Axis I Psychiatric Comorbidity and Its Relationship to Historical Illness Variables in 288 Patients With Bipolar Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Bipolar disorder often co-occurs with other axis I disorders, but little is known about the relationships between the clinical features of bipolar illness and these comorbid conditions. Therefore, the authors assessed comorbid lifetime and current axis I disorders in 288 patients with bipolar disorder and the relationships of these comorbid disorders to selected demographic and historical illness variables. METHOD: They evaluated 288 outpatients with bipolar I or II disorder, using structured diagnostic interviews and clinician-administered and self-rated questionnaires to determine the diagnosis of bipolar disorder, comorbid axis I disorder diagnoses, and demographic and historical illness characteristics. RESULTS: One hundred eighty-seven (65%) of the patients with bipolar disorder also met DSM-IV criteria for at least one comorbid lifetime axis I disorder. More patients had comorbid anxiety disorders (N=78, 42%) and substance use disorders (N=78, 42%) than had eating disorders (N=9, 5%). There were no differences in comorbidity between patients with bipolar I and bipolar II disorder. Both lifetime axis I comorbidity and current axis I comorbidity were associated with earlier age at onset of affective symptoms and syndromal bipolar disorder. Current axis I comorbidity was associated with a history of development of both cycle acceleration and more severe episodes over time. CONCLUSIONS: Patients with bipolar disorder often have comorbid anxiety, substance use, and, to a lesser extent, eating disorders. Moreover, axis I comorbidity, especially current comorbidity, may be associated with an earlier age at onset and worsening course of bipolar illness. Further research into the prognostic and treatment response implications of axis I comorbidity in bipolar disorder is important and is in progress.

Epidemiologic data indicate that the rates of substance use and anxiety disorders in persons with bipolar disorder are significantly higher than the rates of substance use and anxiety disorders in the general population (1–12). Clinical data suggest that bipolar disorder may also commonly co-occur with eating disorders (6, 13–16). Conversely, patients with substance use, anxiety, and eating disorders often have bipolar disorder (4, 5, 17–22). Although major depressive disorder is also associated with elevated rates of most of these axis I disorders, epidemiologic studies comparing the psychiatric comorbidity of the depressive and bipolar disorders have often found higher rates of substance use (3, 9), panic (7), and obsessive-compulsive (8) disorders in bipolar patients than in depressive patients.

Little is known about the relationships between bipolar disorder and the axis I psychiatric conditions with which it often co-occurs. For example, few studies have systematically examined rates of comorbid axis I disorders across different diagnostic subtypes of bipolar disorder (e.g., bipolar I versus bipolar II disorder) or the effects of axis I psychiatric comorbidity on the phenomenology, course, outcome, and treatment response of bipolar disorder. Preliminary data have suggested that axis I psychiatric comorbidity (e.g., the presence of a substance use or anxiety disorder) may be associated with more severe subtypes of bipolar disorder (i.e., bipolar I versus bipolar II disorder) (3), earlier age at onset of bipolar disorder (22), mixed or dysphoric rather than pure mania (15, 22, 23), higher rates of suicidality (7), poorer overall outcome (24–30), and less favorable response to lithium (22, 28, 30, 31). Other studies, however, describe findings inconsistent with these (7).

The Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network was established to advance the understanding of the long-term course and treatment of bipolar disorder (32). Toward this goal, we used DSM-IV criteria to assess systematically the comorbid lifetime and current axis I psychiatric disorders in the first 288 patients with bipolar I or II disorder who entered the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network. We hypothesized that nonbipolar axis I disorders would be highly prevalent in these patients and that the presence of these disorders would be associated with negative effects on the presentation and course of their bipolar disorder, as assessed by historical illness variables.

Method

The methods of the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network (32), along with the demographic and clinical features of the first 261 patients (33), are described in greater detail elsewhere. Patients with any type of bipolar disorder were recruited from private, academic, and community mental health clinic outpatient settings by referral and advertisement. These patients entered into the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network if they met the following inclusion criteria: 1) age at least 18 years; 2) DSM-IV diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, bipolar disorder not otherwise specified, or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type; 3) willingness and ability to perform prospective daily mood charting and attend monthly evaluation appointments; 4) willingness to be in some form of ongoing treatment with a psychiatrist and to consider possible entry into future clinical trials; and 5) provision of written informed consent after the study procedures had been fully explained. Patients were not paid for their participation.

The Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network protocol included an extensive baseline evaluation (32). This evaluation was typically conducted over several visits and included completion of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Patient Edition (SCID-P) (34) to establish the diagnosis of bipolar disorder, illness characteristics (e.g., bipolar disorder subtype and age at onset), and comorbid axis I disorder diagnoses. The evaluation also included completion of structured patient-rated and clinician-administered questionnaires to determine demographic (e.g., current annual income, current level of occupational functioning) and historical illness (e.g., age at onset of affective symptoms; history of dysphoric mania, psychosis, rapid cycling, and suicide attempts; course of illness; and family history of psychiatric illness) variables. The SCID-P and questionnaires were administered by highly trained clinical research assistants at the individual sites. All had received SCID-P training at their own sites as well as extensive training in the SCID-P and the other instruments at the NIMH site (32). This training was supervised by one of the investigators (G.S.L.). As part of their SCID-P training, every clinical research assistant viewed and rated four tapes of SCID-P interviews. Excellent interrater reliability was achieved for the diagnosis of bipolar disorder with an overall kappa score of 0.92.

In completing the SCID-P and questionnaires, the researchers obtained information from all sources available in addition to the patient interview, including medical records and interviews with family members and treating clinicians. Age at onset of bipolar and comorbid disorders was defined as the first time the patient met full DSM-IV criteria for the disorder.

For this study, only patients with bipolar I or II disorder were included in the analysis. In addition, only “core” DSM-IV substance use, anxiety, and eating disorders were considered as comorbid axis I disorders. DSM-IV not otherwise specified disorders and impulse control disorders not elsewhere classified, although assessed, were not included in the analysis.

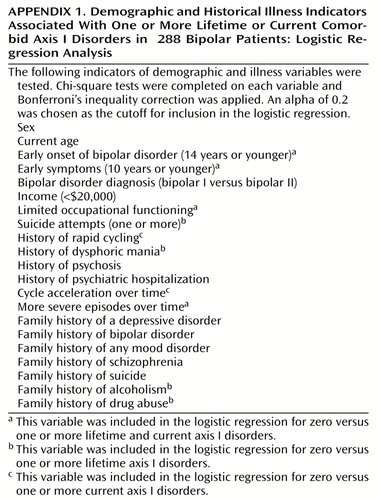

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS, version 8.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, 1997). Categorical variables were compared by using chi-square tests. Continuous variables were compared by using independent-sample or paired-sample t tests as appropriate. A Bonferroni inequality correction was applied to all variables significant at the p<0.05 level by chi-square or t test. To examine which historical illness variables were associated with lifetime and current comorbidity, a stepwise logistic regression was performed. An alpha of 0.2 was selected as the cutoff for inclusion in the regression.

Results

Two hundred eighty-eight patients with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder completed the SCID-P and the patient and clinician questionnaires. All patients were outpatients recruited from the community. One hundred twenty-six (44%) of the patients were men, the mean current age was 42.8 years (SD=11.3, range=19.1–81.9), the mean age at onset of illness was 22.3 (SD=10.4, range=1–57), and the mean duration of illness was 20.6 years (SD=12.2, range=0.1–54.8). One hundred sixteen (40%) of the patients reported limitation of occupational functioning by their bipolar illness, 205 (71%) reported one or more psychiatric hospitalizations, and 160 (56%) had a first-degree relative with a mood disorder. These features were highly similar to those of the first 261 Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network patients described in greater detail elsewhere (33).

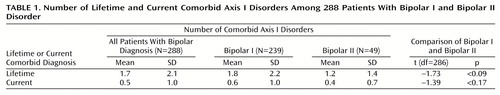

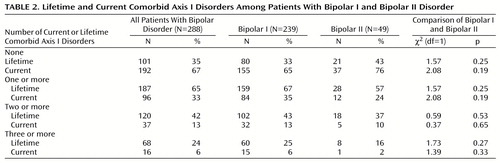

Table 1 shows that the lifetime DSM-IV axis I psychiatric comorbidity in this group of bipolar patients was high; patients met criteria for a mean of 1.7 (SD=2.1) lifetime nonbipolar axis I disorders. Current comorbidity was lower; patients met criteria for a mean of 0.5 (SD=1.0) current nonbipolar axis I disorders. Patients with bipolar I disorder did not differ from those with bipolar II disorder in their mean number of comorbid lifetime or current axis I disorders. As shown in Table 2, 187 (65%) of the patients met DSM-IV criteria for at least one lifetime comorbid disorder, and 96 (33%) met criteria for at least one current comorbid disorder. Sixty-eight (24%) patients had three or more lifetime disorders. Again, bipolar I and bipolar II patients showed no differences regarding rates of lifetime or current comorbid disorders.

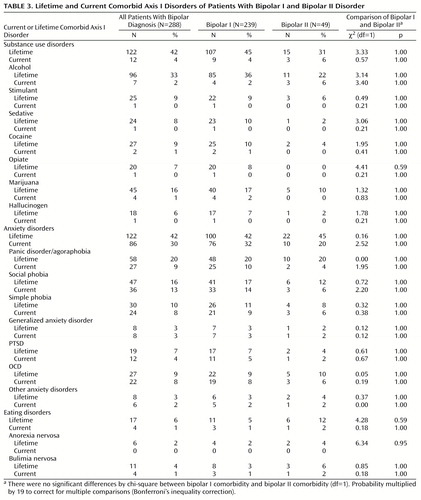

Table 3 displays the rates of specific comorbid lifetime and current axis I disorders in the entire group of patients and by bipolar subtype. Anxiety and substance use disorders were the most common comorbid lifetime disorders, followed by eating disorders, in all patients as well as in the bipolar I and II patients as separate groups. In addition, both as families of disorders and individually, substance use, anxiety, and eating disorders were equally common in patients with bipolar I and bipolar II disorders. Alcohol was the most commonly abused substance, and marijuana was the most commonly abused drug, followed by noncocaine stimulants, cocaine, and sedatives. Panic disorder/agoraphobia and social phobia were the two most common anxiety disorders. Bulimia nervosa was the most common eating disorder.

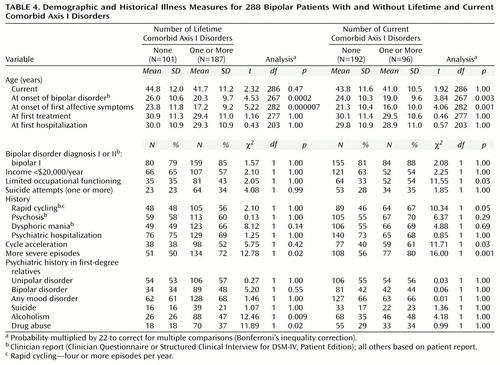

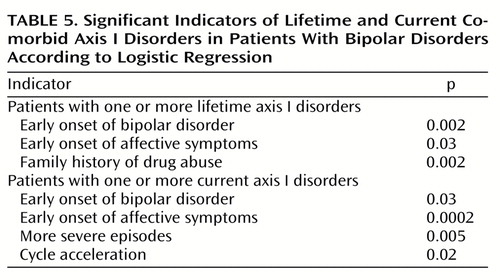

Table 4 shows the relationships between the presence and absence of at least one lifetime or current axis I disorder and selected demographic and historical illness variables. Lifetime axis I comorbidity was associated with early age at onset of first affective symptoms and bipolar disorder, development of more severe episodes over time, and family history of alcoholism and drug abuse. Current axis I comorbidity was associated with early age at onset of first affective symptoms and illness, limited occupational functioning, history of rapid cycling, and history of development of both cycle acceleration and more severe episodes over time. Appendix 1 lists the demographic and historical illness indicators associated with one or more lifetime or current comorbid axis I disorders entered into the regression analysis. As shown in Table 5, significant indicators for lifetime comorbidity by stepwise logistic regression were early onset of bipolar disorder, early onset of affective symptoms, and family history of drug abuse. Significant indicators for current comorbidity were again early onset of bipolar disorder and affective symptoms, as well as development of more severe episodes over time and cycle acceleration.

Discussion

Our findings of high rates of lifetime and current substance use, anxiety, and, possibly, eating disorders in outpatients with bipolar disorders are consistent with existing data from community (1–12) and clinical (4–6, 13–16, 22, 23, 28–30, 35–37) samples, suggesting that these disorders co-occur with bipolar disorder more often than expected by chance alone. Indeed, in our group, bipolar disorder was twice as likely to be accompanied by another lifetime axis I psychiatric disorder (N=187, 65%) than to exist by itself (N=101, 35%). Moreover, consistent with other findings, axis I comorbidity was associated with a more adverse onset and course of bipolar disorder (with earlier age at onset of affective symptoms and the bipolar disorder syndrome and higher rates of development of cycle acceleration and more severe episodes over time) (7, 14, 22–31).

These findings, however, must be considered in view of several methodological limitations. First, this study included only patients with bipolar disorder and lacked direct comparisons with a normal control group, another psychiatrically ill group, or an epidemiologic sample. Also, interviewers were not blind to the patients’ established diagnoses of bipolar disorder. The rates of comorbid axis I disorders found in our group might therefore be falsely elevated because of Berkson’s bias (38) or interviewer bias. In addition, historical illness variables reported here were obtained retrospectively, sometimes by self-report, and it is possible that patients with comorbid disorders were biased toward overreporting earlier age at onset and more severe course of their bipolar symptoms.

A second limitation is that our group of bipolar patients may not be representative of the disorder because of the inclusion criteria of the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network. Specifically, only outpatients willing to participate in research and to be compliant with treatment were included. Our results, therefore, might not be generalizable to other bipolar populations, including those who are hospitalized or those who are not in treatment. However, comparison of the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network bipolar patients with other clinical populations, including those of Winokur (39), the NIMH Collaborative Study (40), and the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association (41), reveals many similarities (33).

Another potential limitation is that there is considerable phenomenologic overlap among the manic, depressive, and mixed symptoms and episodes of bipolar disorder and other axis I disorders. Rates of certain axis I disorders might be falsely elevated because of misattribution of affective symptoms to these other disorders. Indeed, an important complication of studies of comorbidity in general is that as the number of recognized psychiatric diagnoses increases, rates of comorbidity increase as well (6).

Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths. First, to our knowledge, this is the largest cohort of individuals with bipolar disorder to have their comorbid axis I disorders systematically assessed with structured interviews. Epidemiologic studies assessing axis I comorbidity of patients with bipolar disorder have evaluated cohorts of 168 (3, 7, 8), 29 (10), and 99 (11) subjects, respectively. The largest clinical study assessing axis I comorbidity in bipolar patients (29) assessed comorbid substance abuse in 134 hospitalized bipolar I patients with a manic or mixed episode and found that 33% met criteria for an alcohol use disorder and 34% met criteria for a drug use disorder. Second, this is the first study to use DSM-IV criteria to diagnose both bipolar and comorbid axis I disorders. Third, patients were drawn from five different sites that were geographically diverse, including four sites in the United States and one site in Europe. Fourth, relationships among comorbidity and demographic and historical illness variables were systematically evaluated.

Our findings of high rates of substance use, anxiety, and, to a lesser degree, eating disorders in patients with bipolar disorder have several important clinical implications. The first is that a comprehensive evaluation of patients with bipolar disorder should include a systematic search for and assessment of these and other comorbid disorders. Also, patients with uncomplicated bipolar disorder, especially children, adolescents, and young adults, need to be observed carefully for the development of other axis I disorders and educated about their risk for developing them. Conversely, patients presenting with multiple axis I disorders should be carefully evaluated for the development of mood disorders, especially bipolar disorder. Second, in young people with a family history of bipolar disorder, the emergence of an early-onset anxiety, substance use, or eating disorder should trigger consideration of a prodromal mood disorder, including a bipolar disorder. Third, our findings that axis I psychiatric comorbidity may be associated with earlier age at onset and development of cycle acceleration and more severe episodes over time—clinical features of bipolar disorder that themselves have been associated with more severe illness or poorer outcome—suggest that bipolar disorder with a comorbid axis I disorder should be carefully and ultimately perhaps differentially managed.

Our data, however, do not permit conclusions regarding the comparative treatment of bipolar patients with and without various comorbid axis I disorders. To our knowledge, no large, prospective, controlled studies have assessed the effects of treating different comorbid disorders on the outcome of bipolar disorder or compared the efficacy of different mood-stabilizing agents in bipolar patients with selected comorbid disorders. Such prospective data are necessary to determine whether differential treatment based on comorbidity improves the outcome of bipolar disorder. Nonetheless, consideration of axis I comorbidity in bipolar disorder might represent yet another clinically useful way of characterizing or subtyping the illness. Furthermore, greater attention should be focused on the efficacy of agents with antimanic or mood-stabilizing properties in the treatment of pathological substance use, anxiety, and eating syndromes.

How might the extensive overlap of bipolar disorder with these other axis I disorders be explained? One possibility is that these disorders are in fact distinct but unrelated disease entities, representing either risk factors for each other or the sharing of similar end states from different etiologic mechanisms. This possibility is supported in part by the findings of high rates of substance use disorders in the families of patients with comorbid substance use disorder, suggesting the inheritance of two (or more) illnesses in some patients. Another possibility, however, is that bipolar disorder is related to substance use, anxiety, and eating disorders (or at least some forms of these disorders) and, by extension, that all of these disorders may be related to one another and share a common underlying pathophysiologic etiology (8). This possibility is supported by three large-scale epidemiologic studies indicating that mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders are highly comorbid with one another (3, 9, 11, 42). It is also supported by a growing body of research suggesting that substance use, anxiety, and eating disorders may be associated with elevated familial rates of mood disorders and may respond to agents with thymoleptic (antidepressant and/or mood-stabilizing) properties (21, 43). Indeed, preliminary research indicates that dysregulation in several common neurotransmitter systems—including the dopaminergic, serotonergic, noradrenergic, and γ-aminobutyric-acid-ergic—may be important in the pathophysiology of all of these disorders (4, 44, 45). Further research examining the overlap of these disorders would therefore appear to be just as important as further research into their differences.

In sum, our findings are consistent with others suggesting that bipolar disorder is more often than not accompanied by other axis I disorders. Moreover, axis I comorbidity may be associated with clinical features that themselves have been associated with greater severity and/or poorer outcome of bipolar disorder. In subsequent work, we will extend these observations to the impact of axis I comorbidity on the prospectively evaluated course of illness and differential response to treatment of bipolar disorder.

|

|

|

|

|

Received June 15, 1998; revisions received Dec. 23, 1999, and March 2, 2000; accepted March 24, 2000. From the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network, including the Biological Psychiatry Program, Department of Psychiatry, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine; the University of California, Los Angeles, Neuropsychiatric Institute and the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Los Angeles; the Southwest Medical Center at Dallas; the Biological Psychiatry Branch, NIMH, Bethesda, Md.; and the HC Rümke Group, Willem Arntsz Huis and Academic Hospital, Utrecht, the Netherlands. Address reprint requests to Dr. McElroy, Biological Psychiatry Program, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, P.O. Box 670559, 231 Bethesda Ave., Cincinnati, OH 45267-0559; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by the Theodore and Vada Stanley Foundation.

|

Appendix 1

1. Boyd JH, Burke JD, Gruenberg E, Holzer LE III, Rae DS, George LK, Karno M, Stoltzman T, McEvoy L, Nestadt G: Exclusion criteria of DSM-III: a study of co-occurrence of hierarchy free syndromes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:983–989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Helzer J, Pryzbeck T: The co-occurrence of alcoholism with other psychiatric disorders in the general population and its impact on treatment. J Stud Alcohol 1988; 49:219–224Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Goodwin FK: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. JAMA 1990; 264:2511–2518Google Scholar

4. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR: Manic-Depressive Illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990Google Scholar

5. Brady KT, Lydiard RB: Bipolar affective disorder and substance abuse. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1992; 12(suppl 1):17–22Google Scholar

6. Strakowski SM, McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, West SA: The co-occurrence of mania with medical and other psychiatric disorders. Int J Psychiatry Med 1994; 24:305–328Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Chen Y-W, Dilsaver SC: Comorbidity of panic disorder in bipolar illness: evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:280–282Link, Google Scholar

8. Chen Y-W, Dilsaver SC: Comorbidity for obsessive-compulsive disorder in bipolar and unipolar disorders. Psychiatry Res 1995; 59:57–64Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Edlund MJ, Frank RG, Leaf PJ: The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: implications for prevention and service utilization. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1996; 66:17–31Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Kessler RC, Rubinow DR, Holmes C, Abelson JM, Zhao S: The epidemiology of DSM-III-R bipolar I disorder in a general population survey. Psychol Med 1997; 27:1079–1089Google Scholar

11. Ravelli A, Bijl RV, van Zessen G: Comorbiditeit van psychiatrische stoornissen in de Nederlandse bevolking: resultaten van de Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie 1988; 40:531–544Google Scholar

12. Szádóczky E, Papp ZS, Vitrai J, Ríhmer Z, Füredi J: The prevalence of major depressive and bipolar disorders in Hungary: results from a national epidemiologic survey. J Affect Disord 1998; 50:153–162Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Strakowski SM, Tohen M, Stoll AL, Faedda GL, Goodwin DC: Comorbidity in mania at first hospitalization. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:554–556Link, Google Scholar

14. Strakowski SM, Tohen M, Stoll AL, Faedda GL, Mayer PV, Kolbrener ML, Goodwin DC: Comorbidity in psychosis at first hospitalization. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:752–757Link, Google Scholar

15. McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, Keck PE Jr, Tugrul KL, West SA, Lonczak HS: Differences and similarities in mixed and pure mania. Compr Psychiatry 1995; 36:187–194Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Kruger S, Shugar G, Cooke RG: Comorbidity of binge eating disorder and the partial binge-eating syndrome with bipolar disorder. Int J Eat Disord 1996; 19:45–52Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Savino M, Perugi G, Simonini E, Soriani A, Cassano GB, Akiskal HS: Affective comorbidity in panic disorder: is there a bipolar connection? J Affect Disord 1993; 28:155–163Google Scholar

18. Bowen R, South M, Hawkes J: Mood swings in patients with panic disorder. Can J Psychiatry 1995; 39:91–94Google Scholar

19. Hudson JI, Pope HG Jr, Yurgelun-Todd D, Jonas JM, Frankenburg FR: A controlled study of lifetime prevalence of affective and other psychiatric disorders in bulimic outpatients. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:1283–1287Google Scholar

20. Halmi KA, Eckert E, Marchi P, Sampugnaro V, Apple R, Cohen J: Comorbidity of psychiatric diagnoses in anorexia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:712–718Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Simpson SG, Al-Mufti R, Andersen AE, De Paulo JR: Bipolar II affective disorder in eating disorder inpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992; 180:719–722Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Sonne SC, Brady KT, Morton WA: Substance abuse and bipolar disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 1994; 182:349–352Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Himmelhoch JM, Garfinkel ME: Sources of lithium resistance in mixed mania. Psychopharmacol Bull 1986; 22:613–620Medline, Google Scholar

24. Black DW, Winokur G, Hulbert J, Nasrallah A: Predictors of immediate response in the treatment of mania: the importance of comorbidity. Biol Psychiatry 1988; 24:191–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Black DW, Winokur G, Bell S, Nasrallah A, Hulbert J: Complicated mania: comorbidity and immediate outcome in the treatment of mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:232–236Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Black DW, Hulbert J, Nasrallah A: The effect of somatic treatment and comorbidity on immediate outcome in manic patients. Compr Psychiatry 1989; 30:74–79Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Tohen M, Waternaux CM, Tsuang MT, Hunt AT: Four-year follow-up of twenty-four first-episode manic patients. J Affect Disord 1990; 19:79–86Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Young LT, Cooke RG, Robb JC, Leavitt AJ, Joffe RT: Anxious and non-anxious bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 1993; 29:49–52Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, West SA, Sax KW, Hawkins JM, Bourne ML, Haggard P: Twelve-month outcome of patients with bipolar disorder following hospitalization for a manic or mixed episode. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:646–652Link, Google Scholar

30. Goldberg JF, Garno JL, Leon AC, Kocsis JH, Portera L: A history of substance abuse complicates remission from acute mania in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:733–740Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. O’Connell RA, Mayo JA, Flatow L, Cuthbertson B, O’Brien BE: Outcome of bipolar disorder on long-term treatment with lithium. Br J Psychiatry 1991; 159:123–129Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Leverich GS, Nolen W, Rush AJ, McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, Denicoff RD, Suppes T, Altshuler LL, Kupka R, Frye MA, Kramlinger KG, Post RM: The Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network, I: longitudinal methodology. J Affect Disord (in press)Google Scholar

33. Suppes T, Leverich GS, Keck PE Jr, Nolen WA, Denicoff KD, Altshuler LL, McElroy SL, Rush AJ, Kupka R, Frye MA, Bickel M, Post RM: The Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network, II: demographics and illness characteristics of the first 261 patients. J Affect Disord (in press)Google Scholar

34. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P), version 2. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

35. Winokur G, Coryell W, Akiskal HS, Maser JD, Keller MB, Endicott J, Mueller T: Alcoholism in manic-depressive (bipolar) illness: familial illness, course of illness, and the primary-secondary distinction. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:365–372; correction, 152:1106Google Scholar

36. Krüger S, Cooke RG, Hasey GM, Jorna T, Persad E: Comorbidity of obsessive-compulsive disorder in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 1995; 34:117–120Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Pini S, Cassano GB, Simirno M, Russo A, Montgomery SA: Prevalence of anxiety disorders comorbidity in bipolar depression, unipolar depression and dysthymia. J Affect Disord 1997; 42:145–153Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Berkson J: Limitations of the application of fourfold table analysis to hospital data. Biometric Bulletin 1946; 2:47–53Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Winokur G: The Iowa 500: heterogeneity and course in manic-depressive illness (bipolar). Compr Psychiatry 1975; 16:125–131Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Katz MM, Secunda SK, Hirschfeld RMA, Koslow SH: NIMH Clinical Research Branch Collaborative Program on the Psychobiology of Depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979; 36:765–771Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Lish JD, Dime-Meenan S, Whybrow PC, Price RA, Hirschfeld RMA: The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association (DMDA) survey of bipolar members. J Affect Disord 1994; 31:281–294Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Hudson JI, Pope HG Jr: Affective spectrum disorder: does antidepressant response identify a family of disorders with a common pathophysiology? Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:552–564Google Scholar

44. Musselman DL, DeBattista C, Nathan KI, Kilts CD, Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB: Biology of mood disorders, in The American Psychiatric Press Textbook of Psychopharmacology, 2nd ed. Edited by Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1998, pp 549–588Google Scholar

45. Dilsaver SC: The pathophysiologies of substance abuse and affective disorders: an integrative model? J Clin Psychopharmacol 1987; 7:1–10Google Scholar