Rehospitalization Rates of Patients Recently Discharged on a Regimen of Risperidone or Clozapine

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to examine rehospitalization rates of people receiving risperidone or clozapine who had been discharged from state psychiatric hospitals in Maryland. METHOD: Rehospitalization status was monitored for all patients discharged from state psychiatric facilities on a regimen of either risperidone or clozapine between March 14, 1994, and Dec. 31, 1995. Patients were followed up with respect to readmission until Dec. 31, 1996. Time to readmission was measured by the product-limit (Kaplan-Meier) formula. Risk factors associated with rehospitalization were examined. RESULTS: One hundred sixty patients were discharged on risperidone, 75 having the diagnosis of schizophrenia. The patients with schizophrenia were more likely to be readmitted than the 85 patients with other mental disorders. Recidivism rates for schizophrenic patients discharged on risperidone versus those discharged on clozapine were not significantly different over the 24-month study period. However, no patient who received clozapine and remained discharged for more than 10 months (N=49) was readmitted, while the readmission rate for risperidone-treated patients appeared to be steady up to 24 months. At 24 months 87% of the clozapine-treated patients and 66% of the risperidone-treated patients remained in the community. No clinical or demographic variables were found to predict rehospitalization. CONCLUSIONS: This study demonstrates that the rehospitalization rates of patients taking the second-generation antipsychotics risperidone and clozapine are lower than those in previously published reports of conventional antipsychotic treatment.

Long-term outcomes for many people with schizophrenia remain disappointing. Approximately 10% of individuals with schizophrenia are at risk for suicide, and fewer than 20% will be employed in competitive work at any time (1, 2). Preventing relapse is critical to improving all areas of long-term outcome. Without effective maintenance therapy and with the occurrence of high relapse rates, improvement in patients’ functioning and quality of life will not be accomplished.

Up to one-half of all stabilized patients may be readmitted to the hospital within 1 year after discharge (3). It has been reported that the more relapses and periods off medication, the poorer the prognosis and long-term outcome for schizophrenic patients (4). Noncompliance with medication is one of the most important factors leading to relapse in schizophrenia (3, 5–7). In the outpatient setting, noncompliance rates of patients with schizophrenia are as high as 50% (8). This may be due to illness-related issues such as lack of insight, treatment management issues such as inadequate support, or drug-related issues such as intolerable side effects. Extrapyramidal side effects, including dystonic reactions, akathisia, and persistent pseudoparkinsonism, which are mediated through antagonism of dopamine D2 receptors in the basal ganglia and nigrostriatal dopamine pathways, may explain why some patients stop taking antipsychotic medication once they are discharged from the hospital (9). Second-generation antipsychotics such as clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine are associated with much better side effect profiles as compared with traditional agents (10). Thus, novel agents theoretically may increase patient compliance because of a better risk-benefit profile with respect to adverse effects and clinical efficacy. However, to date there have been no definitive studies evaluating medication compliance that have compared second-generation antipsychotics.

Relapse is a relative term in the course of schizophrenia. Outcomes such as violence, suicidal behavior, extreme psychotic behavior, and recidivism have all been used to define relapse. Determining the rate of recidivism has been one of the most systematically used methods of measuring relapse. This is usually accomplished by assessing the rehospitalization status of recently discharged patients receiving antipsychotic medications. Treatment with conventional antipsychotics has been found to be associated with 1-year recidivism rates around 30%–50% (11, 12). Hogarty (11) reported 1- and 2-year rehospitalization rates of 37% and 55%, respectively, with conventional antipsychotic treatment. Similarly, Essock et al. (13) found a 30% rehospitalization rate during the first year after discharge for patients receiving routine care with conventional antipsychotics. Weiden and Olfson (12) analyzed all published reports of rehospitalization and estimated by survival curve analysis that in the “real world,” 50% of patients treated with conventional antipsychotics will be readmitted within 1 year, and about 80% of patients at 2 years. These rates may be decreased with the combination of depot neuroleptics and intense therapy. Hogarty found that fluphenazine decanoate in combination with social therapy lowered relapse rates to about 23% per year. Schooler et al. (9) reported that fluphenazine decanoate therapy in combination with intense applied family management was associated with a 19% rehospitalization rate over a 2-year period. Although these results under optimal conditions are much better, the actual “real-world use” of treatment with therapeutic doses of depot medications is probably associated with a higher rate of recidivism.

There is good evidence that the novel antipsychotics are more protective against relapse than the traditional antipsychotics. Essock et al. (13) compared 1-year rehospitalization rates of treatment-resistant patients randomly assigned to clozapine or standard treatment. Patients discharged on clozapine were less likely to be readmitted (18%) than those receiving conventional therapy (30%). It was also noted that the amount of contact hours did not differ between the groups, leading to the conclusion that visits for drawing blood samples did not explain the lower recidivism rate. Honingfeld and Patin (14) reported that 2-year rehospitalization rates were 28% for patients receiving clozapine and 56% for those receiving conventional antipsychotic therapy. Satterlee et al. (unpublished data, 1996) reported 1-year rehospitalization rates as 19% for patients taking olanzapine and 28% for those receiving conventional antipsychotic treatment. Although there are no prospective studies examining recidivism rates among patients taking risperidone, there are retrospective studies which suggest that similar decreases in rehospitalization rates may be seen with this agent (15). It appears that the novel antipsychotics may be associated with lower relapse and rehospitalization rates than conventional antipsychotics. Therefore, it is important to evaluate and compare rehospitalization rates for the antipsychotics under real-world use conditions.

This study examined rehospitalization rates of people receiving risperidone and clozapine who had been discharged from state psychiatric hospitals in Maryland. In addition, we evaluated predictors of outcomes and identified risk factors associated with relapse.

METHOD

The study was designed to evaluate prospectively the effect of the introduction of novel antipsychotics on patient hospitalization status in the state of Maryland’s inpatient facilities. Records of inpatients in Maryland’s psychiatric hospitals were eligible for the study. In accordance with federal regulations, this protocol was reviewed by the University of Maryland institutional review board and judged to be exempt from the requirement of written informed consent. The database for antipsychotics consists of six major public psychiatric facilities located throughout the state, accounting for 92% of the beds (N=2,024 of 2,205) in the State of Maryland Outcomes Monitoring Program. These facilities contain a group of patients from diverse ethnic backgrounds and geographical locations. All patients who were successfully discharged on a regimen of either risperidone or clozapine between March 14, 1994 (the date risperidone was first prescribed in our system), and Dec. 31, 1995, were included in the study. A successful discharge was defined as a patient who was started on risperidone or clozapine treatment and discharged on that same drug within one admission. After discharge, all patients were followed by their routine care providers, mostly in community mental health centers around the state of Maryland. No special care or therapy was provided for the two patient groups, and no patients were involved in the patient-to-patient program (an outpatient direct telephone assistance program provided by Janssen Pharmaceutica for patients receiving risperidone). Readmission was defined as rehospitalization in any public hospital for a psychiatric condition. All patients were followed for possible readmission until Dec. 31, 1996. In this study, those who were rehospitalized in a private facility would not be identified as having been readmitted. However, this type of readmission would have been very rare; private readmissions were less than 2% of all readmissions from this group in prior analyses. To classify appropriate diagnoses, chart reviews were done by two members of the research team to verify the most recent diagnoses with computerized records.

The rehospitalization status of the patients discharged on risperidone and on clozapine was monitored from March 14, 1994, to Dec. 31, 1996. The risk factors for readmission that were examined among the risperidone patients were diagnosis, dose, sex, and age. For clozapine patients they were sex, age, and race. All of the clozapine patients had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Data on race were not available for the risperidone-treated patients. Recidivism rates of the risperidone patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia were compared with those of the clozapine patients.

To measure time to readmission, we used survival analysis. Survival curves were estimated by the product-limit (Kaplan-Meier) formula. The significance of differences between the clozapine and risperidone groups was measured by the Mantel-Cox chi-square test. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to analyze continuous covariates and those thought to have an impact on time to readmission, such as age, race, and sex. Standard chi-square tests, paired and unpaired t tests, and nonparametric tests were used to compare demographic variables. All tests were two-tailed, and significance was defined as an alpha less than 0.05.

RESULTS

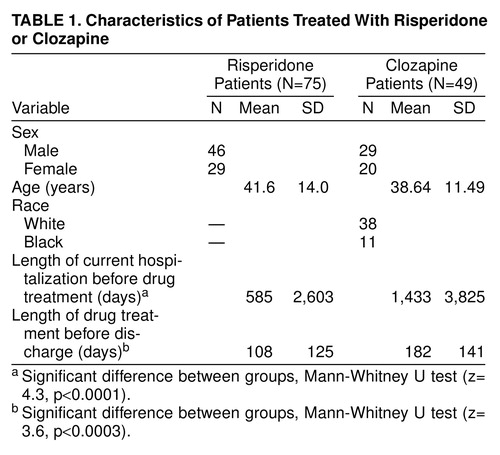

During the observation period of this study, 179 schizophrenic patients were started on clozapine in Maryland inpatient facilities. Of these patients, 49 (27%) were discharged. These patients were compared with the group of schizophrenic patients discharged on risperidone. Of the 609 patients started on risperidone during the observation period, 315 (52%) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Seventy-five (24%) of these 315 schizophrenic patients were discharged during the study period, a discharge rate not significantly different from that for the clozapine patients. Characteristics of both groups are listed in Table 1.

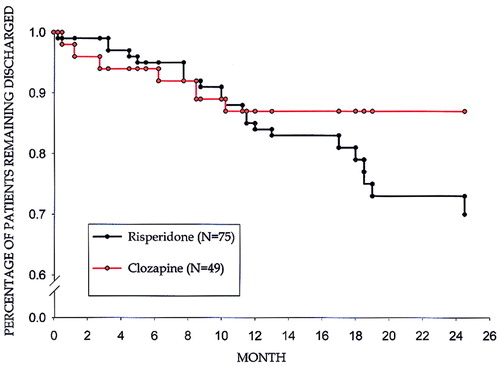

The mean time to readmission for the patients receiving risperidone was 360 days (SD=213, range=2–748), and the median time was 319 days (95% confidence interval [CI]=223–514). The mean length of discharge time for clozapine patients who were readmitted was 137 days (SD=113, range=11–281), and the median was 132 days (95% CI=11–281). The mean length of follow-up for patients who were not readmitted was 612 days (SD=159) for the risperidone group and 559 days (SD=221) for the clozapine group. The percentage of schizophrenic patients remaining discharged was 83% (95% CI=75%–91%) at 12 months and 66% (95% CI=52%–80%) at 24 months for those receiving risperidone. For the clozapine patients, the percentage remaining discharged was 87% (95% CI=77%–97%) at 12 months and remained constant at 24 months. Thus, the rate of readmission for the clozapine group was 13% (95% CI=3%–23%) at both 1 and 2 years, compared with the risperidone group’s rates of 17% (95% CI=9%–25%) and 34% (95% CI=20%–48%), respectively. There were no significant differences in readmission rates between the patients receiving risperidone and those receiving clozapine (Figure 1).

In the first 10 months of follow-up, the rates of readmission were similar for risperidone and clozapine patients: 12% (N=9) of the 75 risperidone patients and 12% (N=6) of the 49 clozapine patients were readmitted. However, an additional 12 (16%) of the risperidone patients were readmitted in the period from 11 to 24 months, whereas no additional clozapine patients were rehospitalized after 10 months.

Age, sex, and race did not contribute to the risk of readmission for patients taking clozapine. Length of hospitalization before the start of medication and length of time from the start of medication to discharge also did not contribute to the readmission risk in either group of patients.

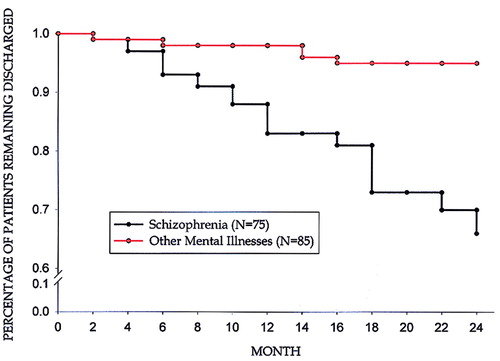

The total patient database from which rehospitalization data for risperidone were extracted consisted of 609 patients who began taking risperidone between March 14, 1994, and Dec. 31, 1995. One hundred sixty patients were discharged on risperidone during the observation period, 26% of the total number who started the drug. The patients with schizophrenia constituted the largest proportion of users of risperidone (47%, N=75) among the 160 discharged during this period. Other patients discharged on risperidone had diagnoses of depression (14%, N=22), schizoaffective disorder (13%, N=21), bipolar disorder (13%, N=21), disorders of childhood (3%, N=5), substance abuse (1%, N=2), and other diagnoses (9%, N=14).

Of the group receiving risperidone, significantly more of the 85 patients with a nonschizophrenic diagnosis remained discharged than of the 75 patients with schizophrenia. As mentioned, the percentage of schizophrenic patients remaining discharged was 83% at 12 months and 66% at 24 months. For all other mental disorders, the percentage of patients remaining discharged while taking risperidone was 98% (95% CI=92%–99%) at 12 months and 95% (95% CI=87%–98%) at 24 months (Figure 2). In complementary fashion, the rates of readmission at 12 and 24 months were 17% (95% CI=9%–25%) and 34% (95% CI=20%–48%), respectively, for those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and 2% (95% CI=0%–6%) and 5% (95% CI=1%–9%), respectively, for those with all other diagnoses combined. No significant factors (such as age, sex, or dose) were found to be related to the risk of readmission in either of these diagnostically different groups receiving risperidone. The mean risperidone doses for the schizophrenic patients and nonschizophrenic patients were 5.6 mg/day (SD=3.2) and 4.5 mg/day (SD=2.7), respectively (t=2.36, df=157, p<0.02). Further, doses of risperidone (≤6 mg/day versus >6 mg/day) were examined by survival curve analysis for rehospitalization risk and were not found to contribute to that risk (Mantel-Cox χ2=0.09, df=1, p=0.76). Doses were analyzed within each diagnosis as well and were not found to be a risk factor for rehospitalization.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare patients taking two atypical antipsychotics with respect to rehospitalization rates and the first to evaluate the risk of rehospitalization for patients taking risperidone. Both risperidone and clozapine may be associated with recidivism rates that are lower than those in published reports on conventional antipsychotic agents. The outcome data for conventional neuroleptics reported by Hogarty (11) probably represent the rates of rehospitalization that would be expected with unselected conventional therapy and usual supportive care. These recidivism rates of 37% at 12 months and 55% at 24 months are much higher than those we found in both our risperidone- and clozapine-treated groups. In a recent nationwide study of patients treated with standard doses of fluphenazine decanoate plus either supportive or intensive applied family therapy, Schooler et al. (9) reported that 19%–31% of the patients relapsed over a 2-year period. This is a less favorable outcome than was found with clozapine treatment (13%) in the present study and is similar to the rate with risperidone (34%) at 24 months.

Although only data on patients who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia were available for the group receiving clozapine, among the patients receiving risperidone, patients with other diagnoses were compared with those who had schizophrenia. We found that patients with nonschizophrenic diagnoses who were treated with risperidone were significantly less likely to be rehospitalized than those who suffered from schizophrenia. This may be related to the findings that the rate of response to risperidone may be higher in patients treated with risperidone who suffer from bipolar or schizoaffective disorder compared with those who have schizophrenia (16). Also, although dosage did not contribute to the risk of relapse, patients with other diagnoses were taking a significantly lower dose of risperidone than those with schizophrenia. We know that risperidone is associated with dose-related extrapyramidal side effects(17). Thus, it is possible that higher doses may be associated with higher rates of noncompliance with medication, and therefore, patients prescribed higher doses may secondarily have higher rates of relapse. Finally, the intrinsic risk of relapse may be different between these diagnostic groups.

Demographic and clinical variables were not found to contribute significantly to the risk of relapse in either treatment group. Other studies have identified variables that are correlated with relapse in patients taking antipsychotic medications; noncompliance with medication, substance abuse, a history of frequent hospitalizations, and dissatisfaction with family relations have all been reported (5, 6, 18). Demographic variables, the extent of outpatient services, access to care, quality of life, and case management have all been found not to be related to relapse (6, 18, 19). We were able to examine sex, age, race (clozapine group only), dose (risperidone group only), diagnosis (risperidone group only), length of hospitalization before the start of medication, and length of time from the start of medication to discharge. Hospitalization history, age at onset of illness, substance abuse history, and outpatient follow-up information were not available for analysis. However, as in previous reports on patients receiving typical antipsychotics, basic demographic variables were not related to the risk of being readmitted.

We found that the rate of rehospitalization for patients taking risperidone doubled during the second year after discharge (from 17% to 34%) yet remained constant for patients taking clozapine (13%). This suggests that patients discharged on clozapine who relapse are most likely to relapse earlier than patients treated with risperidone. All rehospitalizations for patients on clozapine in our study were within the first 10 months. If a patient on clozapine is beyond those first 10 months after discharge, the patient has a very high likelihood of remaining in the community.

Although clozapine was associated with a lower risk of rehospitalization at both 1 and 2 years, the mean time to rehospitalization was earlier. For the patients discharged and readmitted on clozapine, the mean time in the community was 137 days, whereas it was 360 days for patients on risperidone. Further, the mean length of time of medication treatment before discharge was significantly longer for the patients discharged on clozapine (182 versus 108 days). Thus, the clozapine patients may have had a greater opportunity to relapse while hospitalized as opposed to relapsing once they had been discharged. It is possible that the survival curve for patients discharged on risperidone would have been more similar to that of the clozapine group if drug treatment before discharge had been comparable. Determining the appropriate length of antipsychotic treatment before discharge may contribute to a lower risk of rehospitalization.

The conclusions drawn from this analysis must be tempered according to the limitations of our strategy. Patients were not randomly assigned to the two treatments, and this comparison involved clozapine, which is reserved for patients with treatment-refractory illness (or those intolerant of conventional treatment), and risperidone, which has no such limitations on its use. Therefore, it is unlikely that these patients would be directly comparable on measures of treatment response or outcome. However, no demographic or clinical variables that we examined contributed to the risk of relapse, and it would be interesting to examine dosage, side effect occurrence, and response criteria in relation to early readmission. These patients may not have been stabilized or have tolerated their medication as well as patients who remain unhospitalized.

The risk of relapse with risperidone appears to increase linearly over time, although at lower rates than with conventional agents. This suggests that there may be intrinsic differences in the relapse prevention capabilities of risperidone and the conventional medications.

Although the goals of the current study were not to evaluate the cost implications of reduced rehospitalization, the benefit of this finding should not be overlooked. Weiden and Olfson (12) estimated that the total annual cost of short-term hospital admissions for relapsing schizophrenic patients is almost $2.3 billion. As the new higher-priced antipsychotics enter the marketplace and as centers cope with increased direct drug expenditures, it is important to place long-term outcomes such as decreased hospitalizations into the overall cost equation. A multisite Department of Veterans Affairs study (20) found that overall costs for clozapine and haloperidol treatment were similar, while clozapine was found to be more effective at reducing positive symptoms. Meltzer et al. (21) reported that there was actually a decrease in total treatment costs for patients who were treated with clozapine, primarily due to a decrease in hospitalizations. Others have also reported clozapine to be cost-effective for maintenance therapy (22–26). In a study by Viale et al. (27), risperidone was found to decrease total psychiatric health care costs by 3.4% after initiation of treatment. Most other studies evaluating cost implications of risperidone involved a decrease in the current hospital stay after initiation of treatment (15, 28). Long-term comparative follow-up studies evaluating costs and readmission rates are needed for the second-generation antipsychotics (i.e., clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine).

The main limitation to the findings of this study is the lack of a conventional antipsychotic comparison group. However, because the recidivism rates for clozapine are similar to those in other published reports and risperidone appears to fall within the expected range, we have no reason to suspect that recidivism rates in Maryland’s state facilities among patients receiving conventional antipsychotics would be any different from published reports of 20%–50%. In future studies we plan to validate and analyze data on conventional antipsychotics regarding rehospitalization rates as well as prospectively monitor rehospitalization rates for patients taking olanzapine, quetiapine, and other second-generation antipsychotics within the State of Maryland Outcomes Monitoring Program.

As new antipsychotics enter the marketplace, it is important to compare the benefits of these agents with those of conventional antipsychotics. This study demonstrates that rehospitalization rates with risperidone therapy are similar to those with clozapine therapy. These rates are lower than prior published rates of recidivism with conventional antipsychotics and are similar to those of well-followed patients treated with depot conventional medication. The second-generation drugs may have a more tolerable side effect profile, leading to better patient compliance, or there may be other reasons for the lower rates we see. These findings must be interpreted within the limitations of this study design, and replication of these finding with direct comparison groups of patients treated with conventional antipsychotic agents is critical.

Received July 8, 1998; revision received Nov. 23, 1998; accepted Nov. 30, 1998. From the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, University of Maryland, Baltimore, Schools of Medicine and Pharmacy. Address reprint requests to Dr. Conley, Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, Box 21247, Baltimore, MD 21228. Supported in part by the Theodore and Vada Stanley Foundation and by NIMH grant MH-40279. The authors thank Carol Younkins and Janice Ingson-Kourkoules for contributions to data management and collection and Dr. William T. Carpenter for advice on this work.

|

FIGURE 1. Time Course to Readmission of Recently Discharged Patients Taking Risperidone or Clozapinea

aMantel-Cox χ2=2.66, df=1, p=0.10.

FIGURE 2. Time Course to Readmission of Recently Discharged Patients With Schizophrenia or Other Mental Illnesses Taking Risperidonea

aMantel-Cox χ2=15.60, df=1, p<0.0001.

1. Drake R, Gates C, Whitaker A: Suicide among schizophrenics: a review. Compr Psychiatry 1985; 26:90–100Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Lehman A: Vocational rehabilitation in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1995; 21:645–656Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Weiden P, Aquila R, Standard J: Atypical antipsychotic drugs and long-term outcome in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57:53–60Medline, Google Scholar

4. Sheitman BB, Lee H, Strauss R, Lieberman JA: The evaluation and treatment of first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull 1997; 23:653–661Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Haywood TW, Kravitz HM, Grossman LS, Cavanaugh JL Jr, Davis JM, Lewis DA: Predicting the “revolving door” phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, schizoaffective, and affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:856–861Link, Google Scholar

6. Sullivan G, Wells KB, Morgenstern H, Leake B: Identifying modifiable risk factors for rehospitalization: a case-control study of seriously mental ill persons in Mississippi. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1749–1756Google Scholar

7. Kent S, Yellowlees P: Psychiatric and social reasons for frequent rehospitalization. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1994; 45:347–350Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Gaebel W: Towards the improvement of compliance: the significance of psycho-education and new antipsychotic drugs. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 12(suppl 1):S37–S42Google Scholar

9. Schooler NR, Keith SJ, Severe JB, Matthew SM, Bellack AS, Glick ID, Hargreaves WA, Kane JM, Ninan PT, Jacobs FA, Lieberman JA, Mance R, Simpson GM, Woerner MG: Relapse and rehospitalization during maintenance treatment of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:453–463Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Miller CH, Mohr F, Umbricht D, Woerner M, Fleischnacker WW, Lieberman JA: The prevalence of acute extrapyramidal signs and symptoms in patients treated with clozapine, risperidone, and conventional antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 58:69–75Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Hogarty GE: Prevention of relapse in chronic schizophrenic patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1993; 54(March suppl):18–23Google Scholar

12. Weiden PJ, Olfson M: Cost of relapse in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1995; 21:419–429Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Essock SM, Hargreaves WA, Covell NH, Goethe J: Clozapine’s effectiveness for patients in state hospitals: results from a randomized trial. Psychopharmacol Bull 1996; 32:683–697Medline, Google Scholar

14. Honigfeld G, Patin J: A two-year clinical and economic follow-up of patients on clozapine. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990; 41:882–890Abstract, Google Scholar

15. Addington DE, Jones BJ, Bloom D, Chouinard G, Remington G, Albright P: Reduction of hospital days in chronic schizophrenic patients treated with risperidone: a retrospective study. Clin Ther 1993; 15:917–926Medline, Google Scholar

16. Keck PE Jr, Wilson DR, Strakowski SM, McElroy SL, Kizer DL, Balistreri TM, Holtman HM, DePriest M: Clinical predictors of acute risperidone response in schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and psychotic mood disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:466–470Medline, Google Scholar

17. Marder SR, Meibach RC: Risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:825–835Link, Google Scholar

18. Postrado LT, Lehman AF: Quality of life and clinical predictors of rehospitalization of persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 1995; 46:1161–1165Google Scholar

19. Rossler W, Loffler W, Fatkenheuer B, Riecher-Rossler A: Case management for schizophrenic patients at risk for rehospitalization: a case control study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1995; 246:29–36Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Rosenheck R, Cramer J, Xu W, Thomas J, Henderson W, Frisman L, Fye C, Charney D, Department of Veteran’s Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Clozapine in Refractory Schizophrenia: A comparison of clozapine and haloperidol in hospitalized patients with refractory schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:809–815Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Meltzer HY, Cola P, Way L, Thompson PA, Bastani B, Davies MA, Snitz B: Cost effectiveness in neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1630–1638Google Scholar

22. Revicki DA, Luce BR, Wechsler JM, Brown RE, Adler MA: Cost-effectiveness of clozapine for treatment-resistant schizophrenic patients. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990; 41:850–854Abstract, Google Scholar

23. Jonsson D, Walinder J: Cost-effectiveness of clozapine treatment in therapy-refractory schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1995, 92:199–201Google Scholar

24. Frank RG: Clozapine’s cost-benefits (letter). Hosp Community Psychiatry 1991; 42:92Abstract, Google Scholar

25. Goldman HH: Determining a fair price for inpatient psychiatric care. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1991; 42:139–140Abstract, Google Scholar

26. Aitchison KJ, Kerwin RW: Cost-effectiveness of clozapine: a UK clinic-based study. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 171:125–130Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Viale G, Mechling L, Maislin G, Durkin M, Engelhart L, Lawrence BJ: Impact of risperidone on the use of mental health care resources. Psychiatr Serv 1997; 48:1153–1159Google Scholar

28. Aronson SM: Cost-effectiveness and quality of life in psychosis: the pharmacoeconomics of risperidone. Clin Ther 1997; 19:139–147Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar