Attentional Performance in Patients With Psychotic and Nonpsychotic Major Depression and Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors examined Continuous Performance Test scores of patients with major depression with or without psychosis and schizophrenia. METHOD: Patients with major depression with psychosis (N=13), major depression without psychosis (N=14), and schizophrenia (N=15) and normal volunteers (N=14) completed the degraded-stimulus version of the Continuous Performance Test. Patients were rated with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and measures of positive formal thought disorder. RESULTS: Continuous Performance Test scores of patients with major depression with psychosis and schizophrenia were significantly worse than those of patients with major depression without psychosis and of normal volunteers. Positive formal thought disorder was correlated with performance on this test in patients with schizophrenia. CONCLUSIONS: These findings suggest that attentional impairment on the Continuous Performance Test is associated with psychosis in general and may be specifically associated with positive formal thought disorder in patients with schizophrenia. (Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:137–139)

The Continuous Performance Test has been used to demonstrate deficits in core attentional functioning in schizophrenia, mania, and major depression (1, 2), although no studies have evaluated performance on this test specifically in psychotic depression. Attentional deficit has been found to be associated with positive formal thought disorder in schizophrenia but not in mania (3). The purpose of the current study was to determine whether patients with psychotic depression exhibit a deficit on the Continuous Performance Test. We also examined whether Continuous Performance Test deficits were specifically associated with depressive symptoms, psychotic symptoms (i.e., thought disorder), or both by correlating measures of these symptoms with performance on the test and by comparing performance among patients with psychotic depression, nonpsychotic depression, and schizophrenia and normal volunteers.

METHOD

Patients 18–60 years old were recruited from inpatient and outpatient settings at the University of Cincinnati Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects after the study procedure had been fully explained. Diagnoses were made with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Version (SCID-P) (4), performed by psychiatrists experienced with this instrument (kappa of interrater reliability=0.94). Substance use disorders were also identified with the SCID-P. Patients who met DSM-III-R criteria for unipolar major depression without psychotic features (N=14), unipolar major depression with psychotic features (N=13), or schizophrenia (N=15) were included in the study. Patients were excluded if they had a neurological disorder or mental retardation. Patients with substance use diagnoses (N=8) had not used substances within 1 week of Continuous Performance Test administration and symptom ratings, with the exception of two patients who had used substances more than 3 days before testing but exhibited no symptoms of withdrawal at the time of the Continuous Performance Test. These two patients performed above the mean of their diagnostic groups on the Continuous Performance Test. Healthy volunteers (N=14) who had no history of psychiatric illness or substance use disorders, as determined by the SCID-P, were recruited by advertising and word of mouth. These volunteers reported no symptoms of depression, anhedonia, or psychosis.

Symptoms were rated within 2 days of Continuous Performance Test administration through use of the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (5) and the positive formal thought disorder subscale (items 26–32) from the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (6).

The computerized version of the degraded-stimulus Continuous Performance Test (provided by K. Nuechterlein, UCLA, Los Angeles, 1983) was administered to all subjects. This version of the test randomly presents on a computer screen perceptually degraded (i.e., blurred) numbers between 0 and 9 for 35 msec each, at a rate of 1 per second. Subjects respond to the target stimulus (the number 0) by pressing a button. A total of 480 trials, 25% of them targets, were divided into six successive blocks presented over 8 minutes. Probabilities of hits and false alarms were used to calculate signal-detection indices (7). The nonparametric performance measure of sensitivity was calculated (8). The term sensitivity refers to the signal/noise discrimination level.

All statistical analyses were performed by using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C., 1991). Analyses of variance and covariance (ANCOVA) with post hoc Tukey tests were used to compare the four groups on continuous variables. Continuous Performance Test sensitivity values were ranked before the ANCOVA because of the small group size. Categorical variables were analyzed with chi-square tests. Pearson product-moment correlations were calculated to assess relationships between symptom ratings and Continuous Performance Test sensitivity measures, as well as between Continuous Performance Test performance and antipsychotic dose. Other analyses were performed as necessary for completeness.

RESULTS

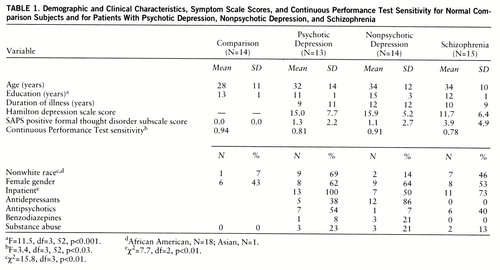

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects are presented in table 1. Significant differences were found among groups in racial distribution, education, and inpatient status. Analyses revealed that the nonpsychotic depression and comparison groups had significantly more education than the psychotic depression and schizophrenia groups. There was a significant difference among groups on Continuous Performance Test sensitivity with covariance for education and race. Post hoc analyses (Tukey's honest significant difference, p<0.05) revealed that the schizophrenia and psychotic depression groups performed significantly worse than both the nonpsychotic depression group and comparison subjects on this test.

Race, substance abuse, and antidepressant treatment were not associated with Continuous Performance Test sensitivity in this group. In addition, there was no correlation between the dose of antipsychotic medication in chlorpromazine equivalents and performance on this test. Among the patient groups, inpatients performed significantly worse than outpatients on the Continuous Performance Test (t=3.02, df=39, p<0.005). ANCOVA of the patient groups, with adjustment for inpatient status, in addition to education and race, did not change the differences in performance on this test among the patient groups. There was no significant difference in mean Hamilton scale scores or positive formal thought disorder ratings among the diagnostic groups. Hamilton scale scores did not correlate with Continuous Performance Test sensitivity in any of the groups. Positive formal thought disorder and Continuous Performance Test sensitivity were significantly correlated in the schizophrenia group only (Pearson product-moment, r=–0.66, df=13, p<0.01). The correlations of positive formal thought disorder and Continuous Performance Test sensitivity were compared among the groups, revealing a significant difference only between the schizophrenia and nonpsychotic depression groups (t∝=1.8, df=1, p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we observed a Continuous Performance Test deficit in patients with major depression with psychosis that was similar to that of patients with schizophrenia. Test performance of the psychotic depression group was significantly worse than that of the nonpsychotic depression group, who did not differ significantly from comparison subjects on this measure of attention. These findings suggest that deficits in Continuous Performance Test performance in major depression occur only in the presence of psychosis; this is consistent with findings from previous studies (9, 10). The finding that depressed patients do as well as comparison subjects on the Continuous Performance Test when numbers are used as the stimuli is consistent with previous findings (2). Moreover, depression scores were not correlated with impaired performance on this test.

Our finding that positive thought disorder and Continuous Performance Test performance are correlated in schizophrenia is consistent with previous work by Pandurangi et al. (3). The reason for the lack of this correlation in psychotic depression is unclear. However, Schatzberg et al. (11) have hypothesized a mechanism for cognitive impairment in psychotic depression that differs from that of schizophrenia. Specifically, they propose that psychosis in depression may be caused by increased cortisol levels, which may be more pronounced in psychotic depression than in nonpsychotic depression, leading to the greater neuropsychological deficits, including decreased attention, seen in psychotic depression. However, the correlations of positive formal thought disorder with Continuous Performance Test performance between the psychotic depression and schizophrenia groups did not significantly differ, so these results should be interpreted cautiously.

Our study evaluated subjects' attentional functioning only during the acute psychotic episode, so it does not provide data to clarify whether the attentional deficit in psychotic depression is a state-dependent characteristic (which resolves with remission of the acute episode), a trait-dependent characteristic (and, thus, a possible marker for this subtype of depression), or a mediating vulnerability indicator (which improves but does not fully resolve with remission of the acute episode) (1). A study comparing Continuous Performance Test scores of patients with psychotic depression during the acute episode and then after remission would clarify this issue.

Several limitations of this study should be considered when interpreting these results. The most significant limitation is the relatively small group size. Moreover, the patient groups differed in terms of educational level, race, and inpatient status. In addition, all of the subjects were recruited from treatment populations. Because of the demographics of the locale in which this study was conducted, only two major ethnic groups were adequately represented in the patient group. This limits the degree to which these findings can be generalized to the population as a whole. Nonetheless, to our knowledge, this is the first report comparing Continuous Performance Test scores among groups of patients with psychotic depression, nonpsychotic depression, and schizophrenia.

|

Received Feb. 12, 1997; revision received July 11, 1997; accepted July 18, 1997. From the Psychotic Disorders Research and Biological Psychiatry Programs, Department of Psychiatry, University of Cincinn ati College of Medicine. Address reprint requests to Dr. Nelson, Bio logical Psychiatry Program, P.O. Box 670559, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, 231 Bethesda Ave., Cincinnati, OH 45267-0559. S upported in part by grants from the Scottish Rite Benevolent Foun dation's Schizophrenia Research Program, N.M.J., and the Ohio Department of Mental Health and by NIMH grant MH-54317 (Dr. Strakowski).

1. Nuechterlein K, Dawson M, Ventura J, Miklowitz D, Konishi G: Information-processing anomalies in the early course of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res 1991; 5:195–196Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Cornblatt BA, Lenzenweger MF, Erlenmeyer-Kimling L: The Continuous Performance Test, Identical Pairs Version, II: contrasting attentional profiles in schizophrenic and depressed patients. Psychiatry Res 1989; 29:65–85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Pandurangi A, Sax K, Pelonero A, Goldberg S: Sustained attention and positive formal thought disorder in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1994; 13:109–116Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Version 1.0 (SCID-P). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

5. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1982Google Scholar

7. Davies D, Parasuraman R: The Psychology of Vigilance. London, Academic Press, 1982Google Scholar

8. Grier J: Nonparametric indexes for sensitivity and bias. Psychol Bull 1971; 75:424–429Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Jeste DV, Heaton S, Paulsen JS, Ercoli L, Harris MJ, Heaton RK: Clinical and neuropsychological comparison of psychotic depression with nonpsychotic depression and schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:490–496Link, Google Scholar

10. Rothschild A, Benes F, Hebben N, Woods B, Luciana M, Bakanas E, Samson JA, Schatzberg AF: Relationship between brain CT scan findings and cortisol in psychotic and non-psychotic depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry 1989; 26:565–575Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Schatzberg AF, Rothschild AJ, Langlais PJ, Bird ED, Cole JO: A corticosteroid/dopamine hypothesis for psychotic depression and related states. J Psychiatr Res 1985; 19:57–64Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar