Plasma Cortisol and Progression of Dementia in Subjects With Alzheimer-Type Dementia

Abstract

Objective: Studies of subjects with dementia of the Alzheimer type have reported correlations between increases in activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and hippocampal degeneration. In this study, the authors sought to determine whether increases in plasma cortisol, a marker of HPA activity, were associated with clinical and cognitive measures of the rate of disease progression in subjects with Alzheimer-type dementia. Method: Thirty-three subjects with very mild and mild Alzheimer-type dementia and 21 subjects without dementia were assessed annually for up to 4 years with the Clinical Dementia Rating scale and a battery of neuropsychological tests. Plasma was obtained at 8 a.m. on a single day and assayed for cortisol. Rates of change over time in the clinical and cognitive measures were derived from growth curve models. Results: In the subjects with dementia, but not in those without dementia, higher plasma cortisol levels were associated with more rapidly increasing symptoms of dementia and more rapidly decreasing performance on neuropsychological tests associated with temporal lobe function. No associations were observed between plasma cortisol levels and clinical and cognitive assessments obtained at the single assessment closest in time to the plasma collection. Conclusions: Higher HPA activity, as reflected by increased plasma cortisol levels, is associated with more rapid disease progression in subjects with Alzheimer-type dementia.

Chronic psychosocial stressors trigger increases in the levels of glucocorticoid stress hormones that, in turn, have deleterious effects on the structure and function of CNS structures, especially the hippocampus (1 , 2) . For example, in rodents, atrophy of neuronal dendrites within the cornu ammonis of the hippocampus (3) and deficits in spatial memory (4) develop after chronic behavioral stress or administration of the glucocorticoid hormone corticosterone. In human subjects with chronic depression, which is frequently associated with increased activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (5) , decreases in the volume of the hippocampus have been correlated with the duration of illness (6 , 7) . The cellular mechanisms underlying the potentially neurotoxic effects of glucocorticoid hormones are under intense investigation (5) . In animals, behavioral stressors and corticosterone administration increase excitatory amino acid release (8 , 9) as well as the expression of N -methyl- d -aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptors (10) . Thus, glucocorticoid-triggered increases in excitotoxicity have been proposed as one mechanism of glucocorticoid-induced neuronal injury (5) . Also, because the hippocampus plays a central role in inhibiting the activity of the HPA axis (11) , hippocampal damage could produce a repetitive cycle of increasing HPA dysregulation and ongoing hippocampal injury (1) .

Glucocorticoid-related neuronal injury has also been proposed as a mechanism by which the CNS might be affected by “healthy” aging (1 , 12) . Age-related increases in corticosterone levels were first reported in rodents more than 25 years ago (13) and have been correlated with spatial memory deficits (14) . More recently, correlations have been reported between increased plasma cortisol levels, memory impairments, and smaller hippocampal volumes in nondemented elderly subjects (15 , 16) . Such findings should be interpreted with caution, however, since a portion of these subjects could have preclinical forms of Alzheimer’s disease (17) . Lupien et al. (18) suggested that elderly subjects could be clustered into subgroups characterized by increases, decreases, and no change in plasma cortisol levels over time. Again, a possible explanation for such findings is that the subjects in such subgroups may differ with regard to the frequency of preclinical forms of Alzheimer’s disease.

Increases in HPA axis activity have also been directly associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Increases in plasma cortisol levels have been reported in individuals with probable Alzheimer’s disease (19 , 20 – 23) but have been generally interpreted as evidence that the disease process of Alzheimer’s disease (i.e., Alzheimer’s-induced hippocampal degeneration) leads to disinhibition of the HPA axis. In line with this hypothesis, correlations have been reported between increases in HPA axis activity and dementia severity (24) or hippocampal volume loss (25 , 26) in individuals with probable Alzheimer’s disease. Finally, decreases in cortical concentrations of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and increases in CRH receptors have been reported in postmortem studies of subjects with Alzheimer’s disease (27 , 28) . However, as with the correlations between plasma cortisol and hippocampal volumes, these findings have been interpreted as evidence of the effect of the Alzheimer’s disease process on CRH expression.

The purpose of this study was to assess the relationship between plasma cortisol levels and clinical and cognitive measures of the rate of disease progression in subjects with very mild or mild dementia of the Alzheimer type. Our hypothesis was that higher levels of HPA axis activity, as reflected by higher plasma cortisol levels, would be correlated with more rapid progression of clinical and cognitive deficits in subjects with Alzheimer-type dementia. Among cognitive measures, we were most interested in the relationship between cortisol levels and measures of memory performance, because of previous reports linking increased HPA axis activity to hippocampal volume loss and dysfunction in elderly persons (5) . We also studied nondemented subjects age- and gender-matched to the demented subjects so that any normative relationships between cortisol levels and cognition could be assessed.

Method

The study subjects, all of whom lived in the community, enrolled in longitudinal studies of aging and dementia at the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant after the nature and risks of the study were explained. Each participant was assessed annually with a standard protocol (29) that included semistructured interviews with the participant and a collateral source (generally a spouse or an adult child) who was knowledgeable about the subject. The Clinical Dementia Rating scale was used as the primary method of recording the presence and severity of dementia (30) . This instrument rates the presence or absence of cognitive impairment on a 5-point scale (0, 0.5, 1, 2, or 3, indicating no impairment to severe impairment) in six domains or “boxes”: memory; orientation; judgment and problem solving; function in the community; function at home and hobbies; and personal care. An overall score is then derived from the individual ratings in the six domains according to standard scoring rules (30) , such that a score of 0 indicates no dementia and scores of 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 indicate very mild, mild, moderate, and severe dementia, respectively. Also, the individual box scores can be totaled to yield a sum-of-boxes total score (29) that ranges from 0 (no impairment in any domain) to 18 (maximal impairment in all domains). Interrater reliability for the Clinical Dementia Rating scale is high (31 , 32) . At our center, individuals with a score of 0.5 progress in a predictable manner to stages of more severe dementia, and at autopsy the large majority of such individuals have neuropathological Alzheimer’s disease (33) . Individuals with similar impairment have been considered by other investigators to have mild cognitive impairment (34) .

The subjects recruited for this study had Clinical Dementia Rating scores of 1 (mild dementia), 0.5 (very mild dementia), or 0 (no dementia) at the time of their assessment. To measure the rate of change of dementia severity in conjunction with the date of plasma sampling in each subject, all available annual Clinical Dementia Rating assessments were used from a period up to 2 years before and 2 years after the date of plasma sampling. The average number of assessments available in the subject groups was similar; for subjects with a score of 1, the mean number was 3.2 (SD=0.4), for those with a score of 0.5, the mean was 3.2 (SD=0.7), and for those with a score of 0, the mean was 2.7 (SD=0.8). Clinical Dementia Rating sum-of-boxes total scores were used as the clinical measure of dementia severity. Also, because of suggested links between hypercortisolemia and depression in the elderly (5) , symptoms of depression were assessed with the Geriatric Depression Scale at the time of the annual assessments (35) .

To measure the rate of change in cognitive function, the subjects’ performance was assessed with a comprehensive neuropsychological battery administered in conjunction with the annual assessments but independently of the protocol that yielded the Clinical Dementia Rating scale. Clinicians were unaware of the results of the neuropsychological test battery, and the psychometricians were unaware of the results of the Clinical Dementia Rating evaluation. The neuropsychological battery included measures of episodic memory, semantic memory, speeded psychomotor performance, visuospatial ability, and attention (36) . In a previous study (37) in which this battery was used to describe the pattern of cognitive deficits in 407 individuals with very mild and mild Alzheimer-type dementia (Clinical Dementia Rating scores of 0.5 and 1), a factor analysis revealed three factors that accounted for about 70% of the variance in cognitive performance. In a subset of these subjects who were later examined at autopsy (N=41), scores for the three factors were correlated with the frequency of β-amyloid plaques in three general regions of the brain (temporal lobe, parietal lobe, and frontal lobe). Hence, the three factor scores were named according to these brain regions: temporal factor, parietal factor, and frontal factor, respectively. In the present study, these three factor scores were calculated for each subject using weightings derived from the prior factor analyses on the subjects with very mild and mild Alzheimer-type dementia (37) .

Apolipoprotein E (apoE) gene allele status was also determined in all subjects; three (5.6%) subjects had two apoE4 alleles, 18 (33.3%) had one apoE4 allele, and 33 (61.1%) had no apoE4 alleles.

Cortisol levels were determined from plasma samples collected in conjunction with a study of CSF biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease conducted by two of the authors (A.M.F. and D.M.H.). Samples were collected by venipuncture between 7:45 a.m. and 8:00 a.m. onto ice after an overnight fast; plasma was prepared and then stored at –80°C until the time of assay. Cortisol concentrations were assayed in duplicate using a commercially available double-antibody radioimmunoassay (Clinical Assays, DiaSorin, Stillwater, Minn.). Mean values were used for all analyses. The interassay coefficient of variation of this assay is less than 15% at cortisol concentrations between 3 and 40 μg/ml, and the limit of detection is 1 μg/ml.

Statistical analyses to test for an association between the rate of change of sum-of-boxes total scores and neuropsychological battery factor scores and plasma cortisol concentrations were performed using general linear mixed models. Random coefficients models were constructed (38) , which assumed a linear growth over time for each subject in Clinical Dementia Rating total scores and the three neuropsychological battery factor scores; the models also assumed an unstructured covariance matrix between the intercept and the slope across subjects within the three dementia severity groups. We assumed that the slope over time was a linear function of cortisol levels, allowing us to assess the association between the longitudinal rate of change of the sum-of-boxes total scores and neuropsychological battery factor scores and plasma cortisol levels. This assumption was justified because no higher-order term provided a significant effect in any of the models used in the analyses. In all t or F values from these models, Satterthwaite’s approximation was used to adjust the degrees of freedom for the denominator (39) . The SAS PROC MIXED function (40) was used to implement all these models.

Results

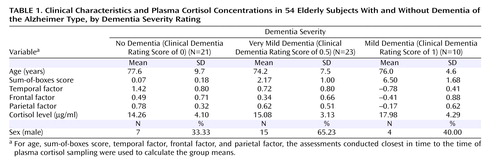

The clinical characteristics, sum-of-boxes scores, neuropsychological battery factor scores, and plasma cortisol levels for the three dementia severity groups are summarized in Table 1 . One-way analysis of variance suggested a nonsignificant trend toward a group effect for plasma cortisol levels (F=2.3, df=2, 51, p=0.092); post hoc comparisons (least squared means) of the mean plasma cortisol levels across groups suggested that subjects with a score of 1 had slightly higher plasma cortisol levels than those with scores of 0 (p=0.013) and 0.5 (p=0.046) and also that these latter groups had similar plasma cortisol levels.

When the two groups with dementia were combined (N=33), a significant positive association was observed between plasma cortisol level and the rate of increase in sum-of-boxes scores (indicating worsening of symptoms) (t=2.86, df=40, p=0.007). There was also a significant negative association between plasma cortisol level and the rate of decrease in temporal factor scores (again indicating worsening of symptoms) (t=–2.59, df=33, p=0.014) but no association with the rates of change in parietal or frontal factor scores (see Figure 1 ).

a Relationships between plasma cortisol concentrations and measures of disease progression were examined in a combined group of subjects with very mild (Clinical Dementia Rating score=0.5) and mild (Clinical Dementia Rating score=1) dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. The scatterplot in the upper panel shows the association between cortisol concentration and rate of change (slope) in sum-of-boxes score. The scatterplot in the lower panel shows the association between 8 a.m. plasma cortisol concentration and rate of change in temporal factor score. Rates of change in sum-of-boxes scores were generated with general linear mixed models and up to four annual assessments.

The magnitude of these associations was substantial: for an increase of 1 μg/ml in plasma cortisol, the annual rate of change in sum-of-boxes scores increased by 0.150 (SE=0.052), or 19% of the observed rate of change in sum-of-boxes scores (0.80 [SE=0.190]), and the annual rate of change in temporal factor scores decreased by 0.025 (SE=0.010), or 16% of the observed rate of change in temporal factor scores (–0.16 [SE=0.040]). In contrast, there were no significant associations between plasma cortisol levels and sum-of-boxes scores or temporal factor scores obtained from the assessment closest in time to the collection of the cortisol sample in the combined group of subjects with dementia.

When the subjects with very mild dementia (N=23) were evaluated separately, significant associations were observed between plasma cortisol levels and the rates of change in sum-of-boxes scores (t=2.53, df=31, p=0.017) and temporal factor scores (t=–2.58, df=26, p=0.016) but not parietal factor scores or frontal factor scores. However, when the subjects with mild dementia (N=10) were evaluated separately, there were no significant associations between plasma cortisol levels and the rates of change in sum-of-boxes scores, temporal factor scores, parietal factor scores, or frontal factor scores.

In the nondemented subjects (N=21), there were no significant associations between plasma cortisol levels and the rates of change in sum-of-boxes scores, temporal factor scores, parietal factor scores, or frontal factor scores.

When apoE allelic status was taken into consideration, the positive association between plasma cortisol levels and the rate of change in sum-of-boxes scores in demented subjects with no apoE4 alleles remained significant (t=2.76, df=41, p=0.009), but not in demented subjects with at least one apoE4 allele. The data also suggested a nonsignificant association between higher plasma cortisol levels and a more negative rate of change in temporal factor scores in demented subjects with at least one apoE4 allele (t=–1.94, df=25, p=0.063), but not in demented subjects with no apoE4 alleles. There were no significant associations between plasma cortisol levels and sum-of-boxes scores or temporal factor scores in nondemented subjects regardless of their apoE status.

There was no significant difference between groups in mean scores on the Geriatric Depression Scale obtained from the assessment closest in time to the collection of the plasma cortisol sample. There was also no significant correlation, for any group, between plasma cortisol levels and Geriatric Depression Scale scores obtained during the assessment closest in time to the collection of the cortisol sample.

Discussion

These results provide preliminary support for our hypothesis that increased glucocorticoid hormone levels, as reflected by morning plasma cortisol concentrations, are associated with the rate of change of both clinical and cognitive measures of dementia severity in subjects with Alzheimer-type dementia. It is especially intriguing that plasma cortisol levels were associated with the rate of change in the neuropsychological factor measure weighted toward memory function and previously found to be associated with neuropathological burden in the temporal lobe from Alzheimer’s disease (i.e., temporal factor scores) (37) . This association is consistent with previous reports of relationships between increased HPA axis activity and age-related hippocampal volume loss (5) . There have been conflicting reports about the density of glucocorticoid receptor expression in the hippocampus relative to other regions of the primate brain (41 – 43) . Nonetheless, our findings raise the possibility that increased glucocorticoid levels have a disproportionate impact on the Alzheimer’s disease process as it develops in the hippocampus and other structures of the medial temporal lobe (e.g., the entorhinal cortex) (44) .

The fact that no significant associations were observed between plasma cortisol levels and measures of dementia severity at the time of blood sampling suggests that increased cortisol levels were associated with more rapid rates of disease progression rather than the severity of disease. Taking this interpretation one step further, these results suggest that increased HPA axis activity as reflected by plasma cortisol levels may be associated with an acceleration of the Alzheimer’s disease process, rather than being the product of the degenerative effects of the disease on the hippocampus and HPA disinhibition.

We were surprised to find no associations between plasma cortisol and the rates of change in sum-of-boxes or neuropsychological factor scores in the elderly nondemented subjects. This finding is in apparent conflict with an earlier report of a correlation between plasma cortisol levels and the severity of cognitive impairment in nondemented elderly volunteers (16) . One explanation for this discrepancy might be that the age range was too limited in our small group of subjects without dementia. Also, our subjects with a score of 0 on the Clinical Dementia Rating scale were rigorously screened to exclude even very mild signs of dementia. At this writing, only three (5.6%) of these individuals have been examined at autopsy, so it is not possible to determine the frequency of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease in our nondemented subjects. We also did not find any association between the severity of depressive symptoms and plasma cortisol levels in any of the subject groups. However, potential subjects who met syndromal criteria for depression were excluded from our study.

Our findings of a relationship between plasma cortisol levels and markers of disease progression in subjects with Alzheimer-type dementia may be particularly applicable to the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Significant correlations were observed between plasma cortisol concentrations and measures of disease progression in subjects with very mild dementia (score of 0.5 on the Clinical Dementia Rating scale) but not in those with mild dementia (score of 1). While the correlations between plasma cortisol levels and markers of disease progression would have been more difficult to evaluate in the small group of subjects with mild dementia, the values of the correlations observed in this group were not even suggestive of a trend.

At present, the mechanism by which increased HPA axis activity could accelerate the Alzheimer’s disease process is unknown. Behavioral stressors and administration of glucocorticoid hormones have been reported to increase excitatory amino acid release (8 , 9) and the expression of NMDA glutamate receptors (10) in rodents. Using mice that overexpress the human form of amyloid precursor protein, we recently observed that chronic stress (in the form of isolation) accelerated the deposition of amyloid plaques as well as the appearance of deficits in learning and memory that usually accompany β-amyloid deposition (45) . Also, Harris-White and Chu (46) reported that glucocorticoid hormones may decrease the clearance of Aβ, which itself can have neurotoxic effects (47) . Alternatively, behavioral stressors could influence cognition by decreasing hippocampal neurogenesis (48) . Thus, stress-related increases in glucocorticoid levels could either directly or indirectly influence neuronal dysfunction and cognitive impairment associated with Aβ deposition.

There are some notable weaknesses in this study. First, our measure of the subjects’ stress responsivity was plasma cortisol levels at one time point on a single day. Our study was retrospective, and the only available plasma samples were collected in coordination with a study of CSF biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease, which involved obtaining blood and CSF on a single day. However, a correlation has been previously reported between 8 a.m. cortisol levels and dementia severity in subjects with Alzheimer-type dementia (24) . Also, our subjects may have had anticipatory anxiety on that day related to the lumbar puncture. Nonetheless, the associations observed between our simple measure of HPA axis activity and the rates of clinical and neuropsychological decline were substantial. Second, the samples available for this study, and especially the sample of mildly demented subjects, were small. Larger numbers of subjects with a wider range of dementia severity would have made it possible to more clearly determine whether the relationship between plasma cortisol concentrations and the rate of disease progression were specific to a particular stage of Alzheimer’s disease.

The results of this study need to be confirmed and extended by examining other measures of disease progression in larger numbers of subjects with Alzheimer-type dementia with wider ranges of dementia severity that has been assessed over longer periods. Studies of neuroanatomical markers of disease progression, such as measures of the structure of the hippocampus itself (49 , 50) , would be particularly useful. If the hypothesis that stress can increase glucocorticoid levels and accelerate the progression of Alzheimer’s disease is confirmed, it would give impetus to the development of therapeutic approaches, both pharmacological (51 , 52) and nonpharmacological (53) , to decrease stress and levels of stress-related glucocorticoid hormones.

1. Sapolsky RM: Stress, the Aging Brain, and the Mechanisms of Neuron Death. Cambridge, Mass, MIT Press, 1992Google Scholar

2. Fuchs E, Flugge G: Stress, glucocorticoids, and structural plasticity of the hippocampus. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 1998; 23:295–300Google Scholar

3. Watanabe Y, Gould E, McEwen BS: Stress induces atrophy of apical dendrites of hippocampal CA3 pyramidal neurons. Brain Res 1992; 588:341–345Google Scholar

4. Coburn-Litvak PS, Pothakos K, Tata DA, McCloskey DP, Anderson BJ: Chronic administration of corticosterone impairs spatial reference memory before spatial working memory in rats. Neurobiol Learning Mem 2003; 80:11–23Google Scholar

5. McEwen BS: The neurobiology of stress: from serendipity to clinical relevance. Brain Res 2000; 886:172–189Google Scholar

6. Sheline YI, Wang PO, Gado MH, Csernansky JG, Vannier MV: Hippocampal atrophy in recurrent major depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996; 93:3908–3913Google Scholar

7. Sheline YI, Sanghavi M, Mintun MA, Gado MH: Depression duration but not age predicts hippocampal volume loss in medically healthy women with recurrent major depression. J Neurosci 1999; 19:5034–5044Google Scholar

8. Lowy MT, Gault L, Yamamoto BK: Adrenalectomy attenuates stress-induced elevations in extracellular glutamate concentrations in the hippocampus. J Neurochem 1993; 61:1957–1960Google Scholar

9. Venero C, Borrell J: Rapid glucocorticoid effects on excitatory amino acid levels in the hippocampus: a microdialysis study in freely moving rats. Eur J Neurosci 1999; 11:2465–2473Google Scholar

10. Weiland NG, Orchinik M, Tanapat P: Chronic corticosterone treatment induces parallel changes in N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor subunit messenger RNA levels and antagonist binding sites in the hippocampus. Neuroscience 1997; 78:653–662Google Scholar

11. Jacobson L, Sapolsky R: The role of the hippocampus in feedback regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Endocrine Rev 1991; 12:118–134Google Scholar

12. Hibberd C, Yau JLW, Seckl JR: Glucocorticoids and the ageing hippocampus. J Anat 2000; 197:553–562Google Scholar

13. Landfield P, Waymire J, Lynch G: Hippocampal aging and adrenocorticoids: quantitative correlations. Science 1978; 202:1098–1102Google Scholar

14. Issa AM, Rowe W, Gauthier S, Meaney MJ: Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity in aged, cognitively impaired and cognitively unimpaired rats. J Neurosci 1990; 10:3247–3254Google Scholar

15. Lupien S, Lecours AR, Lussier I, Schwartz G, Nair NPV, Meaney MJ: Basal cortisol levels and cognitive deficits in human aging. J Neurosci 1994; 14:2893–2903Google Scholar

16. Lupien SJ, de Leon M, de Santi S, Convit A, Tarshish C, Nair NP, Thakur M, McEwen BS, Hauger RL, Meaney MJ: Cortisol levels during human aging predict hippocampal atrophy and memory deficits. Nat Neurosci 1998; 1:69–73Google Scholar

17. Price JL, Morris JC: Tangles and plaques in nondemented aging and “preclinical” Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 1999; 5:358–368Google Scholar

18. Lupien S, Lecours AR, Schwartz G, Sharma S, Hauger RL, Meaney MJ, Nair NPV: Longitudinal study of basal cortisol levels in healthy elderly subjects: evidence for subgroups. Neurobiol Aging 1996; 17:95–105Google Scholar

19. Davis KL, Davis BM, Greenwald BS, Mohs RC, Mathe AA, Johns CA, Horvath TB: Cortisol and Alzheimer’s disease, I: basal studies. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:300–305Google Scholar

20. Weiner MF, Vobach S, Olsson K, Svetlik D, Risser RC: Cortisol secretion and Alzheimer’s disease progression. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 42:1030–1038Google Scholar

21. Swanwick GRJ, Kirby M, Bruce I, Buggy F, Coen RF, Coakley D, Lawlor BA: Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: lack of association between longitudinal and cross-sectional findings. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:286–289Google Scholar

22. Umegaki H, Ikari H, Nakahata H, Endo H, Suzuki Y, Ogawa O, Nakamura A, Yamamoto T, Iguchi A: Plasma cortisol levels in elderly female subjects with Alzheimer’s disease: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Brain Res 2000; 881:241–243Google Scholar

23. Rasmussen S, Nasman B, Carlstrom K, Olsson T: Increased levels of adrenocortical and gonadal hormones in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2002; 13:74–79Google Scholar

24. Miller TP, Taylor J, Rogerson S, Mauricio M, Kennedy Q, Schatzberg A, Tinklenberg J, Yesavage J: Cognitive and noncognitive symptoms in dementia patients: relationship to cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone. Int Psychogeriatr 1998; 10:85–96Google Scholar

25. DeLeon MJ, McRae T, Tsai JR, George AE, Marcus DL, Freedman M, Wolf AP, McEwen B: Abnormal cortisol response in Alzheimer’s disease linked to hippocampal atrophy. Lancet 1988; 2:391–392Google Scholar

26. O’Brien JT, Ames D, Schweitzer I, Colman P, Desmond P, Tress B: Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging correlates of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in depression and Alzheimer’s disease. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168:679–687Google Scholar

27. Auchus AP, Green RC, Nemeroff CB: Cortical and subcortical neuropeptides in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 1994; 15:589–595Google Scholar

28. Davis KL, Mohs RC, Marin DB, Purohit DP, Perl DP, Lantz M, Austin G, Haroutunian V: Neuropeptide abnormalities in patients with early Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:981–987Google Scholar

29. Berg L, Miller JP, Storandt M, Duchek J, Morris JC, Rubin EH, Burke WJ, Coben LA: Mild senile dementia of the Alzheimer type, 2: longitudinal assessment. Ann Neurol 1988; 23:477–484Google Scholar

30. Morris JC: The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993; 43:2412–2414Google Scholar

31. Burke WJ, Miller JP, Rubin EH, Morris JC, Coben LA, Duchek J, Wittels IG, Berg L: Reliability of the Washington University Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR). Arch Neurol 1988; 45:31–42Google Scholar

32. Morris JC, Ernesto C, Schafer K, Coats M, Leon S, Sano M, Thal LJ, Woodbury P: Clinical dementia rating training and reliability in multicenter studies: the Alzheimer’s disease cooperative study experience. Neurology 1997; 48:228–236Google Scholar

33. Morris JC, Storandt M, Miller JP, McKeel DW, Price JL, Rubin EH, Berg L: Mild cognitive impairment represents early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol 2001; 58:397–405Google Scholar

34. Grundman M, Petersen RC, Ferris SH, Thomas RG, Aisen PS, Bennett DA, Foster NL, Jack CR Jr, Galasko DR, Doody R, Kaye J, Sano M, Mohs R, Gauthier S, Kim HT, Jin S, Schultz AN, Schafer K, Mulnard R, van Dyck CH, Mintzer J, Zamrini EY, Cahn-Weiner D, Thal J: Mild cognitive impairment can be distinguished from Alzheimer disease and normal aging for clinical trials. Arch Neurol 2004; 61:59–66Google Scholar

35. Yesavage J, Brink T, Rose R, Lum O: Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 1983; 17:37–49Google Scholar

36. Storandt M, Grant EA, Miller JP, Morris JC: Rates of progression in mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 2002; 59:1034–1041Google Scholar

37. Kanne SM, Balota DA, Storandt M, McKeel DW, Morris JC: Relating anatomy to function in Alzheimer’s disease: neuropsychological profiles predict regional neuropathology 5 years later. Neurology 1998; 50:979–985Google Scholar

38. Laird NM, Ware JH: Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics 1982; 38:963–974Google Scholar

39. Giesbrecht FG, Burns JC: Two-stage analysis based on a mixed model: large sample asymptotic theory and small sample simulation results. Biometrics 1985; 41:477–486Google Scholar

40. Littell R, Milliken GA, Stroup W, Wolfinger R: SAS System for Mixed Models. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, Inc, 1996Google Scholar

41. Patel PD, Lopez JF, Lyons DM, Burke S, Wallace M, Schatzberg AF: Glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptor mRNA expression in squirrel monkey brain. J Psychiatr Res 2000; 34:383–392Google Scholar

42. Sanchez MM, Young LJ, Plotsky PM, Insel TR: Distribution of corticosteroid receptors in the rhesus brain: relative absence of glucocorticoid receptors in the hippocampal formation. J Neurosci 2000; 20:4657–4668Google Scholar

43. Pryce CR, Feldon J, Fuchs E, Knuesel I, Oertle T, Sengstag C, Spengler M, Weber E, Weston A, Jongen-Relo A: Postnatal ontogeny of hippocampal expression of the mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors in the common marmoset monkey. Eur J Neurosci 2005; 21:1521–1535Google Scholar

44. Arnold SE, Hyman BT, Flory J, Damasio AR, Van Hoesen, GW: The topological and neuroanatomical distribution of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques in the cerebral cortex of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Cerebral Cortex 1991; 1:103–116Google Scholar

45. Dong H, Goico B, Martin M, Csernansky CA, Bertchume A, Csernansky JG: Modulation of hippocampal cell proliferation, memory, and amyloid plaque deposition in APPsw (Tg2576) mutant mice by isolation stress. Neuroscience 2004; 127:601–609Google Scholar

46. Harris-White ME, Chu T: Estrogen (E2) and glucocorticoid (Gc) effects on microglia and Aβ clearance in vitro and in vivo. Neurochem Int 2001; 39:435–448Google Scholar

47. Miguel-Hidalgo JJ, Alvarez XA, Cacabelos R, Quack G: Neuroprotection by memantine against neurodegeneration induced by β-amyloid (1–40). Brain Res 2002; 958:210–221Google Scholar

48. Malberg JE, Duman RS: Cell proliferation in adult hippocampus is decreased by inescapable stress: reversal by fluoxetine treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003; 28:1562–1571Google Scholar

49. Jack CR, Petersen RC, Xu Y, O’Brien PC, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E: Rate of medial temporal lobe atrophy in typical aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1998; 51:993–999Google Scholar

50. Wang L, Swank J, Glick IE, Gado MH, Miller MI, Morris JC, Csernansky JG: Changes in hippocampal volume and shape across time distinguish dementia of the Alzheimer type from healthy aging. Neuroimage 2003; 20:667–682Google Scholar

51. Pomara N, Doraiswamy PM, Tun H, Ferris S: Mifepristone (RU 486) for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 2002; 58:1436Google Scholar

52. Belanoff JK, Jurik J, Schatzberg LD, DeBattista C, Schatzberg AF: Slowing the progression of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease using mifepristone. Mol Neurosci 2002; 19:201–206Google Scholar

53. Fratiglioni L, Paillard-Borg S, Winblad B: An active and socially integrated lifestyle in late life might protect against dementia. Lancet Neurol 2004; 3:343–353Google Scholar