Memory Performance in Holocaust Survivors With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors evaluated memory performance in Holocaust survivors and its association with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and age. METHOD: Memory performance was measured in Holocaust survivors with PTSD (N=31) and without PTSD (N=16) and healthy Jewish adults not exposed to the Holocaust (N=35). Explicit and implicit memory were measured by paired-associate recall and word stem completion, respectively. RESULTS: The groups did not differ by age or gender, but the survivors with PTSD had significantly fewer years of education and had lower estimated IQs than the survivors without PTSD and the nonexposed group. There was a significant overall group effect for paired-associate recall but not word stem completion. The survivors with PTSD recalled fewer semantically unrelated words than did the survivors without PTSD and the nonexposed group and fewer semantically related words than the nonexposed group. Of the survivors with PTSD, 36% performed at a level indicative of frank cognitive impairment. Older age was significantly associated with poorer paired-associate recall in the survivors with PTSD but not in the other two groups. CONCLUSIONS: Markedly poorer explicit but not implicit memory was found in Holocaust survivors with PTSD, which may be a consequence of or a risk factor for chronic PTSD. Accelerated memory decline is one of several explanations for the significantly greater association of older age with poorer explicit memory in survivors with PTSD, which, if present, could increase the cognitive burden of this illness with aging.

In the early aftermath of the Holocaust, an array of neuropsychological problems was described in survivors, including anxiety, sleeplessness, and poor concentration and memory. The severity and persistence of these symptoms led to the idea that the “Concentration Camp Syndrome” was an organic brain syndrome associated with premature aging and dementia (1). Despite the passage of over 50 years, a considerable proportion of Holocaust survivors still suffers from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other neuropsychological consequences of the Holocaust (2, 3). The question arises as to whether these survivors have memory impairment and whether it is associated with PTSD or aging.

Normal aging is associated with worsening memory performance, but persons differ in the rate and magnitude of decline. Stress and depression are among the factors that mediate cognitive decline (4–7); therefore, it is of interest to learn whether trauma exposure or PTSD is associated with age-related memory impairment. Poorer verbal memory has been found in some (8–11) but not all (12–14) studies of chronic PTSD but has not been systematically studied in older trauma survivors. Studying Holocaust survivors who span a wide range of ages affords us a unique opportunity to evaluate the extent to which PTSD or exposure to the Holocaust is associated with memory performance in later life.

Explicit and implicit memory performance were studied in Holocaust survivors and healthy Jewish adults with no Holocaust exposure. Explicit memory requires conscious, effortful recollection (15). It is critically dependent on the hippocampus and sensitive to the effects of stress and aging (7, 16–18). Implicit forms of memory, such as procedural memory and priming effects, do not depend on conscious recollection and are relatively insensitive to aging and hippocampal impairment (7, 17). Therefore, we hypothesized that Holocaust survivors with PTSD would have poorer explicit, but not implicit, memory performance than comparison subjects and that performance differences would be more marked with advanced age.

Method

Subjects

The Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board approved this study. Subjects were survivors of the Nazi Holocaust (N=47) or healthy Jewish adults with no exposure to the Holocaust or other extreme traumas (N=35). They were recruited through synagogues and community centers in New York and Quebec and the Specialized Treatment Center for Holocaust Survivors at the Mount Sinai Hospital. English was the native language for most of the nonexposed subjects but none of the survivors. All survivors were proficient in English, and the majority of nonexposed subjects, like the survivors, were bilingual or multilingual (23% were from Quebec and spoke French and English, and many were observant Jews who also spoke Yiddish or Hebrew). All subjects had the capacity to provide informed consent and did so in writing after a complete description of the study.

Diagnostic assessments were made by trained clinicians/raters (J.A.G., R.G., A.E., and R.Y.) on the basis of structured interviews, the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (19) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (20). The PTSD group (N=31) consisted of survivors with current PTSD stemming from the trauma of the Holocaust. The no PTSD group (N=16) consisted of survivors without current or lifetime PTSD. Of the survivors with and without PTSD, 41% (N=13) and 44% (N=7), respectively, were recruited from the treatment program, which offers educational lectures and support groups as well as individual treatment. Persons with bipolar disorder, psychosis, substance abuse, or dementia were excluded from all groups. Persons with unipolar depression or anxiety disorders were excluded from the nonexposed group. Subjects with major medical or neurological illnesses (e.g., seizure disorder, stroke) or a history of significant head trauma were excluded. Subjects with other common illnesses (e.g., hypertension, hyperlipidemia, arthritis) were studied if medically stable.

Neuropsychological Testing

Explicit and implicit memory were assessed by using paired-associate recall and word stem completion, respectively (21), which have been used in studies of normal aging (6, 7).

For paired-associate recall, subjects were presented with 12 word pairs and asked to read them aloud and memorize them. The list was presented again in a different order. Subjects were asked to recall a member of the pair when presented with the other.

Since the nonassociative nature of the word pairs is generally the primary determinant of explicit memory deficits, the list consisted of six pairs of moderately related words (high associates) and six pairs of unrelated words (low associates). The related pairs corresponded to the third associate in free association norms to minimize guessing in the cued-recall task. The dependent variables were the mean numbers of high- and low-associate words correctly recalled. The related and unrelated pairs were matched in word frequency, word length, and grammatical category. Lupien and colleagues (6) previously verified the nonassociative nature of the unrelated words by asking 24 subjects to give the first word that came to mind when presented with one of the words from a pair. None of the words from the unrelated pairs generated the paired word.

Subjects were then given the word stem completion test, which was a distraction task used to conceal the connection between the explicit and implicit memory tests. Subjects were asked to complete 48 three-letter word stems (e.g., R _ _ _ E) as fast as possible using “the first word that comes to mind.” One-half of the stems corresponded to words presented in the paired-associate task; the remainder were randomly chosen. Implicit memory is inferred if the completed stems form stimulus words in the absence of explicit instructions to do so. The dependent variable was the percentage of target word stems completed with stimulus words. The combined vocabulary and block design scaled scores from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised (WAIS-R) (22) provided an approximation of IQ.

Statistical Method

Analysis of variance was used to evaluate group differences in age, education, current intelligence, and memory performance. Pairs of groups were compared by Tukey’s honestly significant difference if there was an overall significant group difference. Effect sizes (d) for the differences between pairs of means were calculated. Differences in gender, current depression, and medication use among groups were compared by Pearson chi-square. The associations of memory with age, current intelligence, and education were assessed by pooled within-group correlations. This was done by partial correlation, controlling for dummy-coded group membership variables. Fisher’s r-to-z transformation was used to evaluate whether within-group correlations differed between pairs of groups by using the asymptotic test based on the normal distribution. The associations of memory with gender, current depression, and medication were assessed by pooled within-group point biserial correlations after we controlled for group membership. We did not perform analyses of covariance to assess group differences in memory after differences in other measures, such as education, were controlled, since interpretation is problematic when the independent variable is preexisting groups rather than a random assignment to experimental conditions (23).

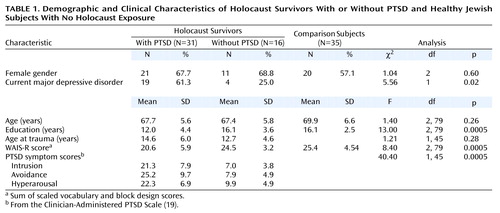

Results

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the three groups are shown in Table 1. There were 52 women (63%) and 30 men (37%), with a mean age of 68.6 years (SD=6.1, range=57–85). The groups were similar in age and gender distribution. They differed significantly in education level and in the WAIS-R scores (the sum of the scaled vocabulary and block design scores). This score provide an estimate of full-scale IQ; however, the age norms for estimated IQ from this score are only available as high as age 74. On the basis of these norms and using this upper age limit norm for the 13 subjects who were 75–85 years of age, the corresponding estimated IQs were 101.8 (SD=16.5) for the PTSD group, 112.9 (SD=9.2) for the no PTSD group, and 114.8 (SD=12.6) for the nonexposed group. The PTSD group had significantly lower WAIS-R scores than did the no PTSD group (p=0.004; d=0.83) and the nonexposed group (p<0.0005; d=0.91). The PTSD group had significantly fewer years of education than did the no PTSD group (p<0.0005; d=1.04) and the nonexposed group (p<0.0005; d=1.14). The no PTSD and nonexposed groups did not differ in years of education (p=0.998; d=0.02) or on WAIS-R scores (p<0.84; d=0.22). Among Holocaust survivors, those with PTSD were more likely than those without PTSD to meet criteria for major depressive disorder, and they scored significantly higher on the three PTSD symptom cluster scores. The PTSD and no PTSD groups did not differ in age at traumatization.

There was an overall group difference in psychotropic medication use: 19.4% (N=6) of the PTSD, 25.0% (N=4) of the no PTSD, and 2.9% (N=1) of the nonexposed subjects were receiving psychotropic medication (χ2=6.1, df=2, p<0.05). (The one nonexposed subject was receiving meprobamate as a muscle relaxant.) Medication types included antihypertensives (36.6% of the entire group [N=30 of 82]), lipid-lowering medication (14.6%, N=12), thyroid supplement (14.6%, N=12), estrogen-based hormone treatment (13.4%, N=11), gastrointestinal medication (12.2%, N=10), and medication for benign prostatic hypertrophy (2.4%, N=2). There were no significant group differences in the use of these medications (all χ2≤2.7 and p≥0.25).

The associations of gender, current major depressive disorder, and medication use with paired-associate recall performance were assessed (all df=78). Low-associate and high-associate recall were not significantly associated with gender (r=–0.01, p<0.90 and r=0.13, p<0.24, respectively), current major depressive disorder (r=0.02, p<0.83; r=0.14, p<0.22), or psychotropic medication (r=–0.06, p<0.63; r=–0.07, p<0.55). Although use of gastrointestinal medication was inversely associated with high-associate recall (r=–0.22, df=78, p<0.05), the groups did not differ in the use of this medication (χ2=0.88, df=2, p<0.65). None of the other classes of medication were associated with paired-associate recall at the p≤0.05 level.

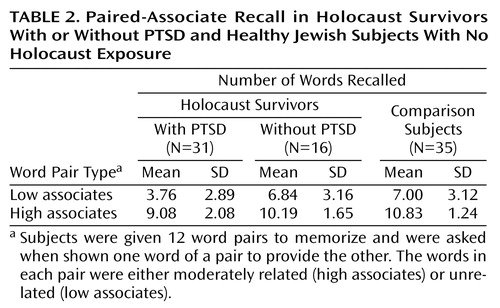

Paired-associate recall results are shown in Table 2. In the low-associate condition, there was an overall significant group difference (F=10.62, df=2, 79, p<0.0005). Analysis with Tukey’s honestly significant difference revealed that the PTSD group scored significantly lower than did the no PTSD group (p=0.004; d=1.02) and the nonexposed group (p<0.0005; d=1.08). The no PTSD and nonexposed groups did not differ (p<0.99; d=0.05). The mean recall in the PTSD group corresponded to a low (20th to 25th) percentile of the no PTSD and the nonexposed groups. Frank cognitive impairment was defined as a performance level at or below the fifth percentile of the comparison groups. With this criterion, 25.8% (N=8) of the PTSD group were impaired relative to the no PTSD group and 35.5% (N=11) were impaired relative to the nonexposed group.

There was a significant group difference in high-associate recall (F=8.97, df=2, 79, p<0.0005). Analysis with Tukey’s honestly significant difference revealed that the PTSD group scored significantly lower than did the nonexposed group (p<0.0005; d=1.02) and nonsignificantly lower than did the no PTSD group (p<0.09; d=0.59). The no PTSD and nonexposed groups did not differ (p<0.42; d=0.44). The mean number of high-associate words recalled by the PTSD group corresponded to the 25th to 30th percentile of the no PTSD group and the 10th to 15th percentile of the nonexposed groups. In relation to the no PTSD group, 12.9% (N=4) of the PTSD group were frankly impaired; 35.5% (N=11) of the PTSD subjects were frankly impaired in relation to the nonexposed group.

There was no significant group difference in word stem completion (F=2.08, df=2, 77, p<0.14).The mean rates of target word stem completion were 45.0% (SD=14.4%) in the PTSD group (N=29), 46.1% (SD=12.7%) in the no PTSD group (N=16), and 51.7% (SD=13.8%) in the nonexposed group (N=35).

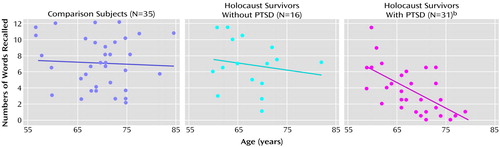

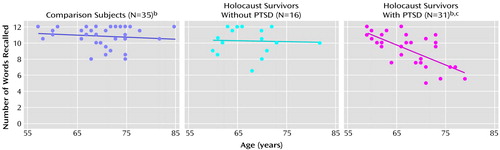

The correlations of memory performance with age, education, and intelligence are shown in Table 3. There was a substantial inverse association of both low-associate and high-associate recall, but not word stem completion, with age. Similarly, paired-associate recall, but not word stem completion, was significantly associated with education and estimated intelligence. The correlations between age and paired-associate recall performance are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. The association between age and low-associate recall was significant within the PTSD group but not within the no PTSD group (r=–0.19, df=14, p=0.490) or the nonexposed group (r=–0.09, df=33, p<0.62). The association in the PTSD group was significantly different from the nonexposed group (z=–2.56, p=0.01), and nonsignificantly differed from the no PTSD group (z=–1.68, p<0.10). The association between age and high-associate recall was substantial within the PTSD group but not within the no PTSD (r=–0.03, p<0.92) or the nonexposed group (r=–0.14, p=0.44). The association in the PTSD group was significantly different from both the nonexposed (z=–2.66, p=0.008) and no PTSD (z=–2.37, p<0.02) groups. The associations of IQ and education with paired-associate recall did not differ among the groups nor did the associations between age and word stem completion.

Discussion

Holocaust survivors with PTSD had poorer explicit memory than Holocaust survivors without PTSD or healthy Jewish subjects with no Holocaust exposure. The PTSD group scored significantly lower than both comparison groups on the more difficult low-associate recall condition. They performed less well than the nonexposed group on high-associate recall, which involves both semantic and explicit memory. On the basis of these measures, about one-third of the PTSD group performed at a level suggestive of frank cognitive impairment.

The finding of poorer explicit memory, but not implicit memory, in Holocaust survivors with PTSD is consistent with patterns described in lesions of the medial temporal lobe. Low-associate recall is an especially sensitive measure of hippocampal-dependent memory, requiring conscious effort and the formation of new semantic associations (6, 24, 25). Thus, the findings suggest there may be reduced hippocampal-dependent memory function in Holocaust survivors with PTSD. This is consistent with the finding of smaller hippocampal volumes in other populations with chronic PTSD (26–29). However, as the PTSD group also had less education and scored lower on intelligence tests, the poorer memory performance could reflect a more general pattern of lower cognitive functioning.

The performance differences between the Holocaust survivors with PTSD and those without PTSD are particularly noteworthy, since the groups are similar in many ways. All subjects were exposed to massive psychological trauma during the Holocaust and profound loss and chronic stress in its aftermath. Additionally, as European immigrants, they had similar linguistic backgrounds. Although depression was prevalent among survivors, it did not account for the performance differences. Poor explicit memory has been found in major depression in other studies (30, 31) but not in this one. This difference likely reflects that major depressive disorder occurred mainly as a comorbid disorder; as such, a diagnosis of depression may reflect symptom overlap or may be indicative of a secondary manifestation of PTSD rather than a primary affective disorder.

It is not known when these performance differences would have first been apparent. Since the PTSD survivors had fewer years of education and lower intelligence scores, it may be that differences would have been apparent before trauma exposure and that higher levels of education or better cognitive functioning were protective factors that helped some survivors recover from the trauma of the Holocaust. Indeed, there is evidence in other populations that less education or lower intelligence may be vulnerability factors that increase the risk of PTSD (32, 33). It should be noted, however, that the PTSD group was of average intelligence and by no means uneducated; it is not known if differences within this range of intelligence and education are associated with differences in the risk for PTSD. In the literature on normal aging, for example, while lower education is a risk factor for age-related memory decline, education beyond 9 years does not appear to confer additional protection (4).

Then again, some survivors were able to continue their education after the disruption of the Holocaust. Furthermore, current performance on the WAIS-R may be adversely affected by PTSD and may not reflect premorbid intelligence. Thus, lower educational attainment and performance on intelligence tests, as well as poorer explicit memory performance, may be sequelae of PTSD. The memory differences could have developed in tandem with PTSD or as a consequence of an interaction of chronic PTSD and aging. Aging is associated with hippocampal atrophy and poor explicit memory, and stress appears to accelerate memory decline (4, 6, 7, 18). Thus, the differential association of recall and age in the present study raises the possibility that there is an interactive effect of age and PTSD on memory function in Holocaust survivors. These findings are consistent with the possibility of accelerated memory decline in Holocaust survivors with PTSD and with observations of premature aging in the Concentration Camp Syndrome (1). However, such a possibility could only be conclusively demonstrated in a longitudinal study.

There are other possible explanations for the differential association between age and recall in this cross-sectional study. Survivors were all exposed to massive trauma during a discrete period in history. Their current age is highly correlated with age at exposure, making it difficult to disentangle these effects. Therefore, the findings could also reflect a differential effect of age at trauma exposure and PTSD on neurodevelopment. However, the literature on traumatic brain injury suggests the developing brain may be more susceptible to insults than the mature brain. For example, following traumatic brain injury, young children are more likely than older ones to have enduring neuropsychological deficits (34, 35). Only when traumatic brain injuries occur in senescence is there a positive association between age and posttraumatic deficits (36). Thus, if the effects of age at Holocaust trauma parallel those of physical trauma, they would not readily explain the age relationships found. Other trauma-related factors may have also influenced performance and its relationship with age. Physical trauma, disease, and malnutrition accompanied the psychological trauma of the Holocaust. Subjects with head trauma were excluded, but the remaining factors are difficult to quantify retrospectively and were too prevalent to serve as exclusionary factors but may have varied by age of exposure and diagnostic group and contributed to group differences.

English was not the native language for survivors, raising the question of whether linguistic differences explain the PTSD group’s poorer performance. Verbal tests are generally performed better in one’s native language, especially those that require speed (e.g., verbal fluency); however, the effects appear less pronounced on memory tests (37–39). For example, proficient Spanish-English bilinguals did not differ from monolinguals in recall or retention (39). Subjects proficient in French and English had higher recall in both languages than monolinguals (40). So it is unclear how differences in linguistic background might affect performance in these multilingual subjects proficient in English. Indeed, the pattern of differences found suggests such linguistic differences did not substantially account for the findings. Low-associate recall differed considerably between the Holocaust survivors with PTSD and those without PTSD, who have similar backgrounds. A similar magnitude of difference was seen between the PTSD and nonexposed groups, who have dissimilar linguistic backgrounds. Similarly, the no PTSD and nonexposed groups did not differ, suggesting the nonnative use of English did not appreciably affect performance.

The results are consistent with those studies which have found poorer memory performance in PTSD (8–11). The neuropsychological findings in PTSD have been inconsistent (12–14), even within rather homogeneous populations. The findings have been inconsistent in PTSD, even within rather homogenous populations. Studies comparing Vietnam veterans with PTSD to noncombat comparison subjects have found no differences in memory (12), circumscribed differences in serial learning (9), and diffuse impairments in verbal and visual memory (8). Yet, when combat veterans with and without PTSD were compared, no differences were found in memory performance, including verbal paired associates (13). A substantial proportion of PTSD subjects in the aforementioned studies had a history of substance abuse, also associated with memory deficits (41), which may have contributed to the inconsistencies. Thus, the present study adds to this literature in finding poorer explicit memory in PTSD subjects than similarly exposed comparison subjects that could not be explained by depression or substance abuse.

If there is a different relationship between aging and cognitive functioning in PTSD, this might also explain some of the inconsistencies in the literature. There are no measures of memory that can be compared across existing studies of PTSD, but the Trail Making Test, an attentional measure sensitive to age, has been used in three studies of treatment-seeking Vietnam veterans with PTSD. The mean ages of the study groups were 37 (12), 43 (13), and 49 (42) years. With increasing age of the subjects studied, the PTSD-associated abnormalities became more apparent, and there was a corresponding increase in the mean time to complete part B (70, 83, and 101 seconds). This is consistent with the possibility that cognition is sensitive to age in PTSD even in domains that are not dependent on the hippocampus.

In summary, these findings demonstrate that there are considerable differences in explicit memory performance in Holocaust survivors with PTSD and that cognitive impairment may be an associated feature of this disorder in a subset of older survivors. Replication is needed in other populations, especially in those who sustained less severe psychological and physical trauma, in order to determine whether the findings are broadly applicable to PTSD. Longitudinal studies are also needed to clarify the significance of the apparent relationship between age and performance in PTSD. It has become increasingly clear that PTSD is a prevalent, chronic disorder associated with considerable functional impairment. Should PTSD be associated with accelerated cognitive decline, it would further increase the burden of this illness with aging.

|

|

|

Received Feb. 20, 2001; revisions received Aug. 20, 2001, and March 11, 2002; accepted March 19, 2002. From the Department of Psychiatry, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York; the Department of Psychiatry, Bronx Veterans Affairs Medical Center; and the Douglas Hospital Research Center of McGill University, Verdun, Quebec. Address reprint requests to Dr. Golier, Department of Psychiatry (116A), Bronx VAMC, 130 West Kingsbridge Rd., Bronx, NY 10468; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grant MH-49555 to Dr. Yehuda. The authors thank James Schmeidler, Ph.D., for assistance with statistical analyses and reviews of the manuscript.

Figure 1. Relationship Between Age and Low-Associate Recalla in Holocaust Survivors With or Without PTSD and Healthy Jewish Subjects With No Holocaust Exposure

aSubjects were given six word pairs to memorize and were asked when shown one word of a pair to provide the other. The words in each pair were unrelated (low associates).

bSignificant inverse association between low-associate recall and age (r=–0.64, df=29, p<0.0005). Some data points missing because of overlap.

Figure 2. Relationship Between Age and High-Associate Recalla in Holocaust Survivors With or Without PTSD and Healthy Jewish Subjects With No Holocaust Exposure

aSubjects were given six word pairs to memorize and were asked when shown one word of a pair to provide the other. The words in each pair were moderately related (high associates).

bSome data points missing because of overlap.

cSignificant inverse association between high-associate recall and age (r=–0.68, df=29, p<0.005).

1. Eitinger L: The concentration camp syndrome: an organic brain syndrome. Integr Psychiatry 1985; 3:115-126Google Scholar

2. Kuch K, Cox BJ: Symptoms of PTSD in 124 survivors of the Holocaust. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:337-340Link, Google Scholar

3. Yehuda R, Elkin A, Binder-Brynes K, Kahana B, Southwick SM, Schmeidler J, Giller EL Jr: Dissociation in aging Holocaust survivors. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:935-940Link, Google Scholar

4. Lyketsos CG, Chen L-S, Anthony JC: Cognitive decline in adulthood: an 11.5-year follow-up of the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:58-65Link, Google Scholar

5. Sapolsky RM, Krey LC, McEwen BS: The neuroendocrinology of stress and aging: the glucocorticoid cascade hypothesis. Endocr Rev 1986; 7:284-301Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Lupien S, Lecours AR, Lussier I, Schwartz G, Nair NP, Meaney MJ: Basal cortisol levels and cognitive deficits in human aging. J Neurosci 1994; 14:2893-2903Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Lupien SJ, de Leon M, de Santi S, Convit A, Tarshish C, Nair NP, Thakur M, McEwen BS, Hauger RL, Meaney MJ: Cortisol levels during human aging predict hippocampal atrophy and memory deficits. Nat Neurosci 1998; 1:69-73Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Bremner JD, Scott TM, Delaney RC, Southwick SM, Mason JW, Johnson DR, Innis RB, McCarthy G, Charney DS: Deficits in short-term memory in posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1015-1019Link, Google Scholar

9. Yehuda R, Keefe RSE, Harvey PD, Levengood RA, Gerber DK, Geni J, Siever LJ: Learning and memory in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:137-139Link, Google Scholar

10. Vasterling JJ, Brailey K, Constans JI, Sutker PB: Attention and memory dysfunction in posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychology 1998; 12:125-133Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Jenkins MA, Langlais PJ, Delis D, Cohen R: Learning and memory in rape victims with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:278-279Abstract, Google Scholar

12. Dalton JE, Pederson SL, Blom BE, Besyner JK: Neuropsychological screening for Vietnam veterans with PTSD. VA Practitioner 1986; 3:37-47Google Scholar

13. Gurvits TV, Lasko NB, Schachter SC, Kuhne AA, Orr SP, Pitman RK: Neurological status of Vietnam veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1993; 5:183-188Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Stein MB, Hanna C, Vaerum V, Koverola C: Memory functioning in adult women traumatized by childhood sexual abuse. J Trauma Stress 1999; 12:527-534Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Graf P, Schacter DL: Implicit and explicit memory for new associations in normal and amnesic subjects. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 1985; 11:501-518Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Squire LR: Memory and the hippocampus: a synthesis from findings with rats, monkeys, and humans. Psychol Rev 1992; 88:195-231Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Light LL, Singh A: Implicit and explicit memory in young and older adults. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 1987; 4:531-541Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Golomb J, de Leon M, Kluger A, George AE, Tarshish C, Ferris SH: Hippocampal atrophy in normal aging: an association with recent memory impairment. Arch Neurol 1993; 50:967-973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, Keane TM: The development of a Clinician Administered PTSD Scale. J Trauma Stress 1995; 8:75-90Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1997Google Scholar

21. Lussier I, Peretz I, Belleville S, Fonatine F: Contributions of indirect measures of memory to clinical neuropsychology assessments. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1989; 11:64Google Scholar

22. Wechsler D: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised. New York, Psychological Corp, 1981Google Scholar

23. Miller GA, Chapman JP: Misunderstanding analysis of covariance. J Abnorm Psychol 2001; 110:40-48Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Henke K, Weber B, Kneifle S, Wieser HG, Buck A: Human hippocampus associates information in memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999; 96:5884-5889Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. des Rosiers G, Ivinson S: Paired associate learning: normative data for differences between high and low associate word pairs. J Clin Exp Neuropsychology 1986; 8:637-642Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Bremner JD, Randall P, Scott TM, Bronen RA, Seibyl JP, Southwick SM, Delaney RC, McCarthy G, Charney DS, Innis RB: MRI-based measurement of hippocampal volume in patients with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:973-981Link, Google Scholar

27. Bremner JD, Randall P, Vermetten E, Staib L, Bronen RA, Mazure C, Capelli S, McCarthy G, Innis RB, Charney DS: Magnetic resonance imaging-based measurement of hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood physical and sexual abuse—a preliminary report. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 41:23-32Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Stein MB, Koverola C, Hanna C, Torchia MG, McClarty B: Hippocampal volume in women victimized by childhood sexual abuse. Psychol Med 1997; 27:951-959Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Gurvits TV, Shenton ME, Hokama H, Ohta H, Lasko NB, Gilbertson MW, Orr SP, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA, McCarley RW, Pitman RK: Magnetic resonance imaging study of hippocampal volume in chronic, combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 40:1091-1099Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Danion JM, Willard-Schroeder D, Zimmermann MA, Grange D, Schlienger JL, Singer L: Explicit memory and repetition priming in depression: preliminary findings. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:707-711Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Bazin N, Perruchet P, De Bonis M, Feline A: The dissociation of explicit and implicit memory in depressed patients. Psychol Med 1994; 24:239-245Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Pitman RK, Orr SP, Lowenhagen MJ, Macklin ML, Altman B: Pre-Vietnam contents of PTSD veterans’ service medical and personnel records. Compr Psychiatry 1991:416-422Google Scholar

33. Macklin ML, Metzger LJ, Litz BT, McNally RJ, Lasko NB, Orr SP, Pitman RK: Lower precombat intelligence is a risk factor for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998; 66:323-326Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Anderson VA, Morse SA, Klug G, Catroppa C, Haritou F, Rosenfeld J, Pentland L: Predicting recovery from head injury in young children: a prospective analysis. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 1997; 3:568-580Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Verger K, Junque C, Jurado MA, Tresserras P, Bartumeus F, Nogues P, Poch JM: Age effects on long-term neuropsychological outcome in paediatric traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 2000; 146:495-503Google Scholar

36. Rothweiler B, Temkin NR, Dikmen SS: Aging effect on psychosocial outcome in traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 8:881-887Crossref, Google Scholar

37. Ardila A, Rosselli M, Ostrosky-Solis F, Marcos J, Granda G, Soto M: Syntactic comprehension, verbal memory, and calculation abilities in Spanish-English bilinguals. Appl Neuropsychol 2000; 7:3-16Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Rosselli M, Ardila A, Araujo K, Weekes VA, Caracciolo V, Padilla M, Ostrosky-Soulis F: Verbal fluency and repetition skills in healthy older Spanish-English bilinguals. Appl Neuropsychol 2000; 7:17-24Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Harris JG, Cullum C, Puente AE: Effects of bilingualism on verbal learning and memory in Hispanic adults. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 1995; 1:10-16Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Nott CR, Lambert WE: Free recall of bilinguals. J Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior 1965; 7:1065-1071Crossref, Google Scholar

41. Svanum S, Schladenhauffen J: Lifetime alcohol consumption among male alcoholics: neuropsychological implications. J Nerv Ment Dis 1986; 174:214-220Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Beckham JC, Crawford AL, Feldman ME: Trail Making Test performance in Vietnam combat veterans with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress 1998; 11:811-819Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar