The Dexamethasone Suppression Test and Suicide Prediction

Abstract

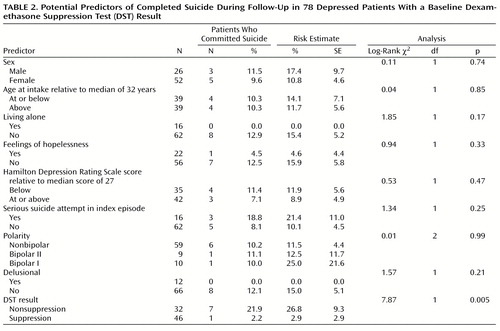

OBJECTIVE: Despite the substantial risks of eventual suicide associated with major depressive disorder, clinicians lack robust predictors with which to quantify these risks. This study compared the validity of demographic and historical risk factors with that of the dexamethasone suppression test (DST), a clinically practical measure of hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. METHOD: Seventy-eight inpatients with Research Diagnostic Criteria major depressive disorder or schizoaffective disorder, depressed type, entered a long-term follow-up study between 1978 and 1981, and, in addition, underwent a 1-mg DST. The number of suicides in this group during a 15-year follow-up period was determined, and the predictive validity of four demographic and historical risk factors reported in the literature to be consistently predictive of suicide in depressed patients was compared to the predictive validity of the DST results. RESULTS: Thirty-two of the 78 patients had abnormal DST results. Survival analyses showed that the estimated risk for eventual suicide in this group was 26.8%, compared to only 2.9% among patients who had normal DST results. None of the demographic and historical risk factors examined in the study significantly distinguished those who later committed suicide from those who did not. CONCLUSIONS: In efforts to predict and prevent suicidal behavior in patients with major depressive disorder, HPA-axis hyperactivity, as reflected in DST results, may provide a tool that is considerably more powerful than the clinical predictors currently in use. Research on the pathophysiology of suicidal behavior in major depressive disorder should emphasize the HPA axis and its interplay with the serotonin system.

The clinical management of patients with affective disorders requires an estimate of their risk for suicide, but the empirical basis for such estimates is tenuous. Of the three applicable study designs, one uses vital statistics to describe the demographic characteristics of those in the general population who commit suicide. This approach can test only a few risk factors, and the results do not generalize to clinical samples because a substantial proportion of those who commit suicide do so without seeking help for a psychiatric disorder. A second approach identifies diagnostically mixed patient groups, most often made up of patients who have threatened or attempted suicide, and compares those who subsequently complete suicide to those who do not. The diagnostic heterogeneity characteristic of these groups seriously limits conclusions. Many psychiatric disorders substantially increase the risk for eventual suicide, and the factors that predispose an individual to suicide in one illness may be unimportant in another. For example, recent loss and lack of social support are much more likely to precede suicide among alcoholics than they are among individuals who have primary depressive disorder (1, 2).

A third design, the follow-up of cohorts with specific disorders, is more likely to identify risk factors peculiar to a particular disorder. In a review of the English-language literature, we could find only four studies that assessed clinical predictors of completed suicide specifically among patients with major affective disorders (3–6). The studies differed considerably in the variables tested, and only a few predictors emerged with any consistency. In three of the four studies, a history of suicide attempts or the presence of suicidal ideation was more frequently found among those who later committed suicide (3–5) and, in another three studies, being unmarried and/or living alone were predictive (3, 4, 6). In two studies, male patients were at higher risk (3, 6).

Although further efforts may identify clinical profiles of more value as predictors, a search for relevant biological measures is clearly warranted. Among the biological abnormalities tentatively associated with risk for suicide, those involving the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis have shown particular promise. In postmortem studies, persons who died by suicide, in comparison to matched subjects who died by other violent means, had greater adrenal weights (7, 8), fewer binding sites for corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) in the frontal cortex (9), and higher levels of CRF in CSF (10). Each of these findings associates suicide with HPA-axis hyperactivity.

The dexamethasone suppression test (DST) offers a clinically practical means for detecting such hyperactivity and may therefore serve to estimate suicide risk. In the procedure used in the majority of studies, 1 mg of dexamethasone is administered orally at 11:00 p.m., and plasma cortisol levels are determined from blood samples drawn the following day at 8:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m. A value from either sample exceeding 5 μg/dl indicates failure to suppress cortisol and is considered evidence for HPA-axis hyperactivity.

Some studies have, in fact, found that patients with abnormal DST results were more likely to have recently made a suicide attempt (11–14) or were more likely to make future attempts (11, 15). Numerous authors have failed to find such relationships, though (16–20). There have been far fewer efforts to test HPA-axis disturbance as a predictor of completed suicide, but the results have been much more consistent.

Carroll et al. (21) identified five suicides from among 250 melancholic patients who had undergone the DST and noted that all had been nonsuppressors of cortisol, whereas this was true of only one-half of the remaining melancholic patients. Coryell and Schlesser (22) learned of four suicides from among 205 inpatients with primary unipolar depression who had undergone the DST while hospitalized. All of these, but less then half (45.8%) of the remaining patients, had been nonsuppressors. Finally, Norman et al. (23) drew from a large sample of depressed inpatients with DST results and matched the 13 who subsequently committed suicide both to other patients who had attempted suicide before admission and to patients who had not attempted suicide. Again, approximately one-half (54%) of those who later committed suicide were nonsuppressors at 4:00 p.m., compared with 28% of those who had not attempted suicide and only 8% of those with a previous attempt.

These studies of completed suicide did not test the relative value of other clinical predictors. This leaves the possibility that DST results served as a proxy for features such as delusions, overall symptom severity, hopelessness, or a history of mania. Moreover, the observation periods were limited. Carroll et al. (21) did not describe the length of follow-up, and the other two studies averaged less than 3 years of observation (23, 24).

The earlier report from this center concerning serious suicide attempts and DST results (15) described patients who entered the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Study of the Affective Disorders—Clinical Branch, a long-term follow-up of patients who met Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (25) for major depressive disorder, mania, or schizoaffective disorder. Although the baseline assessment for the Collaborative Depression Study included only demographic and clinical variables, a large proportion of those who entered the study as inpatients at the University of Iowa center underwent a 1-mg DST as part of their routine clinical assessment. Follow-up has continued since the original report on suicide attempts, and a number of suicides have occurred in the interval. This study examines the relationship between DST results and these suicides. Because all subjects underwent structured phenomenological assessments at baseline, the relative importance of clinical predictors can also be examined.

Method

Subjects

Between 1978 and 1981, inclusive, patients who sought treatment as inpatients or outpatients for conditions that met RDC for major depressive disorder, mania, or schizoaffective disorder were recruited into the Collaborative Depression Study. Participants were age 18 or older, white, and English speaking. The current analysis was restricted to inpatients recruited at the University of Iowa center.

Procedures

All subjects provided written informed consent after being given a complete description of the study. Diagnoses were based on the full Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) (26), which combined information from direct interviews and medical records. Follow-up interviews, structured by the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (27), took place at 6-month intervals for the next 5 years and annually thereafter. The protocol did not determine or influence treatment, but ongoing somatotherapies were methodically monitored and quantified, as described elsewhere (28).

DSTs were not part of the Collaborative Depression Study protocol. The patients described in this report received them in one of two ways. A formal research protocol, described elsewhere (29), included the DST and overlapped with the period of intake for the Collaborative Depression Study. Other patients received the DST because it was ordered by the treating physician, as was often done during the period of intake for the collaborative study. In either case, the patient took 1 mg of dexamethasone orally at 11:00 p.m. and provided blood samples the next day at 8:00 a.m. and/or 4:00 p.m. Cortisol levels were determined by a competitive protein-binding assay (30). A cortisol value greater then 5 μg/dl in either postdexamethasone sample indicated nonsuppression of cortisol. For the patients assessed in the protocol of Schlesser et al. (29), the designation as suppressor or nonsuppressor, but not the actual postdexamethasone cortisol value, remained available for this analysis. The results are therefore limited to this categorical grouping.

In most cases, raters learned of suicides as they attempted to reach the patient for the next follow-up interview. In all cases of death, raters sought to obtain descriptions of the circumstances from informants, from the death certificate, and from pertinent medical records. They then made a judgment of whether the death was due to suicide. Raters were not formally blinded to the DST results, and the cortisol values from tests ordered outside of the Schlesser et al. (29) protocol were recorded in the hospital charts. These results were not, however, among the variables assessed by raters in the Collaborative Depression Study.

Statistical Analysis

Three potential predictors of suicide—male sex, living alone, and the presence of a suicide attempt during the index illness episode before intake—were selected on the basis of the previously described literature review. The presence of hopelessness in the week preceding intake was also considered because it has been a particularly robust predictor of suicide in diagnostically mixed samples (31, 32). Hopelessness was considered present if the SADS item that quantified “discouragement, pessimism, and hopelessness” (item 244) was scored 4, 5, or 6 (“moderate,” “severe,” or “extreme”) for the worst week of the index episode. Because some reports have found polarity to be predictive of eventual suicide (33, 34), this variable was tested as well.

Each potential predictor was dichotomized, and the two resulting groups compared by using nonparametric Kaplan-Meier procedures (35). These procedures included censored data that resulted from loss to follow-up to derive risk estimates and to compute log-rank tests for group comparisons. Alpha was set at 0.05. The results presented here also include the simple proportions of those followed who were known to have committed suicide. The variables that generated a p value less than 0.1 were entered into a regression analysis in which risk for suicide was the dependent variable. Baseline differences between suppressors and nonsuppressors in the proportion of subjects with individual risk factors were analyzed by using two-by-two chi-square tests with continuity adjustments.

Results

Of the 246 probands who entered the Collaborative Depression Study at the Iowa site, 83 underwent a DST within 1 week of admission. Excluding the 13 patients known to have died during follow-up, 61 (87.1%) completed at least 2 years of follow-up, and 44 (62.9%) completed at least 15 years. Some follow-up information was available for 78 patients. These 78 differed from the remaining 151 patients followed at the Iowa site in three of the baseline variables listed in Table 1 and Table 2: those who received a DST were less likely to have psychotic features (N=12 [15.4%] versus N=41 [27.2%]) (χ2=4.0, df=1, p<0.05), less likely to have bipolar I disorder (N=10 [12.8%] versus N=56 [37.1%]) (χ2=13.6, df=1, p=0.0002), and more likely to have made a serious suicide attempt (N=16 [20.5%] versus N=12 [7.9%]) (χ2=7.6, df=1, p<0.006). The underrepresentation of patients with bipolar I disorder among those receiving the DST was expected because many of these patients entered the study in a manic phase and the DST was rarely used with such patients.

Of the 78 patients with DST results, 32 (41.0%) had an 8:00 a.m. and/or 4:00 p.m. postdexamethasone cortisol level greater then 5 μg/dl and were considered nonsuppressors. Nonsuppressors were significantly more likely than suppressors to have an intake diagnosis of bipolar I disorder (Table 1). Otherwise, the groups did not differ significantly in baseline demographic measures or diagnostic category.

Eight suicides were identified, and a death certificate was obtained for each. Seven of the certificates listed the primary cause of death as suicide. The remaining death certificate listed the immediate cause of death as carbon monoxide asphyxiation and further specified that this was a consequence of depression.

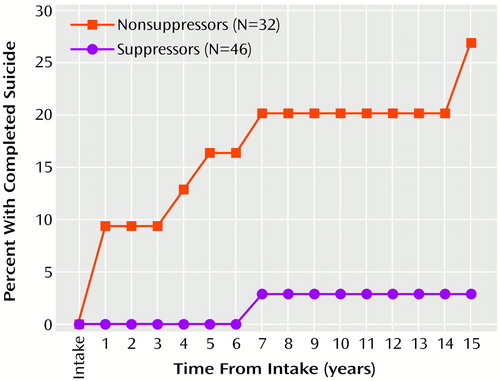

Of the eight subjects whose suicides were identified during the follow-up period, seven (87.5%) had a DST result indicating nonsuppression of cortisol during their index hospitalization (Figure 1). The disparity between suppressors and nonsuppressors in the likelihood of suicide increased throughout the 15 years of follow-up.

None of the other variables selected as likely predictors of suicide proved to be so in this group of patients (Table 2). Nor was there a significant relationship between the likelihood of suicide and age, symptom severity, polarity, or the presence of delusions. Only the presence or absence of a serious suicide attempt in the index episode preceding study intake generated a p value less than 0.1. This variable was entered together with DST suppressor status as an independent variable in a regression analysis of the likelihood of suicide. In this model, nonsuppression increased the likelihood of future suicide 14-fold (odds ratio=14.3, Wald χ2=5.6, p=0.02). A serious suicide attempt in the index episode generated an odds ratio of 3.8 (Wald χ2=2.3, p=0.13).

Discussion

These results support the view, based largely on postmortem evidence, that HPA-axis hyperactivity is a characteristic of patients with major depressive disorder who commit suicide. Although this finding has obvious relevance to the possible pathogenesis of serious suicidal behavior in major depressive disorder, it also has practical significance. None of the variables selected from the literature as likely risk factors were significantly predictive in this cohort. Even the most intuitively compelling of these—a serious suicide attempt earlier in the index episode—was not significantly more frequent among the patients who eventually committed suicide. In contrast, HPA-axis hyperactivity at baseline increased the odds of an eventual suicide 14-fold.

The fact that suppressors and nonsuppressors had cumulative probabilities of suicide that continued to diverge across 15 years of follow-up indicates that the suicide risk implied by a positive DST result is an enduring one. The simplest view of this finding presumes that the propensity to HPA-axis hyperactivity during a given major depressive episode is a characteristic of an individual’s lifetime illness. Although the few efforts to study the stability of DST results over time have shown only modest test-retest reliability (24, 36), high correlations have been demonstrated between postdexamethasone cortisol levels obtained during separate hospitalizations (24).

The eight suicides in this report include three of the five suicides described by Coryell and Schlesser (22). The present study is therefore an extension, rather than a replication, of the earlier study. Thus, three nonoverlapping studies have associated nonsuppression of cortisol with markedly higher risks for subsequent suicide among patients hospitalized for depression. The current study is also an extension of an earlier analysis of this cohort in which nonsuppressors were significantly more likely to make suicide attempts that were considered psychologically serious during follow-up (15).

This is a surprising degree of consistency given the temporal instability of DST results demonstrated in earlier studies (24, 36). It is also noteworthy that nonaffective disorders such as schizophrenia, alcoholism, and drug dependence also carry substantial suicide risks. DST results in these disorders, even in the context of a superimposed depressive disorder, may not have the same predictive value as they do in primary depressive disorder. This possibility could not be assessed in the current study group, given its limited size and composition. Thus, the use of DST results to quantify risk for eventual suicide should, pending contrary evidence, be confined to patients for whom major depressive disorder has been the dominant illness over time.

The inclusion criteria used in the Collaborative Depression Study are also relevant to generalizability. No African Americans were included, and the patients studied at the Iowa center were otherwise more culturally homogenous than patient samples in many other settings. More research will be necessary to determine whether these findings can be applied in diverse populations.

The DST is subject to a number of confounds that could not be rigorously controlled in this data set. These include a variety of medications and medical illnesses. Although the DST was generally not administered in circumstances thought to invalidate the results, the presence or absence of these factors was not adequately documented in these data. Such factors as plasma level variability (37, 38) and the stress associated with hospital admission (39) have also been thought to influence DST results, but it has not been clearly shown that the control of these variables improves the diagnostic performance of the DST. In as much as such variables are confounds, their influence would tend to produce false negative results, and this was clearly not the outcome here.

Evidence for an association between nonsuppression of cortisol and suicide risk seems strong. That HPA-axis hyperactivity is a far more robust predictor than other clinical variables clearly needs independent replication. Given the widespread use of the DST in the early 1980s, there are many potential cohorts that could be followed to further test this finding.

These findings also underscore the importance of the HPA axis in the pathophysiology of suicide. Although the serotonin system has been the major focus of biological research on suicide (40, 41), there is now substantial evidence that HPA-axis abnormalities may underlie serotonin abnormalities in the genesis of suicidal behavior (42). Further attention to the interplay between these systems in suicidal behavior is clearly warranted. Whichever system eventually proves to be the more etiologically fundamental, it appears that, at present, HPA-axis hyperactivity is the more clinically accessible, and therefore more clinically useful, of the two.

|

|

Received June 16, 2000; revisions received Oct. 12 and Nov. 20, 2000; accepted Nov. 28, 2000. From the Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa College of Medicine; and Dallas Neuropsychiatry Associates, Dallas, Tex. Address reprint requests to Dr. Coryell, Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa College of Medicine, 2-205 MEB, Iowa City, IA 52242-1000.Supported in part by NIMH grants MH-51324 and MH-25416.

Figure 1. Cumulative Probabilities of Suicide Among Depressed Patients by Baseline Dexamethasone Suppression Test Resultsa

aLog-rank χ2=7.9, df=1, p=0.005.

1. Barraclough B, Bunch J, Nelson B, Sainsbury P: A hundred cases of suicide: clinical aspects. Br J Psychiatry 1974; 125:355–373Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Murphy GE, Wetzel RD, Robins E, McEvoy L: Multiple risk factors predict suicide in alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:459–463Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Barraclough BM, Pallis DJ: Depression followed by suicide: a comparison of depressed suicides with living depressives. Psychol Med 1975; 5:55–61Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Roy A: Suicide in depressives. Compr Psychiatry 1983; 24:487–491Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Fawcett J, Scheftner WA, Fogg L, Clark DC, Young MA, Hedeker D, Gibbons R: Time-related predictors of suicide in major affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1189–1194Google Scholar

6. Newman SC, Bland RC: Suicide risk varies by subtype of affective disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991; 83:420–426Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Dorovini-Zis K, Zis AP: Increased adrenal weight in victims of violent suicide. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:1214–1215Google Scholar

8. Szigethy E, Conwell Y, Forbes NT, Cox C, Caine ED: Adrenal weight and morphology in victims of completed suicide. Biol Psychiatry 1994; 36:374–380Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Nemeroff CB, Owens MJ, Bissette G, Andorn AC, Stanley M: Reduced corticotropin releasing factor binding sites in the frontal cortex of suicide victims. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:577–579Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Arato M, Banki CM, Bissette G, Nemeroff CB: Elevated CSF CRF in suicide victims. Biol Psychiatry 1989; 25:355–359Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Targum SD, Rosen L, Capodanno AE: The dexamethasone suppression test in suicidal patients with unipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:877–879Link, Google Scholar

12. Banki C, Arato M, Papp Z, Kurcz M: Biochemical markers in suicidal patients. J Affect Disord 1984; 6:341–350Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Lopez-Ibor JJ, Saiz-Ruiz J, Pereze de los Cobos JC: Biological correlations of suicide and aggressivity in major depressions (with melancholia):5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid and cortisol in cerebral spinal fluid, dexamethasone suppression test and therapeutic response to 5-hydroxytryptophan. Neuropsychobiology 1985; 14:67–74Google Scholar

14. Pfeffer CR, Stokes P, Shindledecker R: Suicidal behavior and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis indices in child psychiatric inpatients. Biol Psychiatry 1991; 29:909–917Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Coryell W: DST abnormality as a predictor of course in major depression. J Affect Disord 1990; 19:163–169Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Brown RP, Mason B, Stoll P, Brizer D, Kocsis J, Stokes PE, Mann JJ: Adrenocortical function and suicidal behavior in depressive disorders. Psychiatry Res 1986; 17:317–323Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Secunda SK, Cross CK, Koslow S, Katz MM, Kocsis J, Maas JW, Landis H: Biochemistry and suicidal behavior in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry 1986; 21:756–767Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Ayuso-Gutierrez J, Cabranes J, Garcia-Camba E, Almoguera I: Pituitary-adrenal disinhibition and suicide attempts in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry 1987; 22:1409–1412Google Scholar

19. Schmidtke A, Fleckenstein P, Beckmann H: The dexamethasone suppression test and suicide attempts. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1989; 79:276–282Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Roy A: Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function and suicidal behavior in depression. Biol Psychiatry 1992; 32:812–816Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Carroll BJ, Greden JF, Feinberg M: Suicide, neuroendocrine dysfunction and CSF 5-HIAA concentrations in depression, in Recent Advances in Neuropsychopharmacology: Proceedings of the 12th CINP Congress. Edited by Angrist B. Oxford, UK, Pergamon Press, 1980, pp 307–313Google Scholar

22. Coryell W, Schlesser MA: Suicide and the dexamethasone suppression test in unipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 1981; 138:1120–1121Google Scholar

23. Norman WH, Brown WA, Miller IW, Keitner GI, Overholser JC: The dexamethasone suppression test and completed suicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1990; 81:120–125Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Coryell W, Schlesser MA: Dexamethasone suppression test response in major depression: stability across hospitalizations. Psychiatry Res 1983; 179–189Google Scholar

25. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) for a Selected Group of Functional Disorders, 3rd ed. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1978Google Scholar

26. Endicott J, Spitzer RL: A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:837–844Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielsen E, Endicott J, McDonald-Scott P, Andreasen NC: The Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation: a comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:540–548Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Mueller TI, Endicott J, Coryell W, Hirschfeld RM, Shea T: Time to recovery, chronicity, and levels of psychopathology in major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:809–816Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Schlesser MA, Winokur G, Sherman BM: Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in depressive illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980; 37:737–743Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Murphy BEP, Patee CJ: Determination of plasma corticoids by competitive protein-binding analysis using gel filtration. Endocrinology 1964; 24:919–923Google Scholar

31. Beck AT, Steer RA, Kovacs M, Garrison B: Hopelessness and eventual suicide: a ten-year prospective study of patients hospitalized with suicidal ideation. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:559–563Link, Google Scholar

32. Beck AT, Brown G, Berchick RJ, Stewart BL, Steer RA: Relationship between hopelessness and ultimate suicide: a replication with psychiatric outpatients. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:190–195Link, Google Scholar

33. Morrison JR: Suicide in a psychiatric practice population. J Clin Psychiatry 1982; 43:348–352Medline, Google Scholar

34. Black D, Winokur G, Nasrallah A: Suicide in subtypes of major affective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:878–880Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL: The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1980, pp 12–15Google Scholar

36. Coryell W, Smith R, Cook B, Moucharafieh S, Dunner F, House D: Serial dexamethasone suppression test results during antidepressant therapy: relationship to diagnosis and clinical change. Psychiatry Res 1983; 10:165–174Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Johnson GF, Hunt GE, Caterson I: Plasma dexamethasone and the dexamethasone suppression test. J Affect Disord 1988; 15:93–100Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. O’Sullivan B, Hunt G, Caterson I: The plasma dexamethasone window: evidence supporting its usefulness to validate dexamethasone suppression test results. Biol Psychiatry 1989; 25:739–754Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Szadoczky E, Rihmer Z, Arato M: Influence of hospital admission on DST results in patients with panic disorder (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:1315–1316Google Scholar

40. Mann JJ, McBride PA, Brown RP, Linnoila M, Leon AC, DeMeo M, Mieczkowski T, Myers JE, Stanley M: Relationship between central and peripheral serotonin indexes in depressed and suicidal psychiatric inpatients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:442–446Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Mann JJ, Malone KM, Sweeney JA, Brown RP, Linnoila M, Stanley B, Stanley M: Attempted suicide characteristics and cerebrospinal fluid amine metabolites in depressed inpatients. Neuropsychopharmacology 1996; 15:576–586Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Lopez JF, Vazquez DM, Chalmers DT, Watson SJ: Regulation of 5-HT receptors and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Ann NY Acad Sci 1997; 836:106–134Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar