Cortisol Activity and Cognitive Changes in Psychotic Major Depression

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The theory that psychotic major depression is a distinct syndrome is supported by reports of statistically significant differences between psychotic and nonpsychotic major depression in presenting features, biological measures, familial transmission, course and outcome, and response to treatment. This study examined differences in performance on a verbal memory test and in cortisol levels between patients with psychotic and nonpsychotic major depression and healthy volunteers. METHOD: Ten patients with psychotic major depression, 17 patients with nonpsychotic major depression, and 10 healthy volunteers were administered the Wallach Memory Recognition Test and had blood drawn at half-hour intervals over the course of an afternoon to assay cortisol levels. RESULTS: Subjects with psychotic major depression had a higher rate of errors of commission on the verbal memory test (incorrectly identified distracters as targets) than did subjects with nonpsychotic major depression or healthy volunteers; errors of omission were similar among the three groups. Subjects with psychotic major depression had higher cortisol levels throughout the afternoon than subjects with nonpsychotic major depression or healthy volunteers. This effect became even more pronounced later in the afternoon. CONCLUSIONS: Psychotic major depression is endocrinologically different from nonpsychotic major depression and produces cognitive changes distinct from those seen in nonpsychotic major depression.

There is mounting evidence to support the theory that psychotic major depression is a distinct syndrome. Statistically significant differences between psychotic and nonpsychotic major depression have been noted along many axes, including presenting features, biology, familial transmission, course and outcome, and response to treatment (1).

Other studies point to significant cognitive impairment in psychotic depression, compared to nonpsychotic depression. In an earlier study, we reported that patients with psychotic major depression demonstrated higher rates of dexamethasone nonsuppression and greater impairment on a variety of neuropsychological tests than did patients with nonpsychotic major depression (2). We hypothesized that cognitive deficits in psychotically depressed patients, and in some hypercortisolemic nonpsychotic depressed patients, reflected increased cortisol activity. More recently, several groups, including our own, have reported deficits in attention, response inhibition, and verbal memory in patients with psychotic major depression, compared to patients with nonpsychotic major depression (3–6). In a study comparing elderly patients with psychotic major depression to an age-matched group of patients with nonpsychotic major depression, the patients with psychotic major depression demonstrated significantly more perseverations on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, as well as greater prefrontal atrophy on structural magnetic resonance imaging scans (7).

Several studies have suggested that depressed patients with hypercortisolemia (or hypercortisoluria) and those who fail to suppress cortisol normally in response to dexamethasone show particularly pronounced cognitive deficits. For example, Rubinow et al. (8) observed a significant positive relationship between mean urinary free cortisol levels of depressed patients and the number of errors they made on the Halstead Category Test. A similar relationship was not observed for healthy comparison subjects. Furthermore, other studies have reported that depressed patients who do not suppress cortisol when given dexamethasone demonstrate greater cognitive deficits than do depressed patients who are able to suppress cortisol normally (9–12). The possible effects of psychosis have rarely been explored in these studies on cortisol activity.

How and where glucocorticoids may exert their effects on cognition has become a focus of investigation. Newcomer et al. (13, 14) reported that exogenous glucocorticoids impaired declarative memory and verbal memory in healthy adults. Wolkowitz et al. (15) noted that both depressed patients who were nonsuppressors on the dexamethasone suppression test and healthy volunteers given exogenous corticosteroids made significantly more errors of commission than omission on the Wallach Memory Recognition Test, a test of verbal memory. These studies suggest an effect on hippocampal-mediated verbal memory function. Sheline et al. (16) reported that total duration of depression was associated with impairment on verbal declarative memory tests and hippocampal atrophy. Although several of the patients in that study had received electroconvulsive therapy, the study did not address the possible effects of psychosis. In addition, although the authors noted that the hippocampal deficits could be related to elevated cortisol activity, no cortisol data were presented. Lupien et al. (17) reported that high doses of hydrocortisone impaired working memory, suggesting that glucocorticoids also exert effects on the prefrontal cortex. Data from this study, in conjunction with reports of prefrontal cortical impairment in psychotic major depression, suggest that this region could also play a role in the verbal memory deficits observed in psychotic major depression.

In this study we report the results of psychotic and nonpsychotic major depression patients on a verbal memory test. Our a priori hypotheses were that subjects with psychotic major depression would demonstrate 1) significantly greater afternoon cortisol levels than nonpsychotic major depression patients or healthy comparison subjects and 2) significantly greater errors of commission (but not omission) on a verbal memory test.

Method

Ten patients with psychotic major depression (six women, four men, mean age=46.9 years, SD=16.2, range=24–75), 17 patients with nonpsychotic major depression (seven women, 10 men, mean age=46.7 years, SD=12.7, range=28–70), and 10 healthy volunteers (five women, five men, mean age=44.9 years, SD=15.4, range=24–69) were tested. These groups did not differ significantly in age or gender. The study was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board, and all subjects gave written informed consent to participate. Subjects who used illicit drugs within the month before admission to the study or consumed ≥3 ounces of alcohol a day were excluded. In addition, patients with major medical illnesses, particularly endocrinopathies, were excluded, as were patients taking systemic steroids or antidepressant or antipsychotic medications. All subjects with psychotic major depression had not taken antipsychotic medication for at least 3 days before entry into the study. All subjects with psychotic and nonpsychotic major depression had taken no antidepressant medication for at least 1 week (5 weeks in the case of fluoxetine) before study entry. On the day before study entry, all participants were tested with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (18) and the vocabulary subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised (WAIS-R) (19). For patients with psychotic and nonpsychotic major depression, a minimum score of 21 on the Hamilton depression scale was required to enter the study.

At 10:00 a.m. on the day after qualifying for the study, each participant was administered the Wallach Memory Recognition Test (20). In this task, the subjects listened to a taped recording of a list of 16 words presented at the rate of one word every 10 seconds. The subject was instructed to repeat each of the 16 words and to consider what the words meant to them. After the list was presented, the subject participated in a 20-minute motor distraction task. The subject then listened to a 50-word list containing the 16 original target words and 34 distracter words and was asked to distinguish between the targets and the distracters. The target and distracter words were matched for frequency of written use and degree of imagery. Errors of omission occurred when the subject failed to identify a word from the original list. Errors of commission occurred when the subject falsely identified a distracter word as a word from the original list.

At 12:30 p.m., the subject was admitted to the Stanford University Medical Center’s Clinical Research Center. An intravenous line was started in one arm, and 5 cc of blood were drawn every half-hour beginning at 1:00 p.m. to assay cortisol levels (afternoon cortisol test) (21). Plasma was immediately separated from whole blood by centrifugation and then stored at –80°C before assay. Cortisol concentrations were measured by radioimmunoassay with a commercial kit from ICN Biomedicals (Costa Mesa, Calif.).

Cortisol levels, errors of omission, errors of commission, and WAIS vocabulary scores were compared across the three groups by using Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance, followed by Mann-Whitney U tests where appropriate. Significance levels for the Kruskal-Wallis test were approximated by using chi-square tests. Spearman rho correlation coefficients were used to measure the association between cortisol levels and cognitive performance. To describe the linear changes in cortisol levels across the seven time points in the afternoon cortisol test, regression lines were computed for each of the three groups. An alpha of 0.05 (two-tailed) was used as the threshold for determining statistical significance.

Results

Significant differences were not observed among the three groups on the WAIS vocabulary test scores (comparison subjects: mean=55.90, SD=3.36; patients with nonpsychotic major depression: mean=56.00, SD=2.83; patients with psychotic major depression: mean=47.10, SD=5.10) (χ2=1.60, df=2, p=0.19). On the Wallach Memory Recognition Test, the total number of correctly identified target words did not differ significantly between the patients with psychotic major depression (mean=12.70, SD=0.83), the patients with nonpsychotic major depression (mean=13.41, SD=0.49), and the healthy comparison subjects (mean=14.10, SD=0.57) (χ2=1.56, df=2, p=0.36). On average, healthy volunteers produced more correct responses (i.e., made fewer errors of omission) than did either patient group, and the two patients groups had a similar number of correct responses. However, the subjects with psychotic major depression showed a higher rate of errors of commission (incorrectly identified distracters as targets) than did the subjects with nonpsychotic major depression or the healthy volunteers (χ2=7.26, df=2, p<0.03). The subjects with nonpsychotic major depression and the healthy volunteers did not differ significantly in errors of commission. Moreover, the higher rate of commission errors for the psychotic major depression group did not appear to be simply a function of symptom severity. Hamilton depression scale scores were higher for the psychotic major depression group (mean=35.5, SD=9.1) than for the nonpsychotic major depression group (mean=23.9, SD=3.7) (U=20.0, z=–3.32, p<0.01), but Hamilton depression scale scores were not significantly correlated with errors of commission (r=0.32, df=25, p=0.07) and did not contribute additional explained variance above diagnosis (R2 change=0.001, F change=0.021, df=1, 24, p=0.89). In each of the three groups, the cortisol level did not correlate significantly with errors of commission or errors of omission.

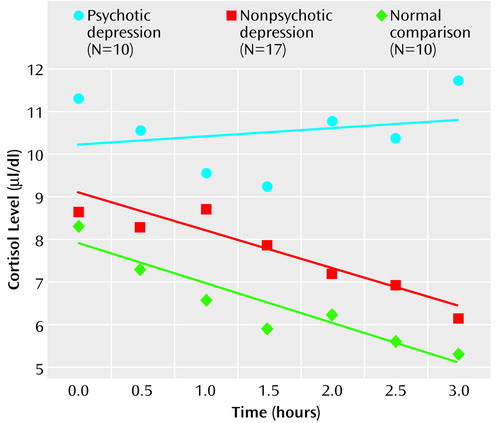

On the afternoon cortisol test, the subjects with psychotic major depression had significantly higher average cortisol levels than did the subjects with nonpsychotic major depression or the normal comparison subjects (for comparison subjects, mean rank=11.1; for patients with nonpsychotic major depression, mean rank=18.2; for patients with psychotic major depression, mean rank=27.3) (χ2=11.28, df=2, p=0.004). In a comparison of cortisol levels at each of the seven time points, statistically significant group differences were observed during three consecutive time points in the late afternoon (3:00 p.m.: χ2=6.5, df=2, p<0.04; 3:30 p.m.: χ2=7.9, df=2, p<0.02; 4:00 p.m.: χ2=10.7, df=2, p=0.005). Mean values on the afternoon cortisol test were higher for the subjects with psychotic major depression than for the subjects with nonpsychotic major depression and the comparison subjects. The mean values on the afternoon cortisol test were modestly higher for the subjects with nonpsychotic major depression than for the healthy comparison subjects. The 4:00 p.m. serum cortisol level most distinguished the psychotic major depression subjects from the nonpsychotic major depression subjects and the healthy volunteers (for comparison subjects, mean rank=12.9; for patients with nonpsychotic major depression, mean rank=15.7; for patients with psychotic major depression, mean rank=25.3) (χ2=12.18, df=2, p=0.02).

It is interesting to note that the average afternoon cortisol levels of the subjects with psychotic major depression did not decrease in a particularly linear fashion, compared to those of the normal comparison subjects and the subjects with nonpsychotic major depression. Specifically, the slope of the linear regression curve was virtually flat for the psychotic major depression subjects (b=–0.14, R2=0.03, p=0.71), indicating a relatively constant cortisol level throughout the afternoon. In contrast, the nonpsychotic major depression subjects (b=–0.90, R2=0.87, p<0.01) and the healthy volunteers (b=–0.96, R2=0.87, p<0.01) showed the expected pattern of decreasing cortisol levels over time (Figure 1). Statistical comparisons of change in cortisol levels over time were conducted by using the Fisher r-to-z transformation. Across the seven time points, the pattern of relatively constant cortisol levels observed for the subjects with psychotic major depression was statistically different from the reduction observed for both the normal comparison subjects (z=2.78, p<0.01) and the nonpsychotic major depression subjects (z=3.20, p<0.01).

Discussion

This study indicates a significant relationship between the diagnosis of psychotic major depression and the ability to perform accurately on the Wallach Memory Recognition Test. Patients with psychotic major depression were not impaired in their ability to recognize correctly previously presented words. However, their higher rate of commission errors in a test of recognition memory suggests that they had difficulty discriminating between previously presented relevant information (targets) and irrelevant new information (distracters).

Our findings for patients with psychotic major depression are consistent with those of Wolkowitz et al. (15), who found that both depressed patients who were nonsuppressors of cortisol on the dexamethasone suppression test and healthy volunteers who were given exogenous corticosteroids made significantly more errors of commission than omission on the Wallach Memory Recognition Test. Similar to the results for healthy comparison subjects given corticosteroids, our results suggest that patients with psychotic major depression, who have a “naturally” perturbed hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, have great difficulties in distinguishing between relevant and irrelevant stimuli.

The mechanisms by which corticosteroids may alter cognition are uncertain. However, our findings appear to be consistent with electrophysiological findings that acute administration of cortisol to human subjects reduces the average evoked potential response to relevant but not to irrelevant stimuli (22). Increased cortisol levels may lead to less accurate encoding of meaningful stimuli and may impair selective attention, thereby reducing an individual’s ability to discriminate relevant and important information from irrelevant and unimportant information. Glucocorticoids have been reported to affect working memory in humans (17). Our group has reported that in squirrel monkeys, cortisol fed without restriction in drinking water resulted in impairment on an object-retrieval task, a test of prefrontal cortical function (23). These data point to effects of glucocorticoids on attention and response inhibition.

From a pragmatic point of view, quantifiable early recognition of psychotic major depression is extremely important because psychotic major depression has greater morbidity and requires a different treatment regimen than nonpsychotic major depression. Furthermore, because psychosis in major depression occurs in individuals who are not otherwise psychotic and who are partly able to recognize when they are having disordered thinking, patients with psychotic major depression often deny their psychotic symptoms. In addition, psychosis in psychotic major depression appears to occur along a continuum from unjustified suspicion to frank hallucinations and delusions. We have previously proposed that cognitive performance, rather than specific symptoms, may provide greater specificity in separating patients with psychotic major depression from patients with nonpsychotic major depression (6). A noninvasive test like the Wallach Memory Recognition Test, which may help in the accurate diagnosis of psychotic major depression in patients with depression who deny overt psychosis, may be of great benefit in formulating an appropriate treatment plan.

Our finding that subjects with psychotic major depression were hypercortisolemic before treatment, as measured by the afternoon cortisol test, confirms multiple previous findings suggesting that patients with psychotic major depression represent a biologically discernible subset of subjects with major depression (1). It is also noteworthy that the normal rhythm and expected decline in cortisol values throughout the afternoon was absent for the psychotic major depression group. For the patients with nonpsychotic major depression, cortisol levels were only slightly higher than for the normal comparison group, and these patients had a normal afternoon rhythm. In fact, the lower the nonpsychotic major depression subjects’ cortisol values, the more errors of omission they made. It is possible that patients with psychotic major depression, who appear hyperaroused, have an inability to distinguish between target words and distracters because they internally generate stimuli that impair their ability to accurately attend and remember (more errors of commission). On the other hand, patients with nonpsychotic major depression may be underaroused, and their ability to simply attend is impaired (more errors of omission). Peak cognitive function may be achieved at a moderate level of cortisol-induced arousal, where the ability to attend and remember is neither impaired by overstimulation or impaired by understimulation.

Although it has been frequently noted that the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is altered in depression, the diagnosis of depression by means of laboratory measures has been elusive because of the lack of specificity. A high and/or relatively flat afternoon cortisol curve may be a correlate of psychotic major depression (or depression with significant cognitive impairment) and may biologically separate psychotic from nonpsychotic depression. Empirically, these two groups appear to require quite different pharmaceutical therapies to treat the two types of depression.

Conclusions

Alterations in the HPA axis of depressed patients may be clinically significant because they may significantly alter the ability to process new information, to filter out distractions, and to respond to environmental changes. Endocrinologic treatments of depression, particularly those that modulate cortisol, are worthy of further examination, since preliminary results show promise. We are currently testing mifepristone, a cortisol receptor antagonist, in an attempt to rapidly reverse psychosis and to improve the cognitive function of patients with psychotic major depression.

Received May 31, 2000; revisions received Dec. 11, 2000, and April 6, 2001; accepted April 25, 2001. From the Department of Psychiatry, Stanford University School of Medicine. Address reprint requests to Dr. Belanoff, Department of Psychiatry, Stanford University School of Medicine, 401 Quarry Rd., Stanford, CA 94305; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grants from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression and the Pritzker Foundation, NIMH grants MH-47573 and MH-19938, and grant RR-00070 from the NIH General Clinical Research Center Program. The authors thank Jacob Ballon, Jennifer Jurik, and Tunghi May Pini for their assistance.

Figure 1. Mean Cortisol Levels for Subjects With Psychotic and Nonpsychotic Major Depression and Normal Comparison Subjects, 1:00–4:00 p.m.

1. Schatzberg AF, Rothschild AJ: Psychotic (delusional) major depression: should it be included as a distinct syndrome in DSM-IV? Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:733-745Link, Google Scholar

2. Rothschild AJ, Benes F, Hebben N, Woods B, Luciana M, Bakanas E, Samson JA, Schatzberg AF: Relationships between brain CT scan findings and cortisol in psychotic and nonpsychotic depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry 1989; 26:565-575Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Nelson EB, Sax KW, Strakowski SM: Attentional performance in patients with psychotic and nonpsychotic major depression and schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:137-139Link, Google Scholar

4. Jeste DV, Heaton SC, Paulsen JS, Ercoli L, Harris J, Heaton RK: Clinical and neuropsychological comparison of psychotic depression with nonpsychotic depression and schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:490-496Link, Google Scholar

5. Basso MR, Bornstein RA: Neuropsychological deficits in psychotic versus nonpsychotic unipolar depression. Neuropsychology 1999; 13:69-75Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Schatzberg AF, Posener JA, DeBattista C, Kalehzan BM, Rothschild AJ, Shear PK: Neuropsychological deficits in psychotic versus nonpsychotic major depression and no mental illness. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1095-1100Link, Google Scholar

7. Kim DK, Kim BL, Sohn SE, Lim S-W, Na DG, Paik CH, Krishnan RR, Carroll BJ: Candidate neuroanatomic substrates of psychosis in old-aged depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 1999; 23:793-807Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Rubinow DR, Post RM, Savard R, Gold PW: Cortisol hypersecretion and cognitive impairment in depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:279-283Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Winokur G, Black DW, Nasrallah A: DST nonsuppressor status: relationship to specific aspects of the depressive syndrome. Biol Psychiatry 1987; 22:360-368Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Brown WA, Qualls CB: Pituitary-adrenal disinhibition in depression: marker of a subtype with characteristic clinical features and response to treatment? Psychiatry Res 1981; 4:115-128Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Demeter E, Rihmer Z, Arato M, Frecska E: Association performance and the DST (letter). Psychiatry Res 1986; 18:289-290Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Sikes CR, Stokes PE, Lasley BJ: Cognitive sequelae of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) dysregulation in depression (abstract). Biol Psychiatry 1989; 25:148A-149ACrossref, Google Scholar

13. Newcomer JW, Craft S, Hershey T, Askins K, Bardgett ME: Glucocorticoid-induced impairment in declarative memory performance in adult humans. J Neurosci 1994; 14:2047-2053Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Newcomer JW, Selke G, Melson AK, Hershey T, Craft S, Richards K, Alderson AL: Decreased memory performance in healthy humans induced by stress-level cortisol treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:527-533Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Wolkowitz OM, Reus VI, Weingartner H, Thompson K, Breier A, Doran A, Rubinow D, Pickar D: Cognitive effects of corticosteroids. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1297-1303Link, Google Scholar

16. Sheline YI, Sanghavi M, Mintun MA, Gado MH: Depression duration but not age predicts hippocampal volume loss in medically healthy women with recurrent major depression. J Neurosci 1999; 19:5034-5043Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Lupien SJ, Gillin C, Hauger RL: Working memory is more sensitive than declarative memory to the acute effects of corticosteroids: a dose-response study in humans. Behav Neurosci 1999; 113:420-430Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56-62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Wechsler D: WAIS-R Manual. New York, Psychological Corp, 1981Google Scholar

20. Wallach J, Riege W, Cohen M: Recognition memory for emotional words: comparative study of young, middle-aged, and older persons. J Gerontol 1980; 35:371-375Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Halbreich U, Zumoff B, Kream J, Fukushima DK: The mean 1300-1600 h plasma cortisol concentration as a diagnostic test for hypercortisolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1982; 54:1262-1264Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Kopell BS, Wittner WK, Lunde D, Warrik G, Edwards D: Cortisol effects on average evoked potentials, alpha-rhythm, time estimation, and two-flash fusion threshold. Psychosom Med 1970; 32:39-49Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Lyons DM, Lopez JM, Yang C, Schatzberg AF: Stress-level cortisol treatment impairs inhibitory control of behavior in monkeys. J Neurosci 2000; 20:7816-7821Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar