Cycling Into Depression From a First Episode of Mania: A Case-Comparison Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The characteristics of patients who cycle from mania to major depression and the frequencies of these cycles remain poorly understood. METHOD: This study compared 28 patients with a first episode of mania who cycled into a major depressive episode without recovery from their index episode and 148 patients with first-episode mania who did not cycle into depression. Patients were given extensive assessments at baseline and 6-, 12-, and 24-month follow-ups. Comparisons between the two groups were made on demographic variables, clinical ratings, and outcome variables. RESULTS: Approximately 16% of the patients with a first episode of mania cycled into major depression. Patients who cycled into depression were more likely to have higher depressive scores at admission and tended to have the mixed subtype of bipolar disorder. CONCLUSIONS: Patients with first-episode mania who score high for depression at admission may be at greater risk of cycling into a major depressive episode.

The course of manic-depressive illness is usually one of multiple recurrences. Few studies have examined the characteristics of patients with bipolar disorder who cycle from mania into a major depressive episode. It has been reported that between 15% and 58% of patients will cycle into depression before meeting recovery criteria from their manic episode (1–5). Winokur and colleagues (1) stressed that “the psychiatrist must be prepared to treat both poles of the illness during each episode” (p. 85). The differences in the rates of cycling during the index episode reported in various studies may result from the chronic effects of pharmacological treatment and illness. Knowing what factors predict cycling into depression may have important implications for treatment and outcome. Clinicians may be tempted to treat a major depressive episode with an antidepressant that perhaps may negatively influence the course of illness by inducing rapid cycling or switching into mania.

A cohort with a first episode of mania systematically and prospectively studied is perhaps well suited to disentangle some of these confounding factors. The objectives of the present study were 1) to determine the prevalence of a first episode of mania in patients who cycled into a major depressive episode from their index episode, 2) to identify demographic and clinical characteristics predictive of cycling in such a population, and 3) to determine whether cycling into a major depressive episode was predictive of outcome.

Method

Subjects were drawn from the McLean-Harvard First-Episode Mania Study, the methods of which have been described in detail elsewhere (6). Briefly, the study group consisted of patients with a first episode of mania who had been consecutively admitted to inpatient units. Eligible patients met DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I disorder, current episode manic or mixed; the diagnosis was obtained by use of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Version (SCID-P) (7). The subjects were at least 18 years old, and they provided written informed consent. The patients with evidence of organic mood syndrome, dementia, or an IQ of 70 or less were excluded. All treatment was determined clinically and was not controlled by the investigators.

The patients were given an extensive initial evaluation and weekly assessments during their hospitalizations, including the expanded, 36-item McLean version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (8), the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (9), and the Clinical Global Impression severity of illness scale (10). The patients were also evaluated at 6-, 12-, and 24-month follow-ups by the study interviewers to assess syndromic and functional recovery. The definitions of recovery were operationally defined and have been described elsewhere (6). Also, to assess the stability of the patients’ diagnoses, a SCID diagnosis was obtained at 24-month follow-up by a professional who was blind to the baseline SCID diagnosis.

Comparisons between patients who did and did not cycle into a major depressive episode were made on demographic characteristics, total BPRS and Hamilton depression scale scores at admission, and syndromic and functional outcomes. “Cycling into depression” was defined as occurring when patients developed a DSM-IV major depressive episode immediately after their manic episode without first achieving syndromic recovery (defined as 8 weeks of euthymia). The patients who did not meet these criteria were classified as “not cycling into depression.”

Categorical variables were compared by use of Fisher’s exact test. Nonparametric means were compared by use of the Mann-Whitney U test. The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05. All tests were two-tailed.

Results

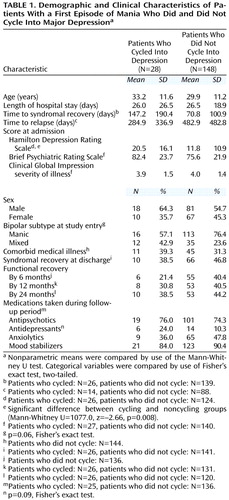

Twenty-eight (15.9%) of 176 patients with a first episode of mania cycled into a major depressive episode (Table 1). There were no differences between the groups that did (N=28) and did not (N=148) cycle into depression in age, sex, length of hospital stay, time to syndromal recovery, time to relapse, comorbid medical illnesses, and total BPRS scores at admission. Similarly, there were no differences between the groups in the proportion of patients meeting syndromal recovery criteria at discharge or functional recovery criteria at follow-up or in the use of psychotropic medications during the follow-up period. The patients who cycled into depression, compared to those who did not, were more likely to have higher Hamilton depression scale total scores at admission (mean=20.5, SD=16.1, versus mean=11.8, SD=10.9) (Mann-Whitney U=1077.0, z=–2.66, N=150, p=0.008). There was a greater likelihood for the patients who cycled into depression to have the mixed versus manic subtype of episode at study entry (12 of 28, 42.9%, versus 35 of 148, 23.6%) (p=0.06, Fisher’s exact test).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study that systematically and prospectively evaluated the risk factors for cycling into depression in a group of patients with a first episode of mania. Approximately 16% of our patients cycled into major depression. This figure is similar to the percentage of 15% in another study (4) but lower than the 20%–58% reported by other investigators (1–3, 5). The finding in the present study that a higher Hamilton depression scale total score at admission was associated with a greater risk of cycling into depression has not been previously reported, to our knowledge. We did not find that the presence of cycling in the index episode was associated with a worse long-term outcome or a significantly greater use of antidepressants. The lack of association between cycling into depression and outcome has been previously reported (4). However, another study (3) did find that cycling was associated with poor outcome. It is possible that differences in methodologies used among the different studies and small size of the group that cycled into depression in our study precluded us from finding these differences. However, contrary to our methods, combined mixed and cycling groups were used in the outcome analysis by Keller and colleagues (5). This study found that cycling after a first episode of mania is fairly uncommon and that the long-term outcome does not appear to be significantly affected by course of the initial episode.

|

Received April 5, 2000; revisions received Nov. 1, 2000, and March 15, 2001; accepted March 22, 2001. From the Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program, National Institute of Mental Health; McLean Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Belmont, Mass.; Lilly Research Laboratories, Indianapolis; and the Behavioral Science Research Core, University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worcester, Mass. Address reprint requests to Dr. Zarate, Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program, National Institute of Mental Health, 9000 Rockville Pike, Bldg. 10, Unit 3 West, Rm. 3s250, Bethesda, MD 20892; [email protected] (e-mail). Funded in part by a National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression Young Investigator Award (Dr. Zarate).

1. Winokur G, Clayton PJ, Reich T: Manic Depressive Illness. St Louis, CV Mosby, 1969Google Scholar

2. Angst J: Switch from depression to mania, or from mania to depression: role of psychotropic drugs. Psychopharmacol Bull 1987; 23:66-67Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kukopulos A, Reginaldi D, Laddomada P, Floris G, Serra G, Tondo L: Course of the manic-depressive cycle and changes caused by treatments. Pharmakopsychiatr Neuropsychopharmakol 1980; 13:156-167Medline, Google Scholar

4. Tohen M, Waternaux CM, Tsuang MT: A 4-year prospective follow-up of 75 patients utilizing survival analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:1106-1111Google Scholar

5. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Coryell W, Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Clayton PJ, Klerman GL, Hirschfeld RM: Differential outcome of pure manic, mixed/cycling, and pure depressive episodes in patients with bipolar illness. JAMA 1986; 255:3138-3142Google Scholar

6. Tohen M, Hennen J, Zarate CM Jr, Baldessarini RJ, Strakowski SM, Stoll AL, Faedda GL, Suppes T, Gebre-Medhin P, Cohen BM: Two-year syndromal and functional recovery in 219 cases of first-episode major affective disorder with psychotic features. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:220-228Link, Google Scholar

7. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Version (SCID-P). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1988Google Scholar

8. Lukoff D, Neuchterlein KH, Ventura J: Manual for the expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Schizophr Bull 1986; 12:594-602Google Scholar

9. Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967; 6:278-296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Guy W, Bonato R (eds): Manual for the ECDEU Assessment Battery, 2nd ed. Chevy Chase, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1970, pp 12-1-12-6Google Scholar