Supplementing Clinic-Based Skills Training With Manual-Based Community Support Sessions: Effects on Social Adjustment of Patients With Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Although skills training is a validated psychosocial treatment for schizophrenia, generalization of the skills to everyday life has not been optimal. This study evaluated a behaviorally oriented method of augmenting clinic-based skills training in the community with the aim of improving opportunities, encouragement, and reinforcement for outpatients to use their skills in their natural environment. METHOD: Sixty-three individuals with schizophrenia were randomly assigned to 60 weeks of clinic-based skills training alone or of clinic-based skills training supplemented with manual-based generalization sessions in the community. Patients were also randomly assigned to receive either haloperidol or risperidone. Therapists’ fidelity to the manuals was measured. Patients’ acquisition of the skills from pre- to posttraining was evaluated. The primary outcome measures were the Social Adjustment Scale-II and the Quality of Life Scale. RESULTS: Seventy-one percent of the patients completed the trial. Only six participants experienced psychotic exacerbations during the trial. There was no evidence of a differential medication effect on social functioning. Social functioning improved modestly in both psychosocial conditions over time; participants who received augmented skills training in the community showed significantly greater and/or quicker improvements. CONCLUSIONS: Given judicious and effective antipsychotic medication that limited exacerbations to less than 10% during the trial, a wide range of outpatients with schizophrenia demonstrated substantial learning of illness management and social skills in the clinic. When clinic-based skills training was augmented by in vivo training and consultation, transfer of the skills to everyday life was enhanced. These benefits were established regardless of the medications prescribed.

Training in social and independent living skills is a rehabilitation approach grounded in learning principles in which techniques such as behavioral goal setting, prompting, modeling, shaping, and positive reinforcement are used to teach the interpersonal skills needed by mentally disabled persons to function in the community and develop a satisfying life. More than two decades of quasi-experimental and controlled clinical trials by a variety of investigators have demonstrated that individuals with schizophrenia can learn a wide spectrum of skills (1) that are durable (2, 3) and lead to modest improvements in social functioning (4–7).

Unfortunately, the benefits accruing from psychosocial interventions in general and social skills training in particular are often impeded by obstacles to the adoption of these skills in patients’ everyday life. Some of these generalization obstacles derive from the negative symptoms, positive symptoms, and neurocognitive impairments inherent in schizophrenia. Other impediments to generalization are related to lack of environmental opportunities for using the skills learned in a clinical site and lack of encouragement and reinforcement from community supporters and caregivers.

Despite the many obstacles to generalization of skills training, novel biobehavioral treatments to promote improved social functioning of individuals with schizophrenia in their community life are feasible. New optimism has accompanied the introduction of second-generation antipsychotic medications that are associated with fewer side effects and are better tolerated and thus may permit long-term adherence and engagement in both medication and psychosocial treatments. Since it has been acknowledged that skills training must be provided on a long-term basis to be effective in schizophrenia (6, 7), better tolerated medications should enable individuals to participate for the full duration of their psychosocial services. Development of more effective generalization techniques appears to be a critical next step in strengthening rehabilitation in schizophrenia.

In the current study, stabilized outpatients were randomly assigned to receive clinic-based skills training with or without the addition of manual-based in vivo amplified skills training to promote generalization of the skills in the community. We hypothesized that, compared to participants receiving clinic-based training alone, participants receiving clinic-based training supplemented with in vivo amplified skills training would achieve greater improvements in social adjustment and quality of life. Participants in this study were also randomly assigned to receive either haloperidol or risperidone in a double-blind design. Because of risperidone’s more tolerable side effect profile (8) and its reported advantages in reducing negative symptoms (9), we hypothesized that use of risperidone would also result in greater improvements in social functioning. Findings pertaining to medication effects on side effects, use of side effect agents, dosage, and negative symptoms will be presented in another paper.

Method

Study Setting and Subjects

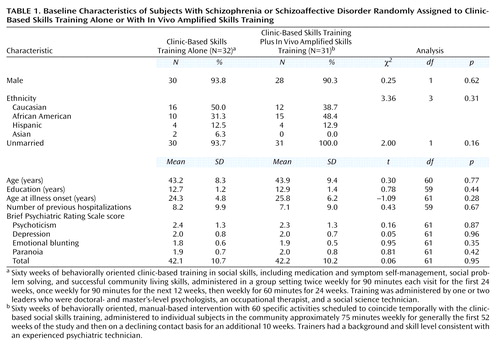

This study was conducted in the Schizophrenia Outpatient Clinic at the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Health Care System at West Los Angeles. This outpatient clinic offers comprehensive psychiatric care provided by a team of psychiatrists, clinical nurse specialists, skills trainers, and case managers. Sixty-three individuals with a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder on the basis of interviews with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (10) participated in the study. Each subject had had at least two documented episodes of acute schizophrenic illness or at least 2 years of continuing psychotic symptoms. Other inclusion criteria included being stablized as an outpatient for at least 1 month, willingness to tolerate haloperidol and risperidone, no significant organic or medical problems precluding learning or regular group attendance, no evidence of substance dependence in the past 6 months, willingness to sign an informed consent form, and age between 18 and 60 years. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects are presented in Table 1.

Procedures

After receiving an initial screening and approval for participation from their current treatment team, potential participants received both a verbal and written description of all study procedures. Written informed consent was obtained from subjects who demonstrated that they were able to comprehend the study procedures, as well as the risks and potential benefits of study participation.

Stabilization and Medication Assignment

After the informed consent procedures, patients entered a 2-month stabilization period during which their current antipsychotic medication was gradually replaced with haloperidol at a dose equivalent to that of the original antipsychotic. To ensure that patients were in a stable condition, subjects were not randomly assigned to the study conditions until they had been followed for at least 2 months during which none of the ratings for items in the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (11) thought disturbance or paranoid clusters changed by more than 1 point. During the 2 weeks just before random assignment, the medication for all patients was changed to 8 mg/day of haloperidol. While the patients were taking this dose, the baseline measurements were obtained. These measurements included scale scores for clinical psychopathology, side effects, and social functioning and the initial skills assessments.

At the time of random assignment to the study conditions, the patients discontinued open-label haloperidol and began double-blind treatment with risperidone or haloperidol. The initial dose of each drug was 2 mg t.i.d. for the first week and then 6 mg at bedtime. Patients were continued on this dose for as long as they remained stable. The only circumstance under which the dose was increased was a psychotic exacerbation. A “psychotic exacerbation” was defined as a worsening from baseline of 4 points or more on the sum of the BPRS cluster scores for thought disturbance and hostile-suspiciousness or an increase of 3 or more points on either of these clusters. In addition, the sum of the scores for at least one of these clusters needed to be 4 or greater. Whenever patients met these criteria, the dose of the study drug could be increased by 2 or 4 mg up to a total daily dose of 16 mg. Patients who had documented extrapyramidal symptoms while receiving only 6 mg of either drug could have their dose lowered to 4 mg and subsequently to a single 2 mg pill at bedtime. After random assignment, attempts were made to lower the dose of and eventually discontinue antiparkinson medications.

Patients who were unable to tolerate their medication condition were removed from the double-blind component of the study and treated with an alternative medication; they were encouraged to remain in the psychosocial treatment, however. Patients who remained in the double-blind haloperidol condition received a mean dose of 4.4 mg daily, and patients treated with risperidone received a mean dose of 5.5 mg.

Progress Through the Protocol

After completing the prestudy stabilization, patients completed an extensive clinical and functional assessment battery and then were randomly assigned to their medication conditions (described earlier) and to receive behaviorally oriented clinic-based social skills training either alone or with the addition of in vivo amplified skills training. Clinic-based skills training was conducted twice weekly for 90 minutes each visit for the first 24 weeks, once weekly for 90 minutes for the next 12 weeks, then weekly for 60 minutes for 24 weeks (a total of 60 weeks of intervention). The additional in vivo amplified skills training was conducted with assigned patients approximately 75 minutes weekly for generally the first 52 weeks of the study and then on a declining contact basis for the last 10 weeks. (Participants in this condition met with the in vivo amplified skills training trainer during the 2–3 weeks before the clinic groups began.) During engagement in treatment, when difficult skills were being taught, and in times of crisis (e.g., unexpected homelessness, family illness), in vivo amplified skills training sessions might be held more than once a week. The entry of new study subjects was timed so that patients could begin the study in cohorts of approximately six to eight patients, with three to four assigned to each condition.

Participants saw their care manager/study coordinator weekly for a brief status check and to receive their study medication. Participants were seen by their study psychiatrist at least monthly for a review of symptoms and side effects, and they completed more extensive symptom and social functioning assessments at 3- and 6-month intervals.

Psychosocial Conditions

Behaviorally oriented clinic social skills training

The procedures for skills training were developed in the University of California, Los Angeles, Clinical Research Center for Schizophrenia and Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Subjects participated in a series of social skills training modules (1) that were administered in a group setting. Subjects participated in modules on medication management and symptom self-management during the first 24 weeks of the trial. A social problem-solving module was completed during the subsequent 12 weeks. Finally, a group focused on successful living skills was completed during the last 24 weeks of the intervention. The social skills training modules were administered by one or two leaders drawn from a team that included doctoral- and master’s-level psychologists, an occupational therapist, and a social science technician.

In vivo amplified skills training

One-half of the participants were randomly assigned to receive in vivo amplified skills training to support use of the behavioral skills in the community. In vivo amplified skills training is a behaviorally oriented, manual-based intervention with 60 specific activities scheduled to coincide temporally with the skills being trained in the clinic, utilizing an overarching problem-solving approach embedded in ongoing assessment. In vivo amplified skills training has four objectives: 1) support completion of clinic assignments in the community, 2) identify opportunities for skill use in the community, 3) reinforce opportunities for skill use in the community, and 4) establish a liaison with or develop a natural support system to maintain gains. Typical in vivo amplified skills training activities included going to a pharmacy to investigate remedies for medication side effects such as dry skin, dry mouth, or photosensitivity; developing a regular daily schedule; identifying the nearest medical facility for use in an emergency; and attending social gatherings to learn to identify and remedy social problems. Depending on their complexity and requirements, one or two tasks were covered in each 75-minute in vivo amplified skills training session. Sessions were held with individual subjects in the community, often in the patient’s home or in a setting conducive to the skill being trained (e.g., a coffee shop for communication skills training, a place with a phone when patients were being taught how to contact a medical worker if they were experiencing side effects). Skills were modeled and prompted by the trainer, who then provided ample social reinforcement for the participant’s rehearsal and eventual successful completion of the skill activity. When addressing any problem, the trainer was encouraged to utilize a social problem-solving model (12). The in vivo amplified skills trainer had a background and skill level consistent with an experienced psychiatric technician.

Supervision and Adherence

Module trainers were supervised in weekly meetings with a master module trainer (K.B.). The supervisor attended one or two randomly selected clinic sessions each month and rated the sessions for adherence to the manual-based micro components of the module, utilizing the Module Fidelity Rating Scale (3). The in vivo amplified skills training supervisor (S.M.G.) met weekly with the trainer to review the patients’ progress and the trainer’s fidelity to the manual. She also went into the community with the trainer at least once with each subject. To assess protocol adherence, the proportion of the 60 scheduled in vivo amplified skills training activities completed was calculated for each participant. Data were derived from contact data sheets completed by the trainer after each session.

Participant Assessments

Assessors were naive to subjects’ psychosocial and medication condition assignments. To assess subjects’ learning of the illness management skills taught in the medication and symptom self-management modules, participants were administered module tests (3, 5) at baseline and at 24 weeks. The tests yielded eight scores reflecting specific skill areas in the modules, as well as two composite scores.

A doctoral-level clinical assessor who was familiar with the patients used the expanded UCLA BPRS (11) to evaluate severity of psychotic and other symptoms at monthly clinic visits. Since the patients were well stabilized at study entry, the average symptom severity scores over the 60-week period showed little change from baseline. For this reason, the principal measure of symptom outcome was psychotic exacerbation, as defined earlier.

Psychosocial outcome was measured by using the patient version of the Social Adjustment Scale-II (13) and the Quality of Life Scale (14). The Social Adjustment Scale-II assesses social functioning by means of a semi-structured interview. The validity of this instrument for use with outpatients with schizophrenia has been previously demonstrated (13). Measures of global adjustment in work role (including student role), household/close family role, extended family role, social and leisure activities, intimate relationships, and overall adjustment, rated on a 1–7 scale, were used in the analyses reported here. The Social Adjustment Scale-II was administered at baseline, 36 weeks, and 60 weeks.

The Quality of Life Scale, a 21-item scale designed to assess the deficit syndrome concept in individuals with schizophrenia, assesses four domains—interpersonal functioning, instrumental role functioning, intrapsychic factors (e.g., motivation, curiosity), and possession of common objects/participation in common activities—and also yields a total score. The mean of the scores for the items included in each of the four factors and the total score were used in the analyses. The Quality of Life Scale was administered at baseline and then every 12 weeks through week 60.

Data Analytic Plan

All statistical tests were two-tailed. To assess skill acquisition, we conducted a series of separate mixed-model analyses of variance (ANOVA) on the change from baseline to week 24 on the eight component skills and the two composite scores, adjusted for the relevant initial score.

Exacerbation episodes were identified, and condition-related statistically significant differences in the proportion of participants experiencing an exacerbation and in the time to exacerbation were evaluated by using chi-square and proportional hazards regression models, respectively.

The data analytic model for the Social Adjustment Scale-II global scores and the Quality of Life Scale factors was the general mixed-model ANOVA with repeated measures. We initially included assigned medication in fully crossed models (design effects for main effects of medication, condition, and time, all two-way intereactions, and an interaction of medication, time, and condition) to test for differential effects on social adjustment. The baseline level was included as a covariate in each analysis. Repeated measures were obtained on the Social Adjustment Scale-II at baseline and two follow-up points (36 and 60 weeks). Each of the global items on the Social Adjustment Scale-II was analyzed separately, as we expected that our intervention might affect some domains (e.g., instrumental role functioning, close family relations) but not others (e.g., relations with extended family, intimate relationships). Repeated measures were obtained on the Quality of Life Scale at baseline and five follow-up points (12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 weeks), permitting the linear effects of time to be included in the statistical model as a within-subject factor. The five factor scores were analyzed separately, as inclusion of linear time effects precludes use of multivariate tests.

Results

Random Assignment, Participation, and Treatment Fidelity

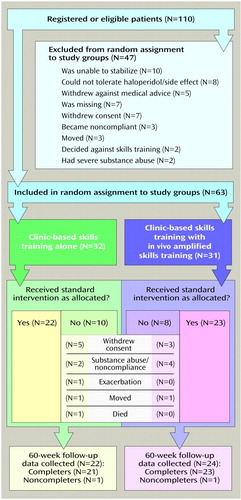

Assignment to intervention condition was not associated with any demographic or clinical variables (all p>0.10) (Table 1). Thirty-two participants were assigned to clinic-based skills training alone; 22 (68.8%) completed treatment. Thirty-one participants were assigned to clinic-based skills training plus in vivo amplified skills training; 23 (74.2%) completed both the group and the in vivo amplified skills training. Progress through the protocol and reasons for noncompletion are outlined in Figure 1. No individual in the clinic-based plus in vivo amplified skills training condition refused only the clinic-based groups or only the in vivo amplified skills training. There were no differences between the conditions in noncompletion, either in absolute rate of noncompletion (χ2=0.22, df=1, p=0.68) or length of time subjects participated before leaving the protocol (log-rank χ2=0.25, df=1, p=0.62). None of the demographic or clinical variables listed in Table 1 predicted noncompletion (all p≥0.10).

There was no difference between the conditions in clinic meeting attendance. Respectively, participants in clinic-based skills training alone and with in vivo amplified skills training attended a mean of 31.38 (SD=10.79) and 34.56 (SD=9.60) medication management sessions (t=1.12, df=50, p=0.13), 34.19 (SD=12.15) and 39.26 (SD=11.46) symptom self-management sessions (t=1.56, df=51, p=0.26), and 19.32 (SD=12.77) and 24.92 (SD=11.54) social problem-solving sessions (t=1.57, df=47, p=0.12). Participants who received in vivo amplified skills training attended a mean of 53.16 (SD=17.88) in vivo amplified skills training meetings.

Overall, the data indicated that the interventions were conducted as prescribed by the manuals. Significant improvements in all eight medication and symptom management skills, as well as the two composite scores, were achieved from pre- to posttraining (all p<0.01) on the module tests. The supervisor’s monthly ratings of randomly selected medication management and symptom self management skills clinic meetings revealed that the facilitators were generally adherent to the skill training manuals. Average scores on the introduction, goal setting, modeling, reaction to difficult situations, quality of instruction, reinforcement, and therapeutic alliance domains were all above 4 on a scale from 1, poor, to 5, excellent, indicating at least “good” skill in training. A review of the in vivo amplified skills training activities summary sheet revealed that across all assigned participants, a mean of 50.87 (SD=16.67, range=0–60) (85%) of the 60 manualized in vivo amplified skills training activities were completed. Among the 23 subjects who completed in vivo amplified skills training, the mean number of in vivo amplified skills training activities conducted rose to 56.96 (SD=5.27, range=53–60) (95%).

Psychotic Exacerbation

Rates of psychotic exacerbations among these stabilized outpatients during the 60-week study period were low. Two of 32 participants receiving clinic-based skills training alone (6.3%) and four of 31 participants receiving clinic-based plus in vivo amplified skills training (12.9%) exhibited psychotic exacerbations. Neither the proportion of participants with psychotic exacerbations (χ2=0.22, df=1, p=0.69) nor the time to exacerbation (log-rank χ2=1.67, df=1, p=0.20) differed between the two groups.

Medications and Social Functioning

We initially included assigned medication in fully crossed models to test for differential effects on social adjustment. With regard to the Social Adjustment Scale-II, these analyses yielded 32 tested effects. None of these were significant at the p<0.05 level, 25 of these had F ratios less than one, and only two unrelated effects utilizing different dependent variables reached the p=0.10 significance level (three would be expected by chance). With regard to the Quality of Life Scale, there were 52 tested design effects. None were significant at the p<0.05 level, 44 of these had F ratios less than one, and only two effects reached the p=0.10 significance level. Taken as a whole, the analyses suggested that no meaningful medication effects existed in these data. Thus, we dropped the medication effects from the models evaluating the psychosocial interventions.

Skills Training Conditions and Social Functioning

As Table 2 shows, participation in clinic-based plus in vivo amplified skills training was associated with significantly greater improvements in instrumental role functioning and close family relationships (group main effect), as well as overall adjustment (condition-by-time interaction), as assessed with the Social Adjustment Scale-II. As Table 3 shows, main effects of time were evidenced on the Quality of Life Scale instrumental role, intrapsychic motivation, common objects, and overall composite scores, reflecting the benefits of participation in the clinic modules. In addition, the pattern of Quality of Life Scale scores suggested that subjects who participated in clinic-based plus in vivo amplified skills training improved more quickly, and often to higher levels, than those in clinic-based skills training alone across the 60 weeks. Responses for the interpersonal, instrumental role, and possession of common objects/participation in common activities domains revealed a significant condition or condition-by-time interaction, as did the overall composite score. Across the two outcome assessment measures, 12 of the 33 tested effects (36%) showed statistically significant differences.

Discussion

The principal advance in treatment provided by this study was the increase and acceleration of the generalization of skills training when clinic-based instruction was augmented by formal practice in the community facilitated by a trainer who used coaching and reinforcement techniques to increase opportunities and encouragement for everyday use of the skills. It is important to note that these benefits were achieved in a group of well-stabilized outpatients, in which the dramatic changes from baseline seen in recovery from more acute episodes would be unlikely. It is probable that the impact of in vivo amplified skills training could be even greater if the procedures were combined with systematic and well-structured programs for family members and others in the patients’ natural support system (15, 16).

The strengths of the design incorporated in the present study included random assignment to treatment, assessors who were naive to treatment assignment, use of manual-based treatments, high levels of supervision to assure adherence to the protocol, and standardized assessments. The primary limitation of this study was the 28% loss to follow-up over 60 weeks, which limited our capacity to conduct intent-to-treat analyses. Clearly, a skills training model requires that patients are present to learn the skill if the training is to have any benefit; patients who leave psychosocial interventions early are precluded from obtaining these benefits. We cannot generalize our findings to these early terminators; for them, even more assertive engagement or better medication stabilization than offered here may be necessary.

When we designed this study, we intended to offer participants the opportunity to stay engaged in the psychosocial component of the study, even if they discontinued the medication to which they were randomly assigned or experienced brief symptom exacerbations. Although we did implement this policy of inclusion, a sizable minority of the subjects were unable to complete the protocol, primarily because of uncontrolled substance abuse (10%), which precluded clinic attendance, or because they withdrew their consent as they no longer wished to attend groups, complete assessments, and/or take medication (13%). Unfortunately, these individuals were usually also lost to follow-up, as they could not be located or refused to participate in assessments. Loss of their data limited our ability to conduct standard intent-to-treat analyses. Confronted with this obstacle, we used maximum likelihood estimates and linear trends when possible in our data analysis, which permitted us to include information from all individuals for whom data were available for at least two time points on each relevant measure. In the current study, 51 participants (81% of the entire study group) contributed sufficient data to permit their inclusion in the analyses. Data from early dropouts could not be incorporated into the analyses, and thus our results cannot be extrapolated to participants who attend only a few weeks of intervention.

Our two psychosocial conditions varied in intensity of intervention; that is, the group who received clinic-based plus in vivo amplified skills training had more contact with a mental health professional (i.e., the in vivo skills trainer) than the group who received only clinic-based skills training. In designing our study, we were forced to weigh the benefits and costs of controlling for the effects of therapist contact by designing a nonspecific community-based intervention to compare with in vivo amplified skills training. Both the economic burden of mounting a second community-based intervention and the findings of our 1996 study (4), which indicated few benefits in social adjustment achieved by participation in a nonspecific treatment, prompted the additive design used here. In our judgment, the effort required to implement and maintain a community intervention for schizophrenia necessitates that it has clear, specific activities and goals similar to those incorporated in the in vivo amplified skills training used in this study.

Certainly, we are aware that some outpatient clinics as currently funded may be constrained from offering the community services we have evaluated here, and it is beyond the scope of this article to evaluate the cost effectiveness of this intervention. Nevertheless, when we designed the intervention, we did keep cost considerations in mind. Our in vivo amplified skills trainer was not a licensed mental health professional; rather, she had a background consistent with a psychiatric technician, which in California includes 1 year of post-high-school training for certification. In addition, the intervention was circumscribed and was never meant to bear the expense (e.g., for 24-hour support or in-home supervisory services) required for some more comprehensive community-based support programs such as assertive case management.

The optimal pharmacotherapy used with the outpatient schizophrenic patients in this study had two major effects. First, our findings demonstrated that low rates of exacerbation or relapse—as well as side effects and attrition—can be achieved with both conventional and atypical antipsychotics. Second, the atypical antipsychotic drug risperidone conferred no particular advantage over haloperidol in the learning and transfer of social skills, even though risperidone has been shown to exert a disproportionately greater benefit over haloperidol for many neurocognitive impairments found in schizophrenia (17–20). The reason for this apparent discrepancy may derive from the different types of schizophrenic populations involved in various studies. Although neurocognition may markedly improve after treatment with risperidone but not with haloperidol, this may only be the case for severely symptomatic and neurocognitively impaired schizophrenic patients who have stable treatment-refractory forms of the disorder (17–20). Alternatively, the relatively low doses of haloperidol used in the present study may not have resulted in intolerable side effects or required the use of memory-inhibiting side effect agents. In such circumstances, both medications would promote apparent engagement in psychosocial treatment.

Well-organized, highly structured skills training, as reflected by the modules of the UCLA Social and Independent Living Skills Program, paired with optimal pharmacotherapy, achieved benefits in social functioning for the participants in this study without the added risk of relapse that sometimes accrues from participation in intensive psychosocial services (21, 22). It is apparently not the frequency or degree of intensity of psychosocial treatment that determines whether it becomes overstimulating and toxic, but rather the organization of the intervention and its ability to harness behavioral learning principles to ensure success and to offer abundant reinforcement at each step in the training process.

To avoid confusing in vivo amplified skills training with assertive community treatment, both of which are intensive services based in the community, it is important to note that in vivo amplified skills training is a learning-based intervention designed to improve specific illness self-management and social skills that are taught in a clinic or other setting. In vivo amplified skills training is intended to improve the everyday use of social and problem-solving skills and to enhance autonomy and social adjustment. Although assertive community treatment could be supplemented by the inclusion of specialist clinicians—including clinic-based skills trainers and in vivo amplified skills trainers—its primary goals have not been to teach skills per se, but rather to stabilize and sustain patients in the community. For example, less than one page in a comprehensive assertive community treatment manual for practitioners (23) was devoted to describing specific skills training and generalization. Thus, although assertive community treatment might be augmented by skills training and in vivo amplified skills training, they are quite dissimilar interventions.

In summary, supporting clinic-based behaviorally oriented instruction with generalization training in the community led to significant posttraining improvements in instrumental role functioning, social relations, and overall adjustment in the study group of stabilized outpatients with schizophrenia. The medications used in this study had no differential impact on social functioning. These benefits were achieved within the context of low rates of psychiatric exacerbation and reflect the importance of planned generalization training in the community to improve the social functioning of persons with schizophrenia.

|

|

|

Presented in part at the International Congress on Schizophrenia, Santa Fe, New Mexico, April 17–21, 1999. Received April 3, 2001; revision received Nov. 13, 2001; accepted Nov. 28, 2001. From the Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles; and the Veterans Affairs (VA) Greater Los Angeles Health Care System. Address reprint requests to Dr. Glynn, VA Greater Los Angeles Health Care System at West Los Angeles (B151J), 11301 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90073; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grant MH-49573 to Dr. Marder. The authors thank Janssen Pharmaceuticals for supplying the risperidone and the matched placebo used in this study.

Figure 1. Steps in Study Protocol Examining Effects on Social Adjustment of Clinic-Based Skills Training Alone or With In Vivo Amplified Skills Training for Subjects With Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective Disorder

1. Liberman RP, Wallace CJ, Blackwell G: Innovations in skills training for the seriously mentally ill: the UCLA Social and Independent Living Skills Modules. Innovations and Research 1994; 2:43-60Google Scholar

2. Eckman TA, Wirshing WC, Marder SR, Liberman RP, Johnston-Cronk K, Zimmermann K, Mintz J: Technique for training schizophrenic patients in illness self-management: a controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1549-1555Link, Google Scholar

3. Wallace CJ, Liberman RP, MacKain SJ, Blackwell G, Eckman TA: Effectiveness and replicability of modules for teaching social and instrumental skills to the severely mentally ill. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:654-658Link, Google Scholar

4. Marder SR, Wirshing WC, Mintz J, McKenzie J, Johnston K, Eckman TA, Lebell M, Zimmerman K, Liberman RP: Two-year outcome of social skills training and group psychotherapy for outpatients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1585-1592Link, Google Scholar

5. Liberman RP, Wallace CJ, Blackwell G, Kopelowicz A, Vaccaro JV, Mintz J: Skills training versus psychosocial occupational therapy for persons with persistent schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1087-1091Link, Google Scholar

6. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Smith TE: Psychiatric rehabilitation, in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 7th ed. Edited by Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Baltimore, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999, pp 3218-3245Google Scholar

7. Heinssen RK, Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A: Psychosocial skills training for schizophrenia: lessons from the laboratory. Schizophr Bull 2000; 26:21-46Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Marder SR, Davis JM, Chouinard G: The effects of risperidone on the five dimensions of schizophrenia derived by factor analysis: combined results of the North American trials. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:538-546Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Marder SR, Meibach RC: Risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:825-835Link, Google Scholar

10. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Administration Booklet. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1997Google Scholar

11. Lukoff D, Liberman RP, Nuechterlein KH: Symptom monitoring in the rehabilitation of schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Bull 1986; 12:578-602Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. D’Zurilla TJ, Goldfried MR: Problem solving and behavior modification. J Abnorm Psychol 1971; 78:107-126Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Schooler NR, Hogarty G, Weissman M: Social Adjustment Scale-II (SAS), in Resource Materials for Community Mental Health Program Evaluations, 2nd ed: Publication ADM 79-328. Edited by Hargreaves W, Attkisson CC, Soreson JE: Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1979, pp 290-302Google Scholar

14. Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT Jr: The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophr Bull 1984; 10:388-398Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Falloon IRH, Held T, Coverdale J, Rocone R, Laidlaw T: Family interventions for schizophrenia: a review of long-term benefits of international studies. Psychiatr Rehabilitation Skills 1999; 3:268-290Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Tauber R, Wallace CJ, Lecomte T: Enlisting indigenous community supporters in skills training programs for persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2000; 51:1428-1432Link, Google Scholar

17. Green MF, Marshall BD Jr, Wirshing WC, Ames D, Marder SR, McGurk S, Kern RS, Mintz J: Does risperidone improve verbal working memory in treatment-resistant schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:799-804Link, Google Scholar

18. Kee KS, Kern RS, Marshall BD, Green F: Risperidone versus haloperidol for perception of emotion in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: preliminary findings. Schizophr Res 1998; 31:159-165Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Kern RS, Green MF, Marshall, BD, Wirshing WC: Risperidone vs haloperidol on reaction time, manual dexterity, and motor learning in treatment-resistant schizophrenia patients. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 44:726-732Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Kern RS, Green MF, Marshall BD, Wirshing WC: Risperidone versus haloperidol on secondary memory: can newer medications aid learning? Schizophr Bull 1999; 25:223-232Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Drake RE, Sederer LI: The adverse effects of intensive treatment of chronic schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry 1986; 27:313-326Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Falloon IRH, Liberman RP: Interactions between drug and psychosocial therapy in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1983; 9:543-554Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Stein LI, Santos AB: Assertive Community Treatment of Persons With Severe Mental Illness. New York, WW Norton, 1998Google Scholar