Are Suicide Attempters Who Self-Mutilate a Unique Population?

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Individuals who mutilate themselves are at greater risk for suicidal behavior. Clinically, however, there is a perception that the suicide attempts of self-mutilators are motivated by the desire for attention rather than by a genuine wish to die. The purpose of this study was to determine differences between suicide attempters with and without a history of self-mutilation. METHOD: The authors examined demographic characteristics, psychopathology, objective and perceived lethality of suicide attempts, and perceptions of their suicidal behavior in 30 suicide attempters with cluster B personality disorders who had a history of self-mutilation and a matched group of 23 suicide attempters with cluster B personality disorders who had no history of self-mutilation. RESULTS: The two groups did not differ in the objective lethality of their attempts, but their perceptions of the attempts differed. Self-mutilators perceived their suicide attempts as less lethal, with a greater likelihood of rescue and with less certainty of death. In addition, suicide attempters with a history of self-mutilation had significantly higher levels of depression, hopelessness, aggression, anxiety, impulsivity, and suicide ideation. They exhibited more behaviors consistent with borderline personality disorder and were more likely to have a history of childhood abuse. Self-mutilators had more persistent suicide ideation, and their pattern for suicide was similar to their pattern for self-mutilation, which was characterized by chronic urges to injure themselves. CONCLUSIONS: Suicide attempters with cluster B personality disorders who have a history of self-mutilation tend to be more depressed, anxious, and impulsive, and they also tend to underestimate the lethality of their suicide attempts. Therefore, clinicians may be unintentionally misled in assessing the suicide risk of self-mutilators as less serious than it is.

Self-mutilation is deliberate self-harm without the intent to die. The most usual forms are cutting and burning (1, 2). Individuals with borderline personality disorder who have a history of self-mutilation are at much greater risk of death by suicide. Self-mutilation occurs most often in the context of borderline personality disorder (3), which carries a lifetime suicide rate of 5%–10% (4–6). Approximately 55%–85% of self-mutilators have made at least one suicide attempt (7–12). Despite these substantial morbidity and mortality rates, the purpose of suicidal behavior in these individuals has been described as not “genuinely” suicidal or life-threatening (13) but primarily attention-seeking and manipulative. However, it is questionable to view this behavior as nonserious because up to 10% of this population commits suicide. One possibility is that suicidality in the context of borderline personality disorder and self-mutilation simply presents a different clinical picture but results in its seriousness being underestimated by some mental health professionals.

Self-mutilation is characterized typically by a sense of rising tension before the act and preoccupation with strong and persistent urges to hurt oneself (14). At some point, the urge becomes overwhelming, the individual is no longer able or willing to resist, and he or she then engages in self-mutilation. The self-mutilator reports a range of motivations, including self-punishment, tension reduction, improvement in mood, and distraction from intolerable affects (1, 2). Following the act, the individual usually reports feeling better and relieved (1, 2, 12, 15).

Suicidal feelings are not usually characterized in this manner. Feelings of hopelessness, despair, and depression predominate (16). It is possible, however, that there is a subtype of suicidal behavior that has death as its intent but is experienced emotionally and cognitively as a pattern similar to that of episodes of self-mutilation. This notion extends and modifies our conceptualization (8) and that of Linehan (17), who postulated that all deliberate self-harm ought to be considered on a continuum of lethality, regardless of the intention to die. In our conceptualization, suicidal behavior is considered distinct from self-mutilation in its intent but may share common experiential qualities. If our concept is valid, it might be more effective to treat suicidal behavior in self-mutilating patients in the same way that self-mutilatory behavior is addressed. This would likely lead to a different approach from that taken when suicidal behavior is a manifestation of depression, where treating the mood disorder reduces the risk of suicidal behavior.

The current study compares the suicidal behavior of suicide attempters with a cluster B personality disorder who had a history of self-mutilation with the suicidal behavior of suicide attempters with a cluster B personality disorder who had no history of self-mutilation. The purposes of this study were 1) to compare suicide attempters with cluster B personality disorders who did or did not have a history of self-mutilation to determine whether self-mutilating suicide attempters differ clinically from attempters who do not mutilate themselves and 2) to determine whether the characteristics of the suicide attempts of self-mutilators differ from the attempts of those who do not mutilate themselves. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare self-mutilating suicide attempters with a diagnostically matched group of suicide attempters with no history of self-mutilation. The results of this study may aid the clinician in evaluating suicidal potential in a group of patients who are difficult to assess and treat.

Method

Subjects

Fifty-three psychiatric patients who had a history of at least one suicide attempt and a DSM-III-R diagnosis of a cluster B (i.e., borderline, antisocial, narcissistic, or histrionic) personality disorder participated in this study. Exclusion criteria included current substance abuse or dependence, history of head trauma resulting in coma, and mental retardation or other substantial cognitive impairment that interfered with the patient’s ability to be interviewed and to complete rating scales. The study was approved by the institutional review board of our facility, and all subjects gave written informed consent.

The 53 patients had a mean age of 29.9 years (SD=10, range=18–65); most were female (N=42, 79%), Caucasian (N=47, 89%), single (N=37, 70%), without children (N=43, 81%), and unemployed (N=35, 66%). Forty (75%) of the patients had attended college; of these, 11 completed college and seven completed graduate school. Fifty (94%) of the subjects were diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, three subjects (6%) had other types of cluster B personality disorders (one each was antisocial, histrionic, or narcissistic), and 35 (66%) had comorbid major depression.

All patients had a history of at least one suicide attempt; the mean lifetime number was 3.0 attempts (SD=2.4). The study group was divided into two subgroups according to the presence or absence of a history of nonsuicidal self-mutilation, i.e., any purposeful self-harm, committed without intent to die and resulting in tissue damage, most frequently cutting and burning. Self-mutilation was assessed by interview and rated on the Schedule for Interviewing Borderlines (18). Subjects with a history of self-mutilation and at least one suicide attempt made up the self-mutilation group (N=30), and those with at least one suicide attempt but without self-mutilation made up the group without self-mutilation (N=23).

Diagnostic and Behavioral Assessment

Suicidality was rated on several clinician-administered scales and by taking an extensive suicide history. The Suicide Intent Scale (19) is a 20-item scale that examines aspects of the subject’s most recent suicide attempt bearing on the seriousness of the intent to die. The Scale for Suicide Ideation (20) is a 19-item scale that assesses thoughts, feelings, and plans regarding suicide. Patients were assigned DSM-III-R diagnoses following interviews, with a trained clinician, that included the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (21), the Schedule for Interviewing Borderlines (18), and a clinical interview to add the required information for converting Research Diagnostic Criteria diagnoses into DSM-III-R diagnoses.

Aggression was assessed by using a 10-item semistructured interview modified from the Brown-Goodwin Lifetime Aggression Scale (22); this interview evaluated the history of aggressive behavior in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. An additional measure of aggression was the Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (23), which includes subscales of assault, irritability, resentment, indirect hostility, negativism, suspiciousness, verbal hostility, and guilt.

Depressive symptoms were measured with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (24) and the Beck Hopelessness Scale (25). The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (26) was also administered to assess current psychotic symptoms. Information on physical and sexual childhood abuse was obtained by using a semistructured clinical interview.

Data Analysis

Two-tailed Student’s t tests for continuous variables and chi-square analysis for categorical variables were used to compare the groups of patients with and without a history of self-mutilation on demographic, behavioral, and psychopathology measures. Results are reported as means and standard deviations unless otherwise indicated.

Results

Demographic Comparisons

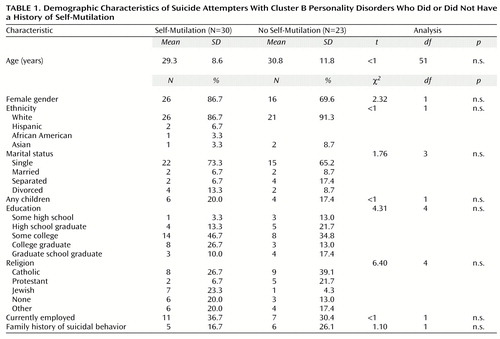

The groups of subjects with and without a history of self-mutilation did not differ by age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, religious affiliation, education level, or employment rate (Table 1). The rate of current major depression did not differ between the groups (data not shown). Seventeen percent of the self-mutilation group and 26% of the group without self-mutilation had a family history of either suicide attempts or completed suicide in first-degree relatives (Table 1).

The number of psychiatric hospitalizations in each group was not significantly different (mean=3.1, SD=3.8, for self-mutilators; mean=3.0, SD=3.0, for those with no self-mutilation) (t<1, df=49, n.s.). There were no significant differences in the proportion of subjects with a history of receiving psychotherapy (27 [90%] of self-mutilators compared with 17 [74%] of those with no self-mutilation) (χ2=2.47, df=1, n.s.).

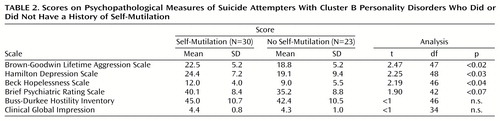

Aggression and Abuse History

The self-mutilation group tended to be more aggressive, with significantly higher scores on the Brown-Goodwin Lifetime Aggression Scale (Table 2). With respect to hostility, the self-mutilation group did not have significantly higher Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory scores (Table 2). The only Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory subscale score reaching significance was the irritability subscale (mean=8.2, SD=1.8, for those with self-mutilation compared with mean=6.6, SD=2.9, for those without self-mutilation) (t=2.42, df=47, p<0.02).

The self-mutilation group reported significantly greater frequency of physical punishment during childhood (t=2.19, df=27, p<0.04) but did not report more frequent sexual abuse. Ratings of severity of physical abuse were not significantly different between groups (mean=1.8, SD=1.2, for those with self-mutilation compared with mean=1.1, SD=1.3, for those without self-mutilation) (t=1.73, df=31, p<0.10).

Psychopathology

Psychopathology comparisons are presented in Table 2. The self-injurious patients were more depressed according to their scores on the Hamilton depression scale. Two subscales differentiated the groups: the self-mutilation group scored higher on the anxiety and somatic subscale and the cognition disturbance subscale (data not shown). However, the frequency of a current major depressive episode was similar in the groups: 70% (N=21) of those with and 61% (N=14) of those without a history of self-mutilation (data not shown). Thus, both groups had high rates of major depression, but the depression of the subjects with a history of self-mutilation was more severe. Furthermore, these subjects also scored significantly higher on the Beck Hopelessness Scale (Table 2).

The groups did not differ on Clinical Global Impression scores, and the self-mutilation group had nonsignificantly higher BPRS scores (Table 2). However, consistent with the Hamilton depression scale findings, the self-mutilation group obtained higher scores on the BPRS subscale of anxiety and depression (data not shown).

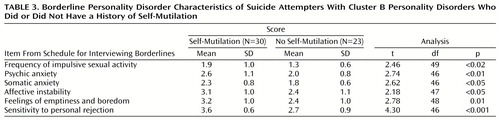

The self-mutilation group scored significantly higher on several items from the Schedule for Interviewing Borderlines (18): frequency of impulsive sexual activity, psychic anxiety, somatic anxiety, affective instability, feelings of emptiness and boredom, and sensitivity to personal rejection (Table 3). Thus, although almost all of the patients in both groups had borderline personality disorder, the self-mutilation group demonstrated more severe borderline pathology.

Characterization of Suicidal Behavior and Ideation

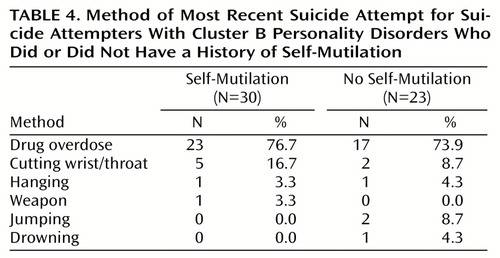

Important differences emerged between the groups in suicidality (Table 4). Despite the fact that all of the patients in one group had cut and/or burned themselves in nonsuicidal behavior (data not shown), the majority of the patients in both groups (77% and 74%) used pills when they attempted suicide. The second most frequent method was cutting; the self-mutilation group used this method almost twice as frequently (17% compared with 9%). Group membership did not predict whether the most recent attempt was violent or nonviolent or whether it was impulsive or planned (data not shown).

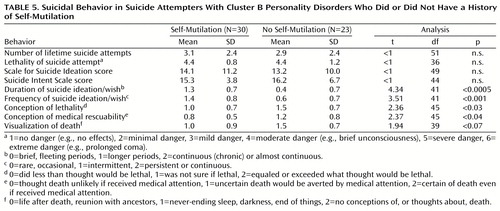

The groups did not differ in number of lifetime suicide attempts (Table 5), time since last attempt (data not shown), and total Scale for Suicide Ideation and Suicide Intent Scale scores (Table 5). Both groups had an average of three lifetime attempts, and the lethality of their attempts was relatively serious (e.g., brief periods of unconsciousness, moderate overdoses) (Table 5).

Although the groups did not differ in the actual lethality of their attempts, the self-mutilation group misperceived the severity of their attempts. When compared with the patients without self-mutilation, the self-injurious patients believed that their equally lethal attempts would be less likely to result in death (Table 5). The self-injurious patients also believed more strongly that they would be rescued, that death would be less likely if they received medical attention, and that death was a sleep-like state or a reunion with their ancestors (Table 5).

Although Scale for Suicide Ideation and Suicide Intent Scale scores did not differ between the groups, the self-mutilating patients experienced longer periods of suicidal ideation and more frequent ideation than those with no self-mutilation and tended to be more sure of their courage or competence to carry out an attempt.

Discussion

We found that the number of suicide attempts did not differ between patients with and without a history of self-mutilation, nor did the severity of suicidal ideation and the lethality of attempts. If self-mutilating suicide attempters made more frequent trivial attempts that were manipulative and attention-seeking, we would have expected to find that their attempts were less lethal. This was not the case.

Furthermore, our results suggest that this group is particularly disturbed and may be at greater risk for suicide for several reasons: 1) They experience more feelings of depression and hopelessness. 2) They are more aggressive and display more of the borderline personality disorder characteristics related to affective instability. 3) They underestimate the lethality of their suicidal behavior, believe that they will be rescued after an attempt, and view death with less finality. 4) They are troubled by suicidal thoughts for longer and more frequent periods of time.

Although the patients who mutilated themselves were more prone to experience feelings of depression, vegetative signs associated with mood disturbance were not different between the groups. These findings extend the work of Mann et al. (27) in the development of a model to predict suicidal behavior. Mann et al. found that the subjective experiences of depression and hopelessness differentiated attempters from nonattempters. Our study identifies a subgroup of attempters who are more prone to hopelessness and subjective depression and, therefore, may be at greater risk for ultimately committing suicide.

Self-mutilating suicide attempters have a history of childhood abuse, show more aggressive behavior, and have more evidence of borderline characteristics relating to affective instability and difficulties with interpersonal relationships. These factors increase the risk of suicide and suicide attempts (4, 14, 27). In the stress-diathesis model of suicidal behavior (27), aggression/impulsivity was the factor that most strongly distinguished between attempters and nonattempters. Again, as with depression and hopelessness, our findings identify a subgroup of suicide attempters who exhibit these behaviors more often than other attempters. Self-mutilating suicide attempters also displayed greater affective instability coupled with a sense of emptiness, sensitivity to personal rejection, and impulsive sexual activity. These findings suggest that self-mutilators may tend to rely on external sources for the regulation of internal states not just by engaging in self-injury but also in their relationships (5, 11, 16, 28). If the termination of a relationship is also the loss of a means of affect regulation, it is more understandable why this loss can lead to suicidal behavior.

It is interesting to note that the lethality of the suicide attempts in the self-mutilating group was as serious as that of their non-self-mutilating counterparts. Both groups had moderately severe attempts. This casts doubt on the clinical notion that the suicide attempts of self-mutilators represent attempts to seek attention and do not have to be treated with the same seriousness as the attempts of other patients. Furthermore, self-mutilators tend to underestimate the lethality of their attempts and do not seem to take the idea of death as seriously (e.g., they tend to view it as an opportunity for reunion or as a sleep-like state). Therefore, they might unwittingly minimize the seriousness of their suicidality to clinicians who, in turn, make judgments on the basis of the patients’ misreports.

Another possible consequence of self-mutilators’ underestimates of the lethality of their suicide attempts is that they may be more likely to die by mistake. In other words, self-mutilators believing that they are making a nonlethal attempt may die because they tend to misperceive lethality.

With respect to suicide ideation, the self-mutilators experienced more frequent and more persistent ideation than members of the group without self-mutilation. Thus, although the intensity of the ideation did not differ between the groups as measured by the Scale for Suicide Ideation, the self-mutilators seemed to live more of their lives plagued by suicidal thoughts. In this way, suicidality in this group may be similar to self-mutilation urges. Patients with a history of self-mutilation spend a substantial amount of time fighting off the urge to injure themselves (12). It may be that for this population, suicide attempts have a pattern similar to self-mutilation episodes in which there is an increasing urge and preoccupation leading to a temporary sense of relief following the behavior. This may help explain why these patients are no longer upset when they are hospitalized following a suicide attempt.

It is important to note that the differences we found could not be attributed to the presence or absence of a diagnosis of personality disorder. All patients in our study had a cluster B personality disorder, and all but three had borderline personality disorder. This reinforces the notion that there is something specific to self-mutilators that alters their experience of suicidal feelings and thoughts.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that clinicians should be careful not to discount the suicide attempts of patients with a history of self-mutilation despite the fact that the attempts resemble extreme self-injury. The tendency for clinicians to respond with aversion to self-mutilators may contribute to the misperception of risk in this population. Further, clinicians should be aware that the patients themselves may misinterpret the lethality of their attempts and may be unaware of the likelihood of death.

|

|

|

|

|

Received April 18, 2000; revision received July 26, 2000; accepted Oct. 12, 2000. From the Mental Health Clinical Research Center for the Study of Suicidal Behavior, Department of Neuroscience, New York State Psychiatric Institute; and the Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians & Surgeons, Columbia University, New York. Address reprint requests to Dr. Stanley, Department of Neuroscience, Unit 42, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1051 Riverside Dr., New York, NY 10032; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by NIMH grants MH-41847 and MH-46745.

1. Herpertz S: Self-injurious behavior: psychopathological and nosological characteristics in subtypes of self-injurers. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1995; 91:57–68Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Favazza AR: Repetitive self-mutilation. Psychiatr Annals 1992; 22(2):60–63Google Scholar

3. Langbehn DR, Pfohl B: Clinical correlates of self-mutilation among psychiatric inpatients. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1993; 5:45–51Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Fyer MR, Frances AJ, Sullivan T, Hurt SW, Clarkin J: Suicide attempts in patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:737–739Link, Google Scholar

5. Frances A, Fyer M, Clarkin J: Personality and suicide, in Psychobiology of Suicidal Behavior. Edited by Mann JJ, Stanley M. New York, New York Academy of Sciences, 1986, pp 281–293Google Scholar

6. Stone M, Hurt S, Stone D: The PI 500: long-term follow-up of borderline inpatients meeting DSM-III criteria, I: global outcome. J Personal Disord 1987; 1:291–298Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Dulit RA, Fyer MR, Leon AC, Brodsky BS, Frances AJ: Clinical correlates of self-mutilation in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1305–1311Google Scholar

8. Stanley B, Winchel R, Molcho A, Simeon D, Stanley M: Suicide and the self-harm continuum: phenomenological and biochemical evidence. Int Rev Psychiatry 1992; 4:149–155Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Roy A: Self-mutilation. Br J Med Psychol 1978; 51:201–203Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Rosenthal RJ, Rinzler C, Walsh R, Klausner E: Wrist-cutting syndrome: the meaning of a gesture. Am J Psychiatry 1972; 128:1363–1368Google Scholar

11. Gardner AR, Gardner AJ: Self-mutilation, obsessionality and narcissism. Br J Psychiatry 1975; 127:127–132Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Favazza AR, Conterio K: Female habitual self-mutilators. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1989; 79:283–289Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Bongar B, Peterson LG, Golann S, Hardiman JJ: Self-mutilation and the chronically suicidal patient: an examination of the frequent visitor to the psychiatric emergency room. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1990; 2:217–222Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Gardner DL, Cowdry RW: Suicidal and parasuicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1985; 8:389–403Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Kemperman I, Russ MJ, Shearin E: Self-injurious behavior and mood regulation in borderline patients. J Personal Disord 1997; 11:146–157Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Fawcett J, Scheftner W, Clark D, Hedeker D, Gibbons R, Coryell W: Clinical predictors of suicide in patients with major affective disorders: a controlled prospective study. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:35–40Link, Google Scholar

17. Linehan M: Suicidal people: one population or two? Ann NY Acad Sci 1986; 487:16–33Google Scholar

18. Baron M: The Schedule for Interviewing Borderlines. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1980Google Scholar

19. Beck AT, Schuyler D, Herman I: Development of suicidal intent scales, in The Prediction of Suicide. Edited by Beck AT, Resnick HLP, Lettieri DJ. Bowie, Md, Charles Press, 1974, pp 45–58Google Scholar

20. Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A: Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol 1979; 47:343–352Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Spitzer RL, Endicott J: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS), 3rd ed. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1978Google Scholar

22. Brown GL, Goodwin RK, Ballenger JC, Goyer PF, Major LF: Aggression in humans correlates with cerebrospinal fluid amine metabolites. Psychiatry Res 1979; 1:131–139Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Buss AH, Durkee A: An inventory for assessing different kinds of hostility. J Consult Psychol 1957; 21:343–349Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 180–192Google Scholar

25. Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L: The measurement of pessimism: the Hopelessness Scale. J Consult Clin Psychol 1974; 42:861–865Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 158–169Google Scholar

27. Mann JJ, Waternaux C, Haas GL, Malone KM: Toward a clinical model of suicidal behavior in psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:181–189Abstract, Google Scholar

28. Soloff PH, Lis JA, Kelly T, Cornelius J, Ulrich R: Self-mutilation and suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. J Personal Disord 1994; 8:257–267Crossref, Google Scholar