuropsychological Tests at Long-Term Follow-Up of 17 Patients Given Capsulotomy Who Had Low (<3) or High (≥3) Scores on the Execution, Apathy, Disinhibition Scale

aWAIS-R as a Neuropsychological Instrument (23).

bWAIS-III (24).

cWAIS-R (27).

dMean=50, SD=10.

1. Ovsiew F, Frim DM: Neurosurgery for psychiatric disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997; 63:701-705Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Binder DK, Iskandar BJ: Modern neurosurgery for psychiatric disorders. Neurosurgery 2000; 47:9-21; discussion, 47:21-23Medline, Google Scholar

3. Jenike MA: Neurosurgical treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1998; 35:79-90Medline, Google Scholar

4. Talairach J, Hecaen H, David M: Lobotomie préfrontal limitée par électrocoagulation des fibres thalamo-frontales a leur émergence du bras anterieur de la capsule interne, in Proceedings, IV Congres Neurologique International. Paris, Masson, 1949, p 141Google Scholar

5. Leksell L, Herner T, Lidén K: Stereotaxic radiosurgery of the brain. Kungliga Fysiografiska Sällskapet i Lund Förhandlingar 1955; 25:1-10Google Scholar

6. Herner T: Treatment of Mental Disorders With Frontal Stereotaxic Thermo-Lesions: A Follow-Up Study of 116 Cases. Copenhagen, Munksgaard, 1961Google Scholar

7. Burzaco J: Stereotactic surgery in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive neurosis, in Biological Psychiatry. Edited by Perris C, Struwe G, Jansson B. Amsterdam, Elsevier/North-Holland, 1981, pp 1103-1109Google Scholar

8. Bingley T, Leksell L, Meyerson BA, Rylander G: Long term results of stereotactic capsulotomy in chronic obsessive-compulsive neurosis, in Neurosurgical Treatment in Psychiatry, Pain, and Epilepsy. Edited by Sweet WH, Obrador S, Martín-Rodriguez JG. Baltimore, University Park Press, 1977, pp 287-289Google Scholar

9. Kullberg G: Differences in effect of capsulotomy and cingulotomy. Ibid, pp 301-308Google Scholar

10. Rylander G: Stereotactic radiosurgery in anxiety and obsessive-compulsive states: psychiatric aspects, in Modern Concepts in Psychiatric Surgery. Edited by Hitchcock ER, Ballantine HTJ, Meyerson BA. Amsterdam, Elsevier/North Holland, 1979, pp 235-240Google Scholar

11. Nyman H, Mindus P: Neuropsychological correlates of intractable anxiety disorder before and after capsulotomy. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1995; 91:23-31Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Mindus P, Edman G, Andréewitch S: A prospective, long-term study of personality traits in patients with intractable obsessional illness treated by capsulotomy. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999; 99:40-50Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Lippitz BE, Mindus P, Meyerson BA, Kihlström L, Lindquist C: Lesion topography and outcome after thermocapsulotomy or gamma knife capsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: relevance of the right hemisphere. Neurosurgery 1999; 44:452-458; discussion, 44:458-460Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Mindus P: Capsulotomy in Anxiety Disorders—A Multidisciplinary Study (dissertation). Stockholm, Karolinska Institutet, 1991Google Scholar

15. Mindus P: Present-day indications for capsulotomy. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 1993; 58:29-33Medline, Google Scholar

16. Meyerson BA: Neurosurgical treatment of mental disorders: introduction and indications, in Textbook of Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery. Edited by Gildenberg PL, Tasker RR. New York, McGraw-Hill Health Professions Division, 1998, pp 1955-1963Google Scholar

17. Tyrer P, Owen RT, Cicchetti DV: The Brief Scale for Anxiety: a subdivision of the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1984; 47:970-975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Åsberg M, Montgomery SA, Perris C, Schalling D, Sedvall G: A comprehensive psychopathological rating scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1978; 271:5-27Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Montgomery SA, Åsberg M: A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979; 134:382-389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Sheehan DV: The Anxiety Disease. New York, Bantam Books, 1983Google Scholar

21. Grace J, Stout JC, Malloy PF: Assessing frontal lobe behavioral syndromes with the frontal lobe personality scale. Assessment 1999; 6:269-284Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Schalling DS, Åsberg M, Edman G, Oreland L: Markers for vulnerability to psychopathology: temperament traits associated with platelet MAO activity. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1987; 76:172-182Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Kaplan E, Fein D, Morris R, Delis DC: WAIS-R as a Neuropsychological Instrument (WAIS-R NI). San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp (Harcourt), 1991Google Scholar

24. Wechsler D: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 3rd ed. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp (Harcourt), 1997Google Scholar

25. Lezak MD: Neuropsychological Assessment. New York, Oxford University Press, 1995Google Scholar

26. Heaton RK, Chelune GJ, Talley JL, Kay GG, Curtiss G: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Manual. Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1993Google Scholar

27. Wechsler D: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp (Harcourt), 1981Google Scholar

28. Snaith RP, Harrop FM, Newby DA, Teale C: Grade scores of the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression and the Clinical Anxiety Scales. Br J Psychiatry 1986; 148:599-601Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Jenike MA, Baer L, Ballantine T, Martuza RL, Tynes S, Giriunas I, Buttolph ML, Cassem NH: Cingulotomy for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a long-term follow-up of 33 patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:548-555Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Baer L, Rauch SL, Ballantine HT Jr, Martuza R, Cosgrove R, Cassem E, Giriunas I, Manzo PA, Dimino C, Jenike MA: Cingulotomy for intractable obsessive-compulsive disorder: prospective long-term follow-up of 18 patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:384-392Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Dougherty DD, Baer L, Cosgrove GR, Cassem EH, Price BH, Nierenberg AA, Jenike MA, Rauch SL: Prospective long-term follow-up of 44 patients who received cingulotomy for treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:269-275Link, Google Scholar

32. Nyman H, Andréewitch S, Lundbäck E, Mindus P: Executive and cognitive functions in patients with extreme obsessive-compulsive disorder treated by capsulotomy. Appl Neuropsychol 2001; 8:91-98Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Mindus P, Nyman H: Normalization of personality characteristics in patients with incapacitating anxiety disorders after capsulotomy. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991; 83:283-291Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar