Pindolol Potentiation of Paroxetine for Generalized Social Phobia: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The effectiveness of pindolol as an adjunctive treatment to boost response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in patients with generalized social phobia was tested. METHOD: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover design was used to compare addition of 5 mg of pindolol t.i.d. or placebo for 4 weeks to a steady paroxetine dose. Subjects were 14 patients with generalized social phobia who were less than “very much improved” on the Clinical Global Impression scale after at least 10 weeks of treatment with a maximally tolerated dose of paroxetine. Changes on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale and the Social Phobia Inventory scores were compared across the two crossover periods. RESULTS: Pindolol was not significantly superior to placebo for augmenting the effects of paroxetine on social anxiety symptoms. None of the 14 subjects was deemed a responder to the pindolol arm of the crossover. CONCLUSIONS: Pindolol was no more effective than placebo in augmenting the effects of SSRI treatment for generalized social phobia.

Social phobia (also known as social anxiety disorder) is a prevalent, often functionally impairing condition (1). The more pervasive form of the illness, generalized social phobia, is associated with the greatest disability (2), with impairment escalating as the number of feared social situations increases (3). Generalized social phobia has recently been shown to be responsive to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), marking an important advance in the treatment of this condition (4–7). These studies show, however, that response rates to SSRIs in generalized social phobia peak at 50%–60%; even fewer patients (20%–30%) experience improvement that could be characterized as remission. Consequently, a role exists for adjunctive treatments that might further improve outcomes. An open-label trial of buspirone augmentation of SSRIs in social phobia suggested that it might be effective for this purpose (8), although to our knowledge no controlled trial has yet been conducted to confirm this finding.

Our rationale for testing pindolol as an adjunct to SSRIs for social phobia was twofold. First, there is a long tradition of using β blockers to treat anxiety related to public speaking and other types of performance anxiety, both of which are encompassed by the social phobia diagnosis (9). It is less clear, however, that β blockers are effective for other forms of social phobia, particularly for generalized social phobia. In a landmark study comparing the monoamine oxidase inhibitor phenelzine to the β blocker atenolol, the latter proved ineffective as a monotherapy for patients with generalized social phobia (10). Atenolol also lacked efficacy in another study of social phobia, where it was no more effective than placebo (11). Still, these observations would not preclude the possibility that a β blocker might be effective as an adjunct to other therapies, such as an SSRI.

The second reason for studying pindolol was that in addition to being a β blocker, it has 5-HT1A autoreceptor antagonist properties (12) that have garnered it prominence as a possible adjunct to antidepressants in the treatment of major depression (13, 14). Although its usefulness to enhance the efficacy of SSRIs for depression is in doubt, pindolol has been shown to accelerate the response to SSRIs in some (15, 16), but not all studies (17, 18).

For these reasons, we hypothesized that pindolol would augment the effects of SSRI treatment in generalized social phobia. This double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study was designed to test this hypothesis. To our knowledge, this report describes the first double-blind, placebo-controlled study of an adjunctive pharmacologic treatment for social phobia.

Method

This study was approved by the Committee on the Use of Human Subjects of the University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine. All subjects provided informed written consent. Subjects were patients with a clinically predominant diagnosis of DSM-IV generalized social phobia (comorbid mood disorders were not exclusionary) who had less than an excellent (i.e., Clinical Global Impression [CGI] of change “very much improved”) response to 10 weeks of treatment with a maximum tolerated dose of the SSRI paroxetine. Of 31 patients for whom paroxetine treatment was started, six dropped out during open-label paroxetine treatment because of adverse events or unspecified reasons, two were considered responders to paroxetine and did not proceed further in the study, four were eligible but elected not to participate in the double-blind phase, and five dropped out after completing only one arm or less of the double-blind phase.

Subjects were randomly assigned to receive either 5 mg of pindolol t.i.d. or placebo for 4 weeks. The 4 weeks was followed by a 2-week taper period, then crossover to the other agent (i.e., either pindolol or placebo), 4 weeks of treatment with the other agent, followed by another 2-week taper period. The administration of pindolol or placebo was conducted under double-blind conditions. Eight subjects received pindolol during the first treatment period, and six received it during the second treatment period. Subjects continued to take their maximally tolerated, stable dose of paroxetine throughout the study. No other concurrent psychotropic medications or specific psychotherapies were permitted. Fourteen patients met entry criteria and completed both phases of the double-blind crossover.

Changes in scores on the clinician-rated Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (19) and self-rated Social Phobia Inventory (20) were compared across the two crossover periods, as was the number of responders in each period. Responders were identified by a CGI rating of change (21) as “very much improved” relative to the start of treatment. Change scores during each period on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale and Social Phobia Inventory were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) with treatment period as the repeated measure (22). Two-tailed tests were used; p values of <0.05 were deemed statistically significant.

Results

Before treatment with paroxetine, the mean Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale and Social Phobia Inventory scores of the 14 subjects who later went on to complete the double-blind crossover study were 79.7 (SD=23.9) and 36.6 (SD=9.6), respectively. After a minimum of 10 weeks (range=10–14 weeks; mode=10 weeks) of treatment with open-label paroxetine as described, the mean Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale and Social Phobia Inventory scores of the participants had been reduced to 53.8 (SD=16.9) and 26.6 (SD=9.2), respectively. The mean paroxetine dose before randomization was 46.4 mg/day (SD=8.4). At this point the subjects entered the double-blind crossover study.

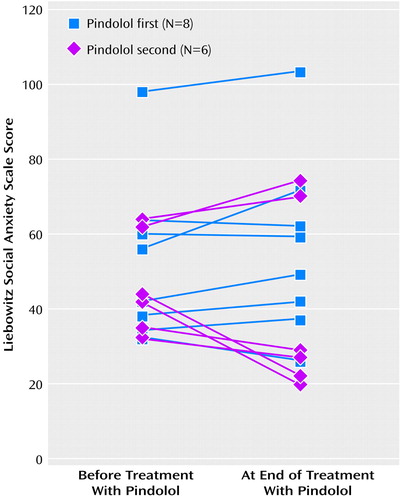

No carryover effect was detected on either the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale or the Social Phobia Inventory (F=0.96, df=1, 11, p>0.35, and F=0.88, df=1, 11, p>0.37, respectively). We therefore went on to test for period and treatment effects. No period (Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale: F=1.52, df=1, 11, p>0.24; Social Phobia Inventory: F=0.03, df=1, 11, p>0.86) or treatment (F=1.75, df=1, 11, p>0.21, and F=0.62, df=1, 11, p>0.45, respectively) effects were detected on either the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (Figure 1) or the Social Phobia Inventory. The power of this study to detect a drop of 10 points on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale was 70%; the power to detect a 15-point drop was 96%. Only one subject was considered a responder in either arm of the crossover. This subject became a responder while taking placebo; she subsequently became a nonresponder when crossed over to the pindolol arm.

Conclusions

Despite a dual rationale for hypothesizing that pindolol might be effective as an adjunct to SSRIs in the treatment of generalized social phobia, we found no evidence of its utility in this regard. There were no significant differences in social anxiety scores between the placebo and pindolol arms of this double-blind crossover study. Moreover, not a single subject converted to responder status while taking pindolol.

Recent in vivo neuroimaging work with a 5-HT1A radioligand suggests that the 2.5 mg t.i.d. dose of pindolol used in most depression studies may be too low to consistently augment the effects of SSRIs (23), and this explanation could possibly account for the negative results of this study. It is unclear whether our somewhat higher dose (5 mg t.i.d.) would be expected to be substantially more effective in this regard. Regardless, given the confluence of clinical data that pindolol probably does not enhance the response to SSRIs in depression—although it may accelerate response (15, 16)—its lack of efficacy in this study should not be altogether surprising. Irrespective of the explanation, the findings do underscore the lack of utility of β blockers for the treatment of generalized social phobia, either as monotherapy (as seen in other studies) or as an adjunct to SSRIs (as seen here) (10).

Treatments that can potentiate the effects of SSRIs for generalized social phobia are clearly needed. Pindolol does not appear to be useful for this purpose. Other treatments, both pharmacological and psychological, should be systematically tested under controlled conditions.

Received Oct. 25, 2000; revision received March 14, 2001; accepted April 19, 2001. From the Anxiety and Traumatic Stress Disorders Program, Department of Psychiatry, University of California San Diego. Address reprint requests to Dr. Stein, Department of Psychiatry (0985), University of California San Diego, 9500 Gilman Dr., La Jolla, CA 92093-0985; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by an investigator-initiated research grant from Glaxo SmithKline Pharmaceuticals. The authors thank Traci Bergthold, M.A., and Wanda Woten, R.N., for help with patient care and evaluation. Reena Deutsch, Ph.D., provided statistical consultation, which was supported by NIH General Clinical Research Center grant RR-00827.

Figure 1. Scores on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale of Subjects With Generalized Social Phobia Before and After Addition of Pindolol to a Steady Paroxetine Dose in a Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Studya

aNo significant effects of treatment with pindolol.

1. Stein MB, Kean Y: Disability and quality of life in social phobia: epidemiologic findings. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1606-1613Link, Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, Stein MB, Berglund P: Social phobia subtypes in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:613-619Link, Google Scholar

3. Stein MB, Torgrud LJ, Walker JR: Social phobia symptoms, subtypes and severity: findings from a community survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:1046-1052Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Stein MB, Liebowitz MR, Lydiard RB, Bushnell W, Gergel IP: Paroxetine treatment of generalized social anxiety disorder (social phobia): a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998; 280:708-713Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Baldwin D, Bobes J, Stein DJ, Scharwachter I, Faure M: Paroxetine in social phobia/social anxiety disorder—randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 175:120-126Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Stein MB, Fyer AJ, Davidson JRT, Pollack MH, Wiita B: Fluvoxamine treatment of social phobia (social anxiety disorder): a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:756-760Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Van Ameringen MA, Lane RM, Walker JR, Bowen RC, Chokka PR, Goldner EM, Johnston DG, Lavallee Y-J, Nandy S, Pecknold JC, Hadrava V, Swinson RP: Sertraline treatment of generalized social phobia: a 20-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:275-281Link, Google Scholar

8. Van Ameringen M, Mancini C, Wilson C: Buspirone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in social phobia. J Affect Disord 1996; 39:115-121Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Sutherland SM, Davidson JRT: β Blockers and benzodiazepines in pharmacotherapy, in Social Phobia: Clinical and Research Perspectives. Edited by Stein MB. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995, pp 323-346Google Scholar

10. Liebowitz MR, Schneier FR, Campeas R, Hollander E, Hatterer J, Fyer AJ, Gorman JM, Papp L, Davies S, Gully R, Klein DF: Phenelzine vs atenolol in social phobia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:290-300Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Turner SM, Beidel DC, Jacob RG: Social phobia: a comparison of behavior therapy and atenolol. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994; 62:350-358Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Blier P, Bergeron R, de Montigny C: Selective activation of post-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors induces rapid antidepressant response. Neuropsychopharmacology 1997; 16:333-338Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Blier P, Bergeron R: Effectiveness of pindolol with selected antidepressant drugs in the treatment of major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1995; 15:217-222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Blier P, Bergeron R: The use of pindolol to potentiate antidepressant medication. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(suppl 5):16-23Google Scholar

15. Zanardi R, Artigas F, Franchini L, Sforzini L, Gasperini M, Smeraldi E, Pérez J: How long should pindolol be associated with paroxetine to improve the antidepressant response? J Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 17:446-450Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Perez V, Gilaberte I, Faries D, Alvarez E, Artigas F: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pindolol in combination with fluoxetine antidepressant treatment. Lancet 1997; 349:1594-1597Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Berman RM, Darnell AM, Miller HL, Anand A, Charney DS: Effect of pindolol in hastening response to fluoxetine in the treatment of major depression: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:37-43Link, Google Scholar

18. Moreno FA, Gelenberg AJ, Bachar K, Delgado PL: Pindolol augmentation in treatment-resistant depressed patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:437-439Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Heimberg RG, Horner KJ, Juster HR, Safren SA, Brown EJ, Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR: Psychometric properties of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale. Psychol Med 1999; 29:199-212Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Connor KM, Davidson JR, Churchill LE, Sherwood A, Foa E, Weisler RH: Psychometric properties of the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN): a new self-rating scale. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176:379-386Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 218-222Google Scholar

22. Hills M, Armitage P: The two period crossover clinical trial. Br J Clin Psychiatry 1979; 8:7-20Google Scholar

23. Martinez D, Hwang D-R, Mawlawi O, Slifstein M, Kent J, Simpson N, Parsey RV, Hashimoto T, Huang Y, Shinn A, Van Heertum R, Abi-Dargham A, Caltabiano S, Malizia A, Cowley H, Mann JJ, Laruelle M: Differential occupancy of somatodendritic and postsynaptic 5HT1A receptors by pindolol: a dose-occupancy study with [11C]WAY 100635 and positron emission tomography in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 2001; 24:209-229Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar