The Response Evaluation Measure (REM-71): A New Instrument for the Measurement of Defenses in Adults and Adolescents

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: There is widespread agreement that the concept of defense is useful, but large-scale studies with representative cohorts are lacking. Self-report measures capturing conscious derivatives of defense can facilitate such studies. The authors report the design and initial performance of a new self-report measure of specific defenses. METHOD: A 71-item questionnaire based on a developmental model of defenses was created, pilot tested, and refined. The item pool was given to two independent clinical researchers for the classification of items (concordance=98.5%). The instrument was then administered to 1,875 nonclinical subjects drawn from two suburban high schools and from a public waiting area of a local airport (1,038 female subjects; mean age=21.0 years, SD=11.9, range=13–89), who were also assessed with a simple screening measure covering demographic variables and satisfaction with life. RESULTS: The internal consistency of the questionnaire items was good. Two factors emerged from a factor analysis of the items, paralleling Vaillant’s theoretical model. Most defenses made unique, significant contributions to these factors. Defenses and factors related in the expected direction with scores on life satisfaction in various domains. CONCLUSIONS: The Response Evaluation Measure is a brief, coherent, and potentially useful screening instrument for the assessment of defenses in adults and adolescents.

Give me deception which brings happiness rather than truth that crushes me.

— Christoph Martin Wieland (1)

The concept of defense is one of Freud’s most original contributions (2–4). Defenses are hypothesized to function at an unconscious level to prevent painful affects and ideas from entering awareness (5, 6), making it difficult to measure them appropriately.

Despite methodological problems, the construct of defense has proven to be robust. A growing body of literature relates defense style to several domains of psychosocial functioning (7, 8), including temperament (9), family characteristics (10), and stressful life events (11). Prospective studies show the predictive power of defenses for mental and physical health (3, 4, 8). Other studies relate defenses to psychopathology (6, 8, 12–16).

By definition, defenses represent a distortion of unwelcome reality (DSM-IV, p. 751; references 4, 5, and 17). Not all defenses distort reality to the same degree. They are often organized along developmental or adaptive continua that reflect the degree to which they distort reality (3, 4, 17–19). Only some studies have tested these models in children and in adults (7–17).

The elusive nature of defenses has generated disparity regarding their number and their definitions. Some researchers propose a wide range of defenses (4, 6), while others list an essential eight (18). In part, these difficulties persist because large, representative samples have not been studied. During the past 30 years, studies often involved a limited number of defenses, small groups of subjects, and observer methods with their attendant problems of stability and interrater reliability (3, 4, 19). The result is a variety of defenses and theoretical hierarchies (4, 13, 17–21).

Population-based research requires simple, reliable measures. Although the efficacy of self-report measures has been questioned, we argue along with others that subjects are able to report on the conscious derivatives, from which the defenses themselves can be inferred (4, 6, 13, 15, 18, 20, 21). Self-report measures can offer advantages. Items written appropriately avoid the confounding of dependent and independent variables. Research relying on interview or vignette data often exposes the rater to specific defenses, along with the outcomes of those processes, which can influence how positively particular defenses are viewed. Self-report measures present standardized stimuli. Self-report measures are less labor-intensive than observer ratings.

Initially, our group used a modification (12, 13, 21, 22) of the Defense Style Questionnaire of Bond et al. (20). The Defense Style Questionnaire was selected for our studies because of its developmental underpinnings. Evidence of its reliability and validity had been derived in both cross-sectional and longitudinal research (4, 6, 8, 14, 20, 21). However, it contained serious psychometric limitations that we addressed, first, by modifying it extensively and, finally, when certain psychometric limitations could not be overcome, by developing a new measure (12, 13, 21) (details described in Method section).

In this study we report on the development and validation of this new 71-item self-report measure, the Response Evaluation Measure (REM-71). We defined defense as follows. In contrast to coping, defending primarily functions to exclude information (22, 23). Defense is an unconscious reaction, not a planned response, forming an interface between innate temperament traits and learned coping strategies (2–23). Defenses are ubiquitous, not intrinsically pathological (4, 5, 17, 18).

This research had four aims: 1) to assess the validity and reliability of the REM-71 as a self-report measure of defenses, 2) to evaluate the structure of defenses by factor analysis, 3) to test sex and age differences, and 4) to examine the relationships between defense and psychosocial health.

We hypothesized that defenses would be organized along two continua similar to the “immature” and “mature” clusters that have been most robust across previous studies (4, 6, 8, 13, 20, 21). The immature cluster contains defenses that distort reality in accordance with expected outcomes, leading to less adaptive functioning. Mature defenses attenuate unwelcome reality, allowing more adaptive functioning.

Regarding gender differences, we hypothesized that there would be male/female differences, as we found previously (13, 21) and as a related body of literature suggests (24, 25). Therefore, we expected action-oriented defenses (e.g., acting out) or dominance-driven defenses (e.g., omnipotence) to be more highly endorsed by male subjects and internalizing and affiliation-related defenses (e.g., altruism) more highly endorsed by female subjects.

Regarding developmental differences, we hypothesized that adolescents would have higher scores for immature defense but lower scores for mature defenses, as in previous studies (13).

Finally, we examined whether defenses are associated with psychosocial health in several domains. In line with longitudinal studies of defense and adaptation (3, 4, 8, 19), we hypothesized that greater use of mature defenses would predict greater satisfaction with life, while greater use of immature defenses would predict less life satisfaction.

Method

Subjects

The study was approved for passive consent by our institutional review board. Passive consent was indicated by the agreement of students in two local suburban high schools to participate in our survey. Of the students surveyed, 89% returned valid surveys. Of these 1,487 students, 45% were male (N=663); their mean age was 15.9 years (SD=1.2, range=13–20). Their parents’ employment levels were average for the region (94% of fathers and 82% of mothers were employed; 77% of the students came from two-income homes).

To compare our findings with those in the existing literature on adults, a sample of convenience was recruited from a public waiting area of a local airport. These 388 adults were predominantly Caucasian, 45% were male (N=174), and they ranged in age from 20 to 89 years old (mean=40.4, SD=14.3). Approximately 28% of those asked declined to participate. The subjects completed the questionnaires anonymously.

Measure of Defenses

The REM-71 was designed as a departure from the 78-item modified Defense Style Questionnaire (12, 13, 21). (The instrument and its scoring instructions are available from Dr. Steiner on request.) Instrument development took place in several steps designed to address specific problems with the Defense Style Questionnaire. Since several defenses contained in that instrument were not widely accepted in the literature (e.g., task orientation), a list of defenses was generated on the basis of predominance in the literature and presence in glossaries of defenses (4, 18, 19, 23). Defenses close to DSM definitions of disorders and psychiatric syndromes (e.g., consumption of substances) were excluded. Similar defenses were removed (for instance, inhibition was removed because of its proximity to withdrawal). Finally, we excluded defenses related to coping strategies (e.g., anticipation) (23), resulting in a final list of 21 defenses (Table 1).

The items were worded to avoid the overtly pathological wording of the Defense Style Questionnaire (e.g., “Some people are plotting to kill me”) and extreme language (“always,” “never”). This approach was both theoretically and psychometrically preferable, reducing the likelihood of floor effects. Phrases involving outcomes, often included in the Defense Style Questionnaire, were removed to avoid the confound of dependent and independent variables (e.g., “I get satisfaction from helping others and if this were taken away from me I would get depressed” [emphasis added]). We avoided the complex item structure that rendered the meaning of some items ambiguous (e.g., “People say I’m like an ostrich with my head buried in the sand. In other words, I tend to ignore unpleasant facts as if they didn’t exist.”). Each defense was represented by a minimum of three and a maximum of four items, to address a central psychometric difficulty inherent in the Defense Style Questionnaire: overrepresentation of some defenses (e.g., projection, with nine items) and underrepresentation of others (e.g., fantasy, with one item [13]). During this revision process, 93% of the Defense Style Questionnaire items were rewritten for middle school reading level or omitted. Finally, the items were randomized to avoid the clustering evident in the Defense Style Questionnaire.

In writing new items, we consulted several glossaries (3, 4, 17–20, 23, 26). Sets of 10–12 new items covering each of several defenses were pilot tested on small groups of clinic and school subjects not involved in this study. Cronbach’s alpha scores for these data were used to derive the best subset of items.

Using this iterative process, we defined a final set of 66 items assessing 21 defenses. Three defenses were represented by four items each, while the remaining 18 defenses were each represented by three items. All but one of the alpha values were above 0.40 (mean=0.58). For passive-aggression, the alpha correlation was below 0.40. However, each item correlated significantly with the other two in the set (0.20<r<0.25, p<0.0001), and the overall alpha correlation was strengthened by the inclusion of each item. We decided to retain the defense as it was pending testing in a clinically diverse study group.

To assess construct validity, the resulting REM-71 was given to two independent clinical researchers with instructions to assign each item to one or more defenses by using either Vaillant’s defenses (4) or the DSM-IV glossary of defenses (pp. 755–757). There was agreement on all but one item, and agreement on this item was readily reached by discussion.

To round out the instrument, four neutral items and one lie item were added, bringing the total to 71. Subjects rated their endorsement of each item on a 9-point scale from “strongly disagree” (scored as 1) to “strongly agree” (scored as 9). The score for each defense is the average of the scores for the items representing that defense.

Measures of Psychosocial Functioning

To test the hypothesis regarding defense and self-report of psychosocial functioning, five additional items were included in the survey. Using a 9-point scale from “very unsatisfied” (scored as 1) to “very satisfied” (scored as 9), subjects were asked to indicate their satisfaction in the domains of work, family, friendships, and recreation and to respond to a general statement of satisfaction. These items have a high degree of face validity.

Statistical Analysis

We used principal components factor analysis (27, p. 395), parallel analysis (27, p. 373; 28, p. 79), analyses of covariance, and multiple regressions as appropriate.

Results

Factor Analysis

Our first goal was to do an exploratory principal components analysis of the 21 defenses. Kaiser’s measure of sampling adequacy showed a sufficient number of subjects (27). To determine the optimal number of factors to retain, two statistical guidelines were used. First, the eigenvalue distribution (i.e., scree test) indicated a three-factor solution. Second, using parallel analysis, we compared the empirically derived eigenvalues to the eigenvalues resulting from a series of Monte Carlo simulations of our data. The averaged results of five Monte Carlo runs indicated that retention of a third factor was questionable, since the eigenvalue of the empirically obtained third factor was not significantly greater than what would be expected by chance. Initial principal components analyses resulted in two interpretable solutions: an unrotated two-factor solution and a three-factor solution using varimax rotation. We report on both the unrotated and rotated solutions (Table 2). For both solutions, only positive loadings were used, and loadings above 0.35 were considered significant when the difference in loadings between factors was at least 0.20.

In the unrotated solution, factor 1 contained 14 defenses. Two defenses (sublimation and omnipotence) had loadings on the second factor that were within 0.20 of their factor 1 loadings. Since the factor 2 loadings were below 0.35, both defenses were included in the factor 1 summation. This factor accounted for 22.9% of the variance and had an alpha correlation of 0.84. Factor 2 contained seven defenses. This factor accounted for 13.8% of the variance and had an alpha correlation of 0.69.

The rotated factor solution used varimax rotation to maximize the variance accounted for by each factor (27, p. 399; 29; 30, p. 201), and it yielded three factors. The first factor accounted for 19.8% of the variance and contained 11 defenses. Factor 2 contained five defenses accounting for 12.2% of the variance. Factor 3, accounting for 10.5% of the variance, contained four defenses. A fifth defense, undoing, loaded significantly on each factor, with the highest loading on factor 2. It was therefore included in this factor. Alpha correlations for the three factors are presented in Table 2.

Age and Gender Differences

To test for age and gender effects in the magnitude of defense use, we performed analyses of variance (ANOVAs) by age and gender with the Waller-Duncan K ratio (28, p. 121) to identify the direction of difference (Table 3). As is evident from these analyses, there were significant age and gender effects. As predicted, adolescents had higher mean scores than adults for each factor 1 defense except somatization. The age effects for factor 2 defenses were mostly as expected, i.e., showing higher scores for older subjects, but two defenses (altruism and idealization) showed the opposite pattern, and one (reaction formation) was the same in all three groups.

One-half of the defenses showed marked gender effects. Among factor 1 defenses, female subjects reported greater use of somatization, splitting, sublimation, and undoing, while male subjects had higher scores for omnipotence, passive-aggression, and repression. Acting out, conversion, displacement, dissociation, fantasy, projection, and withdrawal showed no differences across gender. For the defenses in factor 2, female subjects had higher scores for altruism, idealization, and reaction formation, while male subjects had higher scores for denial (isolation of affect), intellectualization, and suppression.

Satisfaction With Life and Self

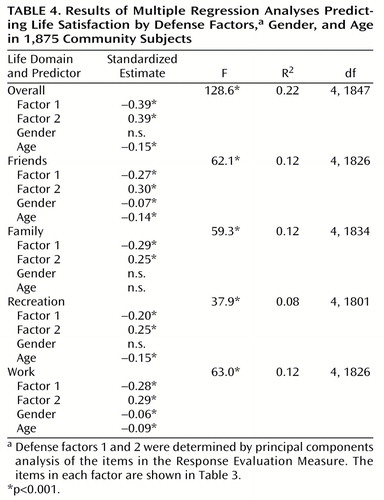

Using several multiple regression equations and controlling for gender and age, we examined the relative contribution of factors 1 and 2 in predicting reported satisfaction with work, recreation, family, friends, and self in general. For the entire study group, the net effect of defense style (factor 1 versus factor 2) was more important than that of either gender or age in predicting scores in each of the five domains. In each domain, lower factor 1 and higher factor 2 defense scores predicted higher scores (Table 4).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study using a psychometrically balanced self-report instrument to assess defenses in a large, heterogeneous group of adolescents and adults. Exploratory principal components analysis of 21 defenses yielded two interpretable solutions: an unrotated, two-factor solution and a rotated, three-factor solution. Additional analyses, using ANOVAs, revealed age and gender differences. Regression analyses indicated that defense style was a significant correlate of psychosocial functioning.

Defense Structure Revealed by the REM-71

While the initial analysis of our data showed that either a two- or three-factor solution was acceptable, we suggest that the unrotated, two-factor model is the preferred solution. Three considerations guided this recommendation. First, an unrotated solution preserved orthogonality of factors, a quality often dimmed by rotation methods (27, p. 399). Second, the results of the parallel analysis suggested that the two-factor solution is less likely to capitalize on chance. Third, the three-factor solution only increased the explained variance by 5%. However, this is a question for further study. It is possible that the inclusion of clinical study groups may strengthen one solution over the other. We present both for comparison.

The two-factor defense structure differs from previous findings and theory. Whereas earlier research summarized the nonpsychotic defenses in three groups—“immature,” “neurotic” (or “prosocial”), and “mature” (4, 13)—the current research reveals a two-dimensional defense organization that, while broadly comparable to previous findings and paralleling Vaillant’s theoretical model, contains aspects that are unexpected. These two factors possessed high internal cohesion (Table 1) and were only moderately correlated with one another (r=0.19, p=0.0001), indicating their distinctive contributions to the adaptive effort.

The most notable shifts in the makeup of the two factors were the presence of sublimation within the first factor and of denial (isolation of affect) in the second factor. Although the factor loadings of sublimation are complex, being significant on both factors, the stronger loading on factor 1 may be explained in part by studies linking emotional distress, psychopathology, and overly inclusive thought processes to expressly creative endeavors (31).

The unambiguous alignment of denial (isolation of affect) with the second factor also differs from traditional thinking. While clinician raters correctly labeled each denial item, the items did not refer to “psychotic denial” of overt reality but to denial of affective responses. There is empirical evidence that positive outcomes are associated with use of denial (isolation of affect) in this fashion, leading some to question denial’s unwavering association with maladaptive outcomes (32).

Labeling the two factors is in process. The terms “immature” and “mature” are problematic because they are ambiguous, referring to either a developmental construct, whereby different defenses are acquired at different ages (4, 13, 17), or relative adaptive efficacy. Added to this ambiguity is the implication that they occur on a continuum. However, this research shows the two factors to be only modestly correlated and orthogonal. Future studies will aim in part at defining and labeling the basic process inherent in each factor.

Gender and Age Differences

No gender difference was found in the level of endorsement for either factor, suggesting that neither factor was predominantly the domain of either male or female subjects. Nevertheless, the defenses endorsed more strongly by females (somatization, reaction formation, altruism, sublimation, idealization, splitting) reflect an internalizing, relationship-focused defense style, whereas defenses endorsed more strongly by males are focused on repressing or denying unwanted ideas and affects (repression, suppression, denial, intellectualization) while establishing dominance or control (passive-aggression, omnipotence). However, for both factors, the number of defenses endorsed more strongly by one gender is offset by the number of defenses endorsed more strongly by the other gender.

Contrary to our expectation, acting out did not show a gender difference. Examination of item content showed the items to be neutrally worded (“I do something without thinking”). Thus, males could view these items as referring to overtly destructive or aggressive activities, and females could view them as indicating activities that are less aggressive or are aimed at the self.

As expected, the use of defenses changed with age. For all of the factor 1 defenses, the change was in the expected direction, i.e., lower scores with greater age. Four of the seven defenses in factor 2 increased in magnitude with age, supporting findings from Vaillant’s work (4, 19). The two exceptions, altruism and idealization, which declined with age, may reflect the growing realism and loss of innocence of adulthood.

Satisfaction With Life

This study provides support for the validity of the REM-71 in that self-reported defense styles were associated significantly with self-reported psychosocial adjustment. In line with studies involving clinical rating of defenses (3, 4, 7, 8, 19), increased use of factor 1 defenses predicted less satisfaction in each domain of life, while use of factor 2 defenses predicted greater satisfaction.

Conclusions

Our study presents some limitations. Although the study group was large and heterogeneous, it included a disproportionate number of adolescents. To understand the exact timetable of defense development, further studies should include more children and adults. Studies using lengthier, standardized outcome measures of functioning would clarify the role of defensive structure in important areas of psychopathology. It is also apparent that further understanding of defenses should be based on a gender-specific model.

The present research has shown that the REM-71 is a cohesive, balanced, and valid tool for assessing defenses in youths and adults. There are some ambiguities in the instrument, but they are few and most likely will be resolved by increasing the size and diversity of the subject groups studied. Much of the utility of this instrument derives from its relationship to an impressive body of literature representing both prospective and intensive studies, which laid the groundwork for this expansion (3, 4, 7, 8, 15, 17–20, 23, 26). The REM-71 provides a tool to expand on this solid foundation.

|

|

|

|

Received April 23, 1998; revisions received June 28 and Oct. 6, 1999, and March 15, 2000; accepted March 23, 2000. From the Division of Child Psychiatry and Child Development, Stanford University School of Medicine. Address reprint requests to Dr. Steiner, Division of Child Psychiatry and Child Development, Stanford University School of Medicine, 401 Quarry Rd., Stanford, CA, 94305-5719; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grants to Dr. Steiner from the Eucalyptus Foundation and The California Wellness Foundation. The authors thank Drs. Shirley Feldman, Randolf Weingarten, and David Spiegel for their assistance in developing and testing the item pool.

1. Wieland CM: Idris und Zenide. Leipzig, Germany, bey Weidmanns Erben und Reich, 1768, p 103Google Scholar

2. Steiner H: Freud against himself. Perspect Biol Med 1979; 20:510–527Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Perry JC, Cooper S: What do cross-sectional measures of defense mechanisms predict? in Ego Mechanisms of Defense: A Guide for Clinicians and Researchers. Edited by Vaillant G. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1992, pp 195–216Google Scholar

4. Vaillant GE: Ego Mechanisms of Defense: A Guide for Clinicians and Researchers. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1992Google Scholar

5. Freud S: Inhibitions, symptoms and anxiety (1926 [1925]), in Complete Psychological Works, standard ed, vol 20. London, Hogarth Press, 1959, pp 77–175Google Scholar

6. Andrews G, Pollock C, Stewart G: The determination of defense style by questionnaire. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:455–460Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Erickson SJ, Feldman SS, Steiner H: Defense mechanisms and adjustment in normal adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:826–828Link, Google Scholar

8. Tuulio-Henriksen A, Poikolainen K, Aalto-Setaala T, Lonnqvist J: Psychological defense styles in late adolescence and young adulthood: a follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:1148–1153Google Scholar

9. Shaw R, Ryst E, Steiner H: Temperament as a correlate of adolescent defense mechanisms. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 1996; 27:105–114Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Thienemann M, Shaw R, Steiner H: Defense styles and family environment. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 1998; 28:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Araujo K, Ryst E, Steiner H: Adolescent defense style and life stressors. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 1999; 30:19–28Medline, Google Scholar

12. Steiner H: Defense styles in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 1990; 9:141–151Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Feldman S, Araujo K, Steiner H: Defense mechanisms in adolescents as a function of age, gender, and mental health status. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:1344–1354Google Scholar

14. Smith C, Nasserbakht A, Feldman S, Steiner H: Psychological characteristics and DSM-III-R diagnoses at six-year follow-up of adolescent anorexia nervosa. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1993; 32:1237–1245Google Scholar

15. Apter A, Gothelf D, Offer R, Ratzoni G, Orbach I, Tyano S, Pfeffer C: Suicidal adolescents and ego defense mechanisms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:1520–1527Google Scholar

16. Steiner H, Garcia I, Matthews Z: Post traumatic stress disorder in incarcerated juvenile delinquents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:357–365Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Cramer P: The Development of Defense Mechanisms. New York, Springer, 1991Google Scholar

18. Conte H, Apter A: The Life Style Index: a self-report measure of ego defenses, in Ego Defenses: Theory and Measurement. Edited by Conte H, Plutchik R. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1995, pp 179–201Google Scholar

19. Vaillant GE: Adaptation to Life. Boston, Little, Brown, 1977Google Scholar

20. Bond M, Gardner ST, Christian J, Sigal JJ: Empirical study of self-rated defense styles. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:333–338Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Steiner H, Feldman S: Two approaches to the measurement of adaptive style: comparison of normal, psychosomatically ill, and delinquent adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:180–190Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Erickson S, Feldman S, Steiner H: Defense reactions and coping strategies in normal adolescents. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 1997; 27:45–56Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Haan N: Coping and Defending. New York, Academic Press, 1977Google Scholar

24. Maccoby EE: Gender and relationships: a developmental account. Am Psychol 1990; 45:513–520Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Nolen-Hoeksema S: Sex Differences in Depression. Stanford, Calif, Stanford University Press, 1990Google Scholar

26. Hauser ST, Borman EH, Bowlds MK, Powers SI, Jacobson AM, Noam GG, Knoebber K: Understanding coping within adolescence: ego development and coping strategies, in Life-Span Developmental Psychology. Edited by Cummings EM, Greene A, Karraker K. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1991, pp 177–194Google Scholar

27. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS: Using Multivariate Statistics, 2nd ed. New York, HarperCollins, 1993Google Scholar

28. Master Index to SAS System Documentation for Personal Computers. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1987Google Scholar

29. Zwick WR, Velicer WF: Comparison of five rules for determining the number of components to retain. Psychol Bull 1986; 99:432–442Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Kerlinger FN: Foundations of Behavioral Research, 3rd ed. New York, Holt, Rinehart, Winston, 1973Google Scholar

31. Andreasen NC: Creativity and mental illness: a conceptual and historical overview, in Depression and the Spiritual in Modern Art: Homage to Miro. Edited by Schildkraut JJ, Otero A. New York, Wiley & Sons, 1996, pp 2–14Google Scholar

32. Bar-On D: Different types of denial account for short- and long-term recovery of coronary patients. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 1985; 22:155–172Medline, Google Scholar