Season of Birth Among Patients With Schizophrenia and Their Siblings: Evidence for the Procreational Habits Hypothesis

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The birth rate of patients with schizophrenia during the winter and spring months is 5%–8% higher worldwide than the birth rate of the general population in the winter and spring months. Seasonal variation of births among the unaffected siblings of patients with schizophrenia has not been studied with adequate sample sizes. The authors investigated the seasonal variation of births among siblings of patients with schizophrenia in a large, nationwide, representative patient and sibling population. METHOD: Finnish patients with schizophrenia born from 1950 to 1969 (N=15,389) were identified from three nationwide health care registers. Unaffected siblings of these patients born in the same time period (N=37,819) were identified from the Finnish National Population Register. The seasonal variation of births among patients and siblings were examined by using a log-linear model. Explanatory variables were sex, year of birth categorized into four 5-year groups, and seasonal variation, which was analyzed by fitting a short Fourier series to the monthly birth data. RESULTS: The odds for having been born during the winter-spring months were slightly higher among both siblings and patients in all birth-year groups. However, patients born from 1955 to 1959 showed prominent seasonal variation of births, but the magnitude of this variation remained unchanged among siblings. CONCLUSIONS: Seasonal variation of births among patients with schizophrenia may consist of two factors: 1) parental procreational habits causing a slight excess of births of both patients and unaffected siblings during the winter-spring months and 2) irregular environmental factors that considerably increase the magnitude of the seasonal variation of births among patients but not their siblings.

The birth rate of patients with schizophrenia during the winter and spring months is 5%–8% higher worldwide than the birth rate of the general population in the winter and spring months. What causes this phenomenon is unknown. One hypothesis is that the seasonal conception pattern of parents of patients with schizophrenia is slightly different from that of the general population. This so-called procreational habits hypothesis predicts that the birth rate of the unaffected siblings of patients with schizophrenia should also be higher in the winter and spring (1).

Seasonal variation of births among siblings of patients with schizophrenia has been investigated in six studies (1–6), the largest of which involved 2,639 siblings. Two studies (2, 3) found a similar seasonal variation of births among siblings and patients that differed from the variation among the general population, but the other four (1, 4–6) found no difference between siblings and the general population. However, it is claimed that at least 4,500 subjects are needed if seasonal birth distribution is to be investigated by month (1). Therefore, the procreational habits hypothesis cannot be refuted until studied with adequate sample size.

With the aim of clarifying the issue, we set out to investigate seasonal variation of births among unaffected siblings of patients with schizophrenia in a nationwide, epidemiologically representative Finnish sample of patients with schizophrenia born from 1950 to 1969 and their unaffected siblings born in the same time period.

Method

We identified all Finnish patients born from 1950 to 1969 who had developed schizophrenia before 1992 using three nationwide health care registers: the National Hospital Discharge Register, the Pension Register, and the Free Medicine Register. Their siblings were identified by using the National Population Register, and information on siblings was linked to the health care registers to obtain data on their hospital treatments, pensions, and free medication (7). Schizophrenia was defined as a 295 diagnosis code according to ICD-8 and ICD-9; this code includes schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, and schizoaffective disorder.

We found 16,687 patients with schizophrenia (7), but we limited the study to patients born in Finland for whom information on siblings was available (N=15,389) and their unaffected siblings born from 1950 to 1969 (N=37,819). The Population Register Center provided sex-specific monthly numbers of births from 1950 to 1969 in each Finnish municipality, needed for the calculation of seasonal variation of births in the general population (8). To control for the seasonal variation in infant mortality (9, 10), only subjects who were alive at the end of 1969 were included. We observed in a previous study (8) that seasonal variation of births was prominent among patients with schizophrenia born from 1955 to 1959 but decreased considerably thereafter. Therefore, year of birth, divided into four 5-year groups (1950–1954, 1955–1959, 1960–1964, and 1965–1969), was used as an explanatory variable.

We used a modification of log-linear models that allows modelling of a response variable with multiple levels (11). The response variable had three categories (patient, sibling, and general population), and the explanatory variables were sex, year of birth, and seasonal variation. Seasonal variation was modeled by fitting a short Fourier series to the monthly birth data (12). Only the first harmonic was used because the higher harmonics were found not to be significant in our previous study of the patients (8). Results were presented as odds ratios with the general population as the reference category. It should be noted that observations of patients and their siblings are not independent. However, the lack of family information from the general population prevented us from applying correction methods such as general estimation equations or random effects model using family as a cluster. Because of the dependence in the data, presented p values are too low. However, it is highly unlikely that the inference is distorted because the number of observations in each cluster (family) is small. All analyses were performed with the statistical software S-PLUS, version 3.4 (13).

Results

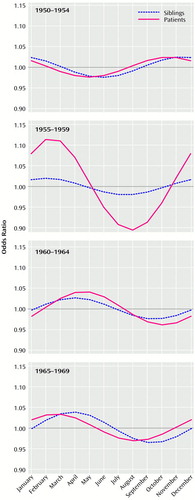

Monthly numbers of births among patients, siblings, and the general population in each birth year group are presented in Table 1, and results from modeling are presented in Figure 1. Seasonal variation of births among patients differed significantly from seasonal variation of births in the general population (χ2=22.0, df=6, p=0.001). No significant differences in the seasonal variation of births emerged between siblings and patients (χ2=12.0, df=6, p=0.06) and between siblings and the general population (χ2=7.0, df=6, p=0.32). Thus, seasonal variation of births among siblings seemed to lie intermediate between those observed among patients and among the general population. There was a significant interaction between year of birth and seasonal variation (χ2=28.9, df=12, p=0.004), which clarified the observed pattern. Both patients and siblings had slightly higher odds of being born during the winter and/or spring months in all birth year groups than the general population (Figure 1). However, the odds for being born between November and April were considerably higher among patients born from 1955 to 1959, but the magnitude of the increase among siblings remained unchanged (Figure 1).

Discussion

Our results support the procreational habits hypothesis: both patients and unaffected siblings had higher odds of being born in winter or spring months. Given the small sample sizes in previous studies, it is unsurprising that not all were able to detect this pattern of seasonal variation of births among siblings of patients with schizophrenia. Our study sample is epidemiologically representative in that it includes nearly all Finnish patients with schizophrenia and their siblings born from 1950 to 1969, which enhances the credibility of our findings.

The parental procreational habits hypothesis suggests that the seasonal conception pattern of parents of patients with schizophrenia differs from that of the general population. The late spring to early summer peak of births in the general population is thought to be caused by family planning, since summer is the most convenient time to care for a small baby in a cold climate (9). It might be that parents of patients with schizophrenia have exercised less family planning. Alternatively, the unusual seasonal pattern of conception could be the consequence of an unknown biological factor regulating fertility that somehow is associated with genetic liability to schizophrenia.

A second possibility is that there is an unusual seasonal pattern in the viability of fetuses among parents of patients with schizophrenia. It has been suggested that genes predisposing to schizophrenia confer greater robustness upon an infant—possibly already to a developing fetus. Perinatal mortality is higher in winter (9), and if infants of parents who carry genes predisposing to schizophrenia are more likely to survive, this could explain the observed excess of winter births of such individuals. However, previous studies have found that perinatal mortality is higher among mothers who have schizophrenia (14), speaking somewhat against the hypothesis. It has also been proposed that there might be a seasonally varying factor in the summer and fall that increases the risk of fetal loss among parents who carry genes predisposing to schizophrenia, causing the summer and fall deficit of births of patients with schizophrenia and their siblings (1).

The third explanation is that the seasonal conception pattern is not different but that preterm births are more common among parents of patients with schizophrenia. Some of the births that should have occurred during the spring peak of births in the general population would then occur earlier, causing a relative winter peak of births among patients with schizophrenia and their siblings compared with the general population. The fact that preterm deliveries are more common among mothers with schizophrenia (14, 15) lends some support to this hypothesis. Findings from the 1966 North Finland birth cohort suggest that it is not so much preterm birth itself but the combination of preterm birth and low birth weight that increases the risk of the later development of schizophrenia (16). If preterm births were more common among both patients and their siblings and only the combination of prematurity and low birth weight increased the risk of later developing schizophrenia, shorter gestation could explain the observed seasonality among patients and their unaffected siblings.

It is unlikely that the observed excess of winter-spring births among siblings was caused by the fact that some siblings had not yet developed schizophrenia. We have previously observed that winter birth was associated with early onset, while patients with onset after 30 years showed an autumn excess of births (8). Most of the siblings who had not developed schizophrenia by 1992 but did so thereafter would have belonged to this later-onset group.

An unknown factor caused the pronounced seasonal variation of births among patients born from 1955 to 1959 and the lack of such variation among unaffected siblings. We have hypothesized that two infectious diseases, poliomyelitis and influenza, may have caused the prominent seasonal variation among patients born from 1955 to 1959 (8). Severe, widespread epidemics of poliomyelitis occurred in Finland in 1954 and 1956, and epidemics of influenza occurred in 1953, 1955, and 1957. We have previously observed an association between second trimester exposure to poliomyelitis epidemics and schizophrenia (17), and the association between second trimester exposure to influenza epidemics and schizophrenia was first reported from Finland (18). Furthermore, the effects of both poliovirus (17) and influenza (19) have been more significant when seasonal variation has not been controlled for, suggesting that both infections may account for some of the observed seasonal variation of births in schizophrenia.

We conclude that the seasonal variation among patients with schizophrenia seems to consist of two components. One component is stable from year to year and originates in characteristics of the parents—either from a slightly different conception pattern or from a higher risk of preterm deliveries. As a result, both patients and their siblings are slightly more likely to have been born during the winter and spring months than the general population. The other component is caused by environmental risk factors that are present irregularly, such as infectious epidemics. When they occur, they cause pronounced seasonal variation of births among patients but not among their siblings and thus are probably genuine risk factors for schizophrenia.

|

Received June 27, 2000; revision received Oct. 17, 2000; accepted Nov. 3, 2000. From the Department of Mental Health and Alcohol Research, National Public Health Institute, Helsinki. Address reprint requests to Dr. Suvisaari, Department of Mental Health and Alcohol Research, National Public Health Institute, Mannerheimintie 166, FIN-00300 Helsinki, Finland; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grants from the Jalmari and Rauha Ahokas Foundation, the Maud Kuistila Foundation, and the Finnish Medical Foundation.

Figure 1. Odds for Patients With Schizophrenia and Their Siblings of Being Born in a Given Month Compared With the General Population in Finlanda

aThe odds ratios were produced by a log-linear regression model.

1. Torrey EF, Miller J, Rawlings R, Yolken RH: Seasonality of births in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a review of the literature. Schizophr Res 1997; 28:1–38Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. McNeil T, Kaij L, Dzierzykray-Rogalska M: Season of birth among siblings of schizophrenics. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1976; 54:267–274Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Hare EH: The season of birth of siblings of psychiatric patients. Br J Psychiatry 1976; 129:49–54Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Buck C, Simpson H: Season of birth among the sibs of schizophrenics. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 132:358–360Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Pulver AE, Liang K-Y, Wolyniec PS: Season of birth of siblings of schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry 1992; 160:71–75Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Torrey EF: The epidemiology of schizophrenia: questions needing answers, in Schizophrenia: Scientific Progress. Edited by Schulz SC, Tamminga CA. New York, Oxford University Press, 1989, pp 45–51Google Scholar

7. Suvisaari JM, Haukka J, Tanskanen A, Lönnqvist JK: Age at onset and outcome in schizophrenia are related to the degree of familial loading. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 173:494–500Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Suvisaari JM, Haukka JK, Tanskanen AJ, Lönnqvist JK: Decreasing seasonal variation of births in schizophrenia. Psychol Med 2000; 30:315–324Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Rantakallio P: The effect of a northern climate on seasonality of births and the outcome of pregnancies. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl 1971; 218:1–67Medline, Google Scholar

10. Hare EH, Moran PAP, MacFarlane A: The changing seasonality of infant deaths in England and Wales 1912–78 and its relation to seasonal temperature. J Epidemiol Community Health 1981; 35:77–82Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Palmgren J: The Fisher information matrix for log-linear models arguing conditionally in the observed explanatory variables. Biometrika 1981; 68:563–566Google Scholar

12. Jones RH, Ford PM, Hamman RF: Seasonality comparisons among groups using incidence data. Biometrics 1988; 44:1131–1144Google Scholar

13. S-PLUS, Version 3.4 for Unix Supplement. Seattle, MathSoft, Data Analysis Products Division, 1996Google Scholar

14. Wrede G, Mednick SA, Huttunen MO, Nilsson CG: Pregnancy and delivery complications in the births of an unselected series of Finnish children with schizophrenic mothers. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1980; 62:369–381Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Bennedsen BE, Mortensen PB, Olesen AV, Henriksen TB: Preterm birth and intra-uterine growth retardation among children of women with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 175:239–245Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Jones PB, Rantakallio P, Hartikainen A-L, Isohanni M, Sipilä P: Schizophrenia as a long-term outcome of pregnancy, delivery, and perinatal complications: a 28-year follow-up of the 1966 North Finland general population birth cohort. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:355–364Link, Google Scholar

17. Suvisaari J, Haukka J, Tanskanen A, Hovi T, Lönnqvist J: Association between prenatal exposure to poliovirus infection and adult schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1100–1102Google Scholar

18. Mednick SA, Machon RA, Huttunen MO, Bonett D: Adult schizophrenia following prenatal exposure to an influenza epidemic. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:189–192Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Takei N, Van Os J, Murray RM: Maternal exposure to influenza and risk of schizophrenia: a 22 year study from the Netherlands. J Psychiatr Res 1995; 29:435–445Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar