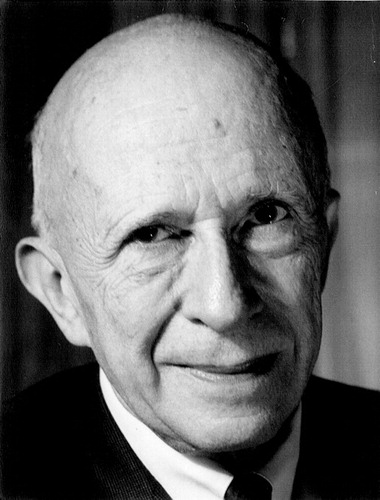

Max Schur, M.D., 1897–1969

Max Schur, best known as Freud’s doctor, exemplifies the complete and modern physician. Trained as an internist and psychoanalyst, he contributed knowledge to both fields, founded two psychosomatic clinics, and explored the connection between psyche and soma in many of his 37 papers as well as in his book, Freud Living and Dying(1). Schur’s career style was emblematic of medicine’s sacred triad of patient care, teaching, and research.

Max Schur was born in 1897 in Stanislaw, then a part of the Austro-Hungarian empire and now part of the Ukraine. Having fled with his family before an advancing Russian army, he completed his secondary and medical education in Vienna. Despite the anti-Semitism in Viennese medical circles, he rose through the ranks as resident, adjunct, and associate in internal medicine at the Vienna Polyclinic, publishing 16 papers on such diverse topics as anemia, hypoglycemia, gastric secretion, and adhesive pericarditis; he also founded a psychosomatic clinic.

As interested in psyche as he was in soma, Schur attended Freud’s introductory lectures on psychoanalysis. Between 1926 and 1932, Schur obtained formal training in psychoanalysis with Ruth Brunswick, a former Freud analysand, while simultaneously practicing internal medicine. Another Freud analysand, Marie Bonaparte, was so impressed with Schur’s medical expertise that she persuaded Freud to make Schur his personal physician. Thus began a doctor-patient relationship in which the bond was so close that Freud included Schur and his family in the Freud party that was given safe passage to London to escape Nazi persecution. Their relationship was based on total honesty and, in Freud’s words, on the promise that “when the time comes, you won’t let me suffer unnecessarily” (1).

After Freud’s death, Schur moved from London to New York. Hospital privileges were scarce for a Jewish immigrant physician in 1939, and Schur accepted his only offer, becoming the internist to the section of syphilology and dermatology at Bellevue Hospital. He capitalized on the opportunity, coauthoring four papers covering various aspects of syphilis and founding another psychosomatic clinic. In 1957, he began to devote himself to psychoanalysis, publishing 16 psychoanalytic papers in such areas as anxiety, the mind-body relationship, affect theory, symptom formation, and the infant-mother relationship. He also served as president of the American Psychoanalytic Association.

Max Schur faced many challenges during his lifetime. His pattern was to find opportunity in adversity, explore new areas in psychiatry and medicine, and champion the crucial connectedness of psyche and soma. His clinical skills included both psychiatry and medicine. During a period when paternalism was common, he modeled, through his treatment of Freud, a modern doctor-patient relationship based on veracity and respect for individual autonomy. He was indeed a complete and modernphysician.

Address reprint requests to Dr. Wittenberg, 2 Medical Center Drive, Suite 410, Springfield, MA 01107.

Max Schur, MD..

1. Schur M: Freud Living and Dying. New York, International Universities Press, 1972Google Scholar