Symptom Reduction and Suicide Risk Among Patients Treated With Placebo in Antipsychotic Clinical Trials: An Analysis of the Food and Drug Administration Database

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The assumption that psychotic patients assigned to placebo in clinical trials of antipsychotics are exposed to substantial morbidity and mortality is not based on data about what actually happens to such patients. This study assesses symptoms and risks of suicide and suicide attempts in psychotic patients assigned to receive placebo in clinical trials. METHOD: The authors used the Food and Drug Administration database to assess suicides, suicide attempts, and psychotic symptom reduction in clinical trials of three new antipsychotics. RESULTS: Among 10,118 participating patients, 26 committed suicide and 51 attempted suicide. Rates of suicide and attempted suicide did not differ significantly between the placebo-treated and the drug-treated groups. Annual rates of suicide and attempted suicide based on patient exposure years were 1.8% and 3.3%, respectively, with placebo; 0.9% and 5.7% with an established antipsychotic; and 0.7% and 5.0% with a new antipsychotic. Symptom reduction was 16.6% with new antipsychotics (N=1,203), 17.3% with established antipsychotics (N=261), and 1.1% with placebo (N=462). CONCLUSIONS: These data may help inform discussions about the use of placebo in antipsychotic clinical trials.

Recent years have seen intense scrutiny of clinical research involving psychotic patients, particularly those with schizophrenia (1, 2). The risks of symptom provocation, drug withdrawal, and placebo treatment continue to be debated. The concerns about these research strategies, and the new research regulations and consent requirements arising from these concerns, are based on few or no empirical data. The supposed risks of placebo treatment are a case in point.

During the past half-century, the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial has become the gold standard for treatment evaluation. In the United States, many scientific investigators and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) widely regard placebo controls as necessary to establish the efficacy of a putative treatment. Nonetheless, in recent years the scientific community, the federal government, and the popular press have questioned the scientific and ethical grounds for placebo controls.

Placebo treatment of psychotic patients involves several potential risks. Among them are the distress and disruption produced by the continuation of psychotic symptoms and, most ominous, the risk of suicide. The actual risk of suicide in psychotic patients treated with placebo, however, is unknown. Information about suicide risk is required for a rational risk-benefit analysis of placebo-controlled clinical trials. Such information could usefully inform investigators, potential subjects, and their families.

To address this issue, we examined the FDA database for the four antipsychotics approved between 1987 and 1997: clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine fumarate. We determined the incidence of suicide and suicide attempts for patients participating in these antipsychotic clinical trials. We then examined the data from pivotal studies (those deemed well designed and well controlled) to assess comparative symptom reduction among patients who were assigned to antipsychotic and placebo treatments. Clozapine was not included in this analysis because those trials did not contain placebo controls.

The FDA database on investigational medications is uniquely suited for providing relatively unbiased data on the fate of psychotic patients who are assigned to placebo. First, the FDA requires full disclosure of all data from all studies conducted worldwide for a drug under development. Second, the FDA determines whether a new antipsychotic is efficacious on the basis of studies deemed well designed and well controlled (i.e., pivotal) under Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations (3). For antipsychotics, these pivotal studies by convention and practice are randomized, double-blind, and placebo controlled and include established criteria for the sample under study as well as defined criteria for response. The data from these studies must be sufficient to assess effects according to specific methods of analysis. Typically, these are phase II and phase III studies with several hundred patients. Third, studies are designated as pivotal without regard to outcome; many pivotal studies do not demonstrate statistical superiority of antipsychotics over placebo.

We used the entire FDA database for the three antipsychotics (N=10,118) for assessing frequency of suicide and suicide attempts, and we used FDA data from seven selected pivotal studies (N=1,926) for efficacy analysis. These two databases are summarized and reported separately by the FDA staff.

Method

We obtained FDA clinical trial data for four antipsychotics approved in the United States during the 6-year study period. Specifically, under the Freedom of Information Act (4), we obtained public domain data on FDA-reviewed studies for clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine fumarate by a specific request to the FDA (Freedom of Information Staff, 5600 Fishers Lane, HFI-35 Rockville, MD 20857). The data were sent on microfiche for a small fee. Since the clozapine FDA data did not contain any placebo-controlled studies for review of suicide risk or symptom reduction, we did not used these data for our analysis.

To assess safety, we reviewed the available clinical data for incidence of suicides and suicide attempts. These data encompassed all worldwide clinical trial data obtained during the drugs’ development (Table 1), including both pivotal and nonpivotal studies. We were able to estimate the incidence of suicide and suicide attempts on the basis of patient exposure years (i.e., cumulative time that subjects were exposed to a new antipsychotic, an established antipsychotic, or placebo while in a research program).

Chi-square analysis was used to assess the statistical significance of differences in the frequency of suicide and suicide attempts among those taking placebo, new antipsychotics, and established antipsychotics.

To access efficacy, we used the data from clinical trials reviewed by the FDA in support of a drug’s indication. From the research programs of the three antipsychotics, the FDA considered 10 studies to be pivotal; of these, three were excluded from our analysis because they did not include a placebo control (Table 2). The seven studies we included are risperidone 201 and 204, olanzapine HGAD and HGAP, and quetiapine fumarate 0006, 0008, and 0013.

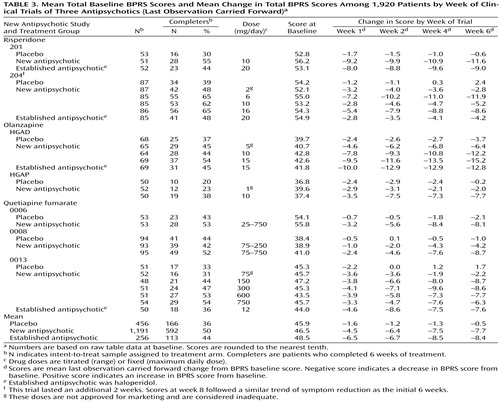

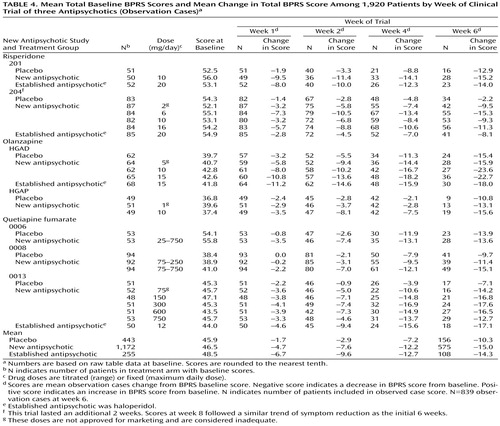

The available symptom intensity scores were the mean total Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (5) scores at double-blind random assignment to drug or placebo (baseline); the mean total BPRS scores of the last observation carried forward at 1, 2, 4, and 6 weeks of treatment; and the mean total BPRS scores at observation cases at 1, 2, 4, and 6 weeks of treatment. We first used the last observation carried forward technique, in which patients prematurely terminating from the trial are assumed to experience no further improvement; thus, the last measured BPRS scores are considered the final (or end-of-trial) scores to assess symptom reduction. Because of a high rate of trial discontinuation (54% of those assigned to antipsychotics and 66% for those assigned to placebo), we also used the observation cases technique. In observation cases analysis, only the BPRS scores of patients still participating in the study are included. We used the mean total scores on the intent-to-treat population, defined as those having at least one dose of double-blind medication and at least one efficacy rating during the double-blind phase.

Because none of the available FDA reports included the standard error of the mean or standard deviation for the mean change in total BPRS score from baseline to last observation carried forward or observation cases, we were unable to calculate the effect size.

Of the seven studies analyzed (Table 2), three were two-armed (study drug versus placebo), and four were three-armed (study drug versus established antipsychotic [haloperidol] and placebo). Study duration was 6 weeks for six studies and 8 weeks for one study.

Each of the studies used the following standard subject inclusion and exclusion criteria: 1) 18 years of age or older; 2) met DSM-III or DSM-III-R criteria for schizophrenia; 3) signed informed consent form (witnessed); 4) minimum score at screen evaluation of at least 30 on the BPRS; 5) 4 to 10 days of placebo run-in; 6) not actively suicidal or posing a serious suicidal risk; and 7) no significant concurrent or previous other psychiatric illnesses.

Each study has the following design features: 1) primary efficacy measures included the BPRS; 2) mean total raw scores and change in scores on the BPRS were available for calculations and comparisons; 3) psychotic patients underwent evaluation at weekly intervals during the first month and at least biweekly after 4 weeks; and 4) the dose of the antipsychotics was adequate based on standard practice. (Four of the 18 treatment arms had doses lower than those approved for marketing [Table 3 and Table 4].)

Results

Table 1 describes the incidence of suicides and suicide attempts for the 10,118 patients participating in clinical trials evaluating the three antipsychotics. Twenty-six patients committed suicide, 22 while receiving a new antipsychotic, three while receiving an established antipsychotic, and one while receiving placebo. Overall incidence of suicide based on patient exposure years was 752/100,000 per year (26/3455.8). Among patients receiving an established antipsychotic, incidence of suicide was 950/100,000 per year (3/315.7); among patients receiving a new antipsychotic, 713/100,000 per year (22/3083.4); and among patients receiving placebo, 1,763/100,000 per year (1/56.7). The differences in suicide did not approach statistical significance (χ2=0.99, df=2, p=0.6).

A total of 51 patients attempted suicide, 43 while receiving a new antipsychotic, seven while receiving an established antipsychotic, and one while receiving placebo. The overall risk was 5,048/100,000 per year (51/1011); among patients receiving new antipsychotic, the risk was 5,011/100,000 per year (43/858); among patients receiving the established antipsychotic, the risk was 5,704/100,000 per year (7/122.7); and among patients receiving placebo the risk was 3,378/100,000 per year (1/29.6). The differences in rates of suicide attempts did not approach statistical significance (χ2=0.21, df=2, p=0.7).

Table 2 describes the seven pivotal studies of the three antipsychotics. A total of 1,926 patients participated in these studies; 1,203 (62.5%) received a new antipsychotic; 261 (13.6%) received an established antipsychotic; and 462 (24.0%) received placebo.

Table 3 shows the mean baseline total BPRS scores and mean change in total BPRS for weeks 1, 2, 4, and 6 using the last observation carried forward. Among the 1,203 patients receiving a new antipsychotic, the mean decrease in total BPRS score at last observation carried forward (week 6) was 16.6%; among the 261 patients receiving an established antipsychotic, 17.3%; and among the 462 patients receiving placebo, 1.1%.

Table 4 shows the mean baseline total BPRS scores and the mean change in total BPRS for weeks 1, 2, 4, and 6 using observation cases. For the 839 patients considered (observation cases at week 6), the mean decrease in total BPRS was 32.3% among the 575 patients continuing a new antipsychotic; 29.5% among the 108 patients continuing an established antipsychotic; and 22.4% among the 156 patients continuing the placebo.

The patient study completion rates (Table 3) favored a new antipsychotic. In the seven studies, six favored a new antipsychotic and one favored an established antipsychotic.

Discussion

Our aim was to assess the fate of psychotic patients who were assigned to placebo treatment in antipsychotic clinical trials. Specifically, we assessed risks for suicide and suicide attempt and the magnitude of change in BPRS scores for patients who were randomly assigned to either placebo or antipsychotic drug.

Overall incidence of suicide and attempted suicide was 752/100,000 per year and 5,048/100,000 per year, respectively. The differences in rates of suicide and attempted suicide among new antipsychotics, established antipsychotics, and placebo (Table 1>) did not approach statistical significance.

The annual suicide rate for the general population of the United States is approximately 11/100,000 per year (6). We found that the annual suicide rate of patients participating in antipsychotic clinical trials was almost 70 times higher than that in the general population. The suicide rate we found is higher than some published estimates of the annual suicide rate among patients with schizophrenia, which is 5–50 times higher than that of the general population (7, 8). Furthermore, is has been reported that 20%–40% of all patients with schizophrenia will attempt suicide in their lifetimes (8). Approximately 5% of the patients in our sample of clinical trials attempted suicide in a year’s time, an extraordinarily high rate. The suicide and suicide attempt rates in these patients is similar to that of patients participating in antidepressant clinical trials (9, 10).

Clozapine reportedly reduces suicide risk among psychotic patients by 80%–85% (11). Currently underway is the International Clozaril/Leponex Suicide Prevention Trial (11), testing the hypothesis that clozapine therapy can reduce suicide risk. These data should be available in 2001. In the FDA database, we noted two suicides among 1,080 patients exposed to clozapine during clinical trials. These clozapine trials did not include a placebo group, and the FDA report did not include data on suicide risk rate among patients treated with established antipsychotics such as chlorpromazine and haloperidol.

It should be noted that the studies of risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine fumarate that we reviewed were not designed to assess whether these antipsychotics could reduce suicidality. In fact, several factors limit the interpretation of the suicide risk data among these studies. Exposure time was not similar for the patients assigned to placebo or typical or atypical antipsychotics. Since many studies include a lengthy open-label safety study after the acute (double-blind, placebo-controlled) trial is over and because the acute trial is customarily among inpatients but the safety study is among outpatients, use of long-term outpatient data should not be confused with inpatient data. It is much easier to commit suicide as an outpatient. Thus, the most admissible finding in this report is that there was only one suicide in the placebo groups during the development phase of three antipsychotics.

Regarding efficacy based on last observation carried forward analysis, placebo-treated patients had almost no reduction in symptoms according to mean total BPRS scores. Patients treated with a new antipsychotic or an established antipsychotic experienced about a 17% reduction in mean total BPRS scores. Since the dropout rate for patients in the antipsychotic trials was so high (54% for patients assigned to an antipsychotic and 67% for those assigned to placebo), we used the observation cases technique for assessing outcome in addition to last observation carried forward analysis.

It is interesting to note that the magnitude of the difference between antipsychotics and placebo in reduction of symptoms according to mean total BPRS score was smaller with the observation cases technique than with the last observation carried forward method of analysis. Perhaps patients who respond nonspecifically to antipsychotics or placebo or patients who have a better prognosis and likelihood of better response may be overrepresented among those completing the trial. These finding raise questions about the validity and utility of placebo in antipsychotic clinical trials.

Shamoo and Irving (1) pointed out that many patients who prematurely discontinue a study have no aftercare and have a high risk for relapse. This is a factor to be kept in mind when conducting antipsychotic clinical trials. Specifically, criteria for aftercare among these patients should be established at the time of consent. Thus, three factors—suicide risk, magnitude of difference between antipsychotics and placebo in symptom reduction, and high dropout rates—need to be considered in the design and execution of future antipsychotic clinical trials.

Clinical trials for evaluating new antipsychotics are not primarily designed to identify the optimal effect of antipsychotics but, rather, to assess their efficacy rapidly. Therefore, dose, duration, and diagnosis in clinical trials are not necessarily ideally suited to identify the optimal effects of antipsychotics. Accordingly, clinical trials may identify only the lower bound of the effect size. The studies’ inclusion and exclusion criteria select groups of psychotic patients who are not representative of those seen in clinical practice.

Several features of the FDA database limit our conclusions. We were unable to calculate specific response rates to drug versus placebo, to establish acceptable confidence intervals between drug and placebo, or to establish effects on patients who terminated the clinical trials prematurely. However, degree of symptom reduction is a valid method to assess outcome in acute treatment clinical trials and is routinely used in reporting results in antipsychotic clinical trials.

In conclusion, the risk for suicide and suicide attempts is high among psychotic patients and is similar among those assigned to placebo and those assigned to active treatment. Surprisingly, patients assigned to placebo did not achieve improvement in symptoms. Those assigned to active treatment experienced a modest reduction in symptoms, the statistical parameters of which are influenced by the dropout rate. The suffering and the consequences that placebo-treated patients experience as a result of being denied the modest symptomatic improvement offered by active treatment warrants careful consideration.

|

|

|

|

Received July 11, 2000; revisions received Nov. 13, 2000, and Feb. 13, 2001; accepted Feb. 28, 2001. From the Northwest Clinical Research Center, Bellevue, Wash.; the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University, Durham, N.C.; the Department of Psychiatry, Brown University, Providence, R.I.; and Tufts University, Boston. Address reprint requests to Dr. Khan, 1900 116th Ave., N.E., Rm. 112, Bellevue, WA 98004; [email protected] (e-mail).

1. Shamoo AE, Irving DN: Accountability in research using persons with mental illness. Accountability in Res 1993; 3:1-17Google Scholar

2. Carpenter WT, Gold JM, Lahti AC, Queern CA, Conley RR, Bartko JJ, Kovnick J, Appelbaum PS: Decisional capacity for informed consent in schizophrenia research. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:533-538Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Code of Federal Regulations, Food and Drug Administration, 21, Parts 300 to 499, Revised as of April 1, 1997 (codified at 21 CFR 314.126), vol 5. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1997, pp 157-159Google Scholar

4. United States Department of Justice: Freedom of Information Act (FOIA): 5 US Congress:552 (1994 and Supplement II 1996). www.usdoj.gov/04foia/Google Scholar

5. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): recent developments in ascertaining and scaling. Psychopharmacol Bull 1988; 24:97-99Google Scholar

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Vital Statistics: Suicide Deaths and Rates per 100,000. www.cdc.gov/ncipc/osp/us9693/suic.htmGoogle Scholar

7. Reid WH, Mason M, Hogan T: Suicide prevention effects associated with clozapine therapy in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Psychiatr Serv 1998; 49:1029-1033Google Scholar

8. Meltzer HY, Okayli G: Reduction of suicidality during clozapine treatment of neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia: impact on risk-benefit assessment. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:183-190Link, Google Scholar

9. Khan A, Warner HA, Brown WA: Symptom reduction and suicide risk in patients treated with placebo in antidepressant clinical trials: an analysis of the Food and Drug Administration database. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:311-317Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Khan A, Khan S, Leventhal R, Brown WA: Symptom reduction and suicide risk in patients treated with placebo in antidepressant clinical trials: a replication analysis of the Food and Drug Administration Database. Int J Psychopharmacol (in press)Google Scholar

11. Meltzer HY: Suicide and schizophrenia: clozapine and the InterSePT Study: International Clozaril/Leponex Suicide Prevention Trial. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60(suppl 12):47-50Google Scholar