Lack of Normal Association Between Cerebellar Volume and Neuropsychological Functions in First-Episode Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Functional neuroimaging studies have identified a role for the cerebellum in the neuropsychology of schizophrenia. Few studies, however, have examined the relationship between cerebellar size and neuropsychological functioning in schizophrenia. The authors’ goal was to examine this relationship in patients and healthy comparison subjects. METHOD: Total cerebellar volume was computed from magnetic resonance images in 48 male and 33 female patients experiencing a first episode of schizophrenia and in 14 male and nine female healthy comparison subjects. Patients and comparison subjects completed a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment encompassing six domains of functioning: executive, motor, language, visuospatial, memory, and attention. A global domain of functioning was computed as the mean of these six domains. RESULTS: Larger cerebellar volume correlated significantly with better global functioning in healthy subjects but not among patients with schizophrenia; this relationship was significantly stronger in healthy subjects than in patients. Additional analyses revealed significant associations between cerebellar volume and visuospatial, executive, and memory functions in healthy volunteers but not among patients. CONCLUSIONS: The cerebellum plays a role in higher cognitive functions in healthy individuals, and normal associations between cerebellar size and function are absent in patients experiencing a first episode of schizophrenia. These findings are consistent with neurobiological models implicating the cerebellum in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia.

Positron emission tomography studies suggest that some aspects of healthy neuropsychological functioning involve the cerebellum (1) and that patients with schizophrenia demonstrate abnormal patterns of metabolic activity while performing neuropsychological tasks (2). Despite these studies, however, little is known regarding the possible functional correlates of cerebellar size in either healthy subjects or patients with schizophrenia. Previous studies suggested that larger cerebellar volume is associated with better neuropsychological functioning in healthy subjects (3, 4). Studies conducted with patients suggested that smaller cerebellar volume correlates with greater psychosocial impairment (5) and that smaller vermis volume is associated with greater depression and paranoia (6). Other studies of patients with schizophrenia reported that the anterior vermis area correlates positively with WAIS-R full-scale IQ (7) and that larger vermis white matter volume is correlated with worse logical memory functioning (8).

In the present study we investigated the neuropsychological correlates of cerebellar structure volumes in healthy subjects and patients experiencing their first episode of schizophrenia. We hypothesized that larger cerebellar volume would be associated with better neuropsychological functioning among healthy subjects and that patients would demonstrate an abnormal pattern of structure-function relations.

Method

Forty-eight men and 33 women with a mean age of 25.5 years (SD=6.6) who were experiencing their first episode of schizophrenia were selected from a larger group of 118 patients described previously (9). The 81 patients were selected on the basis of whether they had magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans available for measurement of the cerebellum and whole brain and completed at least one comprehensive neuropsychological assessment. Fourteen men and nine women with a mean age of 25.5 (SD=5.7) who denied a history of neuropsychiatric or medical illness on interview were selected to match the patient group in distribution of age and sex.

Among the 81 patients, 56 were dextral and 25 nondextral; among the 19 healthy volunteers for whom handedness information was available, 13 were dextral and six nondextral. Exclusion criteria for patients and healthy comparison subjects included any history of chronic neurological, endocrine, or medical illness or drug treatment known to affect the brain as determined by interview and supplemented among patients and 19 comparison subjects by Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version interview, physical examination, and urinalysis. All procedures were approved by our institutional review board, and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

MRIs were acquired in the coronal plane by using a three-dimensional gradient-echo fast low-angle-shot sequence with a 50° flip angle, 40-msec repetition time, and 15-msec echo time on a 1.0-T whole-body superconducting Magnetom imaging system (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). This sequence produced 63 contiguous coronal slices through the whole head (slice thickness=3.1 mm). The median number of weeks from the first administration of antipsychotic medication to the MRI examination was 7.9 (range=0 to 262). Scans of patients and comparison subjects were mixed together before measurements. Methods for measuring the whole brain and cerebellum are described elsewhere (10). Interrater reliabilities between two raters (as assessed by intraclass correlations [ICC]) in 10 cases were 0.94 for the cerebellum and 0.96 for the whole brain.

Neuropsychological assessments of patients were conducted following remission or achievement of a stable level of residual symptoms for the preceding 2 weeks as measured by rating scale assessments. The mean number of weeks from the administration of antipsychotic medication to the neuropsychological exam was 43.3 (SD=40.5). The median number of weeks from the MRI examination to the neuropsychological exam was 19.4 (range=–235 to 98) for patients and 0 for healthy volunteers (range=–112 to 300). Administration of the neuropsychological tests was counterbalanced and included 41 tests selected to characterize six domains of neuropsychological functioning: language, attention, memory, executive, motor, and visuospatial (as described previously [11]). A global domain of functioning was computed by averaging these six domains.

Cerebellar volumes were adjusted for the effects of total brain volume, age, and parental social class by using linear regression (10). We first examined cerebellar volume in relation to the global neuropsychological domain to minimize type I error. Because distributions of variables were judged to have a normal shape, two-tailed Pearson product-moment correlations (alpha=0.05) were used for investigation of structure-function relations. We used either independent groups t tests or chi-square analyses to examine group differences in characteristics.

Results

Patients and healthy comparison subjects did not differ significantly in age at the time of the MRI or neuropsychological examinations or in distributions of sex or handedness (p>0.05). Patients, however, had a significantly lower parental social class (χ2=4.3, df=1, p=0.04) and, as expected, fewer years of education (χ2=17.0, df=1, p<0.001) than healthy subjects. Parental social class data were unavailable for one patient and three comparison subjects.

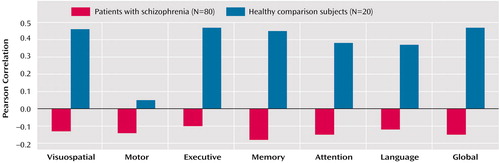

The correlations between cerebellar volume and the neuropsychological domains for patients and healthy comparison subjects are illustrated in Figure 1. These analyses revealed that larger cerebellar volume correlated significantly with better global neuropsychological functioning among healthy comparison subjects (r=0.47, df=20, p=0.04), but not among patients with schizophrenia (r=–0.15, df=80, p=0.20). Cerebellar volume was more strongly correlated with global neuropsychological functioning among healthy subjects than patients (z=2.47, p=0.007). Investigation of the individual neuropsychological domains included in the global domain revealed that among healthy comparison subjects cerebellar volume correlated significantly with visuospatial (r=0.46, df=20, p=0.04), executive (r=0.47, df=20, p=0.04), and memory (r=0.45, df=20, p=0.05) functioning (Figure 1). None of the correlations between cerebellar volume and the individual neuropsychological domains was statistically significant among patients (Figure 1) (all p>0.05). Although there were too few subjects in our healthy comparison group to investigate the possible effects of sex on the observed findings, there were no significant associations of structure and function for either male or female patients (all p>0.05). Global neuropsychological functioning did not correlate significantly with total brain volume among healthy comparison subjects (r=0.08, df=20, p=0.72).

We considered whether the lack of an association between cerebellar volume and neuropsychological functioning in patients might be attributable to changes in medication or temporal-related or illness-related effects that occurred between the exams. We found no evidence, however, for an association between either neuropsychological functioning or cerebellar volume and total cumulative antipsychotic exposure (in chlorpromazine equivalents), changes in illness severity, or the time interval between the exams.

Discussion

Although functional neuroimaging studies have identified a role for the cerebellum in healthy human cognition as well as the neuropsychological deficits observed in schizophrenia, there are few data regarding the functional correlates of cerebellar structure volumes in these groups. Our findings suggest that larger cerebellar volume is associated with better cognitive functioning in healthy subjects, and that these normal structure-function relations are absent among patients experiencing a first episode of schizophrenia studied soon after illness onset and before extensive pharmacological intervention. Moreover, cerebellar volume was more strongly correlated with global neuropsychological functioning among healthy subjects than patients. Total brain volume did not correlate significantly with global functioning in healthy subjects, suggesting that the observed structure-function relations had specificity to the cerebellum.

The finding that larger cerebellar volume was associated with better neuropsychological functioning in healthy subjects is consistent with the results from two previous structural neuroimaging studies. Andreasen et al. (3) found that larger cerebellar volume was associated with better verbal and performance intelligence among 67 healthy subjects. In a new and independent sample of 62 healthy subjects, the same group (4) found that cerebellar volume correlated positively with finger tapping performance, memory retention for complex narrative material, and general intellectual ability. Our findings are also consistent with the results of functional neuroimaging studies that identified cerebellar activation in healthy subjects during the short- and long-term retention of words (1) and during a virtual reality paradigm assessing allocentric memory (12).

The lack of significant structure-function relations in patients is consistent with neurobiological models of schizophrenia that implicate cerebellar dysfunction in the disorder (13) as well as neurological studies implicating cerebellar disease in a “cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome” (14). Previous studies investigating the neuropsychological correlates of cerebellar structure volumes in schizophrenia found relations with the vermis (7, 8); therefore, our findings may not be directly comparable. Our findings may be consistent with previous reports of reduced cerebellar blood flow in patients during the recall of novel and practiced word lists (2). It is conceivable that cerebellar structural alterations in schizophrenia, possibly involving the vermis (6, 7), could either result in or be a cause of inefficient metabolic activity in patients during the performance of cognitive tasks. On the other hand, abnormalities in other brain regions with which the cerebellum is connected might also obscure normal structure-function relations.

Although other structural neuroimaging studies investigating the cerebellum may have used higher magnetic field strengths and a thinner slice thickness, we do not believe that the use of this methodology would have substantively affected computation of total cerebellar volume. A limitation of our imaging methodology, however, was that we did not investigate the cerebellar lobules or discern the functional correlates of either cerebellar gray or white matter volumes.

In summary, this study suggests that the neuropsychological correlates of cerebellar structure volumes observed in healthy humans are absent among patients experiencing a first episode of schizophrenia.

Received Oct. 29, 2002; revision received March 20, 2003; accepted March 31, 2003. From the Department of Psychiatry Research, Zucker Hillside Hospital, North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System N.Y.; the Department of Psychiatry, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, N.Y.; the Department of Radiology, North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System, New Hyde Park, N.Y.; Pfizer Global Research and Development, Groton, Conn.; Pfizer Research Corporation, New York; the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill; and the University of California, Los Angeles, Neuropsychiatric Institute, Geffen School of Medicine, Los Angeles. Address reprints to Dr. Szeszko, Zucker Hillside Hospital, Department of Psychiatry Research, 75-59 263rd St., Glen Oaks, NY 11004; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by NIMH grants MH-41646, MH-41960 (Dr. Lieberman), and MH-01990 (Dr. Szeszko).

Figure 1. Correlations Between Cerebellar Volume and Performance in Six Neuropsychological Domains and a Global Domain for Patients Experiencing Their First Episode of Schizophrenia and Healthy Comparison Subjectsa

aPerformance in the global domain is the mean of the performance in the six individual domains.

1. Andreasen NC, O’Leary DS, Arndt S, Cizadlo T, Hurtig R, Rezai K, Watkins GL, Boles Ponto LL, Hichwa RD: Short-term and long-term verbal memory: a positron emission tomography study. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995; 92:5111–5115Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Crespo-Facorro B, Paradiso S, Andreasen NC, O’Leary DS, Watkins GL, Boles Ponto LL, Hichwa RD: Recalling word lists reveals “cognitive dysmetria” in schizophrenia: a positron emission tomography study. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:386–392Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Andreasen NC, Flaum M, Swayze V II, O’Leary DS, Alliger R, Cohen G, Ehrhardt J, Yuh WT: Intelligence and brain structure in normal individuals. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:130–134Link, Google Scholar

4. Paradiso S, Andreasen NC, O’Leary DS, Arndt S, Robinson RG: Cerebellar size and cognition: correlations with IQ, verbal memory and motor dexterity. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1997; 10:1–8Medline, Google Scholar

5. Wassink TH, Andreasen NC, Nopoulos P, Flaum M: Cerebellar morphology as a predictor of symptom and psychosocial outcome in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 45:41–48Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Ichimiya T, Okubo Y, Suhara T, Sudo Y: Reduced volume of the cerebellar vermis in neuroleptic-naive schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 49:20–27Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Nopoulos PC, Ceilley JW, Gailis EA, Andreasen NC: An MRI study of cerebellar vermis morphology in patients with schizophrenia: evidence in support of the cognitive dysmetria concept. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 46:703–711Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Levitt JJ, McCarley RW, Nestor PG, Petrescu C, Donnino R, Hirayasu Y, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA, Shenton ME: Quantitative volumetric MRI study of the cerebellum and vermis in schizophrenia: clinical and cognitive correlates. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1105–1107Abstract, Google Scholar

9. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, Bilder R, Goldman R, Geisler S, Koreen A, Sheitman B, Chakos M, Mayerhoff D, Lieberman JA: Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:241–247Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Szeszko PR, Gunning-Dixon F, Ashtari M, Snyder PJ, Lieberman JA, Bilder RM: Reversed cerebellar asymmetry in men with first-episode schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 53:450–459Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Bilder RM, Goldman RS, Robinson D, Reiter G, Bell L, Bates JA, Pappadopulos E, Willson DF, Alvir JMJ, Woerner MG, Geisler S, Kane JM, Lieberman JA: Neuropsychology of first-episode schizophrenia: initial characterization and clinical correlates. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:549–559Link, Google Scholar

12. Pine DS, Grun J, Maguire E, Burgess N, Zarahn E, Koda V, Szeszko PR, Bilder RM: Neurodevelopmental aspects of virtual reality navigation: an fMRI study. Dev Psychol 2002; 15:396–406Google Scholar

13. Andreasen NC, Paradiso S, O’Leary DS: “Cognitive dysmetria” as an integrative theory of schizophrenia: a dysfunction in cortical-subcortical-cerebellar circuitry? Schizophr Bull 1998; 24:203–218Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Schmahmann JD, Sherman JC: The cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. Brain 1998; 121(part 4):561–579Google Scholar