Comparison of Sertraline and Nortriptyline in the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder in Late Life

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study was designed to evaluate the comparative efficacy and safety of sertraline and nortriptyline for the treatment of major depressive disorder in older adults. METHOD: A double-blind, parallel group design was used to compare 210 outpatients, 60 years of age and older, who met DSM-III-R criteria for major depressive episode and had a minimum Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score of 18. The patients were randomly assigned to 12 weeks of treatment with either sertraline (50–150 mg/day) or nortriptyline (25–100 mg/day). RESULTS: The safety profiles of the two treatments were similar except that nortriptyline treatment was associated with a significant increase in pulse rate, whereas sertraline was associated with a nonsignificant decrease. Efficacy of both drugs was similar for both treatments at all time points, with 71.6% (N=53 of 74) of the sertraline-treated patients and 61.4% (N=43 of 70) of the nortriptyline-treated patients achieving responder status by week 12. Time to response was also similar, with more than 75% of the improvement in scores on the Hamilton depression scale having occurred by week 6. Secondary efficacy measures (posttreatment measures of cognitive function, memory, and quality of life) revealed a significant advantage for sertraline treatment. CONCLUSIONS: Primary efficacy measures showed sertraline and nortriptyline to be similarly effective. With secondary outcome measures there was consistent evidence of an advantage for the sertraline-treated group. The clinical impact of these measures on the long-term well-being of elderly depressed patients should be examined in a study of maintenance treatment.

Major depressive disorder in late life is a multidimensional illness that affects not only mood and the feeling of well-being, but also the physical, social, and cognitive functioning of older adults (1, 2). It is associated with higher rates of mortality, suicide, and cognitive impairment (3, 4). Although several antidepressants have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of late-life depression, far less research has been directed to examining the benefits of treatment across a spectrum of secondary measures, such as improvements in quality of life, functional status, memory, and cognition. The current study was undertaken to provide such a multidimensional assessment of the efficacy and safety of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) sertraline compared to the secondary amine tricyclic antidepressant nortriptyline.

Nortriptyline was chosen as the comparator because it has demonstrated efficacy in the elderly that equals or exceeds that of SSRI antidepressants (5–7). In addition, nortriptyline appears to be safe and well tolerated in the elderly (8).

The current study was designed as a double-blind comparison of 12 weeks duration, both to permit more gradual titration of nortriptyline and because previous studies of shorter duration had reported relatively low response rates (9). In addition to symptom severity measures, outcome was assessed by using measures of quality of life, memory, and cognitive functioning.

Method

Subjects

The subjects were male and female community-dwelling elderly outpatients aged 60 and over who met DSM-III-R criteria for single-episode or recurrent major depression and whose 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (10) scores were ≥18. Exclusion criteria for the study were a DSM-III-R diagnosis of acute or chronic organic mental disorder, a Mini-Mental State examination (11) score < 23, concomitant use of any psychotropic drug (except intermittent use of chloral hydrate or temazepam specifically for sleep), presence of another axis I psychiatric disorder, or any acute or unstable medical condition that might interfere with safety or the interpretation of results. Patients were recruited from two sources: depressed individuals seeking treatment at the geriatric psychiatry specialty clinics at each study center as well as patients identified through notices in the media.

The study was approved by the institutional review board at each of the 12 collaborating centers. The benefits and risks of study participation were fully explained to each patient, and written informed consent was obtained.

Study Design

Following a 1-week, single-blind placebo washout period, patients were randomly assigned to 12 weeks of double-blind, parallel treatment with either sertraline (in a flexible daily dose of 50–150 mg) or nortriptyline (in a flexible daily dose of 25–100 mg) provided on a three times per day schedule. A double-dummy procedure was used to preserve the blind.

Nortriptyline was initiated at a dose of 25 mg in the evening and could be titrated in increments of 25 mg per week to a maximal daily dose of 100 mg. The maximal dose could be initiated as early as the end of week 3. Sertraline treatment was initiated at a dose of 50 mg in the evening and could be titrated in increments of 50 mg every 3 weeks to a maximal daily dose of 150 mg. The maximal dose could be initiated as early as week 6. Doses of nortriptyline above 25 mg were divided as recommended in the manufacturer’s prescribing information, while all sertraline doses were administered in the evening. Daily doses of both drugs were increased on the basis of tolerability and lack of clinical response and could be decreased because of adverse effects at any time during the course of the study. Compliance with study treatment was monitored by pill counts, and patients who were less than 75% compliant for two subsequent visits were dropped from the study.

Assessments

Patients were evaluated at study entry with a psychiatric history and semistructured interview that included a DSM-III-R diagnostic checklist. A medical history, physical examination, and laboratory testing were performed. Patients underwent a full battery of investigator-rated assessments: the 24-item Hamilton depression scale (10); the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (12); and the 7-point Clinical Global Impression (CGI) severity and improvement scales (13). Instructions about rating were provided, and an interrater reliability session was held at an investigator meeting. Structured versions of the Hamilton scales were not used, nor was interrater reliability checked during the course of the study. Patient-rated assessments included the Profile of Mood States (POMS) (14) and the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (15), a validated 92-item instrument.

Cognitive function was assessed by means of the digit symbol substitution subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (16); the “shopping list task,” which is a standardized protocol that uses a selective reminding procedure designed to quantify short- and long-term memory storage and retrieval (17, 18); and the Mini-Mental State examination (11).

Safety assessments included weekly measurements of pulse and blood pressure (sitting and standing) and a review of adverse effects and concomitant medications. Laboratory assessments and ECGs were performed at baseline and at weeks 4 and 12. Finally, adverse events were assessed by means of an open-ended inquiry.

Plasma Drug Concentrations

Blood samples (10 ml) were collected in heparinized Vacutainer tubes for monitoring of plasma drug concentration on day 1 of the placebo washout period and after 1, 3, 6, and 12 weeks of double-blind treatment. Patients were instructed not to take study medication on visit days until after plasma samples had been obtained. Plasma samples were immediately placed on ice before being centrifuged at 5C for 15 minutes; they were then placed in specimen tubes that were stored at –20C until shipped on dry ice for analysis. Sertraline and N-desmethylsertraline assays were performed by gas chromatography that used an electron capture detection method (19). The intraassay coefficient of variation for the assay was less than 5%. Nortriptyline was similarly assayed (20), with an intraassay coefficient of variation also less than 5%.

Data Analysis

All efficacy measures were analyzed on the basis of an intention-to-treat, last-observation-carried-forward approach. For continuous measures at baseline, the two treatment groups were examined for comparability with two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) models that included treatment group and center main effects as well as the treatment-by-center interaction effect. For demographic characteristics, Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel general association statistics were used, stratifying by center, to test for comparability at baseline, where appropriate.

For all continuous efficacy measures, with the exception of the CGI improvement score, the mean score and the mean change from baseline score were computed; for the CGI improvement score, only mean scores were computed. The significance of mean changes from baseline were determined with respect to within-group and between-group differences by using least square means from two-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models with baseline values as covariates. Where only mean scores were computed, their significance was determined with respect to within-group and between-group differences by using least square means from two-way ANOVA models. Treatment group, center, and treatment-by-center interaction terms were included in all models except for the comparison of change from baseline in Hamilton depression scale total score between patients within and outside of the nortriptyline therapeutic range, for which only range status (within or outside) is included as a main effect in the ANCOVA model. All analyses were performed for patients available at each study visit and at the last observation carried forward for each patient.

A “mixed-model” ANOVA was employed for the analyses of change at multiple time points. According to Akaike’s information criterion (21), a model that employed an unstructured covariance matrix was shown to be optimal over a model that employed a compound symmetry or autoregressive order one structure. The least squares adjusted mean difference between sertraline and nortriptyline treatment on each primary outcome measure was reported with this model along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to express the precision of the estimates.

Treatment comparisons of responder and remitter rates for the full patient cohort were performed by using a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel general association statistic after controlling for treatment center. For subgroup comparisons of responder and remitter rates, a logistic model that contained treatment group and center effects and used the standard logit transformation or Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed) was used where appropriate. All significance levels were two-tailed and set at the 0.05 level.

To compare sertraline- and nortriptyline-treated patients with respect to the time to achieve “responder” status and the time to achieve “remitter” status, a survival analysis that used Kaplan-Meier estimates of the survival function was used (22). This model allows for censored data and does not assume any specific distribution of survival times.

Primary outcome measures consisted of the change from baseline in Hamilton depression scale total score; responder status, defined a priori as a 50% or greater reduction from baseline in Hamilton scale score; and CGI severity and improvement scores. Patients were defined as having remitted if their endpoint Hamilton depression scale score was £7.

Secondary outcome measures included changes from baseline on assessments of cognitive functioning and quality of life. In assessing, for example, the effects of treatment on cognitive functioning, the POMS confusion factor and Mini-Mental State scores were examined in addition to performance on the digit symbol substitution and the shopping list tasks. To assess treatment-related changes in energy and motivation, the Hamilton depression scale energy/motivation factor and POMS vigor and fatigue factors were examined. To assess treatment-related changes in the associated symptoms of anxiety, the Hamilton anxiety scale total score, Hamilton depression scale anxiety/somatization factors, and the POMS anger/hostility and tension/anxiety factors were examined. Treatment effects on the associated symptoms of insomnia were examined with the Hamilton depression scale sleep factor. To assess functional status and satisfaction, the physical, psychological, and social functioning scales from the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire were analyzed, as were the leisure time satisfaction factor and the global satisfaction item.

Results

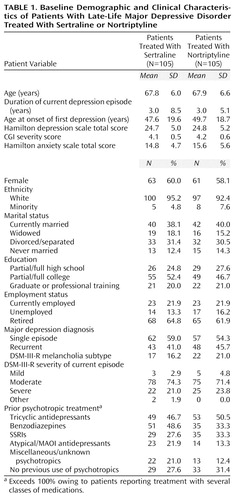

There were no significant between-group differences on any baseline demographic or depression-related clinical variables, which are summarized in Table 1. Of note is the mean duration of illness reported by study patients (3.0 years, SD=7.0), which suggests a relatively high degree of chronicity. Also of note is the previous exposure to antidepressant and anxiolytic treatment by the study group: 70.0% (N=147) reported previous use of psychotropic medications.

Out of 276 patients who entered the placebo washout phase of the study, 210 were randomly assigned to treatment, and 208 (the intent-to-treat group in the efficacy analyses) were available for at least one postrandomization assessment. Seventy-four patients treated with sertraline (70.5%) and 70 patients treated with nortriptyline (66.7%) completed the full 12 weeks of study treatment. The mean sertraline doses at 6 and 12 weeks were 77 mg/day (SD=29) and 96 mg/day (SD=41), respectively. The mean nortriptyline doses at 6 and 12 weeks were 75 mg/day (SD=25) and 78 mg/day (SD=26), respectively.

Twenty patients treated with sertraline (19.0%) and 19 patients treated with nortriptyline (18.1%) discontinued the study and cited adverse events as the primary reason (whether or not the adverse events were deemed by the investigator to be related to the study drug). One patient from each treatment group cited lack of efficacy as the reason for discontinuation.

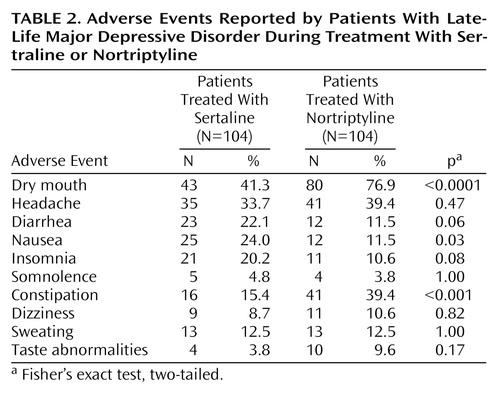

The rates of treatment-related adverse events reported by patients receiving sertraline and nortriptyline are presented in Table 2. Neither treatment resulted in clinically significant or sustained adverse effects on blood pressure, blood chemistry, or hematological indices. Of potential interest is the differential effect of treatment on supine and standing heart rate. On average, sertraline treatment resulted in a modest reduction in both supine and standing heart rate. In contrast, nortriptyline treatment, from week 2 on, was associated with an approximately 8%–10% increase in both supine and standing heart rate. At week 12, the adjusted changes from pretreatment baseline in supine heart rate for the sertraline- and nortriptyline-treated patients were –2.3 and 6.7, respectively (F=35.3, df=1, 120, p<0.0001); the adjusted changes in standing heart rate were –1.2 and 5.8 (F=12.2, df=1, 120, p<0.001). There were no age effects evident in the heart rate results.

Clinical Response

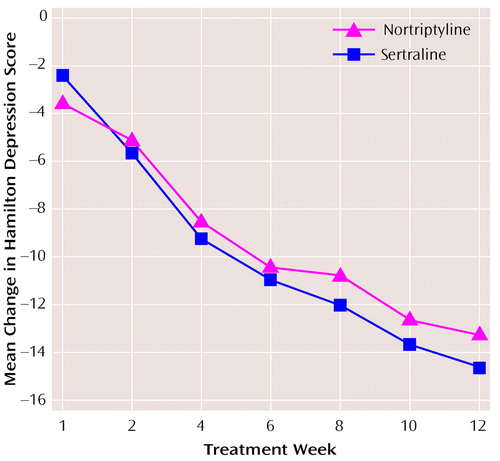

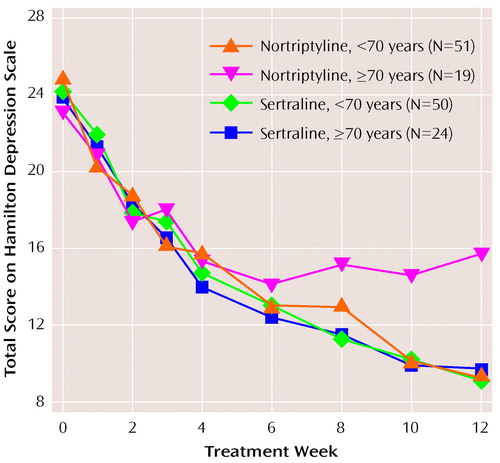

Figure 1 shows the mean adjusted changes in the Hamilton depression scale total scores over the 12 weeks of the study. Using a reported-measures mixed model, the improvement slope was comparable for sertraline and nortriptyline treatment. The repeated-measures mixed model result for the interaction of time and treatment group was nonsignificant (F=0.67, df=1, 188, p=0.41). There was no center-by-treatment interaction. The time course of antidepressant response appeared to be comparable for sertraline and nortriptyline. The 95% CI for the mean difference between the treatments in Hamilton depression scale total score over the course of 12 weeks of study treatment was –0.9 to 2.2, with sertraline slightly favored. Additional repeated-measures mixed models were also nonsignificant for the interaction of time and treatment group for the CGI measures of severity (F=0.77, df=1, 188, p=0.38) and improvement (F=0.19, df=1, 188, p=0.67). Again, there was no interaction noted between center and treatment.

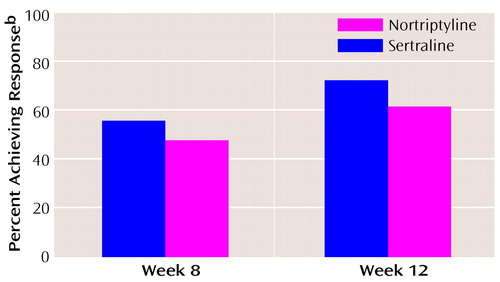

Response rates (≥50% reduction from baseline in 24-item Hamilton depression scale total score) were similar for both sertraline and nortriptyline treatments at all time points. By week 8, 55.8% (N=43 of 77; 95% CI=44.0%–67.0%) of sertraline-treated patients and 47.6% (N=39 of 82; 95% CI=36.0%–59.0%) of nortriptyline-treated patients had responded. At week 12, 72.4% (N=55 of 76; 95% CI=61.0%–82.0%) of sertraline-treated patients and 61.4% (N=43 of 70; 95% CI=49%–73%) of nortriptyline-treated patients had responded (Figure 2). The more conservative endpoint (last observation carried forward) analysis revealed an expected lower response rate, but in neither case was there a significant difference in the percentage of responders in the sertraline or nortriptyline treatment groups. Similar efficacy was demonstrated for sertraline and nortriptyline treatments in the mean change in the CGI severity score and the week 12 mean CGI improvement score.

To test whether nortriptyline or sertraline might differ in antidepressant efficacy among patients with high depression severity at baseline (defined as a Hamilton depression scale total score >26), we performed a two-way ANOVA that compared the week 12 changes from baseline in Hamilton depression scale total score and CGI severity score as well as the week 12 CGI improvement score. There was no interaction between treatment group and baseline severity on any of the three primary outcome measures, either by a completer or a last-observation-carried-forward analysis. The largest F value was obtained for the last-observation-carried-forward analysis of the change in Hamilton depression scale score (F=0.99, df=1, 201, p=0.32). This analysis yielded a 2.3-point difference (95% CI=–1.2 to 5.7) in Hamilton depression scale outcome in favor of sertraline.

The effect of the two study treatments on patient-rated measures of depression was also compared. An ANCOVA model that used baseline as a covariate and that included treatment, center, and the center-by-treatment interaction found significantly greater improvement on the POMS total score and several of the POMS factor scores that began at week 2 for the patients treated with sertraline. At endpoint, significant differences that favored sertraline treatment were observed in the POMS total score (F=4.25, df=1, 179, p<0.05), as well as the POMS factors of anger/hostility (F=5.60, df=1, 179, p<0.02), vigor (F=4.90, df=1, 179, p<0.03), fatigue (F=7.23, df=1, 179, p<0.008), and confusion (F=8.01, df=1, 179, p<0.006). Improvements in the tension/anxiety and depression/dejection factors were comparable for the two treatment groups.

Age and Treatment Response

An ANOVA performed on study completer data (Figure 3) revealed a significant treatment-by-age interaction for the Hamilton depression scale total score (F=11.2, df=1, 141, p=0.001). An ANOVA performed on the last-observation-carried-forward data also found a significant treatment-by-age interaction (F=7.5, df=1, 200, p=0.007). This was confirmed in a mixed-model ANOVA as well. Graphical and post hoc analyses decomposing the interaction indicated that patients 70 years old and over who were taking nortriptyline did significantly less well than those under 70. For the patients treated with sertraline, age did not appear to influence outcome.

In order to eliminate differential attrition as a possible explanation for the superiority of sertraline among those 70 and over, a survival analysis was performed and Kaplan-Meier estimates of the survival function were computed and tested. Again, a significant advantage was found for sertraline over nortriptyline among patients 70 years old and over with respect to time to achieve responder status (log rank χ2=14.9, df=3, p<0.002). Similar results were obtained for the time to achieve remitter status (log rank χ2=9.6, df=3, p<0.02). Nonparametric analyses were also performed to address the potential problem of the lack of a normal distribution with similarly significant results.

The efficacy advantage of sertraline in patients 70 years old and over was confirmed for the other primary outcome measures: CGI severity (F=3.8, df=1, 141, p=0.053) and CGI improvement (F=7.4, df=1, 141, p=0.0007).

An examination of week-by-week change in Hamilton depression scale scores found that patients 70 years old and over who were treated with nortriptyline showed no additional improvement after week 6. In contrast, nortriptyline patients who were under 70, and patients taking sertraline who were both over and under age 70, continued to show reductions in Hamilton depression scale total scores throughout the 12-week course of study treatment.

Survival analyses that used Kaplan-Meier estimation found no difference between sertraline and nortriptyline in time to response (χ2=1.45, df=1, p=0.23) or time to remission (χ2=0.25, df=1, p=0.62).

Analysis of Treatment Response for Agitated and Retarded Subtypes

Sertraline treatment was associated with a 12-week response rate of 74.4% (N=32 of 43) in patients rated at baseline as being agitated (score on Hamilton depression scale item nine ≥>2). The 12-week response rate with nortriptyline treatment was 63.8% (N=30 of 47), but the difference between the two treatment groups was not significant (χ2=3.10, df=1, p=0.08). Retardation (score on Hamilton depression scale item eight ≥>2) at baseline was also associated with a differential, but not significant, 12-week response in the two treatments (χ2=1.76, df=1, p=0.18).

Cognitive, Behavioral, and Quality-of-Life Measures

The results of treatment across multiple measures that assessed domains of functioning affected by depression in the elderly are summarized in Table 3. There was consistent evidence, across almost all measures, suggesting a beneficial effect of sertraline treatment on cognitive functioning, whereas nortriptyline treatment was associated with a mildly negative effect on cognition. Similarly, sertraline-treated patients showed greater improvement in energy and in most quality-of-life measures. In contrast, both drugs had similarly beneficial effects on anxiety and sleep.

Use of Concomitant Medication

Concomitant medications were used by 70.0% (N=147) of patients during the course of the study. The most commonly used concomitant medications were acetaminophen (25%), aspirin (29%), ibuprofen (14%), conjugated estrogens (16% of female patients), calcium supplements (14%), multivitamin preparations (13%), and psyllium (8%). The protocol permitted use of chloral hydrate or temazepam on a limited, as-needed basis, and there were no significant between-group differences in the use of these hypnotics (16.2% [N=17] of the sertraline-treated and 13.3% [N=14] of nortriptyline-treated patients required hypnotics during the course of the study).

Plasma Levels and Outcome

The mean daily dose of nortriptyline from study week 4 on was 70 mg or above. After 12 weeks of treatment with nortriptyline, 18 patients had plasma levels below 50 ng/ml, 39 patients had plasma levels within the therapeutic range (50–150 ng/ml), and eight patients had plasma levels greater than 150 ng/ml. The rate of response did not differ in patients with nortriptyline plasma levels below 50 ng/ml or those with plasma levels 50–150 ng/ml, but patients with plasma levels above 150 ng/ml showed suggestive but nonsignificant lower rates of improvement (χ2=3.53, df=1, p=0.06). There was no correlation observed between plasma levels of sertraline (or N-desmethylsertraline) and treatment response or between plasma levels and side effect burden.

Discussion

The results of this double-blind study demonstrate that the efficacy and time course of improvement in the symptoms of major depressive disorder in older adult outpatients was comparable for both sertraline and nortriptyline treatment. Hamilton depression scale responder status at week 12 did not significantly differ between patients treated with sertraline and those treated with nortriptyline. Response rates for both drugs, however, were notably higher in the current study than in previous studies (5, 23–31), most of which employed a shorter treatment period of 6–8 weeks. This suggests that longer treatment periods may be important if antidepressant drugs are to be reliably evaluated in older adults (31). While about 75% of the observed Hamilton depression scale change score occurred by the end of 6 weeks (as seen in Figure 1), the remaining 25% of change was of clinical significance. The percentage of patients achieving clinical remission (Hamilton depression scale score ≤7) increased from 29% at week 6 to 54% at week 12 with sertraline treatment and from 31% to 50% with nortriptyline treatment.

The one exception to the equivalent antidepressant benefit of sertraline and nortriptyline was the efficacy advantage of sertraline, observed across all three primary outcome measures, in treating patients aged 70 years and older. Treatment with nortriptyline in the 70-and-over age group elicited improvement in Hamilton depression scale and CGI scores in the first 6 weeks but no further improvement thereafter. The reasons for this finding are unclear.

A distinguishing feature of the current study was the range of secondary outcome measures employed to assess cognitive, behavioral, and quality-of-life outcomes. There were notable differences on these outcomes that consistently favored sertraline treatment. These secondary outcome measures may reflect the selective vulnerability of older adults to the central anticholinergic activity of nortriptyline. In some instances (e.g., short-term memory and retrieval as measured by the recall and retrieval items on the shopping list task), 12 weeks of treatment with nortriptyline actually led to modest deterioration. These results are consistent with a previous study (32) that also demonstrated decrements in short-term verbal memory in elderly patients treated with nortriptyline. This more favorable side effect profile of sertraline appears to be clinically relevant given the well-documented neuropsychological deficits associated with depression in late life (33–35). The result is also not surprising since previous research (36) has suggested that nortriptyline has at least fivefold higher anticholinergicity than SSRI antidepressants.

Significantly greater clinical improvement in energy and vigor was also associated with sertraline treatment, while improvement in anxiety and impaired sleep was similar with both drugs despite the greater sedative effect of nortriptyline. Concomitant sleep medications (permitted in the protocol) were used at a similar rate by patients taking both study drugs, providing an indirect confirmation of similar levels of sleep improvement.

After 12 weeks of treatment with either sertraline or nortriptyline, perceived ability to function and quality of life, known to deteriorate in depressed older adults (37), improved significantly from pretreatment baseline. Sertraline treatment, however, was associated with a significantly greater improvement in all quality of life measures (except global satisfaction). Patients who received sertraline reported feeling better physically and psychologically and reported being more socially engaged than did nortriptyline-treated patients. This is a notable finding given the relative chronicity of the patients in the current study (mean illness duration of 3 years).

A methodological weakness of the current study is the lack of a placebo control. However, the magnitude and time course of the treatment effects on primary outcome measures were comparable to what has been reported for available placebo-controlled studies in the elderly, which suggests that real pharmacological effects were being observed. A second possible weakness may have been introduced by not adjusting nortriptyline doses according to plasma level determinations, which would have required burdensome design complexity to maintain the blind. This did not appear to affect outcome, since patients with apparently subtherapeutic plasma levels (less than 50 ng/ml) achieved response rates higher than patients with plasma levels that were within or above the therapeutic range. Alternatively, use of a fixed-dose design might have yielded results more applicable to efficacy and safety issues but less relevant to clinical practice. Finally, the relatively slow titration schedule of sertraline (50 mg every 3 weeks) may have served to delay its antidepressant response. The slow titration schedule was employed to maximize tolerability.

In conclusion, the results of the current study suggest that sertraline and nortriptyline are equally effective in the treatment of outpatient late-life major depression, including those patients presenting with severe depression. The one exception was the significant antidepressant advantage noted for sertraline across all three primary outcome measures in patients who were 70 years old and over. In addition, for the total patient group, significant clinical benefit in favor of sertraline was noted on most secondary outcome measures, including patient self-ratings such as the POMS, assessments of cognitive performance (e.g., the digit symbol substitution and shopping list tasks), quality of life, and perceived ability to function. The lack of cardio-acceleratory effects also distinguished sertraline treatment from treatment with nortriptyline. The results of this study need to be confirmed by additional prospective, double-blind trials that include a maintenance phase designed to assess the multidimensional impact of antidepressant treatment on the long-term well-being of the elderly depressed patient.

Acknowledgments

This study was completed with the participation of the following investigators: William Bondareff, M.D., Ph.D., USC School of Medicine, Los Angeles; Eugene A. DuBoff, M.D., Center for Behavioral Medicine, Wheat Ridge, Colo.; Sanford I. Finkel, M.D., Northwestern University Medical School, Chicago; Murray Alpert, Ph.D., and Arnold J. Friedhoff, M.D., New York University School of Medicine, New York; Jon F. Heiser, M.D., Pharmacology Research Institute, Long Beach, Calif.; Lawrence Jenkyn, M.D., and David J. Coffey, M.D., Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H.; William J. McEntee, M.D., Future HealthCare Research Center, Sarasota, Fla.; B. Ashok Raj, M.D., University of South Florida, Tampa; Stephen A. Rappaport, M.D., Methodist Hospital, Indianapolis; Steve Roose, M.D., New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York; Murray H. Rosenthal, D.O., Behavioral and Medical Research, San Diego; Myron Weiner, M.D., University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

|

|

|

Presented in part at the seventh congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, Jerusalem, Oct. 16–21, 1994; the 148th annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Miami, May 20–25, 1995; and the 20th congress of the Collegium Internationale Neuro-Psychopharmacologicum, Melbourne, June 23–27, 1996. Received Nov. 16, 1998; revision received Sept. 9, 1999; accepted Nov. 24, 1999. From the Department of Psychiatry, Division of Geriatric Psychiatry, USC School of Medicine; New York University School of Medicine, New York; and Pfizer Inc, New York. Address reprint requests to Dr. Bondareff, Department of Psychiatry, Division of Geriatric Psychiatry, USC School of Medicine, 1237 North Mission Rd., MOL 202, Los Angeles, CA 90033; [email protected] (e-mail). This research was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Figure 1. Mean Changes From Baseline in Total Score on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale for Patients With Late-Life Depression Treated With Sertraline (N=105) or Nortriptyline (N=105)a

aTotal N varies because of missing subject data at different time points.

Figure 2. Patients With Late-Life Depression Who Achieved Response After 8 and 12 Weeks of Treatment With Sertraline (N=105) or Nortriptyline (N=105)a

aBy week 12, 74 patients remained in the sertraline group and 70 remained in the nortripyline group.

bA ≥>50% reduction from baseline in total score on the Hamilton depression scale.

Figure 3. Relation of Age to Total Score on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale for Patients With Late-Life Depression Treated With Sertraline or Nortriptyline for 12 Weeks

1. Blazer DG, Koenig HG: Mood disorders, in Textbook of Geriatric Psychiatry, 2nd ed. Edited by Busse EW, Blazer DG. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995, pp 235–263Google Scholar

2. Schneider LS, Reynolds CF III, Lebowitz BD, Friedhoff AJ: Diagnosis and Treatment of Depression in Late Life. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994Google Scholar

3. Henriksson MM, Marttunen MJ, Isometsa ET, Heikkinen ME, Aro HM, Kuoppasalmi KI, Longqvist JK: Mental disorders in elderly suicide. Int Psychogeriatr 1995; 7:275–286Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Oxman TE: Antidepressants and cognitive impairment in the elderly. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(suppl 5):38–44Google Scholar

5. Nair NP, Amin M, Holm P, Katona C, Klitgaard N, Ng Ying Kin NM, Kragh-Sorensen P, Kuhn H, Leek CA, Stage KB: Moclobemide and nortriptyline in elderly depressed patients: a randomized, multicentre trial against placebo. J Affect Disord 1995; 33:1–9Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Georgotas A, McCue RE, Friedman E, Cooper TB: Response of depressive symptoms to nortriptyline, phenelzine and placebo. Br J Psychiatry 1987; 151:102–106Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Roose SP, Glassman AH, Attia E, Woodring S: Comparative efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclics in the treatment of melancholia. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1735–1739Google Scholar

8. Miller MD, Pollock BG, Rifai AH, Paradis CF, Perel JM, George C, Stack JA, Reynolds CF III: Longitudinal analysis of nortriptyline side effects in elderly depressed patients. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1991; 4:226–230Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Tollefson GD, Bosomworth JC, Heiligenstein JH, Potvin JH, Holman SL: A double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of fluoxetine in geriatric patients with major depression. Int Psychogeriatr 1995; 7:89–104Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Hamilton M: The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 1959; 32:50–55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 218–222Google Scholar

14. Norcross JC, Guadagnoli E, Prochaska JO: Factor structure of the Profile of Mood States. J Clin Psychol 1984; 40:1270–1277Google Scholar

15. Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R: Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull 1993; 29:321–326Medline, Google Scholar

16. Wechsler D: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised Manual. New York, Psychological Corp, 1991Google Scholar

17. Buschke H, Fuld PA: Evaluating storage, retention, and recall in disordered memory and learning. Neurology 1974; 24:1019–1025Google Scholar

18. McCarthy M, Ferris S, Clark E, Crook T: Acquisition and retention of categorized material in normal aging and senile dementia. Exp Aging Res 1981; 7:127–135Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Tremaine LM, Joerg EA: Automated gas chromatographic-electron-capture assay for the selective serotonin uptake blocker sertraline. J Chromatogr 1989; 496:423–429Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Dhar AK, Kutt H: An improved gas-liquid chromatographic procedure for the determination of amitriptyline and nortriptyline levels in plasma using nitrogen-sensitive detectors. Ther Drug Monit 1979; 1:209–216Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Akaike H: Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika 1987; 52:317–332Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Kaplan EL, Meier P: Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Statistical Assoc 1958; 53:457–481Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Feighner JP, Cohn JB: Double-blind comparative trials of fluoxetine and doxepin in geriatric patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1985; 46:20–25Medline, Google Scholar

24. Altamura AC, De Novellis F, Guercetti G, Invernizzi G, Percudani M, Montgomery SA: Fluoxetine compared with amitriptyline in elderly depression: a controlled clinical trial. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res 1989; 9:391–396Medline, Google Scholar

25. Fairweather DB, Kerr JS, Harrison DA: A double-blind comparison of the effects of fluoxetine and amitriptyline on cognitive function in elderly depressed patients. Hum Psychopharmacol 1993; 8:41–47Crossref, Google Scholar

26. Guillibert E, Pelicier Y, Archambault JC: A double-blind multicenter study of paroxetine vs clomipramine in depressed elderly patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1989; 350:132–134Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Dunner DL, Cohn JB, Walshe T III, Cohn CK, Feighner JP, Fieve RR, Halikas JP, Hartford JT, Hearst ED, Settle EC Jr, Menolascino FJ, Muller DJ: Two combined multicenter double-blind studies of paroxetine and doxepin in geriatric patients with major depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1992; 53(suppl 2):57–60Google Scholar

28. Hutchinson DR, Tong S, Moon CA, Vince M, Clarke A: Paroxetine in the treatment of elderly depressed patients in general practice: a double-blind comparison with amitriptyline. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1992; 6(suppl 4):43–51Google Scholar

29. Pelicier Y, Schaeffer P: A multi-center, blind study to compare the efficacy and tolerability of paroxetine and clomipramine in elderly patients with reactive depression. Encephale 1993; 19:257–261Medline, Google Scholar

30. Geretsegger C, Stuppaeck CH, Mair M: Multicenter double-blind study of paroxetine and amitriptyline in elderly depressed inpatients. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995; 119:277–281Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Salzman C: Pharmacological treatment of depression in elderly patients, in Diagnosis and Treatment of Depression in Late Life: Results of the NIH Consensus Development Conference. Edited by Schneider LS, Reynolds CF III, Lebowitz BD, Friedhoff AJ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994, pp 181–244Google Scholar

32. Young RC, Mattis S, Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Shindledecer R, Dahr AK: Verbal memory and plasma drug concentrations in elderly depressives treated with nortriptyline. Psychopharmacol Bull 1991; 27:291–294Medline, Google Scholar

33. Weingartner H, Cohen RM, Murphy DL, Martello J, Gerdt C: Cognitive processes in depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:42–47Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. King DA, Caine ED, Conwell Y, Cox C: The neuropsychology of depression in the elderly: a comparative study of normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1991; 3:163–168Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. King DA, Caine ED, Cox C: Predicting severity of depression in the elderly at 6 month follow-up: a neuropsychological study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1991; 3:64–67Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Pollock BG, Mulsant BH, Nebes R, Kirshner MA, Begley AE, Mazumdar S, Reynolds CF III: Serum anticholinergicity in elderly depressed patients treated with paroxetine or nortriptyline. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1110–1112Google Scholar

37. Gurland BJ: The range of quality of life: relevance to the treatment of depression in the elderly, in Diagnosis and Treatment of Depression in Late Life: Results of the NIH Consensus Development Conference. Edited by Schneider LS, Reynolds CF III, Lebowitz BD, Friedhoff AJ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994, pp 61–80Google Scholar