Adequacy of Antidepressant Treatment After Discharge and the Occurrence of Suicidal Acts in Major Depression: A Prospective Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Suicide attempts predict repeat attempts and suicide completion. Major depression requiring hospitalization is a risk factor for suicidal acts, particularly in the 2 years following discharge. The authors prospectively studied the adequacy of antidepressant treatment and its impact on suicidal acts in the 2 years after hospitalization for major depression. METHOD: Patients (N=136) with major depression were interviewed at 3 months, 1 year, and 2 years after admission. At each interview, the presence of major depression and suicidal acts and the adequacy of antidepressant treatment were assessed. Cox’s proportional hazards analysis with time-varying covariates was used to model the risk of a suicide attempt during the follow-up period. RESULTS: Major depression in the follow-up period increased the risk of a suicide attempt sevenfold. For each suicide attempt in a subject’s history, the risk for an attempt in the follow-up period increased by 30%. Antidepressant treatment during the follow-up period was mostly inadequate. Consequently, a relationship between adequacy of antidepressant treatment during follow-up and the risk of a suicide attempt could not be found. Furthermore, subjects with a history of a suicide attempt at baseline were not treated more vigorously than nonattempters. CONCLUSIONS: Antidepressant treatment of depressed patients is strikingly inadequate, even in suicide attempters, known to be at higher risk for suicidal acts. This deficiency undermines the ability to measure the antisuicidal effects of antidepressants in naturalistic studies. Controlled studies of antidepressants are needed to evaluate effects on suicidal acts.

Mental disorders, especially major depression, are a risk factor for suicidal acts. Among subjects with major depression in the community, 16% report having attempted suicide during their lifetimes (1). More than 50% of suicides occur in the context of depressive disorders (2–6).

The risk of suicide attempt or completion following a psychiatric admission is highest in the first 1–2 years after discharge (6–12). Yet little is known about the impact of naturalistic antidepressant treatment on suicide rates after discharge from the hospital after inpatient treatment of depression.

Suicide attempts predict both future suicide attempts and suicide completion (10, 13). Suicide victims with a history of a prior suicide attempt account for 20% to 65% of the deaths by suicide (11). Suicide risk per year for inpatients with a history of attempting suicide is more than twice (14) that of mood-disordered subjects with no history of attempts (12, 15), although some studies have shown this relationship between suicide attempt and subsequent suicide to be restricted to women (9, 16). The relationship between suicide attempts and future attempts has been documented as well. About 50% of attempters in the WHO/Euro Multicentre Study on Parasuicide had a history of at least one previous suicide attempt (17).

Surprisingly, despite the increase in antidepressant prescription rates from 1988 to 1998, suicide rates have declined only 9% in the United States. This implies that either antidepressants are not very effective in preventing suicide or that most patients with depression are inadequately treated.

We prospectively studied the adequacy of antidepressant treatment for patients with and without a history of suicide attempts and its impact on suicidal acts in the 2 years after hospitalization for treatment of an episode of major depression. Antidepressant treatment was naturalistically delivered by physicians in the community. We predicted that patients who received more intensive antidepressant treatment or had less time in a major depressive episode after discharge from the hospital would be at lower risk for suicidal acts during the follow-up period.

Method

Subjects

The subjects were 136 inpatients who were admitted for treatment to one of two university hospitals (in New York City and Pittsburgh) and who met the DSM-III-R criteria for a unipolar major depressive disorder, according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (18). The exclusion criteria were neurological illness or insult, an active medical condition, or substance or alcohol abuse or dependence within 6 months of admission. All subjects provided written informed consent as required by the institutional review board of each hospital.

Data Collection

Upon hospital admission (baseline), all patients had a physical examination, routine blood tests, and urine toxicological tests. Demographic characteristics and history of previous depressive episodes and treatment were documented. Lifetime history of suicide attempts was recorded on the Columbia Suicide History form (19). Interrater reliability is adequate for this instrument (intraclass coefficient=0.97). Suicidal ideation was rated on the Scale for Suicide Ideation of Beck et al. (20). Depressive symptoms were rated with the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (21) and the Beck Depression Inventory (22). Axis II diagnoses were made by means of the Personality Disorder Examination (23) or the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (24).

After hospital discharge, the patients received treatment in the community, and follow-up visits were at 3, 12, and 24 months postdischarge. At each follow-up visit, a doctoral-level clinician (B.S.B. or another) interviewed the patient. Medication name and dose, treatment duration, presence of a major depressive episode and its duration, and any suicide attempts since the last assessment were documented.

The adequacy of antidepressant treatment was assessed by using the Antidepressant Treatment History Form (25). This instrument is used to score the adequacy of treatment trials for major antidepressant medication categories and ECT on a scale from 0 to 5 and has good reliability and validity (25, 26). A score of 3 or above is considered adequate treatment unless the patient responds to a lower dose. In this study, adequacy was based on the calculated score for adequacy, rather than treatment response.

The minimum duration of an adequate antidepressant trial is defined as 4 weeks. Minimum adequate daily doses are 200 mg of imipramine hydrochloride, amitriptyline, desipramine, trimipramine, clomipramine, maprotiline, doxepin, or nomifensine; 76 mg of nortriptyline; 41 mg of protriptyline; 20 mg of paroxetine, fluoxetine, or citalopram; 200 mg of fluvoxamine; 100 mg of sertraline; 61 mg of phenelzine; 41 mg of selegiline, tranylcypromine, or isocarboxazid; 300 mg of moclobemide; 30 mg of mirtazapine; 225 mg of venlafaxine; 300 mg of nefazodone or bupropion; and 400 mg of trazodone. For ECT, the minimum is defined as more than six unilateral or bilateral treatments (see reference 24 for details). Both duration and dose must be adequate for the trial to be classified as adequate. Treatments using a combination of antidepressants are rated according to the highest rating given to the individual antidepressants that are combined, except in the case of lithium augmentation, when a rating of 3 or 4 is increased by 1 point.

Data Analysis

During the follow-up period, the time-varying data were the adequacy of antidepressant treatment and the presence or absence of major depression. These data were used to divide the follow-up period into epochs. The first epoch started the day after discharge from the inpatient unit and continued until the time-varying data changed. A new epoch started whenever there was a change in adequacy of antidepressant treatment, a change in depression status (present or absent), or both. Thus, each epoch has a constant clinical state (presence or absence of depression) and a constant treatment adequacy rating. A suicidal act, withdrawal from the study, or completion of the 2-year follow-up period marked the end of the final epoch.

Cox’s proportional hazards analysis with time-varying covariates was used to model the risk of a suicide attempt during the follow-up period. This analysis provides a hazard ratio for subjects in two groups. The hazard ratio at time t is the ratio of the probabilities that two given subjects, one from each group, having not made an attempt in t days since discharge, will make an attempt shortly thereafter. Under the proportional hazard assumption, which is compatible with our data, this ratio is constant in time.

Two models were constructed. The first model examined baseline characteristics to determine whether variables cited as predictors in the literature (sex, age, and total lifetime number of suicide attempts at study entry) identified subjects likely to attempt suicide in the future. The interaction between age and number of lifetime attempts was also entered into the model. A second model contained baseline variables found to be significant in the first model (age and total lifetime number of suicide attempts at study entry) and the time-varying covariates, namely intensity of antidepressant treatment, depression status (major depression present or absent in each month since last evaluation), and their interaction.

Two-sample t tests were used to compare the average intensity of treatment in the follow-up period for subjects with a baseline suicide attempt and subjects with no baseline suicide attempt; comparisons were made for the follow-up period as a whole, periods of active depression, and periods free of depression. Further, because of the additional risk for suicidal behavior conferred by borderline personality disorder, we compared the adequacy of treatment during the follow-up period for patients with and without comorbid borderline personality disorder.

Results

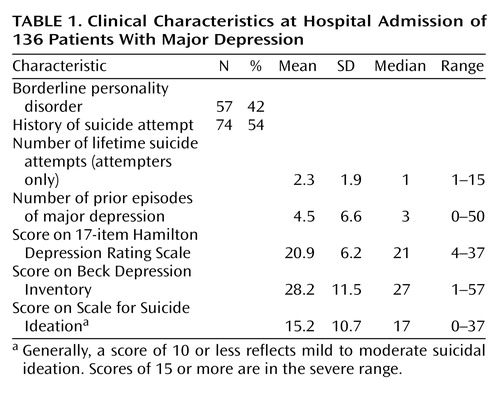

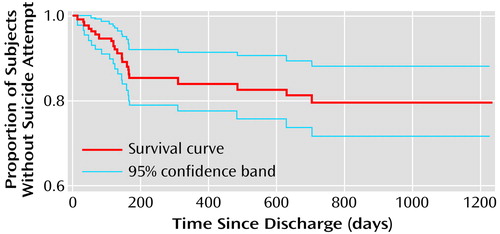

The patients had a mean age of 38.1 years (SD=11.7, median=36.5, range=18 to 72), 36% were male (N=49), 82% were Caucasian (N=111), and 33% had a high school education or less (N=45). Clinical characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1. The subjects were moderately depressed and had prominent suicidal ideation. The follow-up rates were 84% at 3 months (N=114), 76% at 12 months (N=104), and 64% at 24 months (N=87). Twenty-one (15%) of the 136 subjects attempted suicide during the follow-up period. None of the attempts was fatal. More than 50% of the attempts occurred within 5 months of discharge. For the attempters, the median time from hospital discharge until a suicidal act was 132 days (mean=185.1, SD=191.2, range=14–704 days) (Figure 1).

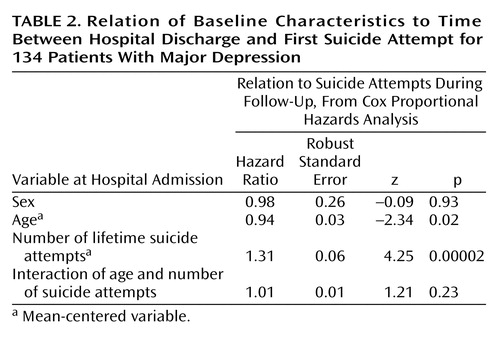

The first model, which included age, sex, lifetime number of suicide attempts at baseline, and interaction between age and number of suicide attempts, showed significant predictive power for suicide attempts during the follow-up period (Table 2). For each lifetime suicide attempt at baseline, the risk of suicide attempts in the follow-up period increased by about 30%; the 95% confidence interval (CI) was 16% to 48%. For each year of age, the risk of a suicide attempt in the future decreased. Thus, older patients were less likely to reattempt suicide than were younger patients who had made the same number of previous suicide attempts. In the second model (Table 3), the risk of a suicide attempt was 7.23 times as high (95% CI=1.7–30.9) for patients who experienced a major depressive episode in the follow-up period. Previous suicide attempts were a significant predictor and increased the risk of an attempt during follow-up in this model also. We found no relationship between the adequacy of antidepressant treatment during the follow-up period and the risk of making a suicide attempt in the 2 years after discharge (Table 3). However, antidepressant treatment during the follow-up period was rated inadequate both during most epochs and on average for the total study group (mean rating=2.1, SD=1.4). Moreover, 18 patients (13%) received no psychopharmacologic treatment during the entire follow-up period. Of those who were treated, the mean rating for treatment was 2.5 (SD=1.2, median=2.5), below the minimum for adequate treatment. Following are examples of mean daily antidepressant doses, in milligrams: desipramine, 177.0 (SD=93.3); bupropion, 284.8 (SD=122.9); fluoxetine, 32.9 (SD=19.2); sertraline, 120.7 (SD=49.8); paroxetine, 42.5 (SD=19.4); nefazodone, 175.0 (SD=35.4); citalopram, 38.3 (SD=20.4); mirtazapine, 88.1 (SD=87.5); and phenelzine, 45.0 (SD=22.5). One subject received 200 mg/day of fluvoxamine. Nine (43%) of the 21 subjects who attempted suicide were receiving adequate antidepressant treatment (i.e., had scores of 3 or higher on the Antidepressant Treatment History Form).

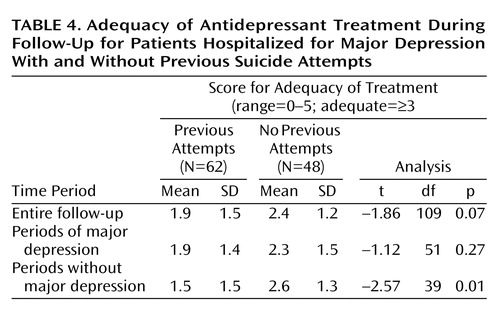

Subjects with a history of suicide attempts at baseline were not treated more vigorously during follow-up than nonattempters (Table 4). Furthermore, the intensity of treatment during periods of major depression in the follow-up phase was similar to the adequacy of treatment during the entire follow-up period, although slightly higher than during the nondepressed periods (Table 4). The presence or absence of comorbid borderline personality disorder was not related to the adequacy of antidepressant treatment; the mean rating of adequacy of treatment was 2.1 (SD=1.5) for subjects with borderline personality disorder and 2.2 (SD=1.4) for those without it (t=–0.39, df=104, p=0.70). When we added borderline personality disorder as a predictor in the survival analysis that included age, sex, and number of previous suicide attempts, borderline personality disorder did not predict suicide attempts during the follow-up period (hazard ratio=1.35, SE=0.25, p=0.23).

Discussion

Relapse or recurrence of major depression increased the risk of suicide attempt during the 2 years after discharge from the hospital, underlining the importance of optimal maintenance antidepressant treatment as a suicide prevention strategy. We were unable to demonstrate that pharmacotherapy of major depression protected patients against suicide attempts in this naturalistic prospective study. One explanation is the overall undertreatment of depression, which undermines the statistical power to measure the benefit of treatment. We found that nine (43%) of the 21 follow-up suicide attempts occurred while patients were receiving adequate treatment. Of those 21 patients, four were depressed at the time of their attempts despite adequate treatment, suggesting that treatment resistance is important. However, little attention has been given in the literature to the role of treatment-resistant depression in suicidal behavior (27). The significance of the inadequacy of the treatment in this study is heightened by the fact that 54% of our inpatient group reported having made a suicide attempt before study entry and thus were at high risk for future suicide attempts. Nonetheless, the suicide attempters were not treated more aggressively than nonattempters. The undertreatment was not explained by the presence of borderline personality disorder, which could have caused diagnostic complications. The presence of borderline personality disorder had no effect on treatment adequacy. Moreover, in the previous attempters, the appearance of a major depressive episode during follow-up did not trigger more intense pharmacologic treatment.

The small number of suicide attempts during follow-up and possible confounds, such as psychotherapy received during follow-up, may have hampered detection of an effect of antidepressant treatment on suicide attempt rates during the follow-up period. Studies directly examining the effects of antidepressant medication on suicidal behavior suggest a role for somatic treatments in the prevention of suicidal acts. In a meta-analysis by Montgomery et al. (28), paroxetine reduced the frequency of completed suicide and suicidal thoughts more than did placebo or other active antidepressant treatment, but it did not reduce the number of suicide attempts. Similarly, in the National Institute of Mental Health collaborative depression study (N=643) there was 56% less risk for suicidal acts among patients taking fluoxetine than among patients receiving no somatic therapy, but this finding was not statistically significant, possibly because of clinical differences in illness severity and suicide history in the subjects treated with fluoxetine (29). In addition, of the subjects treated with fluoxetine, the proportion with suicidal behavior was significantly reduced from 38.9% before fluoxetine treatment to 3.8% during fluoxetine treatment. In contrast, Khan et al. (30) recently reported a meta-analysis that showed that placebo and active antidepressant treatment did not differ in their effects on rates of suicide attempts and completions. However, they studied subjects entered into phase II or III trials for new antidepressants that were ultimately approved by the Food and Drug Administration, and the subjects were selected so as to exclude the comorbidity or acute suicidality often seen in clinical populations. The strongest evidence for psychopharmacologic protection against suicidal behavior comes from controlled and naturalistic treatment studies of lithium and suicidal behavior (31–33). These studies suggest that lithium has an antisuicidal effect independent of its mood-stabilizing properties. Because many of the aforementioned studies were carried out in lithium clinics, where blood serum lithium levels are routinely monitored and noncompliance easily identified, it is possible that part of the robustness of lithium’s antisuicidal properties is due to compliance and not necessarily specific to lithium. At least one study has shown such an effect (34). In the current study, whether inadequate treatment was due to patients’ difficulties with compliance was not determined. Nonetheless, these studies support the notion that pharmacotherapy can have antisuicidal effects.

Improved identification of major depression and more widespread prescription of antidepressant medications appear to be associated with declining rates of completed suicide as well. In Hungary and Sweden, suicide rates show a negative correlation with rates of treated depression (35) and antidepressant prescription rates (36). The Gotland study (37) showed an increase in antidepressant prescription rates and a reduction of suicide rates after an educational program for general practitioners about the diagnosis and treatment of mood disorders. Conversely, lack of treatment of major depression has been associated with increased suicide risk. In Sweden, Isacsson et al. (36) reported that suicide risk among untreated depressed patients was 1.8 times higher than for those treated with antidepressants. In addition, postmortem studies have shown that major depression in suicide victims is infrequently diagnosed and ineffectively treated before death. Isacsson et al. (38) examined data from toxicological screens of 5,281 suicide victims in Sweden and detected antidepressants in only 12.4% of the men and 26.2% of the women. In the San Diego Study (39), half of the depressed suicide victims had consulted a physician in the 90 days before suicide, yet fewer than half of those were given prescriptions for antidepressants. Furthermore, toxicological tests revealed an absence of antidepressants in more than half of subjects for whom they were prescribed. Similarly, in Finland, Isometsä et al. (40) found that although 45% of suicide victims with major depression were receiving psychiatric treatment at the time of death, only 6% had received antidepressants or electroconvulsive therapy in adequate doses.

This naturalistic prospective study of major depression and suicidal acts during a 2-year follow-up period after hospitalization for a major depressive episode showed clinically serious undertreatment of depression. This was so even for patients with a history of suicide attempts, who are at a higher risk for future suicidal acts. In fact, we found that for each lifetime suicide attempt at baseline, the risk of suicide attempts in the follow-up period increased by about 30%. Poor treatment of depression during follow-up has been reported (41–43). In our previous retrospective study of patients seeking treatment at our center for major depression (44), we found that they were strikingly undertreated, regardless of their past history of suicide attempts. The present prospective study demonstrates a continuation of that practice of undertreatment after discharge from inpatient hospitalization for major depression, even for those at high risk for suicidal behavior. These findings are in agreement with the results of a study of 73 patients hospitalized after suicide attempts (28). Using a similar statistical analytic technique but a different patient group, Leon et al. (29) determined that for each additional prior suicide attempt, the risk of a suicide attempt in the follow-up period increased by 32%. Thus, both of these studies reveal that the hazard for suicidal acts in the follow-up period increases as a function of the number of suicide attempts before the index hospitalization, and they indicate that clinicians should obtain this information to assess risk (45). We have also confirmed our retrospective finding that suicide attempters and nonattempters are undertreated (44).

The crucial issue remains unresolved, namely, why is depression undertreated and how can this be corrected? The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the treatment of depression (46) proposes several reasons for undertreatment. They include patient-based reasons, such as reluctance to seek treatment due to failure to recognize symptoms, fear of stigma, and limited access to health care, and provider-based factors, such as poor professional school education about depression, failure to consider psychotherapeutic approaches, lack of parity in insurance coverage for psychiatric illness, and prescription of inadequate doses of antidepressants for inadequate durations (46). Nonetheless, undertreatment of depression may explain the relatively small decline in the suicide rate in the United States, compared with Sweden (36, 47, 48), despite the development of newer, better tolerated, and safer antidepressant medications in the United States. Indeed, in 1995 antidepressant prescriptions were filled for about 33 per 1,000 persons in Sweden (48), 38% more than in the United States, where prescriptions were filled for approximately 24 per 1,000 persons (data from National Prescription Audit, a commercial database maintained by Information Marketing Systems Health America, Plymouth Meeting, Pa.). Perhaps Sweden’s government-funded national health care system imposes fewer obstacles to payment for mental health care than the U.S. system.

A major depressive episode during the follow-up period emerges as the most robust predictor of suicide attempts in our study and emphasizes the need for better diagnosis and treatment of major depression. The efficacy of educational programs should be tested in the United States and elsewhere, targeting not only general practitioners but also psychiatrists, other medical specialists, and primary care physicians. Future studies of antidepressants and their effects on suicidal acts should also include controlled treatment for high-risk patients, with monitoring of blood levels (where appropriate), so that the adequacy of antidepressant prescriptions can be ensured and the effect of pharmacologic treatment on suicidal behavior can be assessed.

|

|

|

|

Received Aug. 15, 2001; revisions received Jan. 22 and April 25, 2002; accepted May 7, 2002. From the New York State Psychiatric Institute and the Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. Address reprint requests to Dr. Oquendo, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Unit 42, 1051 Riverside Dr., New York, NY 10032; [email protected]. Supported by NIMH grants MH-48514 and MH-62185. The authors thank Batsheva Halberstam for editorial assistance.

Figure 1. Estimated Survival Curve Indicating Number of Days Between Hospital Discharge and First Suicide Attempt for 136 Patients With Major Depression

1. Chen Y-W, Dilsaver SC: Lifetime rates of suicide attempts among subjects with bipolar and unipolar disorders relative to subjects with other axis I disorders. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 39:896-899Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Barraclough B, Bunch J, Nelson B, Sainsbury P: One hundred cases of suicide: clinical aspects. Br J Psychiatry 1974; 125:355-373Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Dorpat TL, Ripley HS: A study of suicide in the Seattle area. Compr Psychiatry 1960; 1:349-359Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Carlson GA, Rich CL, Grayson P, Fowler RC: Secular trends in psychiatric diagnoses of suicide victims. J Affect Disord 1991; 21:127-132Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Henriksson MM, Aro HM, Marttunen MJ, Heikkinen ME, Isometsä ET, Kuoppasalmi KI, Lönnqvist JK: Mental disorders and comorbidity in suicide. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:935-940Link, Google Scholar

6. Hagnell O, Rorsman B: Suicide in the Lundby study: a comparative investigation of clinical aspects. Neuropsychobiology 1979; 5:61-73Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Black DW, Winokur G: Prospective studies of suicide and mortality in psychiatric patients. Ann NY Acad Sci 1986; 487:107-113Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Fawcett J, Scheftner W, Clark D, Hedeker D, Gibbons R, Coryell W: Clinical predictors of suicide in patients with major affective disorders: a controlled prospective study. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:35-40Link, Google Scholar

9. Berglund M, Nilsson K: Mortality in severe depression: a prospective study including 103 suicides. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1987; 76:372-380Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Borg SE, Ståhl M: Prediction of suicide: a prospective study of suicides and controls among psychiatric patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1982; 65:221-232Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Dorpat TL, Ripley HS: The relationship between attempted suicide and committed suicide. Compr Psychiatry 1967; 8:74-79Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Nordström P, Åsberg M, Aberg-Wistedt A, Nordin C: Attempted suicide predicts suicide risk in mood disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1995; 92:345-350Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Duggan CF, Sham P, Lee AS, Murray RM: Can future suicidal behaviour in depressed patients be predicted? J Affect Disord 1991; 22:111-118Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Bostwick JM, Pankratz VS: Affective disorders and suicide risk: a reexamination. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1925-1932Link, Google Scholar

15. Fawcett J, Scheftner WA, Fogg L, Clark DC, Young MA, Hedeker D, Gibbons R: Time-related predictors of suicide in major affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1189-1194Link, Google Scholar

16. Brådvik L, Berglund M: Risk factors for suicide in melancholia: a case-record evaluation of 89 suicides and their controls. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1993; 87:306-311Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Bille-Brahe U, Kerkhof A, De Leo D, Schmidtke A, Crepet P, Lönnqvist J, Michel K, Salander-Renberg E, Stiles TC, Wasserman D, Aagaard B, Egebo H, Jensen B: A repetition-prediction study of European parasuicide populations: a summary of the first report from part II of the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Parasuicide in cooperation with the EC Concerted Action on Attempted Suicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997; 95:81-86Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Version 1.0 (SCID-P). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

19. Oquendo MA, Halberstam B, Mann JJ: Risk factors for suicidal behavior: the utility and limitations of research instruments, in Standardized Assessment for the Clinician. Edited by First MB, (Review of Psychiatry, vol 22, Oldham JM, Riba MB, series editors). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press (in press)Google Scholar

20. Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A: Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol 1979; 47:343-352Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56-62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561-571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Loranger AW, Susman VL, Oldham JM, Russakoff LM: The Personality Disorder Examination: a preliminary report. J Personal Disord 1987; 1:1-13Crossref, Google Scholar

24. First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II), version 2. New York, New York Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1996Google Scholar

25. Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Devanand DP, Decina P, Kerr B, Malitz S: The impact of medication resistance and continuation pharmacotherapy on relapse following response to electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1990; 10:96-104Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Prudic J, Haskett RF, Mulsant B, Malone KM, Pettinati HM, Stephens S, Greenberg R, Rifas SL, Sackeim HA: Resistance to antidepressant medications and short-term clinical response to ECT. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:985-992Link, Google Scholar

27. Oquendo MA, Malone KM, Mann JJ: Suicide: risk factors and prevention in refractory major depression. Depress Anxiety 1997; 5:202-211Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Montgomery SA, Dunner DL, Dunbar GC: Reduction of suicidal thoughts with paroxetine in comparison with reference antidepressants and placebo. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1995; 5:5-13Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Leon AC, Keller MB, Warshaw MG, Mueller TI, Solomon DA, Coryell W, Endicott J: Prospective study of fluoxetine treatment and suicidal behavior in affectively ill subjects. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:195-201Abstract, Google Scholar

30. Khan A, Warner HA, Brown WA: Symptom reduction and suicide risk in patients treated with placebo in antidepressant clinical trials: an analysis of the Food and Drug Administration database. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:311-317Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Modestin J, Schwarzenbach F: Effect of psychopharmacotherapy on suicide risk in discharged psychiatric inpatients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992; 85:173-175Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Müser-Causemann B, Volk J: Suicides and parasuicides in a high-risk patient group on and off lithium long-term medication. J Affect Disord 1992; 225:261-270Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, Hennen J, Floris G, Silvetti F, Tohen M: Lithium treatment and risk of suicidal behavior in bipolar disorder patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:405-414Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Kallner G, Lindelius R, Petterson U, Stockman O, Tham A: Mortality in 497 patients with affective disorders attending a lithium clinic or after having left it. Pharmacopsychiatry 2000; 33:8-13Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Rihmer Z, Barsi J, Veg K, Katona CLE: Suicide rates in Hungary correlate negatively with reported rates of depression. J Affect Disord 1990; 20:87-91Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Isacsson G, Bergman U, Rich CL: Epidemiological data suggest antidepressants reduce suicide risk among depressives. J Affect Disord 1996; 41:1-8Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Rutz W, Von Knorring L, Walinder J: Long-term effects of an educational program for general practitioners given by the Swedish Committee for the Prevention and Treatment of Depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992; 85:83-88Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Isacsson G, Holmgren P, Druid H, Bergman U: Psychotropics and suicide prevention: implications from toxicological screening of 5,281 suicides in Sweden 1992-1994. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174:259-265Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Isacsson G, Bergman U, Rich CL: Antidepressants, depression and suicide: an analysis of the San Diego study. J Affect Disord 1994; 32:277-286Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Isometsä ET, Henriksson MM, Aro HM, Heikkinen ME, Kuoppasalmi KI, Lönnqvist JK: Suicide in major depression. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:530-536Link, Google Scholar

41. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Klerman GL, Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Coryell W, Fawcett J, Rice JP, Hirschfeld RM: Low levels and lack of predictors of somatotherapy and psychotherapy received by depressed patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:458-466Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Keller MB, Klerman GL, Lavori PW, Fawcett JA, Coryell W, Endicott J: Treatment received by depressed patients. JAMA 1982; 248:1848-1855Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Friedman R, Kocsis JH, Chen J-S, Mann JJ: Antidepressant treatment intensity in patients with nonbipolar major depression. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1992; 43:83-84Medline, Google Scholar

44. Oquendo MA, Malone KM, Ellis SP, Sackeim HA, Mann JJ: Inadequacy of antidepressant treatment for patients with major depression who are at risk for suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:190-194Abstract, Google Scholar

45. Sidley GL, Calam R, Wells A, Hughes T, Whitaker K: The prediction of parasuicide repetition in a high-risk group. Br J Clin Psychol 1999; 38:375-386Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Hirschfeld RMA, Keller M, Panico S, Arons BS, Barlow D, Davidoff F, Endicott J, Froom J, Goldstein M, Gorman JM, Guthrie D, Marek RG, Maurer TA, Meyer R, Philips K, Ross J, Schwenk TL, Sharfstein SS, Thase ME, Wyatt RJ: The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA 1997; 277:333-340Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. La Vecchia C, Lucchini F, Levi F: Worldwide trends in suicide mortality, 1955-1989. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 90:53-64Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Isacsson G: Suicide prevention—a medical breakthrough? Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000; 102:113-117Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar