Are Impairments of Action Monitoring and Executive Control True Dissociative Dysfunctions in Patients With Schizophrenia?

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Impaired self-monitoring is considered a critical deficit of schizophrenia. The authors asked whether this is a specific and isolable impairment or is part of a global disturbance of cognitive and attentional functions. METHOD: Internal monitoring of erroneous actions, as well as three components of attentional control (conflict resolution, set switching, and preparatory attention) were assessed during performance of a single task by eight high-functioning patients with schizophrenia and eight comparison subjects. RESULTS: The patients exhibited no significant dysfunction of attentional control during task performance. In contrast, their ability to correct errors without external feedback and, by inference, to self-monitor their actions was markedly compromised. CONCLUSIONS: This finding suggests that dysfunction of self-monitoring in schizophrenia does not necessarily reflect a general decline in cognitive function but is evidence of disproportionately pronounced impairment of action monitoring, which may be mediated by a distinct subsystem within the brain’s executive attention networks.

Self-monitoring, the ability to control self-initiated actions and cognitive processes, is affected by schizophrenia (1–4). An important neurocognitive theory of schizophrenia (1) holds that disturbances of internal monitoring may lead to an inability to distinguish between self-generated and externally triggered activities, which in turn underlie a variety of the symptoms of schizophrenia. These theoretical considerations motivated further investigation of self-monitoring problems in schizophrenia and their relation to general cognitive functioning. The ability to detect and correct one’s errors, a task that demands attention to one’s action, has been linked to problems of internal monitoring processes (2, 3). Dysfunction of self-monitoring might merely reflect a more general failure of attentional mechanisms in schizophrenia or a selective impairment not necessarily related to other cognitive deficits.

Method

Data from eight outpatients who were stable while taking medication (seven men and one woman; six with undifferentiated and two with paranoid subtypes of schizophrenia; mean age=34.1 years, SD=8.0; score on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale: mean=38.3, SD=9.3, range=21.0–51.5) and were diagnosed with schizophrenia on the basis of the DSM-IV Structured Clinical Interview were tested in the Palo Alto Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System. Four others were excluded from participation because of their inability to follow task instructions. Eight age-matched normal comparison subjects from the community (four men and four women; mean age=35.3 years, SD=4.4) were tested in the Martinez VA Health Care System. All subjects gave written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study. Identical equipment and standardized testing conditions were used at both sites.

The behavioral task was modeled after work by Frith and Done (3) and modified to assess simultaneously a number of abilities considered to engage high-level executive-control mechanisms: 1) overcoming response conflicts, 2) flexible task switching, and 3) preparing an appropriate task set (5) while establishing different conditions for the detection and correction of errors. On each trial, the subjects responded with the press of a left- or right-hand button to one of four possible visual target stimuli that were presented 4.25° on either side, above, or below the center of a cathode ray tube display. Stimulus-response mapping of each trial was indicated by a precue presented 1250 or 1750 msec before the target presentation. The next trial started within 2100 msec of the target presentation. Under instructions that emphasized speed and encouraged self-correction of errors with a second response, the subjects followed a 4-to-2 stimulus-to-response mapping that varied randomly across trials. Responses were labeled as compatible, incompatible, or unrelated to the stimulus. Errors could be corrected within a 1600-msec postresponse interval. In alternating blocks, the subjects received either immediate or delayed (800 msec) visual feedback on the accuracy of their responses.

Initial practice established a bias in favor of one of the mappings. Performance on trials with weaker mappings reflected an ability to suppress response bias. Performance on trials when the stimulus-response mapping switched relative to the preceding trial in relation to those in which stimulus-response mappingremained the same assessed mental flexibility. Performance improvement with longer precue intervals assessed preparatory attention.

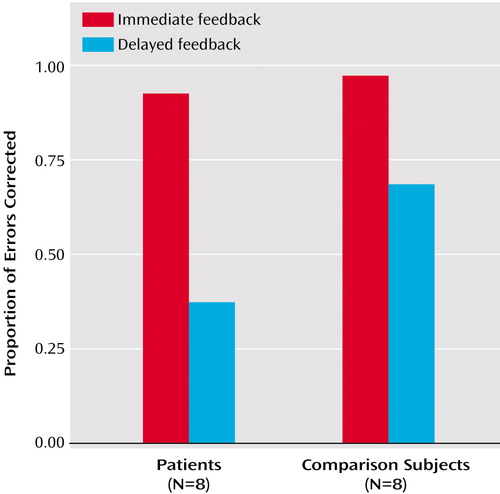

Self-monitoring ability was assessed in comparisons of the proportion of errors corrected within 800 msec in the delayed and immediate feedback conditions. Correction rates in the delayed feedback condition reflected internal detection of errors. Correction rates in the immediate feedback condition assessed compliance with instructions to self-correct and with speed of response.

The subjects completed six blocks of 48 trials (three per feedback condition in alternating order, starting with immediate feedback). Reaction times and accuracy (proportion correct) were analyzed in two-(group)-by-two-(short versus long preparation time)-by-two-(response conflict versus no conflict)-by-two (repeated versus switched tasks) mixed-model repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs). Rates of error correction (within 800-msec postresponse) in the immediate and delayed feedback conditions were compared with a two-(group)-by-two-(feedback type) mixed-factor ANOVA.

Results

Analysis of rates of error correction revealed a robust main effect of feedback type (F=40.95, df=1, 14, p<0.001) and, of importance, an interaction of group by feedback type (F=7.00, df=1, 14, p<0.02). Error-correction rates decreased for both groups when external feedback was not immediately available, but more so for the patients (Figure 1). The patients had lower error-correction rates in the delayed feedback condition (t=–3.12, df=14, p=0.006), even though the two groups had relatively comparable performance on the immediate feedback task (t=–1.55, df=14, p=0.08). Each patient was able to correct some errors without feedback (10% for the two worst performers), and all patients could respond adequately within the critical 800-msec interval during the external feedback task. Therefore, a lack of compliance with task instructions or a general slowing of motor responses was unlikely to account for why patients were selectively deficient with self-initiated error corrections.

In contrast, performance on the three measures of attentional control did not show significant group effects. Despite a lack of group differences, the factors of preparation time, set switching, and response conflict all produced significant main effects for performance accuracy (F=11.30, df=1, 14, p<0.005; F=29.59, df=1, 14, p<0.001; F=7.12, df=1, 14, p<0.02, respectively) and reaction times (F=13.78, df=1, 14, p=0.002; F=3.29, df=1, 14, p<0.10; F=26.06, df=1, 14, p<0.001). Compared to baseline conditions, responses became slower and less accurate in the presence of the following conditions:

| 1. | Conflicting response alternatives. For the comparison subjects, we gathered the following data for immediate and delayed feedback, respectively: reaction time—mean=579 msec, SD=136, versus mean=470 msec, SD=99; proportion correct—mean=80.89%, SD=11.19%, versus mean=86.78%, SD=10.57%. For the patients, the data were as follows: reaction time—mean=618 msec, SD=144, versus mean=547 msec, SD=110; proportion correct—mean=77.16%, SD=9.12%, versus mean=79.34%, SD=8.77%. | ||||

| 2. | Switching between tasks. For the comparison subjects, we gathered the following data: reaction time—mean=536 msec, SD=120, versus mean=512 msec, SD=108; proportion correct—mean=80.23%, SD=13.10%, versus mean=87.44%, SD=8.70%. For the patients, the data were as follows: reaction time—mean=590 msec, SD=134, versus mean=576 msec, SD=115; proportion correct: mean=72.19%, SD=10.14%, versus mean=84.31%, SD=7.66%. | ||||

| 3. | Less time allowed for preparation of the task sets. For the comparison subjects, we gathered the following data: reaction time—mean=543 msec, SD=106, versus mean=506 msec, SD=119; proportion correct—82.14%, SD=11.88%, versus mean=85.54%, SD=9.12%. For the patients, the data were as follows: reaction time—mean=604 msec, SD=110, versus mean=562 msec, SD=136; proportion correct—mean=76.17%, SD=9.31%, versus mean=80.32%, SD=7.63%. | ||||

Of importance, these effects did not vary between groups, either for accuracy (F=0.11, df=1, 14, p=0.75; F=1.90, df=1, 14, p=0.19; and F=1.51, df=1, 14, p=0.24) or reaction time (F=0.05, df=1, 14, p=0.83; F=0.20, df=1, 14, p=0.66; and F=1.12, df=1, 14, p=0.31, respectively).

In order to determine whether the patients might show enhanced conflict effects in a situation in which response bias was not dependent on recent training, we limited our analysis to a subset of trials in which stimuli appeared in a left or right visual hemifield with response required by the opposite hand. These trials provided a measure of automatic response conflict based on spatial incompatibility, which was unconfounded by previous training. No performance decrements for incompatible trials were seen for either accuracy (t=–0.67, df=14, p=0.26) or reaction time (t=–0.61, df=14, p=0.28). These results indicate generally spared attentional control processes in this patient group, in spite of compromised self-monitoring ability, as assessed by error correction rates in the absence of external feedback.

Discussion

The self-monitoring impairment in this patient group, observed in the absence of significant attentional control deficits, argues for a dissociable dysfunction selectively affecting the mechanisms responsible for processing internal representations of one’s own cognitive processes and actions. This pattern would not be expected if the processes of self-monitoring were intimately dependent on the rest of the brain’s attentional networks. Because our group was small and included only relatively high-functioning patients who could perform this complex task, the current report did not permit strong generalizations. However, it did provide novel evidence requiring replication in larger groups and use of new tasks that probe the same cognitive mechanisms that can be performed with relative ease by a majority of the patient population. The possibility suggested by this report that the cognitive architecture of the normal human brain may honor a division between self-monitoring and other higher-level functions requires further investigation of the internal monitoring process, its biological underpinnings, and the nature of its dysfunction in schizophrenia.

Received Jan. 16, 2002; revisions received April 9, 2002, and April 16, 2003; accepted April 28, 2003. From the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine; and the Psychiatry Service, Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, Calif. Address reprint requests to Dr. Ford, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305-5550; [email protected] (e-mail). Funded by NIMH grants MH-40052 and MH-58262 and by the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors thank the patients who participated in this study and Margaret Rosenbloom for her assistance.

Figure 1. Rates of Error Correction, With and Without Immediate External Feedback, Among Patients With Schizophrenia and Healthy Comparison Subjects in a Task Assessing Attentional Controla

aThe task assessed three components: conflict resolution, set switching, and preparatory attention. The patients performed significantly worse than the comparison subjects in the delayed feedback condition only, in which they had to rely solely on self-monitoring of errors.

1. Frith CD: The Cognitive Neuropsychology of Schizophrenia. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1992Google Scholar

2. Malenka RC, Angel RW, Hampton B, Berger PA: Impaired central error-correcting behavior in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:101–107Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Frith CD, Done DJ: Experiences of alien control in schizophrenia reflect a disorder in the central monitoring of action. Psychol Med 1989; 19:359–363Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Carter CS, MacDonald AW III, Ross LL, Stenger VA: Anterior cingulate cortex activity and impaired self-monitoring of performance in patients with schizophrenia: an event-related fMRI study. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1423–1428Link, Google Scholar

5. Posner MI: Attention, the mechanisms of consciousness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994; 91:7398–7403Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar