Genetic Structure of Reciprocal Social Behavior

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study examined the genetic structure of deficits in reciprocal social behavior in an epidemiologic sample of male twins. METHOD: Parents of 232 pairs of 7–15-year-old male twins completed the Social Reciprocity Scale to provide data on their children’s reciprocal social behavior. Scale scores were analyzed by using structural equation modeling. RESULTS: Intraclass (twin-twin) correlations for scores on the Social Reciprocity Scale were 0.73 for monozygotic twins (N=98 pairs) and 0.37 for dizygotic twins (N=134 pairs). The best fitting model of causal influences on reciprocal social behavior incorporated additive genetic influences and unique environmental influences. CONCLUSIONS: For school-age boys in the general population, reciprocal social behavior is highly heritable, with a genetic structure similar to that reported for autism in clinical samples. Continuous measures of reciprocal social behavior may be useful for characterizing the broader autism phenotype and may enhance the statistical power of genetic studies of autism.

Previous twin and family studies of autism have shown that the disorder is strongly genetically determined (1). By definition, autism is characterized by deficits in reciprocal social behavior, with accompanying delays in the development of language, and by the emergence of stereotypic patterns of odd behavior or behavior that reflects a restricted range of interests. Reciprocal social behavior refers to the extent to which a child engages in emotionally appropriate turn-taking social interaction with others.

Recent studies have strongly suggested that autistic symptoms are continuously distributed in the population (2, 3); the spectrum of deficits has been previously referred to as the “broader autism phenotype.” Social deficits that are below the threshold for the full diagnosis of autism aggregate significantly in family members of autistic probands (1, 3) and are therefore believed to be genetically influenced.

Previous genetic studies of such subthreshold deficits have exclusively utilized small clinical samples (families of autistic probands) and have relied on symptom counts or categorically defined measures of autistic symptoms. Our group (2) previously developed a parent/teacher-report measure of reciprocal social behavior called the Social Reciprocity Scale, a 65-item questionnaire that measures deficiency in reciprocal social behavior as a continuous variable. In a study of 287 school children and 158 child psychiatric patients with and without pervasive developmental disorders, social deficits ascertained on the Social Reciprocity Scale were continuously distributed within each group and were minimally correlated with IQ. High scores on the Social Reciprocity Scale correlated with clinical diagnoses of autistic-spectrum disorders but not with other child psychiatric disorders. Application of parametric and nonparametric factor analytic techniques failed to demonstrate separate categories of deficiency for impairment in reciprocal social behavior and other clusters of core autistic symptoms.

We undertook this study to determine the heritability of deficits in reciprocal social behavior as measured by the Social Reciprocity Scale in an epidemiologic sample of male twins.

Method

The Social Reciprocity Scale was mailed to the parents of 285 male twin pairs (age 7–15 years) randomly selected from the pool of active participants in the Missouri Twin Study (4). Parents of 232 twin pairs (98 monozygotic pairs and 134 dizygotic pairs) completed and returned the questionnaire (81.4% response rate).

The Social Reciprocity Scale is a 65-item questionnaire whose psychometric properties were tested in a study involving 445 children age 4–14 years (2). The Social Reciprocity Scale generates a summary score that serves as an index of severity along the continuum of deficits in reciprocal social behavior in the population. In the present twin sample, means and variances for Social Reciprocity Scale scores were in keeping with previously published means and variances for this age group (2). Seven subjects had Social Reciprocity Scale scores at or above the previously published mean (mean=101.5 [SD=23.6]) for subjects with pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (2).

To examine the extent to which the Social Reciprocity Scale data fit specific models of genetic and environmental causation, two-by-two variance-covariance matrices were constructed separately for the sample’s monozygotic and dizygotic twins; these data were then subjected to structural equation modeling by using the statistical software program Mx (5).

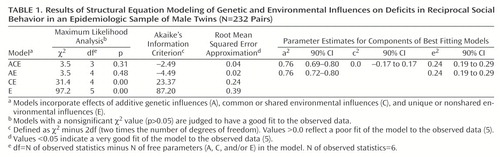

Structural equation modeling involves the use of path models that mathematically represent the totality of causal influences on a trait of interest. To quantify the degree of fit between the observed data (in this case, variance and covariance statistics for monozygotic and dizygotic twins) and values expected from a given mathematical model of causality, the maximum likelihood method is employed to generate a goodness-of-fit statistic, which follows a chi-square distribution. To be judged a good fit, models should have a nonsignificant (p>0.05) maximum likelihood chi-square. For any given model, a lower chi-square value in comparison to the chi-square value for a model with one more or one less parameter represents improved goodness-of-fit. In general, more parsimonious models (with fewer variables) are favored over more complex models if their statistics for goodness-of-fit are similar.

The first model tested (the full model) incorporated the effects of three parameters: additive genetic influences (A), common or shared environmental influences (C), and unique or nonshared environmental influences (E). The latter term (“E”) also incorporates any measurement error that exists with respect to the trait of interest. Successive models in which one or more of these variables were dropped from the full model were then tested to quantify the extent to which each model fit the observed data. We also tested more complex models that extended the original model by 1) incorporating data on age of the subjects, 2) including a latent variable for dominant genetic effects (epistasis), 3) including a latent variable for rater bias, and/or 4) adding paths for rater contrast effects. Finally, for the best fitting model(s), parameter estimates for A, C, and E were generated, with 90% confidence limits.

Results

Deficits in reciprocal social behavior were normally distributed in this epidemiologic sample of twins. For monozygotic twins (N=98 pairs; mean Social Reciprocity Scale score=34.0 [SD=20.3]), the intraclass (twin-twin) correlation was 0.73, twin A variance was 437.2, twin B variance was 388.8, and the covariance was 301.4. For dizygotic twins (N=134 pairs; mean Social Reciprocity Scale mean score=40.4 [SD=23.1]), the intraclass (twin-twin) correlation was 0.37, twin A variance was 515.2, twin B variance was 550.3, and covariance was 195.5.

The results of structural equation modeling applied to these data are shown in Table 1. The best fitting model was the AE model, which incorporated additive genetic influences and unique environment influences. Goodness-of-fit indices for more complex models that incorporated age, dominant genetic effects, rater contrast, and/or rater bias were, without exception, poorer than those derived for the AE model.

Discussion

These findings indicate that for boys in the general population, deficits in reciprocal social behavior are highly heritable. The magnitude of additive genetic influences on reciprocal social behavior in this epidemiologic twin sample was very similar to what has been observed for autism itself in previous behavioral genetic studies (1). The estimation of a relatively small influence of the unique environment parameter (which incorporates measurement error) offers further support for the validity of the Social Reciprocity Scale. Future research on the genetic structure of reciprocal social behavior is warranted; such research should include female subjects, larger samples, and multiple informants. Further research is also needed to examine the relationship between deficits in reciprocal social behavior as measured by the Social Reciprocity Scale and autistic-spectrum deficits ascertained by using conventional autism rating scales.

Since deficits in reciprocal social behavior are the sine qua non of autistic spectrum disorders, and since genetic influences have been implicated in what has been referred to as the “broader autism phenotype,” studies of the causes of autism (particularly genetic linkage studies) may be greatly facilitated by measuring reciprocal social behavior as a continuous variable in families representing the entire range of deficits in the general population. The Social Reciprocity Scale may feasibly be used in large-scale genetic-epidemiologic studies and as a clinical measure of symptoms across the autistic spectrum.

|

Presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Chicago, Oct. 19–23, 1999. From the Departments of Psychiatry, Pediatrics, and Genetics, Washington University School of Medicine. Address reprint requests to Dr. Constantino, Department of Psychiatry, Campus Box 8134, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S. Euclid Ave., St. Louis, MO 63110; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a grant from the Charles A. Dana Foundation and by NIMH grant MH-52813.

1. Bailey A, LeCouteur A, Gottesman II, Bolton P, Simonoff E, Yuzda E, Rutter M: Autism as a strongly genetic disorder: evidence from a British twin study. Psychol Med 1995; 25:63–77Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Constantino JN, Przybeck T, Friesen D, Todd RD: Reciprocal social behavior in children with and without pervasive developmental disorders. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2000; 21:2–11Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Piven J, Palmer P, Jacobi D, Childress D, Arndt S: Broader autism phenotype: evidence from a family history study of multiple-incidence autism families. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:185–190Link, Google Scholar

4. Hudziak JJ, Rudiger LP, Neale MC, Heath AC, Todd RD: A twin study of inattentive, aggressive and anxious/depressed behaviors. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:469–476Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Neale MC, Cardon LR: Methodology for Genetic Studies of Twins and Families. Boston, Kluwer, 1992Google Scholar